Mug Books

What did President Abraham Lincoln and dairy farmer Reuben Miller have in common? Both appeared in an 1891 “mug book” for Lake County, Illinois.

Reuben Miller’s family had been in Lake County since 1852. Because “the family was quite large, and his father’s means very limited, he had to begin the battle of life when quite young.” Miller was “bound out” to an area farmer until at age eighteen he served in the Civil War. After the war he returned to farming, married, and started a family. “He has made a specialty of the raising of Ayrshire cattle,” the mug book noted. “With the help of his wife he has made and marketed immense quantities of butter of a very fine grade, for which he has received the highest market price. For some time past however, he has sold milk, and finds it a paying business.”

Abraham Lincoln’s two-page biography tells his familiar tale. Like Miller, Lincoln started life with limited means. His father was “among the poorest of the poor.” “As the years rolled on, the lot of this lowly family was the usual lot of humanity.” After recounting Lincoln’s well-known history, the sketch ends by asserting that “his was a life which will fitly become a model. His name as the savior of his country will live with that of Washington’s, its father; his countrymen being unable to decide which is greater.” Lincoln’s rise from poverty was obviously more dramatic than Reuben’s, but both stories focus on improving one’s life and being a model citizen.

Late nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century mug books are collections of biographical sketches, a curiously rich source for geneologists and historians alike. Typically these books were published only by advance subscription. If a person had the funds to subscribe, he or she (more often he) would have a biographical sketch in the book. For an extra fee, a photograph or sketch would be included. The publishers also might, as in the case of the Lake County mug book, include sketches of presidents and governors. These biographies of the rich and famous helped publishers sell books to buyers who hadn’t subscribed—and who weren’t included among the sketches. The cost of a subscription varied by location and publisher. A subscription, biographical sketch, and portrait could have cost up to sixty or seventy dollars.

Mug books are unique in their detailed portrayal of the lives of ordinary men and women. However tasty his butter, Reuben Miller of Lake County, Illinois, was neither among the county’s earliest settlers, nor a landowner, nor a politician or local leader. He didn’t even own his own farm; instead, he worked the land of a local judge. “The fact of his having been on Judge Blodgett’s farm for twenty-two years in succession,” the mug book observed, “is the highest evidence of his honesty and uprightness, and also of his success as a dairy farmer. He has found his wife an efficient assistant, and the dairy has a neat and most inviting appearance.”

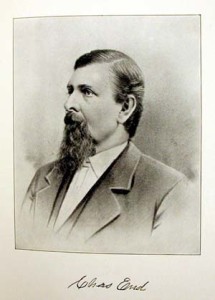

The moral tone of Miller’s sketch, with its testaments to his “honesty and uprightness,” is common to the genre. Of Charles End, a Dodge County, Wisconsin mug book claims, “Naught has ever been said derogatory to his character, but on the contrary all has been said to his credit.” These sketches followed that same pattern of offering nothing but praise. In that sense, they read somewhat like obituaries. After all, these people were paying to be included and the publishers did want them to buy at least one copy of the book.

One frequent mug book publisher attested to the accuracy of its work in the preface by stating, “Every opportunity was given to those represented to insure correctness in the biographies.” Therefore, “the publishers believe that they are giving to their readers a volume containing few errors of consequence.” In other words, the subject of the sketch could edit out anything unflattering and add in whatever they wanted. Errors of omission are likely and factual errors are not uncommon.

While a subscriber need not have achieved fame to be included in a mug book, it did help to be a man and white. Not surprisingly given the time of publication for most of these works, minorities and women rarely appeared. In an 1894 mug book for LaPorte County Indiana, Mrs. Julia E. Work had her own entry of over two pages long. As the superintendent of the Northern Indiana Orphan Home, she was described as “a worthy example of this progressive age and of what can be accomplished by the ‘weaker sex’ when opportunity is afforded.” Julia was one of only eight women featured in this 569-page mug book. She was commended as being “naturally kind hearted and sympathetic” and praised for “her native intelligence and enterprise.” While sketches featuring women were rare, it was not uncommon for them to be mentioned within the sketch of their father, husband, brother, or son. Not only did Reuben Miller’s entry credit his wife with being an “efficient assistant,” but it also listed her parents and where her siblings were living.

As the example of Reuben Miller’s wife’s parents and siblings suggests, mug book entries included the names of more people than simply those to whom a whole sketch was devoted. The table of contents or index usually only listed the names of people featured and rarely included every-name indexes. In some cases, local historical or genealogical societies have created every-name indexes that were published more recently.

To find mug books, you can contact or visit libraries with national collections such as the Newberry Library (Chicago) and the State Historical Society of Wisconsin (Madison) or you can contact the public libraries and historical societies in the area you are researching. Mug books often have titles that start with “Portrait and Biographical Album,” “Genealogy and Biography,” or “Memorial and Genealogical Record.” Some libraries have created indexes to these works. The Newberry Library’s Cook County and Chicago Biography and Industry file is currently a card file that indexes about thirty volumes that have biographical sketches, including some mug books. Ask the librarian about specialized local sources such as that one.

According to the preface for a Will County Illinois mug book, “the value of the data herein presented will grow with the passing years. Posterity will preserve the work with care, from the fact that it perpetuates biographical history that would otherwise be wholly lost.” For all their gaps and transparent biases, these mug books did accomplish what the preface promised. They preserved the life stories of individuals and offered Reuben Miller a place alongside Abraham Lincoln.

Further Reading: The biographical sketch on Reuben Miller can be found in Portrait and Biographical Album of Lake County, Illinois (Chicago, 1891). For information on the price of mug book subscriptions, sketches, and portraits, see Peggy Tuck Sinko, “‘Mug Books’ at the Newberry Library.” Origins 8.1 (1992): 3-5. The sketch of Charles End is found in Memorial and Genealogical Record of Dodge and Jefferson Counties, Wisconsin (Chicago, 1894). The publisher’s statement on accuracy is found in the preface of many mug books. The one quoted here is in Genealogical and Biographical Record of Will County Illinois Containing Biographies of Well Known Citizens of the Past and Present (Chicago, 1900). Julia Work’s biographical sketch is in Portrait and Biographical Record of La Porte, Porter, Lake and Starke Counties, Indiana (Chicago, 1894). The Will County Illinois mug book quoted here is Genealogical and Biographical Record of Will County Illinois (Chicago, 1900).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.1 (October, 2002).

Former curator of local and family history at the Newberry Library, Rhonda Frevert recently became reference services librarian at the Burlington (Iowa) Public Library.