Myths of Lost Atlantis: An Introduction

A blog series dedicated to Philip Lampi

Exploring early American politics one reality at a time.

We sail out

on orders from him

but we find,

the maps he sent to us

don’t mention lost coastlines,

where nothing we’ve actually seen

has been mapped or outlined

and we don’t recognize the names upon these signs.

Okkervil River, “Lost Coastlines“

When you first approach early American political history with the idea of seriously studying it, it can be hard to avoid the feeling that there is nothing you could possibly add. Everything that can be known about the Jay Treaty negotiations or the election of 1828 or the Webster-Hayne debates is already exhaustively covered in numerous books and articles and digested for public edification in textbooks and Wikipedia. If you’re lucky, this feeling dissipates once you get to know the details and nuances and realize that not everything really has been adequately covered. Even then, there are paths you just avoid as overly beaten or simply unmarked.

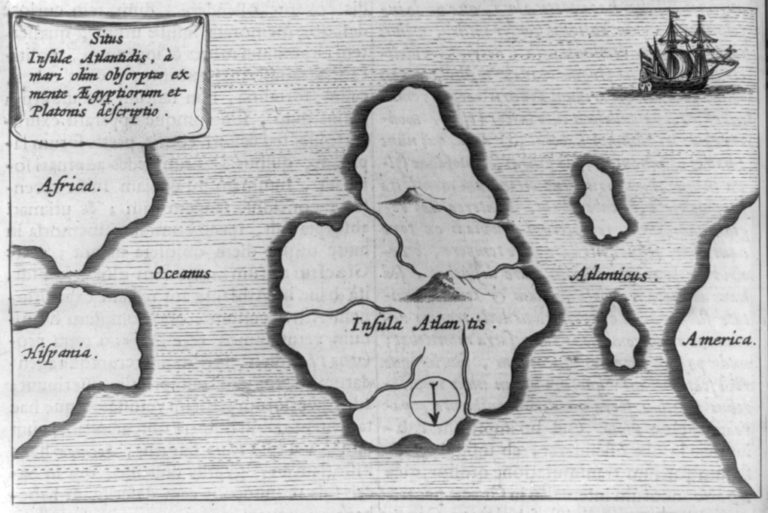

Voting in the Early Republic was one of those topics for me. Reading for comps, it seemed like vote-counting was just about all that a lot of political historians ever did, and you couldn’t even do that, I read, for the early period that most interested me. The data didn’t exist: few of the states voted in the same way or at the same time, especially for president, and almost none of them saved the appropriate records before the advent of what they used to call the Age of the Common Man in 1828. Political scientist Walter Dean Burnham called early 19th-century elections the “lost Atlantis” of American politics, and the seeming lack of data licensed electoral scholars to treat the Federalist-Republican era as a prologue to the real democratic action at best.* Other political historians were increasingly explicit about conceiving early American politics as essentially coterminous with the post-Revolutionary elite better known as the Founders. The philosophical debates and personal relationships of various well-known gentlemen were all that was worth knowing about. In short, there was nothing to see there in terms of popular politics, so I moved on, at least as far as the election results are concerned.

A King of New England

Philip Lampi’s work shocked me out of that attitude. His story has been written up many times by now — the AAS web site has a page of Phil’s press clips — but it never ceases the boggle the mind. Common-Place co-founder Jill Lepore, writing in The New Yorker, called it “one of the strangest and most heroic tales in the annals of American historical research”:

He began this work in 1960, when he was still in high school. Living in a home for boys, he wanted, most of all, to be left alone, so he settled on a hobby that nobody else would be interested in. He went to the library and, using old newspapers, started making tally sheets of every election in American history. His system was flawless. It occupied endless hours. Completeness became his obsession. For decades, at times supporting himself by working as a night watchman, Lampi made lists of election returns on notepads. He drove all over the country, scouring the archives by day, sleeping in his car by night. He eventually transcribed the returns of some sixty thousand elections.

Where professional historians and political scientists shrugged off a whole era because they could not send a graduate student to the library or call up a colleague in Michigan to get the proper data, Phil Lampi committed himself to filling in the blanks of the history books, as a hobby, to be pursued in the spare hours of a rather laborious, hardscrabble life.

In the process of his quest, Phil also made himself one of the country’s leading authorities on the early American press as well as its election returns. At some point, he got at a job at the American Antiquarian Society, the nation’s leading repository of early American newspapers, to be closer to his sources. After many years of photographing the old papers for microfilm and paging them for AAS patrons, making up his tally sheets and helping out interested scholars on the side, Andrew Robertson and John Hench secured National Science Foundation and National Endowment for the Humanities grants that finally allowed Phil to spend some of the work day focusing on his grand project. The grants also launched the process of organization and preservation that has eventually resulted in the immense New Nation Votes database.

Phil is very much a man of the pre-blogospheric era, but in many ways he is a precursor of those self-taught experts who created some of the Internet’s most iconic sites, and the weblog itself, strictly by pursuing their personal interests. New Nation Votes realizes the dream of pioneer Internet history sites like the University of Virginia’s Valley of the Shadow — American history presented with a depth, transparency, and flexibility that no other medium can match. Certainly no other data source can. New Nation Votes users can not only find the once-missing election data, but drill all the way down to Phil’s sources and handwritten notes if they so desire.

All that said, it is in some ways a disservice to overemphasize Phil’s biography. If you talk to Phil at any length, you realize that he did not choose his hobby solely for its boringness. He was also an explorer who sensed the gaps in the available political cartography. He once told me that he enjoyed looking at the voting charts he found in some of the reference books at the public library and wondered why they had so little information on the early part of American history. A true “King of New England,” in the Cider House Rules sense, Phil wondered especially about the political “home team,” as he saw it, the Federalists. Why did the Federalists seem to just disappear from the charts and tables in reference books after John Adams lost? Very early in his data collection, Phil realized that this was not remotely accurate. In New England and selected other localities, Federalists competed in elections and held offices all the way into the Jacksonian era, when party names shifted. Phil was far ahead of his time in rediscovering the Federalists, whom historians now see as a tremendous influence on early 19th-century developments in religion, culture, business, and social reform. The counter-Jacksonian America described in Daniel Walker Howe’s What Hath God Wrought?, for instance, has clear Federalist antecedents.

Explaining the Series

Time to move on to the series mentioned in the title of this post. Blogs being the somewhat confessional medium that they are, let me just admit that I decided to launch this series out of guilt. Here we have Common-Place throwing a special issue on politics, and no one invited electoral historians. Or at least that’s how it might seem. The truth is a bit more complicated, with the small number of people who actually work on early American elections and their lack of availability for the project being one set of reasons, and the greater speed with which other aspects of the issue came together being another. At a certain point, we just filled up, and the Common-Place staff screamed for mercy when I threatened to commission even more articles. The blogosphere seemed to be the answer to the question, how could we pay tribute to Phil — at a time when he is facing serious health issues — and also do some justice to his subject without doubling the size of our already very substantial special issue?

My hope is that this last-resort method of presentation will turn out to be a feature, rather than a bug, as they say in the software business. The series will extend the politics issue chronologically past its publication date, allowing people who weren’t available for the issue proper to get involved and giving repeat visitors to the site something new to look at. This format will also be much more directly interactive. Readers and other scholars will be able to comment or elaborate on the different articles as they see fit, even refute or question or correct them if need be. Should that need arise, we can update the posts to reflect the corrections and comments, using the magic of blogging software. With luck, this might become one of the first experiments in blog-based historical collaboration.

I have lined up a number of guest posters, including Rosemarie Zagarri, Donald Ratcliffe, Matthew Mason, and Andrew Shankman, plus Andrew Robertson and Philip Lampi themselves. A new post in the series will appear every 3-5 days for rest of October, and then continue on from there as needed, with the floor open for further comments and additional contributions for as long as people want to make them. (Writers interested in contributing should contact the management by private email.) The emphasis will be on little nuggets of political history, rather than political commentary, though rest assured that the larger blog will still be carrying my usual commentary as well. While I will admit to my own agenda items of the series, there is no requirement that all the posts agree with each other or fit together into one seamless interpretation. Let a hundred flowers bloom. Or six, as the case may be.

I have decided to set this series up in terms of myths, keying into the “lost Atlantis” motif suggested by Burnham and picked up by Robertson and Lampi. What this means in practice may require some explanation. Myths about early American politics certainly abound, but different ones operate in different quarters of the culture. Some of these myths even seem to cancel each other out. Some citizens and high school textbooks still carry the remains of the old “rise of democracy” narrative, in which the story of America is the story of ever-expanding freedom, or the even older one holding that freedom and democracy never needed to rise because the Founding Fathers gave them to us already whole. Somewhat more knowledgeable others follow the opposite line enshrined in left-leaning popular culture, with expanding freedom still the story but slave rebels and abolitionists and feminists and rural land rioters as the new heroes. Writers in this tradition tend to have little use for any party politician whose credentials can not be burnished in terms of race or gender. Most professional early American historians in recent years have tended to practice a sophisticated version of this latter tradition. All of this is a complicated way of saying that some of the “myths” we will be tackling are traditional cultural myths, others are from the world of textbooks and popular history, while still others come out of the recent historical literature. All are fair game, but we will try to be clear about what sort of myth is being engaged in each case.

One final note: while this series is dedicated to Phil Lampi and we will try to address his work and its subject directly whenever we can, the posts in this series will not be limited to voting and elections. Instead, our mission will be to broadly map some of the lost coastlines and interior features of the continent that Phil has been exploring all these years.

*Burnham seems to have used this line in different ways in different writings. Andrew Robertson explains:

Writing in an essay entitled “The Turnout Problem” (from A. James Reichley, ed., Elections American Style [Brookings Institution, 1987], MIT political scientist Walter Dean Burnham offered what may well be one the most evocative images of political history. “Once upon a time, in the lost Atlantis of nineteenth century politics, American participation rates in both presidential and midterm elections were very close to current participation rates abroad.” The “problem,” as Burnham saw it, was to explain how and why American voting behavior came to deviate from other countries’ practices. Burnham knows a great deal about the history of American voter turnout. He spent innumerable hours as a graduate student holed up in basement archives, poring over the official voting presidential records for elections from 1828 to 1960. More than anyone else except Philip Lampi, Walter Dean Burnham understands that historical research into nineteenth century voting behavior often seems as strange as Captain Nemo’s voyage on the Nautilus.

In academia as everywhere else, imitation is the highest form of flattery. The image of a lost, submerged civilization has been widely picked up by other scholars (in the interests of full disclosure, I am one of them). Joel Silbey, in The American Political Nation, 1838-1893 [Stanford University Press, 1991] entitles his introduction to the book “The ‘Lost Atlantis.’” Following Burnham himself, in a somewhat different usage than I first encountered it, Silbey described all of nineteenth century politics as a “Lost Atlantis.”

If all nineteenth century politics seems strange and exotic, nowhere is the aqua more incognita than the early republic before 1828. Many synthetic histories have taken pains to tell us so. What historians and political scientists couldn’t know had to be dismissed. In the words of one such historian, “the parties of Hamilton and Jefferson…stood as halfway houses on the road to the fully organized parties of the later Jacksonian era.” What these diehard quantifiers could not dismiss was one nagging difficulty: the “turnout problem.” If Jeffersonian politics were a mere prologue to Jackson, why were there more people (and a more diverse group of people) voting in the age of Jefferson than ever voted for Jackson?

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Jeffrey L. Pasley is associate professor of history at the University of Missouri and the author of “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (2001), along with numerous articles and book chapters, most recently the entry on Philip Freneau in Greil Marcus’s forthcoming New Literary History of America. He is currently completing a book on the presidential election of 1796 for the University Press of Kansas and also writes the blog Publick Occurrences 2.0 for some Website called Common-place.