Misimoa: An American on the Beach

They called it, simply, the Beach. It was the settlement that grew on the shores of Samoa’s Apia Bay, in the 1800s. What else would they have called it? Like the Samoan lifeblood that sustained it, two rivers flowed into the bay, where a small community grew into a town, in the interstices of the Samoan world. Perched on the edges of Samoan life, in hurricane times it threatened to go into the sea. It was almost literally a beach, a bit ramshackle at first, and the street was coral and sand. What was not Samoan had come over, or from, the sea. It was a community cobbled together from the indigenous and the foreign, built on the cusps of about half a dozen Samoan villages, around a bay that only a real-estate agent would call a harbor.

A missionary settlement in the 1820s brought whale ships to this place, Apia, and whale ships brought much else. Soon there were hundreds of foreigners—resident carpenters and boat builders, groggers and laborers—with Samoans working overtime to keep everyone in profitable order, while missionaries struggled to teach Samoans of a godly white world different from that which they saw. The Beach at Apia was competing with places like Honolulu in Hawaii, Levuka in Fiji, Pape’ete in Tahiti, and Kororareka in New Zealand. All sought to be either a center of the Pacific, or a hellhole, depending on whom you read.

In 1850 the Beach was still a sideshow—the epicenters of Samoa were the capitals of the Samoan world,ancient places such as Leulumoega, Safotulafai, Manono, and Lufilufi. But the next fifty years saw Apia become more and more dominated by foreigners, and Samoa became more and more influenced by Apia. By the 1870s, Apia had become the Pacific’s ground zero for strategic and imperial competition between Germany, Britain, and the U.S. This was the Samoan Tangle, a diplomatic and imperial problem for Germany, Britain, and the U.S. from the 1870s until Samoan partition in 1899. The Tangle brought imperial conflict directly to the Beach, exacerbating the civil wars brewing since the early 1850s, largely, but not solely, because of the competition between the two great Samoan lineages of Sa Malietoa and Sa Tupua.

Most Papalagi (foreigners) were scared or troubled by these difficult and uncertain times, though a few saw in them opportunity. Harry Moors (1854-1926) was a member of the latter group: he arrived on the Beach in the late 1870s, and soon became the most prominent American in Samoa. Moors, born in Detroit, became known to Samoans as Misimoa, of the Beach at Apia.

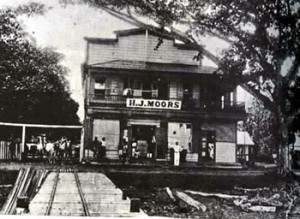

Harry Moors was more than a trader or businessman; he was a writer, a politico, a raconteur, a father, even something of a patriot. He is best remembered outside Samoa for his reminiscences of Robert Louis Stevenson, whom he befriended when the writer came, for health reasons, to live in Samoa in 1890 (Stevenson died there in 1894). Moors began as Stevenson’s agent, and for a while became his friend; but in Samoa, at least, Moors is best remembered for his descendants and his store. Moors was known a generation or so ago as an adventurer, but there was more to Moors than this; his heart and his hearth were firmly anchored on the Beach, which he spent the rest of his life crisscrossing.

Moors saw capitalism in coconuts, and made wealth where others saw only natives. Though his first work in Samoa was for a San Francisco trading firm, Moors soon left the company. A key figure in Samoa’s transition to plantation agriculture, he brokered thousands of the first imported laborers while working as a labor recruiter, also known as a blackbirder, in the Gilbert Islands (modern-day Kiribati). By 1878 Moors was working on Samoan plantations as an overseer of mostly Gilbertese laborers. But the turning point for Moors came when he went into business himself, purchasing some land to grow several crops, though primarily coconuts. Moors trading business meshed well with this, and combined the production and purchasing of coconuts for export, with the importing and sale of trade goods.

The 1890s was a very depressed time in Samoa, as war and a global depression took their toll. Moors’s, however, was one of the few local businesses not in financial trouble. Indeed, it prospered and Moors was able to build an impressive store on the Apia waterfront, a landmark on the Beach that still stands. Moors continued to traverse the Pacific, and even claimed ownership of Niulakita, a guano-rich island in the Ellis group (now Tuvalu). By the early 1900’s, he was the fourth largest employer of Chinese indentured laborers in Samoa and had built a large personal residence and an even larger reputation.

Many thought Moors a sharp trader, and at times people suspected that he was crooked. This was hardly unusual during these years in Samoa. More than once Moors or one of his traders was accused of using doctored weights when measuring coconuts for purchase, and at least once this endangered the life of one of his traders. Even Robert Louis Stevenson, who relied heavily on Moors in his early years, worried that he might be a huckster. Still, Stevenson spent something like $12,000 with Moors as his agent, and also employed Moors to purchase his famous Vailima estate.

Despite their close business ties, and initial friendship, Moors and Stevenson grew apart, largely due to antipathy between Moors and Stevenson’s wife, Fanny. After Stevenson’s death, Moors’s book about Stevenson pointedly wondered whether “Stevenson would have done better work if he had never married.” Fanny, Moors jibed elsewhere, “showed her years,” was “a faded spouse” and was “dictatorially inclined.” There was little love lost—Fanny dismissed Harry as “the village grocer of Apia”—though Stevenson himself never published a bad word about Moors.

When Stevenson arrived in Samoa in 1889, the Samoan Tangle had been strained to breaking point. In 1887 Germany had effectively abrogated its treaties with Britain and the U.S. and placed Samoa under German sovereignty, with Tamasese Titimaea (of Sa Tupua) as symbolic head. After a year of this government, civil war broke out, during which Tamasese was repeatedly defeated. The German navy came to his aid, yet against them the warriors of Mata’afa Iosefo, the leading light of Sa Malietoa, were also successful, in one incident killing or wounding over fifty German sailors. Seeking advantage in the strife, the U.S. and Britain also sent warships. And for a moment these Pacific islands threatened to become more than a footnote to history, as global war threatened to begin right there on the Beach.

But, as Samoans say, God intervened. A hurricane came and caught seven warships bristling at anchor in Apia Bay. They were devastated: six capsized and nearly two hundred sailors, mostly American, drowned. But the disaster only temporarily interrupted the escalating tensions. Mata’afa resumed his pursuit of supremacy, while Germany would only accept Malietoa Laupepa as king. Troubles were set to continue, and Moors was in the thick of it.

Like Stevenson and the majority of Samoans, Moors was steadfast in his support of Mata’afa. Yet unlike Samoans, neither Moors nor Stevenson entirely supported Samoan independence. Stevenson thought Samoans children; Moors thought no Samoan capable of ruling Samoa fairly. Moors’s support for Mata’afa, often cast as Samoan patriotism, was veiled American adventurism, his gun running abetted by U.S. officials and encouraged by both his sense of profit and his strong dislike and distrust of German imperial ambitions. Stevenson thought as much: he intimated that he would have trusted Moors’s political advice fully, “if he were not a partisan, but a partisan he is. There’s the pity.” Moors had become a key player, not only for Mata’afa, helping to keep him active and competitive in the field, but for the U.S., as an American citizen actively and privately working to further U.S. interests.

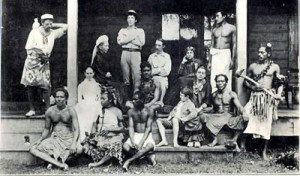

In the midst of this tumult, Moors left on his most adventurous business enterprise yet—the South Sea Islanders Exhibition at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Looking back, it seems Moors deserted a sinking ship, for in mid-1893 Mata’afa surrendered and was exiled to Micronesia (where he remained until 1897). Malietoa did not forget Moors’s disloyalty and forbade any Samoans from traveling with the American to Chicago. In the end, Moors’s “Samoan” village made for a strange display. It was made up mostly of half-castes (people of mixed Samoan and Papalagi descent) and other Pacific Islanders, with only a few full Samoans who had been spirited away.

“It is my object,” Moors wrote, “to present in Chicago a perfect picture of Samoan life under favorable circumstances. Shewing all that is good and attractive and leaving out all that is bad.” This “favorable” representation did not please everyone, and a number of critics shared the “generous indignation at Moors’s troop, and [the] totally false idea” it gave of Samoa.

Still, as a homecoming for Moors, the whole production was impressive, to be sure. Moors had brought with him a huge cargo of Samoan objects, including a seventy-foot canoe of modern design (a taumualua), several smaller watercraft, and three large houses (fale). All this was evidently to good effect. Business in Chicago boomed for Moors and he organized repeat visits to the U.S. He took a group to the San Francisco Mid-Winter Fair, and later toured the Midwest with another group of Samoans. A blossoming impresario, at one point during performances in St. Louis Moors is reputed to have hired a Mexican band to make the Samoan music more appealing to local audiences.

The islanders who went with Moors agreed to rigid terms—strict limits on behavior and dress, and work on Sundays—all for $12 a month. But Samoans seemed eager to accept those terms for a chance to tafao (wander about) overseas. The Samoans who went with him to San Francisco, Moors promised, “o le a toe foi mai i Samoa, ma le fiafia i mea eseese ua latou iloa i la nu’u mamao, ma ni oloa foi ua latou maua mai ai [will return to Samoa happy with the strange things they have seen in distant lands, and the things they have brought with them].”

Soon after first settling in Samoa, Moors married a Samoan woman from a prominent family, Fa’animonimo (Nimo). She was to remain an essential element in Moors’s success, and was known as an extremely smart and capable woman. Moors already had other sons with a woman from Wallis Island (Kane), and from a relationship with the Samoan Epenesa Enari (Mark). Moors recognized and cared for both of these sons. Nimo toured the U.S. with Moors several times, countering suspicions that Moors was only luring her there to divorce her. “If she comes back again still married to Moors,” Stevenson had written in 1893, “I shall think a lot of her savvy.”

Moors’s marriage to Nimo had apparently upset his family. His mother did not approve of her son’s marriage to a nonwhite—one of those “pork-eaters and cannibals,” she is reported to have said. But the marriage between Nimo and Harry ultimately proved a lasting one.

After Samoa was split between the U.S. and German Empires in 1899, Moors’s political adventures slowed down, but did not stop. The German governor thought him active in intriguing against German rule, and was probably right. Then, after New Zealand took over German Samoa in 1914, he seemed to be involved in protests against what many saw as gross misrule. Even shortly before his passing in 1926 he was active in the rising anticolonial movement, the Mau. By then, though, it was his daughter, Rosabel, who was to be a key figure in the anticolonial opposition.

Moors’s daughters—Ramona, Rosabel, Sophia, and Priscilla—united a number of influential Apia families. These daughters all married either prominent whites or half-castes, and were a core part of the half-caste and Samoan elite that centered on the Beach and that lent its support to the Mau. Rosabel married Olaf Frederick Nelson, son of a Swede and a Samoan. As the chief Taisi, Nelson became one of the key Mau leaders in the 1920s. After her husband was exiled from Samoa, Rosabel not only ran Nelson & Sons (which had merged with the Moors Company to be the largest private enterprise in Samoa), but was one of the leaders of the Women’s Mau, which sought to continue protest in the face of the New Zealand colonial government’s repressive use of mass arrest, deportation, and violence.

Moors’s only adult son with Nimo, Harry Jr. (known to Samoans as Afoafouvale Misimoa), was educated in the U.S. and served Samoa and the Pacific for many years, including as secretary-general of the South Pacific Commission. The Moors family remain one of the most prominent Samoan families, still a feature in the city of Apia, where the Moors’s store remains as a vestige of its Beach days.

In his later years Moors was a very active writer. This was partly due to Stevenson’s encouragement, and the main fruit was his 1910 book, With Stevenson in Samoa. In addition to With Stevenson he published some short stories, and was an active correspondent to Samoan periodicals, particularly the Samoa Times. He also left a large body of unpublished works, including two novels, and a series of reminiscences (later anthologized and published in 1986).

Samoa never became entirely American, as Moors hoped it would—though the east is still a U.S. colony, or territory, today. Yet Moors serves as an intriguing window onto the times of the Beach and the Tangle. Moors’s life shows how places as diverse and distant as Kiribati, Tuvalu, Wallis Island, Chicago, and Samoa, were part of a vibrant circuitry. For much of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—Moors’s heyday—there was a Brown Pacific, a huge movement of Pacific Islanders throughout the Pacific, and beyond.

Further Reading:

Moors’s main published writings are With Stevenson in Samoa (Boston, 1910) and Some Recollections of Early Samoa (Apia, 1986). Robert Louis Stevenson’s remarks come from his A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (New York, 1892), and The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Ernest Mehew and Bradford Booth (New Haven, 1994). The other remarks of Moors used above can be found in the unpublished papers of Sir Thomas Berry Cusack-Smith in the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. The source of Fanny Stevenson’s words is her Our Samoan Adventure (New York, 1955). Joseph Theroux wrote briefly of Moors in Pacific Islands Monthly (August and September, 1981), and Tuiatua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi writes in his Ia Fa’agaganaina Oe E Le Atua Fetalai (Apia, 1989). For introductions to Samoan history during this period, see Malama Meleisea ed., Lagaga (Suva, 1987) and R.P. Gilson, Samoa 1830-1900 (Melbourne, 1970). On the circulation of Pacific Islanders throughout Samoa and the Pacific, see my “‘Travel Happy’ Samoa,” New Zealand Journal of History (2003), and on whites and half-castes in Samoa, see my Troublesome Half-Castes (forthcoming).

This article originally appeared in issue 5.2 (January, 2005).

Toeolesulusulu Damon Salesa teaches in the history department and in Asian Pacific Islander American studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; he was educated at the University of Auckland and Oxford University.