Loving the Plant That Saves You

In 1836, the French novelist X.B. Saintine (nom de plume of Joseph-Xavier Boniface) published a novel entitled Picciola about a man who falls passionately in love with a flowering plant. Translated into English in 1838, the novel became a bestseller in America almost overnight. An 1839 review in Ladies’ Companion called Picciola “the most striking and original tale that has appeared in our country for a long time” and noted that the book passed through four editions in its first month of publication. By 1847, reviews in a wide range of periodicals—from women’s magazines to agricultural journals—were already hailing it as a classic. A few decades later, the publishing house J.B. Ford anthologized Picciola among other “standard masterpieces of imaginative fiction,” alongside Robinson Crusoe, Pilgrim’s Progress, Gulliver’s Travels, Arabian Nights, and The Vicar of Wakefield, in a collection to which Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the introduction. Some of the most famous American authors of the century were fans. Stowe praised its “tenderness and sweet simplicity” and Emily Dickinson thanked her cousin for recommending the novel. Its appeal also seems to have been long-lasting: Marcel Proust likewise counted Picciola among his favorite books.

The story of a man’s love for a plant may be unusual, but the narrative foundation is entirely conventional. The protagonist is an aristocrat, Count Charles Veramont de Charney, who receives a first-rate education but whose lack of faith leads to dissipation. Charney finds himself in successive thrall to “twenty rival truths” of various metaphysical philosophers—“spiritualists, materialists, idealists, ontologists, and eclectics.” Like a college student in a great books course, he immerses himself in each until exposure to a proliferation of truths provokes a universal skepticism; Charney renounces the idea of a stable universe and adopts “chance” as his God. He joins a conspiracy against Napoleon Bonaparte, fancying himself a social “leveller,” and at the end of the first chapter Charney is imprisoned for this crime in a castle-turned-penal institution on the border between France and Italy. It is here that a plant becomes the means of Charney’s salvation.

Botany and Moral Education

To understand how a plant might serve as an agent of moral reform requires us to abandon our view of botany as a strictly empirical enterprise. Nineteenth-century educators and theologians promoted the science as a pious activity that could illustrate the relationship between all of God’s creations. Botany rapidly grew in popularity in America during the first half of the nineteenth century precisely because advocates praised its ability to inculcate good morals. It was the first scientific subject to become widely adopted in early schools for both sexes in large part because the close study of the natural world was believed to promote health and systematic thinking, and to reveal the beauty and order of God’s creation. Botany put students into natural spaces and brought natural objects into classroom settings. And part of the usefulness of botany as a tool for moral education lay in its very materiality. By studying individual plants, students could gain tangible experience establishing the relationship between parts and whole on a small scale, a pattern that could be extrapolated to the whole of an ordered natural world. As botanical educator Almira Lincoln Phelps emphasized in her Botany for Beginners (1829), “[in botany] the objects about which you are to learn, will be placed before you, to see, to touch, and to smell. Thus three of your senses will be called upon to aid the memory and understanding; and as flowers are objects of much beauty and interest, your imagination may also be gratified.” She then added, “Your emotions, too, will be warmed by the thought of His love and kindness who causeth the earth to bring forth, not only ‘grass for the beast of the field, and food for the use of man,’ but a rich succession of curious and lovely blossoms for our admiration and enjoyment.” The standard practice of botany, as Phelps framed it, brought together sensory understanding, imagination, and emotion, all in the service of reverence for God.

Charney illustrates how the materiality of plants could elicit such a reverent response. He is at first “deeply vexed” by the appearance of a “miserable weed” in his prison courtyard not long after his internment, but he quickly grows “amused to find himself interested in [its] preservation.” In particular, Charney is fascinated by the plant’s agency: its abilities to protect itself from frost and rain, and to grow by its own directives. Studying the plant, Charney becomes increasingly “enchanted by the prodigious and immutable congruities of Nature.” Shortly thereafter the man who had once been an atheist finds a way to believe in God.

The path toward religion lies in adopting the habits of a botanist. Studying the stamens and pistils of the flower, “Charney’s perceptions rose till they embraced the vast scale of the vegetable and animal creation. He recognized with a glance the mightiness, the immensity, the harmony of the whole.” This sense of holism arising from his study of Picciola moves Charney to confession: “Oh! mighty and unseen God!—the clouds of learning have too much confused my understanding,—the sophistries of human reason too much hardened my heart, for thy divine truths to penetrate at once into my understanding.” Charney becomes a model student of natural theology: his observations of the plant in front of him lead him toward a sense of divine power across the whole of nature. This sense of natural order correlates with Charney’s increasing respect for the social order, an association that would have been familiar to nineteenth-century readers. Charney’s plot against Napoleon and subsequent imprisonment results from his rejection of the current political hierarchy, yet the divine order of nature offers a lesson about where the individual aristocrat belongs in an equally ordered social universe.

Reviewers praised Picciola for the moral quality of this trajectory toward social order. An 1843 review in Godey’s Lady’s Book hailed Picciola for its goal of “illustrat[ing] the truths of natural religion by a tale” and noted that “This touching story will reach many a heart on whom the elaborate reasoning of [prominent English theologians Joseph] Butler and [William] Paley would produce no effect.” In 1847 another review in Godey’s Lady’s Book praised the “common sense and good taste” of the publishers Blanchard and Lea for putting forth their tenth edition of Picciola with engravings. “A thousand editions of Picciola will not be too many for its merit,” the reviewer continued, praising it particularly for its “moral charms” in “assail[ing] the secret infidelity which is the bane of modern society.” Likewise, the same year a reviewer for the American Agriculturalist extolled “This beautiful little work, which has assumed the position of a classic in several languages,” noting that “For some it will possess a charm, for others, utility, and for all its moral bearing is excellent.”

The Coquettish Plant

For all that Picciola celebrates the moralizing power of botany, Charney’s interest in the plant quickly becomes an infatuation that threatens to destabilize the very natural order that the study of plants is meant to uphold. In his introductory epistle to the story, added at some point during the 1840s, Saintine writes, “There is love in my story, but it is the love of a man for—Shall I tell you? No! Read, and you will learn.” The ellipsis signals that the object of affection is unexpected; reading on, we learn that it is Charney’s obsession with this prison weed that brings about his change of heart and mind. Charney’s attachment here is a conflation of scientific and sexual desire in the context of a plot that becomes increasingly sentimental. The longer Charney observes Picciola, the more he is drawn to the plant and fascinated with its physiology. Picciola progresses from weed to flower to “she,” and Charney softens in his affection for her as he simultaneously wants to understand everything about how the plant lives.

Linnaeus’s sexual classification of plants in the mid-eighteenth century made it common to think of plants in sexualized terms, and to use the sexing of plants as a veiled reference to gender and sexuality in human society. Erasmus Darwin’s late eighteenth-century long poem “The Loves of the Plants” teaches readers about the different botanical classes by anthropomorphizing stamens and pistils, the sex organs. Many other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century literary works inversely use plants as tropes for human behavior, frequently comparing women in particular to flowers on the cusp of sexual maturity. “Blooming” young women, as Amy King has pointed out, were popular in English novels from Austen to Dickens and Eliot, and helped naturalize certain courtship plots. But Picciola engages with another motif of nineteenth-century domestic fiction—not the plant realm as proxy for human society, but the transformative experience of living with plants. That is, the novel invites us to think about Charney’s ardor for an actual plant.

Charney’s study of the plant is matched by his regular amazement. The moment that Picciola first blooms, Charney is so overwhelmed by feeling that he cannot think rationally. “Analysis or investigation seemed out of the question, engrossed as he was by love and admiration for the delicate thing whose fragrance and beauty breathed enchantment upon every sense!” This love and admiration overpowers analysis and translates into an intensely protective feeling. When a storm threatens Picciola, he covers the plant with his own body, and when the wind blows hard, he builds it a shelter using firewood from his meagre stash. This protectiveness is reciprocal: Charney looks out for the plant because it has also rescued him. At one point Charney falls ill and his jailor, believing the plant to have medicinal qualities, prepares some of the leaves for Charney to drink. Charney miraculously recovers and is distressed to learn about the act of “mutilation” that was committed to save him. As soon as he can walk again, he rushes to visit Picciola, but not before he dresses especially for the occasion: “He actually looked into his pocket-glass while he arranged his hair to do honour to his visit to a flower!—A flower?—Nay—surely something more? His visit is that of the convalescent to his physician,—of the grateful man to his benefactress,—almost of the lover to his mistress!” Charney attributes his recovery to the medicinal application of the plant, and feels gratitude in that regard. But the hyperbolic escalation of relation here reveals desire as well as indebtedness. The invitation to imagine the plant as mistress is coupled with scenes of intense male gaze under the guise of natural history:

He had formerly heard, and heard with a smile of incredulity, allusion to the loves of the plants, and the sublime discoveries of Linnaeus concerning vegetable generation. It was now his pleasing task to watch the gradual accomplishment of maternity in Picciola; and when, with his glass fixed on the stamens and pistils of the flower, he beheld them suddenly endowed with sensibility and action, the mind of the sceptic became paralyzed with wonder and admiration!

The plant’s sexual maturity holds Charney in thrall, and Picciola is elsewhere variously characterized as “the enchantress” and “the coquette.” As an object of Charney’s scrutiny, Picciola is also the object of Charney’s affection.

Charney’s desire for the plant is coupled with sexual fantasies about the plant as woman. Locked away in his tower courtyard, Charney dreams of the high society he left behind, fantasizing about being able to “stand gazing” at the crowds of people in saloons or at balls of his past. In the “brilliant crowd” of his reverie, he delights in the possibility of having his choice “among so many consummate enchantresses” but he comes to choose a woman whom he then recognizes to be the human incarnation of his plant: “His feelings were gently agitated by the lovely vision. But how much more when, on raising his eyes to the dark braids of her raven hair, he beheld a flower blooming there, his flower, the flower of Picciola! …the fair maiden and fair flower appeared to melt into each other. The fragrant corolla, expanding, enclosed with its delicate petals the loveliest of human faces, till all was hidden from his view.” Whereas readers would have been familiar with plant metaphors to express human behavior, the inversion here is striking. Charney fantasizes about a woman who is an incarnation of the flower he nurtures.

Such a reversal might reflect new attitudes about the agency of plants. By the time Saintine wrote Picciola, botanists in Europe and America were increasingly debating whether it was appropriate to ascribe feeling to plants. And whereas Charney at one point has difficulty rationalizing his sense of kinship with a “non-sentient being,” his observations of the plant are full of awe for its faculties. These include descriptions of the kind of evidence that naturalists cited to speculate that plants had some kind of sentience that shaped their behavior, for instance the “faculty exhibited by Picciola of turning her sweet face towards the sun, and following him with her looks throughout his daily course.” Beyond mobility, Charney also recognizes Picciola’s ability to mark time, noting that after “reiterated experiments” he is “able to designate to a certainty the hour of the day, according to the varying odour of the flower.” These experiments echo the work of contemporaneous naturalists who marveled at the behaviors of plants without being able to reach consensus as to the meaning of those behaviors.

Picciola might be seen as a literary iteration of this debate, one that highlights how the agency of a plant might cast doubt on humanity’s elevated place in the universe. In his introduction to the 1849 edition, Saintine characterizes Picciola as the book’s “heroine,” a characterization that, if taken seriously, could call into question the Great Chain of Being that botany broadly upheld. The subversive potential of this thinking has implications for the political realm as well. Charney landed in prison because he took umbrage at the emperor’s power. And while botany becomes a way for him to believe in an ordered universe where natural theology correlates with the naturalness of Napoleon’s rule, Picciola’s liveliness threatens to undermine the most basic element of this order.

Conservative Conclusions

But instead, Charney’s radical love for the plant begins to flag. As the novel progresses, Charney decouples his conflation of plant and woman and shifts his attention toward the possibility of human companionship. This marks a turn to the conventional: “Thus passed the days of the prisoner; and after whole hours devoted to inquiry and analysis, Charney loved to turn from the weariness of his studies to the brightness of his illusions,—from Picciola the plant to Picciola the blooming girl.” Eventually, he discovers that the woman he’d pictured as Picciola actually exists in the flesh. She is Teresa, the daughter of the prisoner next door.

Charney’s passion for the plant also makes him less of a perceived threat to Napoleon, who eventually pardons Charney by rationalizing that “He who could submit his powers of mind to the influence of a sorry weed, may have in him the makings of an excellent botanist, but not of a conspirator.” After his pardon, Charney and Teresa marry, and on the final page of the story, readers discover that the plant, having fulfilled its purpose to rehabilitate Charney, has died from neglect. For all that Picciola is the “heroine” of the story, in Saintine’s assessment, “she” exists as Charney knows and needs her. The plant is entirely subjected to Charney’s whims, fantasies, and desires, and sacrificed for his material and spiritual health. Thus as soon as its role has been fulfilled, the plant is cast aside. Once Charney marries and has a family, he ignores the plant. The last two lines of the story read, “The appointed task was over. The herb of grace had nothing farther to unfold to the happy husband, father, and believer!” A more functional conclusion there may not be.

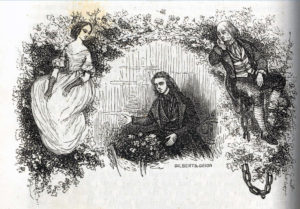

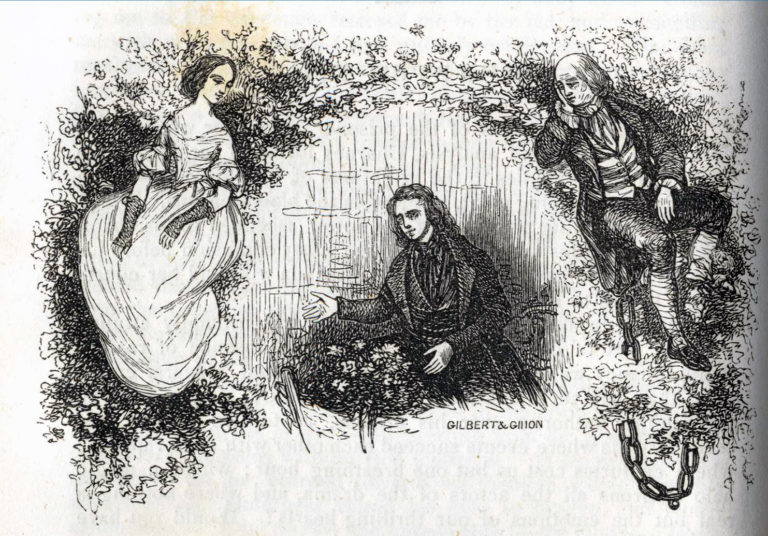

So whereas the sheer amount of attention to the plant may point toward a potentially radical form of sociality, Picciola becomes, in the final assessment, a means to an end. By ultimately redirecting this energy toward a human love interest, Saintine makes the plant an object lesson in domestic values. The conservative conclusion offers a lesson about how plants might foster family feeling. Once this is accomplished, Picciola is expendable. The Gilbert & Gihon frontispiece to the 1847 Blanchard and Lea edition foretells this fate through a constellation of scenes that are populated with various minor human characters. In the centerpiece Charney is depicted flanked by Teresa and her father, and Picciola, one could surmise, is the non-descript shrub toward which Charney gazes.

Yet if Saintine ultimately snuffs the vitality of the plant to underscore the end of its usefulness, every aspect of the plot that precedes it invites us to contemplate Picciola’s liveliness right alongside Charney. Even as Charney grapples with the question of how to understand Picciola’s behavior, the narrator notes that “[w]here reason is paralysed, imagination exercises her influence without restraint.” Readers are invited to imagine both the agency of plants and the very human limits to our imaginations.

Further Reading

For an excellent study of the role of sentiment and sensibility in Enlightenment science, see Jessica Riskin’s Science in the Age of Sensibility: The Sentimental Empiricists of the French Enlightenment (2002). On botany and Romanticism, see Theresa Kelley’s Clandestine Marriage: Botany and Romantic Culture (2012). For associations between women and plants, see Amy King’s Bloom: The Botanical Vernacular in the English Novel (1998) and Janet Browne’s “Botany for Gentlemen: Erasmus Darwin and ‘The Loves of the Plants’” (1989). For more on flora and sexual desire, see Alison Mairi Syme’s A Touch of Blossom: John Singer Sargent and the Queer Flora of Fin-de-Siècle Art (2010). For contemporary discussions of plant intelligence, see Michael Pollan’s “The Intelligent Plant” (2013), Oliver Sacks’s “The Mental Life of Plants and Worms, Among Others” (2014), Peter Wolleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate (2016), Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola’s Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence (2015), Natasha Myers’ “Conversations on Plant Sensing: Notes from the Field” (2015), Michael Marder’s The Philosopher’s Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium (2014) and Richard Mabey’s The Cabaret of Plants: Forty Thousand Years of Plant life and the Human Imagination (2016).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4 (Summer, 2017).

Mary Kuhn is assistant professor of Environmental Humanities at the University of Virginia, where she teaches in the English Department and the Program in Environmental Thought and Practice. She is currently working on a book about the ways in which nineteenth-century domestic writers in the U.S. used ideas about plant life and the global circulation of plants to address pressing political questions.