National Violence: A fresh look at the founding era

In This Violent Empire (2010) Carroll Smith-Rosenberg fuses cultural and political history to analyze the violence at the core of U.S. national identity.Common-place asked her: how can we better understand the United States’ long history of racist, sexist and xenophobic violence, and what tools can cultural history offer us as we explore this part of our past?

“Violence,” James Baldwin tells us, (and who would know better than he?) “has been the American daily bread since we have heard of America. This violence is not merely literal and actual,” Baldwin continues, “but appears to be admired and lusted after and is key to the American imagination.” History supports Baldwin’s vision. From the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in the 1790s, through the Civil War Draft Riots, frontier and Klan violence, the Red Scare, the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War, Joseph McCarthy’s war on domestic radicals to our current war on terrorism, fear of all who differ from an idealized vision of the “True American” has driven our public policies and colored our popular culture.

But why? Why did a nation of immigrants, a people who see themselves as a model for democracies around the world, embrace a culture of violence? InThis Violent Empire I traced the history of this violence to the origins of the United States, to the very processes by which the founding generation struggled to create a coherent national identity in the face of deep-seated ethnic, racial, religious, and regional divisions. Their efforts, I argue, have left us with a national identity riven with uncertainty, contradiction and conflicts. America’s paranoia, racism and violence lie in the instability of our national sense of self.

That our sense of national cohesion was hard come by and unstable should not surprise us. The new United States was born of a violent and sudden revolution. For decades after that revolution, the states, far from united, were an uncertain amalgam of diverse peoples, religions, and languages. No common history, no government infrastructures bound them together. Nor did any single, unquestioned system of values and beliefs help unify the founding generation. Rather a host of conflicting political discourses, religious beliefs, and social values destabilized the new nation’s self-image.

As did three deeply incompatible ideological positions that form the core of our national self image. First and foremost is our commitment to the Declaration of Independence’s celebration of the freedom and equality of all men, the universality of unalienable rights. This commitment constitutes the bedrock of our claims to national legitimacy and moral standing. It makes us “the land of the free,” a model for democracies around the world. But two other deeply held beliefs dramatically contradict this self image. Having committed themselves to a universal vision of equality, the founding generation simultaneously envisioned their infant republic as “the greatest empire the hand of time had ever raised up to view,” in the words of patriot and Congregationalist minister Timothy Dwight. Such a vision justified European Americans’ determined march across the American continent, a vision their new Constitution upheld by declaring Native Americans “wards” of a white American state and depriving them of political agency, equality and unalienable rights. But of course the Constitution does far more. Through its Three-fifths and Fugitive Slave clauses, it made the United States the land, not of the free, but of slaves and slave owners. What ideological disconnects and contradictions! What an unstable bedrock upon which to construct a new national identity!

Seeking to efface these discordant discourses as well as constitute a sense of national collectivity for the motley array of European settlers who had gathered on the nether side of the North Atlantic, the new nation’s founding generation had to imagine a New American whom citizens as diverse as Georgia planters (who owned slaves and wanted Cherokee lands), Vermont hard-scrabble farmers (who were committed to the abolition of slavery), and Quaker merchants (who were ardent defenders of Native American rights) could identify with, wish to become, boast that they were.

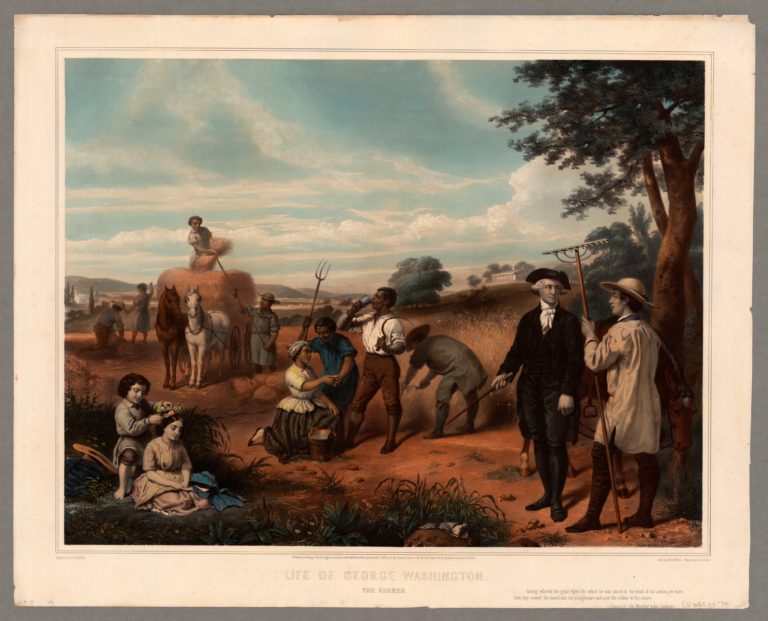

On the pages of the new republic’s rapidly expanding popular print culture—the newspapers, political magazines and tracts, novels, plays, poetry, sermons, press that proliferated in the 1780s and ’90s—the image of a New American gradually took form. How was he initially envisioned? First and foremost, he was a virile and manly republican citizen, endowed with unalienable rights and devoted to liberty and the independence of his country. Secondly, descended from European stock, he was white; no trace of racial mixture darkened his skin. Lastly, he was educated, propertied, industrious and respectable—in short, bourgeois, or at the very least, of the middling classes. Of course, the majority of those residing in the new republic failed to meet these criteria.

How then did the new republic’s print culture go about convincing its readers—and eventually a broad swath of the American people—to embrace their projected New America and the national identity they sought to construct around him?

In support of their newly imagined American, the popular press presented a series of constituting Others, abject and threatening figures, whose differences from the settlers overshadowed the divisions that distinguished the settlers from one another. Their abject qualities, it was hoped, would convince readers to embrace the figure of the New American, to desire to be him or, perhaps even more critically, to be governed by him. Together, the imagined New American and his constituting negative Others were designed to give European Americans a sense of national homogeneity and thus coherence that the reality of their lives did not support. As a result, the new nation’s real ethnic and ideological heterogeneity was denied. Rather than as source of hybrid vitality, it was presented as a source of danger. Difference, diversity became suspect, disdained as polluting, as un-American.

Eventually four principal Others emerged on the pages of the popular press, figures who, only slightly refigured, remain with us today: the disorderly and destructive poor (initially embodied as Shay and Whiskey rebels—later as genetically deformed Jukes and Kallikaks and today as inner city gangs, “welfare mothers,” and illegal immigrants); foolish and dependent women; savage Native Americans; and initially enslaved and always inferior African Americans.

But these Others would not stay other. Time and again on the pages of political magazines and tracts, plays and novels, the New American’s Others fused with him, problematizing his manliness, his claims to republican virtue. Distinctions between European and Native Americans, free and slave labor, collapsed. Masculinity appeared more performed than real. With each collapse of difference, the stability of the new national identity grew more uncertain. The republican press turned upon the Others with rage born of frustration and fear. On its pages the New American and his Others merged in a violent, at times deadly dance of sameness and difference—a dance that enmeshes us to this day. In This Violent Empire, I carefully trace the collapse of difference and the rhetorical rage that collapse engendered.

In my efforts to trace the processes by which our national identity took form, I found traditional historical narrative structures and forms of evidence insufficient to the task. Increasingly I turned to literary critical practices (rhetorical analyses; close readings not only of political texts, but of novels, plays, poems, boldly intermixing genres) and to poststructural and postcolonial theory, seeking ways to penetrate the maze of contradictions and instabilities that enveloped the founding generation’s efforts to create a national sense of self. In the process I came to think of national identities not as the products of literal experiences (the exigencies of the revolutionary struggle; the decades of resistance to British commercial and political regulations) but as rhetorical constructions, composites of conflicting discourses, multiple, layered, fluid, often contradictory. National identities are designed, British cultural theorist Stuart Hall tells us, to “stabilize, fix … guarantee an unchanging oneness or cultural belongingness.” They provide citizens with a sense of “history and ancestry held in common … [a sense of] some common origin or shared characteristics,” no matter how artificial, how fictional that sense of commonality. At the same time, they depend on patterns of systematic exclusion. Again Stuart Hall: “Identities can function as points of identification and attachment onlybecause of their capacity to exclude … The unity, the internal homogeneity, which the term identity treats as fundamental is not a natural but a constructed form of closure … constantly destabilized by what it leaves out.” Those left out constitute the boundaries of our natural belonging.

But boundaries are porous and deceptive. Within their confines, we bond with other national subjects, confirming our similarities, no matter how imaginary those similarities may be. Outside these boundaries, our Others hover, threatening to penetrate and pollute our sense of national unity. Seen thus, boundaries and Others are oppositional forces. But boundaries not only divide but connect us to our Others. They are those points where self and Other are in closest contact. If we think of actual national boundaries, those excluded stand just on the other side of what is often a thin, imaginary line, at times literally a line in the sand. On either side of these boundaries, borderlands stretch, liminal spaces of fluidity, hybridity—and transgression. Within these borderlands, our Others beckon to us. Emblems of the proscribed, they point to forbidden possibilities, tempt us down prohibited paths. Consciously or unconsciously, we seek to incorporate our Others, at times in response to deep-rooted fears of isolation and loss, at other times, for qualities we imagine they have and long to make our own. At still other times we turn from them in disgust, for, as often as not, they are imaginative projections of our own worst qualities, our dark mirror images. To paraphrase Pogo, we have met our Other, and he is us. National identities, dependent on distinctions between our selves and our Others, are illusory and unstable.

All this may seem terribly abstract and theoretical. Let me attempt to make the abstract concrete by examining an incident that occurred at the beginning of George Washington’s presidency. A puzzling but telling example of the complex relation that tied European and Native Americans to one another, it will, I hope, illustrate the layered and uncertain nature of national identities, the contradictory relation between the national subject and his Others. This example will also, I trust, demonstrate the ways cultural historians can contribute to our understanding of political processes of nation building.

On July 21, 1790, a flotilla of ships dotted New York harbor (then the nation’s capital), eminent citizens gathered and a delegation of Creek warriors stepped ashore to sign a treaty of peace and friendship with the new republic. Prominent among those greeting the Creek delegates were officers and members of New York City’s Tammany Society. Proudly proclaiming themselves “sachems” and “braves,” carrying bows, arrows and tomahawks and bedecked in “Indian” costumes, they had marched from their “Great Wigwam” (as they called their clubhouse in the old Exchange Building on Broad Street) to Coffee House Slip to welcome the Creek delegation. From there, they escorted the Creek warriors first to the home of the Secretary of War and then to President Washington’s residence, where they were joined by the governor of New York, senators and representatives from Georgia, army and militia officers. The day ended with a state dinner, attended by the Secretary of War, the Governor of New York, the Creek delegation, and the Tammany “braves.” The historian of the event reported that the Creek delegates were “very much pleased” to see the Tammany members in full “Indian” costume.

Why would hardworking European American shopkeepers and artisans (the Society drew its members primarily from the city’s middling and laboring classes, and included a number of newly arrived and politically radical Irish immigrants) parade down crowded streets in feathers and war paint? (Nor were Tammany “braves” and “sachems” the only European Americans to publicly play at being Indians. From the 1720s on, elite Philadelphia merchants and southern planters had celebrated May 1 as St. Tammany’s Day, dancing around May poles festooned with native American flowers, drinking and feasting long into nights that ended with the burning of St. Tammany in effigy.) Repeatedly during the eighteenth century and at no time more intensely than during the century’s last three decades as the new republic took form, European Americans had engaged in savage, often genocidal, warfare with Native Americans. Captivity narratives and tales of Indian warfare (the new nation’s first best sellers) repeatedly represented Native Americans as savage murderers, sadistic torturers, heathens who lacked any sense of God or, almost as telling, of private property. If any figure stood in the popular press as the European American’s dark and dangerous Other, it was the Native American warrior. How can we begin to understand what led European Americans to playfully don the garb of their savage enemies, to play the surrogate, the counterfeit Indian?

I sought the answer to this question in the nature of surrogacy itself. Surrogates are officially appointed successors, deputies with authority to represent an absent one, to act in his place. Since their first settlements, European Americans had represented themselves as God’s appointed successors to America’s indigenous peoples with jurisdiction over their estates, that is, the North American continent. Because European Americans would use native lands far more productively, native lands were rightly theirs—along with the name “American.” But European Americans did not need to stick feathers in their hair or coat their faces with war paint. They acquired the rights to land, name and authority through war and diplomacy, not charades and masquerades.

And Tammany performances were just that, charades, masquerades, performances. Performances assume audiences and convey social and political messages. Tammany’s most obvious audience was of course the Creek delegation. One can only imagine what the Creek warriors thought of New York artisans in ersatz “Indian” garb. Tammany’s message, however, was far from obscure. In parodying native practices, Tammany members declared that Manhattan was no longer an Indian island, that European Americans had indeed replaced Native Americans as rulers of America. Even more, Tammany braves’ mimicry proclaimed European Americans’ power to misrepresent and recast those they claimed they were replacing in ways that served their own social and political needs.

The Creek warriors, however, were not the Tammany’s only audience; their fellow Americans constituted a second, perhaps even more important audience. Mimicking Native Americans, Tammany’s middling and immigrant members mimicked earlier elite European Americans (merchants/planters) mimicking Native Americans with their May Day festivities. Tammany artisans thus enacted a form of social democracy. Not only did they insist on their equivalence with earlier colonial elites, they declared their active citizenship by publicly participating in affairs of state, standing shoulder to shoulder with President Washington and his cabinet. For middling artisans and radical Irish refugees, that was a very important political assertion.

But we have to consider still more complex aspects of surrogacy. Performance theorist Joseph Roach argues that societies use surrogacy to imaginatively mediate their experiences of radical social change and loss. Certainly, the new Americans needed cultural instruments through which to articulate and ameliorate the radical social, demographic, and political transformations that had marked their lives: their loss of their centuries-old British identity, their sense of being a solitary republic in a sea of monarchies, their fears of being isolated white settlements on the lip of a red continent. Few relations were more traumatic than those between European Americans and Native Americans. The figures of both the savage, terrifying Native American and the savage, terrifying European American who had relentlessly battled him had to be domesticated, incorporated into the ongoing civil and orderly world European Americans worked to create. Chanting make-believe Indian songs, stitching beads and feathers onto their costumes, middling New Yorkers stitched carefully re-formed and tamed memories of their nation’s conflicts into the ongoing psychic and cultural fabric of their new Republic.

But the July event on Coffee House slip points to even more complex forms of Othering and its destabilizing potential. Tammany’s mimicking was not simply a determined assertion of white power. It was also an anxious admission of need. As Philip Deloria has pointed out, European Americans needed to feel connected to the American continent, to become one with the land—and with its indigenous peoples. While condemning them as sadistic savages, European Americans believed Native Americans garnered true nobility from their association with the land: the love of freedom that only the land’s vast expanses could give; a sense of honor, uncorrupted by the niceties of refined culture; and, above all, a fierce, wild courage in defense of liberty and honor. It was these qualities European Americans felt they desperately needed if they were to prove themselves different from, more virtuous, more liberty-loving, than Europeans. To maintain their uniqueness from Europe, they had to embrace their Other, the Native American, reimagined as the Noble Savage. Put another way, as European Americans romantically imagined Native Americans merging with the land, so they romantically imagined themselves merging with Native Americans. The Native Other was no other after all.

However, their difference from Europeans rested on no more stable ground than their difference from Native Americans. Incorporating the image of the Noble Savage, European Americans incorporated a European literary trope, an image born of European reformers’ desires to use an idealized, imaginary Other to critique the corrupt practices of Enlightenment Europe. How ironic: the figure of the Native American as scripted by elite European philosophes and performed by European Americans, initially for elite audiences during the colonial period but ultimately by Irish political refugees in Jeffersonian America—this was how the whitening of America’s national identity was staged.

But still confusions mount. In many ways, European Americans desired just that: to position themselves as Europeans were positioned—heirs of the Enlightenment, bearers of civilization, polished gentlemen. Although needing to perform the virile American, they felt an equally strong need to perform the enlightened and cultured (European) gentleman. For them, both roles were deeply entwined. It was as if the new Republic’s national identity were played out on a revolving stage. At one time the erudite gentleman claimed the spotlight, at other times, the noble warrior did. Ultimately they fused, for European Americans could not disentangle their two roles. The urban gentleman without the noble warrior would have appeared too effete, too European, to build an American national identity around. The noble savage without the urban gentleman would have seemed too brutal. Combined, they strengthened European Americans’ self-presentation. But they also confused that presentation, revealing the European American to be a deeply divided and contradictory figure, unable to escape fusion with his constituting Others. Needing to consolidate a national identity, the new republican press turned upon its recalcitrant Others with rage. They were indeed dangerous, seductive, deceptive enemies. They must be expelled from the nation body politic—with violence if necessary.

In This Violent Empire I sought to trace the United States’ long history of racism, sexism, xenophobia, and paranoia to the very origins of the new nation and the struggles of the founding generation to create a sense of national coherence and unity. But rather than celebrating the true diversity that is the United States, the founders (and we to this day) celebrate a fictionalized vision of ourselves as a homogenous people, a people who, again in Timothy Dwight’s words, “shared the same religion, the same manners, the same interests, the same languages … and principles.” All who differed must be excluded. We see this operating from the nation’s opening decade with the passage in the 1790s of the Alien and Sedition Acts, the Naturalization Act, the Enemy Friends Act, legislation that aimed at the arrest and deportation of feared aliens, “terrorists” in the words of President John Adams, whose support of the French Revolution his administration read as undermining national security and cohesion. Many of us still think of ourselves as a people made cohesive by our sameness, not our hybridity, united behind our picket fences, “as American as apple pie.” We thus render our diversity suspect, see difference as the parent “of endless contests, slaughter and desolation.” Even more significantly, rather than facing the deep-seated ideological and moral quandaries embedded in “the United States’ dilemma,” we turn our fury on those who disturb our imaginary homogeneity, see our polyglot and multicultural cities not as emblems of an empowered hybrid culture (a culture admired around the world) but as sites of pollution and national danger. The most powerful nation on earth, we seek security in increasingly fortified borders—in higher walls, klieg lights, border guards, body scanning and constitutionally questionable domestic surveillance. Displacing our feared diversity on to imagined Others, we turn upon them with violence.

Carroll Smith-Rosenberg is the Mary Frances Berry Collegiate Professor of History, Women’s Studies and American Culture, University of Michigan, Emerita. The author of several books and more than 40 essays on American history and culture and women’s history, she has twice received the Binkley-Stephenson Award for best article in the Journal of American History. Her most recent book is This Violent Empire: The Birth of an American National Identity (2010).