Looking for Limbs in all the Right Places: Retrieving the Civil War’s Broken Bodies

It was mid-May, and it was beautiful outside. I was sitting inside, however, at a table in the reading room of the Connecticut Historical Society. But I wasn’t thinking of the warm sunshine I was missing because I had just opened a manila folder and seen something amazing. It was a fragile sheet of writing paper, which had been folded many times into a tight, small square and had frayed and torn along the folds. Someone had attached the pieces back together with tape and postal seals. The reassembled image had been painted in watercolors: a close-up view of a right foot and ankle, resting against a mattress. They look young and healthy—except for the toes, which are painted a dark, angry black that creeps toward the bridge of the foot. A thin red line frames the image and in the bottom left corner the following words appear, in black script: “Gangren from frost bite” (fig. 1).

I carefully removed this image from the file and found another underneath it, in the same condition, torn and repaired. Again, a shock: a foot rests in the same manner on the mattress, but the toes are gone, replaced by ragged holes painted in vivid hues of red, blue, purple, and yellow. Bits of bone poke through the skin. Again, there is a thin red border and the script: “Gangren from frost bite” (fig. 2). A before-and-after diptych, I thought, a common visual trope in images of amputees and amputation. Then I looked more closely. The amputated toes actually belonged to the left foot, not the right. These were two different feet. Interesting.

I laid the images side-by-side and sat down to ponder them. Whose feet were they? Why one image of the right and one of the left? Had he lost all ten toes? How did he get frostbite? Who made the decision to amputate? Did the amputee himself paint these images, or did someone else? If he painted them himself, why would he do such a thing? And what were the recipients of these intently folded pages supposed to think when they opened them up? I did not—and still don’t—know the answers to most of these questions.

What I do know is that the paintings—and presumably the feet as well—belonged to James Wilbraham, a soldier who served in Company D, 16th Connecticut Volunteers. His enlistment and discharge papers, also in the file, noted that he had joined the Union army in August 1862 and had been discharged in February 1864 “by reason of loss of toes & heels from frost bite.” A gravestone at the Old St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Enfield, Connecticut, notes that Wilbraham died eight months later, cause unknown.

I came to the Connecticut Historical Society, and to James Wilbraham’s amputated toes, in pursuit of manuscript evidence for my book project, Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War. I was interested in all different kinds of ruins. The kinds you usually think of in the context of the war—city buildings, plantation houses, slave quarters—but also the ruins of living things: trees shot to pieces by shot and shell, and the bodies of men ripped apart by musket and artillery fire. Through its destruction, I believed, one could come to know the wartime experience, the real Civil War that, according to Whitman, never gets into the books.

I started my search for ruined men in manuscripts: in letters and diary entries. I read broadly through collections stored at various historical societies and libraries in New England and the South. I wasn’t necessarily interested in the most famous of war amputees—Confederate General John Bell Hood or Union General Oliver O. Howard—but in the rank and file. How were these men blown apart and why? How did soldiers and civilians react to the sudden proliferation of disarticulated bodies and veteran amputees that the Civil War created?

The letters and diaries contained an abundance of rich material regarding the effects of shot and shell on the human body. They also revealed anxious attention to amputation; soldiers and civilians expressed their fears of it and described watching the amputations of others with a mix of terror and fascination.

There was Massachusetts Captain Richard Cary, who jokingly reassured his wife that, “I told the Doctor what you said about amputation & he promised he would never cut me in half without a consultation,” and Maine private Napoleon Perkins, who wrote about the amputation of his leg with meticulous detail. He woke up twice during the surgery and talked to the surgeons about their progress, and then requested more ether. I compiled hundreds of pages of notes from such sources, from long descriptive accounts of mangled bodies on the battlefield to passing references to amputees.

Napoleon Perkins’ account of his life after amputation—he looked for work unsuccessfully for years, noting that, “The proprietors all seemed to feel sorry for me but they had no work that a one leg man could do”—interested me, as did the responses of his friends and family members to the loss of his leg.

I therefore turned my attention to postwar sources—pension applications, broadsheets that amputees published as moneymaking ventures, and pamphlets published by prosthetics manufacturers. All of these documents gave me a good sense of the valuation of veterans’ missing limbs. In the twenty years after the war ended, the U.S. government (which provided pension funds and other forms of aid only to Union veterans) put prices on absent body parts. A man’s loss of both hands, for example, was worth $25 per month in 1864; by 1875 the payment had increased to $50 per month. By 1880, Union soldiers with one empty sleeve were receiving an annual pension of $432 ($36 per month).

The federal government also established a prosthetics program for Union veterans, providing artificial arms and legs (or money to purchase them) after 1862. As a result, the prosthetics industry—which was based in New England and New York—flourished.

And as manufacturers competed for customers, they published thousands of pages explaining their inventions and providing testimonials regarding their quality. The prosthetics pamphlets I read through at the Center for the History of Medicine at Harvard Medical School suggested that not only did soldiers’ missing limbs acquire monetary value during and after the war, they also conveyed complex cultural meanings.

I came to understand that every part of these pamphlets—the introduction appealing to the patriotic spirit and manliness of Union veterans, the detailed illustrations of prosthetic designs attesting to their originality and their technological precision, and the reprinted letters raving about the “natural” feel and look of the product—shaped discussions of American manhood during and after the war. Also, prosthetics inventions and the men who wore them were seen as emblematic of the nation’s industrial “genius” but called attention to the costs of such achievements. If you couldn’t tell that a soldier was wearing a prosthetic limb, then how could you tell what was “real” what was “counterfeit” in American society?

These concerns about whole and incomplete men were also evident in American visual culture in the 1860s and ’70s. As I turned my attention to graphics, most of them held in the vast collections of the American Antiquarian Society, I found hundreds of Civil War amputees. They appeared in political cartoons, lithographs, engravings, woodcut illustrations, and the sketches and pictures that soldiers such as James Wilbraham drew themselves.

During my month of residency at the AAS as a Last Fellow in Graphic Arts, I found (among more than 300 images depicting legless and armless men) two political cartoons that demonstrate the many meanings that Civil War amputees embodied during the war.

Late in the war, a Union newspaper (probably Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun, a newspaper devoted to humorous anecdotes and cartoons, its first run in 1859) published a six-panel cartoon entitled “Rebel Bulletins Illustrated” (fig. 3). The first panel depicts a rebel soldier (“Lee’s messenger”) running toward Richmond with a banner that says “Defeat of Grant Victory No. 1.” In subsequent panels, the messenger brings news of further defeats of Grant but loses a limb or two each time. In the penultimate image, the messenger is carried by a “contraband” (a fugitive slave), while in the final panel, a different male slave holds the banner in his right hand, and in his left he holds a basket, filled with the body parts—”all that remains” of Lee’s messenger.

At first I had no idea how to interpret this set of images. Luckily for me, an astute librarian had written the date of publication on the back: July 1864. By that time Grant’s spring campaign had settled into a siege of Petersburg after seven long weeks of campaigning and six major battles. In the cartoon, the messenger’s body is intact after the first battle (the Wilderness) but with every move that Grant’s army makes to the southeast during the campaign, the southern soldier loses limbs. These corporeal losses contrast with the strident messages of the text in the banners, of victories won and “Yankees routed.” An explicit critique of the delusional self-regard and the failure of Confederate war aims by the summer of 1864—and the centrality of emancipation to the progress of the war—”Rebel Bulletins Illustrated” uses amputation and missing limbs as signs of southern military and political weakness.

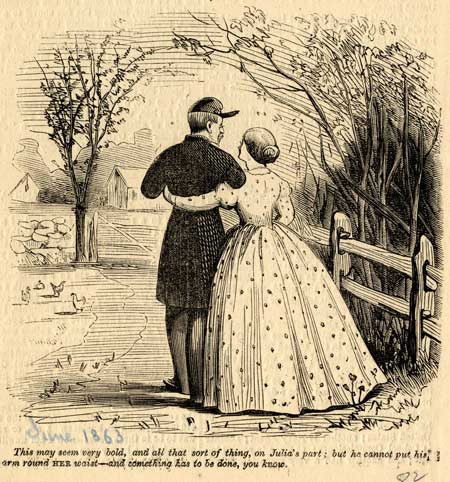

One year earlier, a cartoon appeared in another northern newspaper: a couple walks close together and away from the viewer, sauntering along a path next to a countryside fence and toward a leafy bower (fig. 4). The woman wears a plain dress with a flowery pattern and the man wears a Union uniform. She has her left arm wrapped around the man’s waist (her white, patterned dress illuminated by the dark color of his uniform) because the soldier’s arms have been amputated. The caption reads: “This may seem very bold, and all that sort of thing, on Julia’s part; but he cannot put his arm around HER waist—and something has to be done, you know.”

Because the veteran amputee can no longer make the first move, Julia has taken control of their courtship. Her boldness is required, for “something must be done, you know” to integrate amputees—who, without their limbs, were somehow less than men—back into the American family through normative heterosexual relationships. However, this reintegration has its cost; Julia’s audacity threatens to upend antebellum gender roles and provide American women with more power than many men (and women) found acceptable. Here, the figure of the veteran amputee provokes discussion about the effects of wartime violence on family relations.

Around 45,000 northern and southern men returned home from the battlefields and hospitals of the South, having given their limbs for their countries. They became primary symbols of both the positive and negative aspects of wartime violence. They also became central figures in its print, visual, and material culture: once you start looking for them, you find them everywhere.

For this I am grateful, not only because this amazing abundance of material allowed me to write a book chapter on ruined men, but also because the shock of seeing them conveys a sense of the “true” war, its material and corporeal reality. That those vivid images of James Wilbraham’s feet have come down to us in a plain manila file folder is somewhat miraculous, given that his relatives did not save much else pertaining to his life. And we should all look at those blackened and then missing toes, the flesh healing over but the bones still sticking out, to know the nature of war and its costs.

Further reading:

For details on James Wilbraham’s enlistment and discharge from the Union army, see Enlistment and Discharge Papers (1862, 1864), James Wilbraham Papers (1862-1864), Connecticut Historical Society. For Richard Cary’s and Napoleon Perkins’ thoughts on amputation see Richard Cary Letters, Massachusetts Historical Society and Perkins, “The Memoirs of N.B. Perkins,” New Hampshire Historical Society.

For further reading on the cultural significance of the broken and amputated bodies of Union and Confederate soldiers in the American Civil War, see Laurann Figg and Jane Farrell-Beck, “Amputation in the Civil War: Physical and Social Dimensions,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 48: 4 (October 1993): 454-75; Lisa Maria Herschbach, “Fragmentation and Reunion: Medicine, Memory, and Body in the American Civil War” (PhD diss., Harvard, 1997); Brian Craig Miller, “The Women who Loved (or Tried to Love) Confederate Amputees,” in Weirding the War: Tales from the Civil War’s Ragged Edges, ed. Berry (Georgia, 2011); Kathy Newman, “Wounds and Wounding in the American Civil War: A (Visual) History,” Yale Journal of Criticism6: 2 (Fall 1993): 63-85. For details regarding federal and state government aid for Union and Confederate veterans, see, for example, Jennifer Davis McDaid, “With Lame Legs and No Money: Virginia’s Disabled Confederate Veterans,” Virginia Cavalcade 47: 1 (Winter 1998): 14-25; Theda Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States(Harvard, 1992); Ansley Herring Wegner, Phantom Pain: North Carolina’s Artificial-Limbs Program for Confederate Veterans (North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2004).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.1 (October, 2011).

Megan Kate Nelson is a lecturer in history and literature at Harvard University. She is the author of Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp (2005) and the forthcoming Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (2012).