Mount Vernon Makeovers

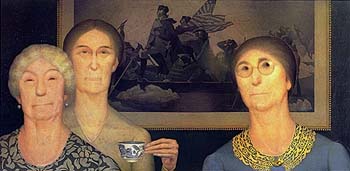

Poor George Washington. Life among the eighteenth-century Virginia gentry was hard enough, what with the strains of wilderness surveying, the challenges of managing (if not actually working) Mount Vernon’s eight thousand acres, and the hazards of fighting all those pesky colonial wars—not to mention the daily indignities of contending with his dreadful dentures. But the twenty-first century may be crueler still to the nation’s first president. Washington, it seems, just wasn’t man enough for our times. Or not, at least, the right kind of man. Lacking both the whiff of sexy scandal that trails Thomas Jefferson in the post-Hemmings era (think Bill Clinton), and the aura of hardscrabble virtue that accompanies John Adams in the post-McCullough era (think Harry Truman), Washington’s TVQ remains low (think Dwight Eisenhower). Grim-faced (the teeth!) and remote, Washington comes across as a stranger, an alien—almost, you might say, as a person from a radically different place and time, a past that’s a foreign country.

Fear not, Sons and Daughters of Cincinnati. Help is on the way. Lest our Founding Father remain shrouded in the mists of the time, a pair of unlikely allies is working diligently to drag Honest George, kicking and screaming, into the twenty-first century. The summer of 2002 witnessed two major Washington makeovers, one at the hands of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, which has owned and maintained the first president’s Virginia home since 1858. The other makeover artist is Mary Higgins Clark.

That Mary Higgins Clark, you ask—America’s self-proclaimed “Queen of Suspense”? The very same. Clark, doyenne of the airport mystery, took last summer’s beach readers on a (very) little trip to the eighteenth century with Mount Vernon Love Story: A Novel of George and Martha Washington (a rerelease of her first-ever novel, Aspire to the Heavens, originally published in 1969). Dedicated to the proposition that all men are created red-blooded and sexy—that Washington was not “pedantic and humorless” but rather “a giant of a man in every way” (ahem)—Clark’s prefatory letter to her readers promises an intimate portrait of “two people I came to respect and love.”

Before you conjure visions of Fabio playing George Washington in the inevitable TV movie, be forewarned: Clark breaks this promise. What Mount Vernon Love Story offers are not steamy sex scenes, of which there’s nary a one (was it the teeth?), but countless moments spent in the throes of hot, throbbing interior decorating. This George Washington, content with chaste blushes and tender embraces in his romantic life, becomes “frantic with desire to see Mount Vernon.” Mount Vernon Love Story is shelter pornography. In the big-screen version, Clark’s Washington might best be played by Martha Stewart in drag.

Far from being pedantic and humorless, Clark’s Washington is henpecked and timorous, the son of an overbearing, whip-toting, Joan Crawford of a mother (First Mommy Dearest?), and the husband of an overprotective, child-toting, porcelain doll of a wife. “[H]eld down, checked, the object of his mother’s whims,” his “teeth [again with the teeth!] set on edge” by the “chaos” of her “grossly untidy” house, the young Washington takes refuge in tract mansion dreams befitting today’s soccer moms. He swears that one day, one day by God, “his home would be warm and welcoming. It would have fine papers on the walls and a marble chimney, papier-mâché on the ceilings and neat mahogany tables . . . George spent much time envisioning that home.”

Luckily, time is one thing Clark’s Washington has plenty of. He doesn’t have to worry about working the land; his trusty and contented servants (almost never called “slaves”) do that. And, fiddle-de-dee, he doesn’t have to worry much about politics, either; some other book can do that. We hear vague murmurs about “troubled days” in the 1770s, or the odd “squabble between Congress and the cabinet” in the 1790s. But for the most part, Clark’s Washington gets to sweat the small stuff: “where flower beds would eventually grow,” the regrettably “hodgepodge effect of the décor at Mount Vernon,” the “dust in the corners” of his quarters in Cambridge. In sum, Clark’s Washington is a hero “suffering the agonies of a housewife”—which apparently include repeated bouts with hemorrhoids and a nervous stomach.

Where the Washington of Mount Vernon Love Story fluffs pillows, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association wants a Washington that busts heads. Last April, Mount Vernon announced an $85 million public awareness campaign “to close an alarming, growing information gap . . . about the nation’s greatest hero.” Concerned, much as Clark was in 1969, that today’s Americans have “lost touch with the real Washington,” Mount Vernon will soon break ground for a new orientation center that will wow the site’s 1.1 million annual visitors with “computer imaging, LED map displays, lifelike holograms, . . . surround-sound audio programs, ‘immersion’ videos, illusionist lighting effects, dramatic staging and touch-screen computer monitors.” At the beating heart of the new facility, two theaters will be devoted to continuous showings of a new “fast-paced 15-minute film.” Produced by Steven Spielberg and Dreamworks SKG, the movie “will provide an action-oriented insight into Washington’s life story.” (Saving Private Washington?) According to the New York Times, the film will be projected “in a theater equipped with seats that rumble and pipes that shoot battlefield smoke into the audience.” Not much room for politics here either, I’m afraid. Forget about the complex ideas Washington was fighting for, and zoom in on a tight shot of a musket.

Surely you’ve already guessed the target demographic for this action mini-epic: where Mary Higgins Clark limns a Washington for women of a certain age, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association is courting fourteen-year-old boys. As Jim Rees, the executive director of Mount Vernon, told the Times, the site needs “to reach not just the minds but also the hearts of eighth graders.” Combining the tools of the plastic surgeon and the forensic scientist with “the latest age-regression techniques,” Mount Vernon wants to restore not only life but youth to Washington. “Most Americans envisage George Washington as a stoic elder statesman,” notes Rees. “But Washington at age 23 was already the action hero of his times.” Who will play this eighteenth-century road warrior? Sly Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger are clearly too old for the job; even Keanu Reeves may be a little long in the wooden tooth. Will Vin Diesel be Spielberg’s Washington, or will Spielberg have the guts to cast Will Smith?

Washington as action hero, Washington as domestic goddess: will the American public buy this silliness? The verdict, so far, is mixed. Mount Vernon would do well to remember that The Patriot, the last major attempt to turn eighteenth-century revolutionaries into box-office gold, bombed with critics and eighth graders alike.

Mount Vernon Love Story may not fare much better. Despite a marketing barrage by Simon & Schuster (the publisher, not coincidentally, of John Adams as well as Clark’s entire oeuvre), Clark’s slim volume nudged its way onto bestseller lists for just a week last summer—mere spray across the bow of McCullough’s juggernaut. History buffs don’t seem to have touched it; a search on Amazon.com reveals that “customers who bought this book” favor the works of Danielle Steele and James Patterson, not those of Joseph Ellis and Gordon Wood. Yet diehard Clark fans hate it. “I have read all of the author’s books and found this one dull,” writes a reader in Cleveland. “Good thing it was small, or I might not have finished reading it.” Notes another “disappointed” fan from Flagstaff, “The only thing Washington truly showed any outward passion for was his home, Mount Vernon . . . he would definitely be in therapy if he was alive now.”

Maybe a session or two on the couch could help poor old George resolve his newfangled split personality. (Diesel or Martha? Martha or Diesel?) Or maybe he’d just beg his therapist for a tonic to relieve the rigors of time travel. Enough with the politics of character, I imagine him pleading. Give me the politics of politics. Put my life back in its times!

This article originally appeared in issue 3.1 (October, 2002).