Mohawks, Mohocks, Hawkubites, Whatever

The stealthy invaders who dumped the tea on the night of December 16, 1773, “were mostly disguised as Indians…with no more than a dab of paint and with an old blanket wrapped about them…The reason why they dressed this way and called themselves Mohawks is unknown”—this according to Benjamin Labaree in his masterful study The Boston Tea Party. Perhaps the answer can be found in the legendary night scare figures called the Mohocks, who, in gangs, were purported to roam the streets of London early in the eighteenth century.

There is little evidence that the Bostonians called themselves Mohawks before the big tea dump, though a decision had clearly been made that their disguise would be as “Indians.” “Indian,” like “Turk,” “Moor,” and “The Green Man” were terms given bogie men and night dwelling maskers throughout the Anglophone world.

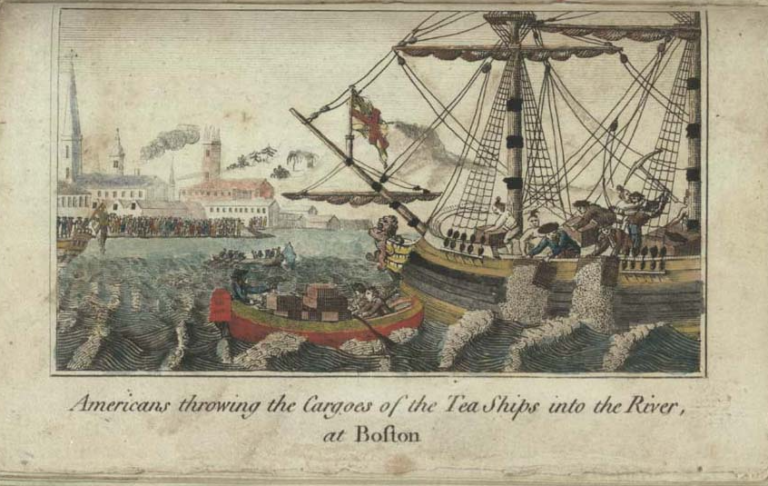

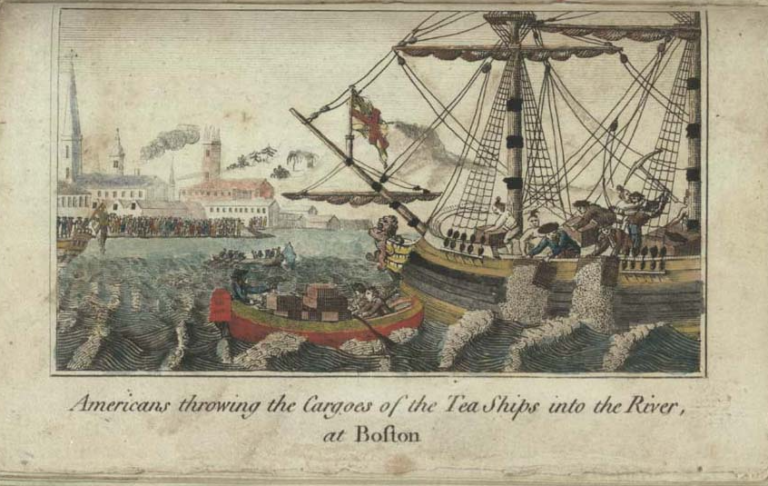

The so-called mobbing had been carefully planned, the participants chosen, and the disguise agreed upon. Those chosen to be Indians were instructed to clothe themselves with old blankets and to black their faces. George Twelve Hewes, one of the participants, wrote that with only “a few hours warning of what was intended to be done” they hastily costumed themselves, smearing their faces and hands “with coal dust in the shop of blacksmith.” Secrecy and silence became the order of the evening. Even though they were representatives of the suitably angry political factions incensed by the tea tax and the patronizing treatment of the British authorities, the tribe proceeded in amazingly orderly and quiet fashion. There were three ships to be boarded and three groups of blanketed figures carrying hatchets, hoes, or whatever other tool came to hand. Each “division” had a “commander” according to Hewes; indeed he was the one appointed to deal with the captains of the ships and to gather the keys to the storerooms so that they might proceed in a quiet and orderly fashion. Hewes remembered that immediately after the event the raiders “quietly retired” to their “several places of residence…without having any conversation with each other, or taking any measure to discover who were our associates.”

The Loyalist Peter Oliver in his not unbiased account of the proceedings noticed, “There was a Gallery at a Corner of the Assembly Room where Otis, Adams, Hawley & the rest of the Cabal used to crowd their Mohawks & Hawkubites, to echo the oppositional Vociferations, to the Rabble without the doors.” Written from London eight years later, Oliver’s notes accurately reflect the Tory talk surrounding the Boston troubles, and “Mohawks and Hawkubites” seem to refer to the tea party participants.

But these terms were far from new. They came into use at the spectacular and unexpected arrival of four Mohawk “ambassadors” to the court of Queen Anne in 1712. Generally called “kings” or “sachems” only three of them were actually Mohawks—the fourth being a Mohican—and none of them were regarded as leaders. They were encountered by many Londoners, not only those who officially received them at court. They went to all of the best tourist locations, dined well though they were eating foods that were far from their usual diets. Wherever they ventured, they created a traffic jam.

After this visit, the word Mohawk took on a life of its own. Rumors began to spread that a night-marauding group of the Hellfire sort made up of young swells called “Mohocks and Hawkubites” was engaged in night raids on unsuspecting folks who wandered into their clutches. They were said to be a secret group of bucks and blades who had taken blood oaths as part of a membership ritual. They marked their victims by slitting their noses with knives or by placing them in a barrel and rolling them down hill. There is no evidence that the group actually existed, but many specific incidents were attributed to its members. If it did exist, it was probably one of many secret societies that existed in the shadows of the men’s club culture that flourished in eighteenth-century London.

Rumors of the depradations of this group coursed through London, creating the Mohock Scare of 1712-13. A play about them was published, though never acted, called The Mohocks, probably by John Gay, later famous as the author of The Beggar’s Opera. Richard Steele in The Spectator of March 10, 1712, refers to them as “that species of being who have lately erected themselves into a nocturnal fraternity under the title of the Mohock Club.” Just how mysterious were the organization, its costume, and its activities becomes clear in Steele’s report: he thought them “East Indians, a sort of cannibals in India, who subsist by plundering and devouring all the nations about them. The president is styled Emperor of the Mohocks, and his arms are a Turkish crescent.” Jonathan Swift wrote to his friend “Stella” (Esther Johnson), asking, “Did I tell you of a race of rakes, called the Mohocks that play the devil about this town every night, slit people’s noses, and beat them…Young Davenant was…set upon by the Mohocks,…they ran his chair through with a sword.”

The Boston tea riot was tied to the boisterous operations of such male voluntary associations, though hardly of the elite sort found in London. Such groups seemed to emerge as an outgrowth of commercial life throughout Europe and especially the British colonies. Philadelphia, Boston, Annapolis, and Charleston were proud of the fact that their level of civility was exhibited in the number of different clubs that had been formed. Most of them were urban clubs run by and for the urban elite, but they were found in frontier towns as well, sometimes constructing one of the first solid buildings as their lodges.

When the aggravation over the tea tax developed organized momentum it arose from a town-meeting style gathering at Faneuil Hall. When it became clear that there were interested parties from beyond the boundaries of Boston, the proceedings were moved to the Old South Meeting House a few blocks away (and somewhat closer to Griffin’s Wharf, where the ships were berthed). Now constituted as “The Body,” all of those who crowded into the building were given voice and vote. Just who was attending is unclear, and their number is disputed; but it was near the winter solstice, the long time of the year, when workers in the countryside took time off from their everyday, every-year tasks to visit the city, and farmers from outlying areas probably joined Boston artisans in this voluntary and spontaneous assembly. The speeches of Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and others assembled at the meeting house went well into the dark and drizzly evening. The cover of dark was sufficient to protect the identities of the rioters from discovery. The taking on of disguises simply amplified the spirit of common purpose and celebration.

The Boston incident, far from being unique, illustrates the long-standing importance and familiarity of what are commonly depicted as spontaneous mob actions.

More commonly found in the face-off between frontiersmen and landowners, White Indian groups were to be found in renter or squatter communities throughout the colonies, such as Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain boys who “played on popular images of wilderness disorder.” The tea situation was greeted with an uproar in many ports, not only Boston. But in that clubbable city, the troubles operated like a magnet, bringing thousands of men to the wharves from various areas, including the colonial backcountry. The Boston incident, in other words, far from being unique, illustrates the long-standing importance and familiarity of what are commonly depicted as spontaneous mob actions. It also illustrates the fact that, whether real or imaginary, discussions of—and rumors concerning the doings of—”Mohawks,” “Mohocks,” and “Hawkubites” had been a part of ordinary peoples’ lives for decades before that fateful December night in 1773.

The best book on the tea party remains Benjamin Labaree, The Boston Tea Party (Oxford, 1964). Hewes’s quotation I take from Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston, 1999). For events of the structure of mob activity in Boston, see Bob St. George’s Conversing by Signs: Poetics of Implication in Colonial New England Culture (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1998) in which various forms of house attack are detailed. The visit of the four kings is described in Richmond Pugh Bond, Queen Anne’s American Kings (Oxford, 1952). The famed court portraits can be seen at Wikipedia. See also Eric Hinderaker, “‘The Four Indians’ and the Imaginative Construction of the First British Empire,” William and Mary Quarterly 53:3 (July 1996). The most important documents of the Mohock Scare are detailed in Neil Guthrie’s “‘No Truth or very Little in the Whole Story’—A Reassessment of the Mohawk Scare of 1712,” Eighteenth Century Life 20:2 (1996): 33-56. The key documents on the scare are best accessed through the guide to the papers of Ernest Lewis Gay, 1874-1916, collector: “Papers concerning the Mohocks and Hawkubites”: Houghton Library, Harvard College Library. Peter Oliver’s comments may be found in Douglass Adair and John A. Schutz, eds., Peter Oliver’s Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View (Stanford, Calif., 1961). This document provides an anatomy of abuses as employed by Tories on both sides of the Atlantic. I survey the white Indian literature in “Introduction: A Folklore Perspective,” in William Pencak, Matthew Dennis, and Simon P. Newman, eds., Riot and Revelry in Early America (University Park, Pa., 2002).

This article originally appeared in issue 8.4 (July, 2008).

Roger D. Abrahams is the Hum Rosen Professor of Folklore and Folklife emeritus, University of Pennsylvania. His books include The Man-of-Words in the West Indies (1983) and Singing the Master (1993) and, most recently, Blues for New Orleans, coauthored with Nick Spitzer, John Szwed, and Robert Farris Thompson (2005). His research interests and publications include reports of historical and contemporary masking and mumming in North America and the Greater Caribbean.