Lurking in the Blogosphere of the 1840s

Hotlinks, sockpuppets, and the history of reading

I used to have a magazine habit. I subscribed to half a dozen periodicals and sometimes more. Their arrival in my mailbox was a welcome reminder of the flourishing of intelligent life outside of academia. I read magazines for pleasure, distraction, and provocation. The vividness and currency of the best periodical writing offered relief from the stodginess and slow pace of scholarship. The magazine writing I most admired bristled with the personality of the writer and drew on a wide range of dialects and argots. Unlike the literature I studied, these periodicals did not aim to withstand the test of time. They were far too busy with the pressing concerns of the day to bother with such tests. The ephemerality that went hand in hand with magazines’ responsiveness to the world made them the perfect antidote for academic self-importance. They offered a reliable source of excellent writing, which was, nevertheless, content to be discarded.

These days I find I’m turning more and more to Internet blogs for the kind of sustenance I used to derive from magazine writing. The magazines pile up unread as I spend my time hunched over my computer, checking in on my favorite academic, political, and cultural blogs, lost in a seemingly infinite sequence of Web pages as I click my way through link after link. For a while I tried to dismiss my blog habit as the latest in a series of procrastination techniques, one made alarmingly easy and seductive by media convergence. Rather than beckoning to me from the coffee table, these multimedia magazine-substitutes set up shop right here on my computer where my real work is supposed to reside.

Lately, however, I’ve begun to wonder if the time I spend lurking in the blogosphere might actually bring me back to my work, enriching rather than distracting me from my research on the expanding print media of the 1840s. Can living through a volatile period of media shift tell us something about comparable periods in the past? Will awareness of incipient changes in our own reading habits make us better students of the history of reading?

One lesson that can be drawn from the strange allure of blogs is that when new media seek to compete with established media, periodicity matters. Whether blogs focus on breaking news, a topic of concern to a particular community, or the minutiae of ordinary life, they share an architecture built on the promise of the new. Blogs are comprised of frequently updated entries presented in reverse chronological order; they give graphic priority to the most recent entry while allowing past writing to scroll slowly out of sight. While RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feeds now permit readers to “subscribe” to many of their favorite blogs, notifying them when these Websites have been updated, blogs have historically depended on the promise of new entries to encourage repeat visits to their sites. News-based blogs and those devoted to cultural commentary ordinarily piggyback on existing print and electronic media, excerpting items of interest for editorial reframing and reader response. In making their selections, individual bloggers and blogging collectives also reperiodize their source material, transforming the daily newspaper, weekly review—or even, thanks to “Youtube,” the regularly scheduled television show—into a sequence of smaller snippets delivered to readers at shorter intervals throughout the day or week.

The reperiodization of a medium thought to be too slow for the pace of modern life is precisely what Eliakim Littell (1789-1870) had in mind when he founded the weekly periodical Littell’s Living Age (1844-96). A veteran editor of “eclectic” monthly magazines that reprinted the best of the foreign press, Littell prided himself on repackaging selected articles from elite British quarterlies such as the Whig Edinburgh Review, the Tory Quarterly Review, and the reform-minded Westminster Review—along with essays from less prestigious monthly publications—into a moderately priced weekly magazine designed to appeal to the general reader.

The success of miscellanies such as Littell’s Living Age depended on the U.S. Congress’s repeated refusal to pass an international copyright law and on the cultural prestige of foreign periodicals. The stately publication pace of the British quarterlies helped to reinforce their authority, granting an air of thoughtful deliberation to their sectarian or partisan outlook on the world. Littell’s magazine aimed instead to be a fast-moving, broad-minded record of an always changing “living age.” From the perspective of a centralized, hierarchical periodical culture (such as London’s), the eclecticism of Littell’s verged on incoherence, but its editor saw miscellaneousness as the sign of a modern, scientific approach to general knowledge. Drawing its articles from a range of politically and culturally incompatible sources, Littell’s Living Age projected a cosmopolitan openness to the world beyond the boundaries of party, sect, and nation.

Littell’s publishing strategy also shifted authority from writers to editors, placing a premium on editorial judgment. Like many nineteenth-century British authors who achieved widespread popularity in the United States, Charles Dickens bitterly resented the free reprinting of his texts. Dickens was angered by the loss of potential revenue but also by his inability to control the mode of circulation of his writing. As he complained in a letter to Henry Brougham, the foreign author “not only gets nothing for his labors, though they are diffused all over this enormous Continent, but cannot even choose his company. Any wretched halfpenny newspaper can print him at its pleasure—place him side-by-side with productions which disgust his common sense.”

What appeared to Dickens as a fundamentally disorderly print culture was understood by American newspapermen and magazinists to signal a crucial shift in authority from authors to periodical editors and their readers. Magazines and newspapers that relied on reprinting for much of their contents courted readers through their principles of selection. They touted their ability to sift through mountains of print for the most important, valuable, or entertaining items. At one level, Littell’s attempt to appeal to (and produce) a general reader couldn’t be more different than the aggressively partisan, popular political blogs Dailykos and Instapundit. However, both 1840s reprint vehicles and twenty-first-century blogs amplify their own cultural authority through judicious acts of editorial selection. Both modes of publication manifestly rely on a more established press, but both seek to convert their dependency into a form of cultural power.

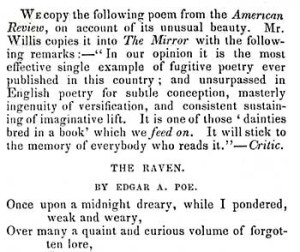

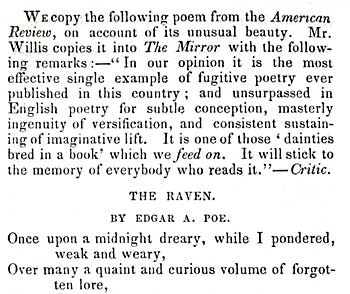

Much of this power resides in their ability to display the fact that the value of a text depends on the history of its reception. Take, for example, Littell’s 1845 reprint of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” which is, more precisely, a reprint of the London Critic’s reprint of the poem. Littell’s version comes complete with a head note that calls attention to the history of the poem’s reprinting, dubbing it “the most effective single example of fugitive poetry ever published in this country.” These nested, reiterated claims for the excellence of the poem reflect back on the reprinter’s judgment in selecting this text and also show the reader that he or she is part of a transatlantic community of discerning editors and readers. Modern literary critics and bibliographers have tended to regard unauthorized reprints as of marginal value, but blogs can help us to see the importance of these visual traces of a text’s place of origin in a literary culture keyed to the value of recirculation, not origination. Bloggers’ routine inclusion of “hotlinks” to the stories they excerpt and the prominence on most blogs of “blogrolls” indicating affiliated Websites make the awareness and cultivation of networks of citation part of the medium itself.

The prominence of these networks of citation and affiliation leaves both the blogosphere and 1840s periodicals acutely vulnerable to the charge that they have failed to deliver on the democratic promise of the new medium. Whether evidenced by the chains of citation that indicate a reprinted text’s travel between and among urban print centers or by the echo effect of firmly held opinions bounced between and among like-minded blogs, both 1840s print culture and contemporary electronic media are dogged by the suspicion that the range of voices represented in a seemingly wide-open medium is narrower than one might think.

Edgar Allan Poe spent much of his early career deriding the coteries who seemed to control the periodical press, author-editors who reprinted and “puffed” each other’s work behind the veil of gentlemanly anonymity. He then spent much of his later career attempting to manipulate this system, using pseudonyms when reprinting some of his own work as editor of the content-starved Broadway Journal, writing anonymous critical notices calling attention to the publication of his fiction in other periodicals, and playing the anonymity and formality of the editorial “we” off against individual authorship.

For instance, in his capacity as editor of the Broadway Journal’s critical notices, Poe distanced himself from a scathing, anonymous review of Longfellow published in The Aristidean, a review that he may or may not have written.

There is a long review or rather running commentary upon Longfellow’s poems. It is, perhaps, a little coarse, but we are not disposed to call it unjust; although there are in it some opinions which, by implication, are attributed to ourselves individually, and with which we cannot altogether coincide.

Literary critics who are interested in the limits of Poe’s oeuvre have argued about Poe’s authorship of this vituperative review, seeking to settle the question once and for all. Poe, by contrast, is clearly invested in preserving the distance between this anonymous text and his authorial name. Periodical culture made it possible for authors and editors to occupy a plurality of positions that could not be reduced to individual identity, to circulate opinions “with which we cannot altogether coincide.”

Blogs have similarly suffered from the accusation that their much-vaunted inclusion of diverse sources and of voices is a sham made possible by pseudonymity. In response, some blogs have instituted stringent rules against “sockpuppetry”—writing under one pseudonym to praise or call attention to writing done under another of one’s pseudonyms. Other outlawed stratagems include corporate attempts at virtual marketing through the use of proxies, or “shills,” and “astroturfing”—using multiple personae to create the appearance of popular consumer demand or grassroots political support. Bloggers’ willingness to risk the credibility of their medium in order to retain the pseudonymity that fuels the expansion of the blogosphere should tell us something about the importance of concealed identities to the history of authorship.

Literary critics have all too often viewed antebellum periodical culture through the prism of twentieth-century norms; they work hard to recover the authors of anonymous or pseudonymous writing and treat the mixed modes of attribution common to 1840s periodicals as a regrettable prologue to the triumphant emergence of the economically self-sufficient author. For instance, critics have been quick to identify a number of pseudonymous tales and sketches that appeared in antebellum gift books and magazines as the property of Nathaniel Hawthorne, rather than pausing to investigate the elaborate naming system that established networks of affinity between and among tales written “by the author of ‘The Gray Champion,’” “by the author of ‘Sights from a Steeple,’” and “by the author of ‘The Gentle Boy.’” And yet the radical expansion of blogging in the past few years, as well as the popularity of posting pseudonymous comments on other people’s blogs, should remind us of the complex pleasures of keeping writing at some distance from the self. The extraordinary amounts of time ordinary citizens spend cultivating on-line pseudonyms and avatars—including writing elaborate “GBCW” (“Goodbye Cruel World”) postings in which these personae dramatically exit the scene—suggest that authors desire to disavow their writing, not only to claim it. The popularity of blogging may well produce histories of authorship that are more attentive to authorial disavowals, histories that would respect rather than compensate for the proliferation of authorial personae.

The furious growth of the blogosphere, despite the difficulty of making a living from the practice, should also remind us of the rich range of motivations for writing that go beyond immediate financial reward. Following William Charvat, historians and critics have generally taken the professionalization of authorship to be the inevitable outcome of the nineteenth-century development of a mass-market for print. They have assumed that economic self-sufficiency was the engine that drove both authors and their publishers. But what if, in a time of media expansion, the certainty of economic reward is a minor consideration next to the thrill of participation in a new medium? What if writers (then and now) are motivated by the possibility of constituting an audience by virtue of addressing one or by the power of a more democratically distributed medium to confer new value on ordinary lives? (W. Caleb McDaniel makes this point in an earlier essay in Common-place.) Perhaps writers and readers are drawn to blogs—and were drawn to the popular print forms of the 1840s—because they offer a sense of belonging to a public, a self-organizing group of strangers without discernable boundaries, which can loosen the bonds of race, gender, status, class, age, or geographic locale. Experiencing firsthand the unsteady, uneven shift of some blogs from after-hours obsessions to full-time, profit-generating occupations may well give us new insights into the lag time between the expansion of print and its successful capitalization. It may also give us new respect for the range of aspirations that galvanize going-into-print long before publishers have standardized payments to authors.

What does it feel like to live in a time of media expansion and media shift? In proclaiming that “the whole tendency of the age is Magazine-ward,” Edgar Allan Poe took aim at the “ponderosity” of the quarterly reviews, arguing that in both tone and content they were,

quite out of keeping with the rush of the age. We now demand the light artillery of the intellect; we need the curt, the condensed, the pointed, the readily diffused—in place of the verbose, the detailed, the voluminous, the inaccessible.

Poe understood that new media require and promote different kinds of writing and can shift the balance of power among existing modes of publication.

I find it both disarming and exciting to watch how blogging has begun to erode the boundaries between media: while the New York Times has incorporated blogs into its electronic edition in order to prop up sales of the printed newspaper, amateur bloggers have in turn begun to seek out official press credentials, and academics such as Michael Bérubé and Juan Cole have turned to blogs to cultivate a wider audience for their expertise. While blogs haven’t yet replaced or displaced the mainstays of my daily reading—the newspaper, the books I teach, the secondary criticism, history, and theory I read for my research, the student writing I’ll turn to any minute now, the novels I read to escape all of this reading—blogging has changed the temporality and the location of my reading practices, tying me ever tighter to the laptop on which I write and, increasingly, read.

Blogging should remind us to ask of the past, not just who was reading or what was read by whom, but also when, how often, and where was reading done? In giving us the term “lurking”—with its connotations of idleness, fraud, and concealment, as well as the possibility that readerly latency might at any time be converted into discourse or action—blogging also prompts us to ask of the expanding print media of the nineteenth century: When are readers potential writers? How might the presumption that readers are potential writers have organized the world of print?

Finally, while in their timeliness and adaptability blogs appear to be ephemeral writing, they may very well surprise us by their durability. Unlike writing for antebellum periodicals, which could be both narrowly restricted in circulation and, due to reprinting, profoundly uncertain in its reach, blogs such as “Dailykos” are now centrally searchable. They have archived their contents and have indexed both postings and comments so that they can be retrieved according to pseudonym. They also offer minute calculations of daily readership based on visits to their sites. Caught up as they are in controversies over their relation to the mainstream media and the relations between individuals and their personae, blogs may end up whetting rather than satisfying my desire for writing that can be thrown away.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.2 (January, 2007).

Meredith L. McGill examines the relations between intellectual property law and literary publishing in American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834-1853 (Philadelphia, 2003). She is associate professor of English at Rutgers University.