New-York Knicks Reconsidered

Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein on Washington Irving, Aaron Burr, and the lost political and literary world of early New York City

Professors Isenberg and Burstein sat down for a dialogue about the convergence of their research in one of the early republic’s least-understood political corners.

How does one speak of Aaron Burr and Washington Irving in the same breath?

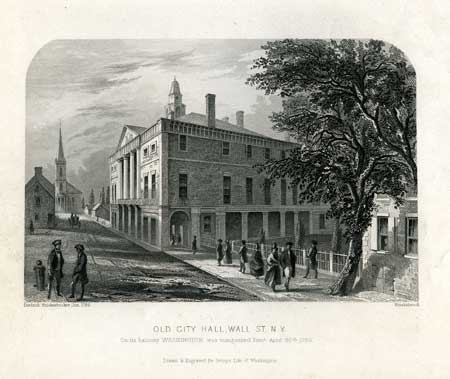

Burstein: First of all, they shared the island of Manhattan for a good many years. Washington Irving was the youngest in a large family of merchants with both literary and political ambitions. The brother with whom he was closest, Peter, ran as a Burrite for the New York Assembly and was the editor of the Burrite newspaper, the Morning Chronicle. The oldest Irving brother, William, served two terms in the House of Representatives as a Republican. John Irving, a lawyer and later a judge, hung out his shingle at the Wall Street address that Burr had recently occupied. Washington Irving, trained in the law, briefly worked there, too. Just before his first voyage to Europe, in 1803, twenty-year-old Washington had breakfast with Burr and absorbed his advice on how to profit from his time abroad.

Isenberg: Burr’s appeal to the Irvings was the same as his appeal to other young New Yorkers looking to rise in society by attaching themselves to a politician sympathetic to their ambitions. Burr was a patron of the arts—the patron, for instance, of the well-known artist John Vanderlyn; Washington Irving was an incurable theatergoer and theater critic in his New York years and would pal around with painters and poets all his life. His brother William, the congressman, belonged to a literary society and wrote doggerel poems that formed companion pieces to his soon-to-be-famous brother’s occasional pieces. In a letter to his daughter Theodosia, who was Irving’s age, Burr, when vice president, eagerly praised the young writer’s satirical essays about Manhattan society.

How did Burr figure in Irving’s writing?

Isenberg: During Burr’s 1807 treason trial, Irving traveled to Richmond, ostensibly to aid in Burr’s legal defense (though Irving had little confidence in his legal skills and no experience trying cases). He was really in Richmond to observe and report back to Burr’s New York crowd; Sam Swartwout, Burr’s companion who was threatened with prosecution, had been Washington Irving’s staunch friend for years. Present in the courtroom, Irving wrote deliciously about how Burr watched his accuser, the notoriously self-important deceiver General James Wilkinson, enter the chamber: “He stood for a moment swelling like a turkey cock, and bracing himself for the encounter with Burr’s eye.” Burr, in complete control of the moment, briefly took in the whole girth of the man and then with perfect poise returned to the conversation he was having with his counsel—it was thoroughgoing contempt without a hint of concern, and for Irving it encapsulated the entire injudicious trial. Irving’s description of Burr is that of a man of audacity, poise, meticulous self-control—the height of masculinity in this period and the same qualities modern Americans came to admire in Humphrey Bogart and Clint Eastwood.

Burstein: In 1809, the work that established Irving’s national reputation, his History of New York (also known as Knickerbocker’s History) featured a demeaning portrait of President Jefferson (“William the Testy”) as an inept dreamer, whose embargo was toothless and who believed that frothy proclamations could replace the defense establishment; it also included a brilliant send-up of the pompous Wilkinson, “William the Testy’s” favorite commander, whom Irving named Jacobus Von Poffenburgh in the mock-history. Irving appreciated Burr’s political skills and wrote feelingly about the scandalized vice president’s confinement in a dank cell during one part of the trial. The writer was incensed that the government had put Burr in an “abode of Thieves—Cut throats & incendiaries” simply to “save the United States a couple of hundred dollars.” Irving’s short story about an unfairly ostracized stranger, “The Little Man in Black,” published shortly after the trial, also reflected the treatment of Burr by those who had turned on him. Short in stature, he was familiarly known as “Little Burr.”

How did Burr’s rise in New York politics establish him as a possible candidate for national office?

Isenberg: Burr established his own faction, which offered a different message than that espoused by the other factions in New York politics—the Schuylers (Hamilton’s supporters, who were also associated with his father-in-law, Philip Schuyler), Livingstons, and Clintons. Rather than Jeffersonian agrarianism, he promoted commercial republicanism. After Burr served in the U.S. Senate in the 1790s, he returned to New York and ran for the state assembly at the end of that decade. Here he established an important network of supporters and advanced legislation promoting his brand of republicanism. In 1799, he backed internal improvements and fairer taxes, protested against the Alien Acts, backed debt reform, and sought to enact more democratic suffrage laws. He also created the Manhattan Company, forerunner to the Chase Manhattan Bank. The Manhattan Company, which was initially controversial, was the first New York bank to give banking privileges to the middling and even lower classes. Burr’s reforms were progressive and drew merchants and mechanics into the Jeffersonian party. One Virginian wrote James Madison that the very existence of this bank would serve to make Jefferson president.

What makes the folk tale “Rip Van Winkle” political?

Burstein: The story, so popular that it was translated for the stage and performed across the country from 1829 until the end of the century, addressed matters of nostalgia and identity, personal and collective. While Rip starts out ignorant of the larger world as an inattentive subject of the king, at the end of his time-bending journey he gets to enjoy life as “a free citizen of the United States.” His shrewish wife, who dies shortly before his return from the mountains, can be seen to symbolize the persecution of Britannia; his daughter, who rediscovers him after his twenty-year sleep and compassionately takes him in, is a symbol of the American republic at peace. Rip, a good-for-nothing before the Revolution, is transformed into a popular village storyteller, making eyes light up when he invokes the magic of a dreamlike past; similarly, Americans of the 1820s (the decade following the 1819 publication of “Rip Van Winkle”) write storied pieces in their newspapers, celebrating democracy’s universal appeal. Steeped in nostalgia for the Revolution, they are full of praise for dying veterans and dying founders, as they near the jubilee commemoration of the Declaration of Independence. They cast the American past in comfortable terms, progressive terms, even terms of moral perfectibility. Irving’s writings from this point forward, like those of his fellow New Yorker James Fenimore Cooper, chart historical progress by heralding the courtesy and affability of the nature-taming characters who best symbolize the republic.

How does Burr challenge the “founders chic” tradition?

Isenberg: Many who write books about the founders focus on mythic “character” rather than the real political environment, the nasty manner of politics. Much of what has been written about Burr has been taken from unreliable sources, which include accounts fabricated by his political enemies. Few scholars have scrutinized the sources they use when they portray Burr as a villain. As the Judas of the founding generation, he has been reduced to a two-dimensional character, a foil, in contrast to his supposedly more virtuous peers. I discovered that his reputation cannot be adequately explained in terms of character—history is never that simple. Remarkably, many have accepted Hamilton’s views of Burr, ignoring the fact that Burr was his principal rival in New York politics. “Founders chic” tends to ignore the viciousness of partisan activities. For example, the role played by anonymous newspaper editors, such as James Cheetham of the American Citizen, has been completely ignored: Cheetham spent three years filling the pages of his newspaper with personal attacks against Burr. Sexual slurs were his favorite weapon. He compared Burr to a libertine, and his young male followers were called “strolling players”—a euphemism for male prostitutes. He accused Burr of having sex parties in his home to lure black male voters to his ticket and compared Burr’s home to a bordello, with mirrors on the ceiling, for lavish orgies. Cheetham had first supported Burr and later switched sides, giving his support to Burr’s rival within the Republican Party, DeWitt Clinton. Clinton wanted to be governor of New York (and eventually was), while maneuvering to have his uncle, George Clinton, elevated to the vice presidency (which he eventually was, as well).

Burstein: It is worth noting that DeWitt Clinton, lauded in history for his promotion of the Erie Canal, was also small-minded and petty. He published a pamphlet, a self-serving tirade, in the wake of Washington Irving’s success with Knickerbocker’s History, in which he sneered at the modest origins of Irving’s upstart literary set and called Irving’s satirical masterpiece “intolerable.” He wrote of his own literary abilities in the third person: “Mr. Clinton, amidst his other great qualifications, is distinguished for a marked devotion to science—few men have read more.” Irving, he wrote, “cannot read any of the classics in their original language…I find him barren in conversation.” What this proves, at bare minimum, is the stinging effect and enduring power of political satire.

What do your biographies of Burr and Irving add to our understanding of the conduct of politics in early America?

Isenberg: Burr demonstrates that you can’t understand the founders unless you understand state politics. The founders were not national figures who transcended state politics; rather they were attached to their states, and their rise to power came through the support they received in their states. Politics was never just about high-minded ideas but was also about newspapers, where harsh battles were waged on a daily basis. Mudslinging in the newspapers exceeded what we experience in today’s media. Democratic politics from the very beginning relied on scandal. Newspaper editors like Cheetham brought the Grub Street tradition of scandalmongering over from Great Britain, and it quickly adapted to the American party system.

Burr’s story also reminds us of the importance of rivalries within parties. Early American politics was not simply a contest among a handful of “great men”: Washington, Adams, Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison. Nor was it only a partisan struggle. The election of 1800—in which Jefferson and Burr received the same number of votes, creating a tie and havoc in Washington—revealed a deeper tension. A profound sectional divide existed between Jeffersonian Republicans in New York and Virginia; each group, with jealous determination, sought to defend and broaden its power. The New Yorkers did not trust the Virginians, and vice versa; their alliance was precarious and tentative.

Burr’s success was owing to his role as a mediator. In 1799, he united the squabbling Republican factions in New York to support the Manhattan Bank and then again to secure the election of Jefferson. President Jefferson realized he could secretly align with George and DeWitt Clinton, to play off the New York factions against each other. Burr was expendable, and his mediating role was no longer necessary. By 1802, Jefferson was already thinking about preparing his trusted political lieutenant, fellow Virginian James Madison, to be his successor. Jefferson kept control of the Republican Party and kept the presidency in the hands of the Virginia dynasty for twenty-four years, while New Yorkers fought among themselves. Though Dewitt Clinton set up his uncle to run against Madison in 1808, the maneuver failed—it did, however, demonstrate the continuing sectional rivalry within the party.

Neither George nor Dewitt Clinton possessed the political finesse to unite New York Democratic Republicans, let alone build a winning northern coalition. Clinton lacked Burr’s qualities. Burr had a national reputation and strong support in New England, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and the western states—he was the only serious candidate who might have challenged Madison. Jefferson’s break with Burr cannot be explained by character or merely personal distrust—it had to do with sectional politics.

Recovering Burr’s role in politics also forces us to concede that the founders lived in a larger social world. Virtually every one of them engaged in risky speculative ventures—even Abigail Adams was a bond speculator. George Washington made much of his wealth as a land jobber, Madison speculated in lands in New York, and Monroe invested in land in France after the French Revolution. Hamilton’s close friend, William Duer, whom he appointed as assistant secretary of the treasury, concocted a grand speculative scheme in government securities—only to be carted off to debtor’s prison in 1792. Though Burr’s bad investments have been reduced to a character flaw, the truth was that he was minor player compared to Duer and others.

For fairly obvious reasons, filibustering and land speculation went hand-in-hand. In 1805, Burr began thinking about the possibility of organizing a filibuster into Spanish territory. A filibuster was a private army without government sanction. Burr and many of his supporters, including several prominent senators and ex-senators like Andrew Jackson, avidly endorsed toppling the Spanish “Dons” and claiming the land for the United States. Burr was not alone in this dream. In 1798, Hamilton thought of leading an army into Mexico as part of Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda’s filibuster. As secretary of state, Jefferson did nothing to stop his friend George Rogers Clark from mounting a filibuster in Louisiana in the early 1790s. President Madison looked the other way when Americans invaded western Florida during the War of 1812. Monroe, as secretary of war, believed the United States should invade Canada and Florida during the War of 1812. Lest we forget, Texas independence in 1836 was also the result of a filibuster.

Burr’s activities are treated as anomalous, his so-called conspiracy a mystery to be solved rather than a reflection of the nation’s ongoing struggle with European powers in North America. From the Revolution forward, America had Canada in its sights and used the language of liberty (freeing oppressed colonized people) to justify conquest. Expansionist aims within a global perspective are missing from portraits of the founders.

Burstein: Politics was the most alluring forum for literature in the postrevolutionary era. Irving exemplifies the type who made his name by writing his way out of obscurity. His clever newspaper essays in the Morning Chronicle, under the invented pseudonym of Jonathan Oldstyle, were succeeded by the social satire of Will Wizard and Anthony Evergreen in the serialized Salmagundi and then, in 1809, the renowned Dutch pseudo-historian Diedrich Knickerbocker. Pseudonyms were used routinely in political writing: Greek and Latin names were meant to suggest grandeur and credibility on the part of the ostensibly unknown author.

What the brash young Irving did was to attach a comic name to an absurd perspective and show how democracy was becoming unruly and America’s political leaders, hypocritical panderers. “An election is the grand trial of strength,” he wrote in a Salmagundi essay, in which candidates come out in force, bringing along their army of “tatterdemalians, buffoons, dependents, parasites, toad-eaters, scrubs, vagrants, mumpers, ragamuffins, bravoes, and beggars.” Buffeted by these and “puffed up by his bellows-blowing slang-whangers,” the candidate “waves gallantly the banners of faction, and presses forward TO OFFICE AND IMMORTALITY!”

Though his older brothers were Burrites and then Jeffersonians, Irving was a moderate Federalist in his critical commentary, until joining his brothers in support of Madison and a new nationalism when the War of 1812 began. Irving went on to become an unofficial aide to Andrew Jackson, much in the way other former Federalists did—even Alexander Hamilton’s son, who was a neighbor of Irving’s on the banks of the Hudson, and whose son was a favorite of Irving’s and his top aide when Irving was America’s ambassador to Spain in the 1840s. As a Jacksonian Democrat, Irving promoted a Jacksonian vision of the West; in A Tour on the Prairies (1835) and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville (1837), he painted chivalric portraits of earthy army rangers and fur trappers, and in a slight twist from Horace Greeley’s more quotable “Go west, young man,” Irving asserted that young American men should turn away from the European grand tour and mark their passage to manhood on the western prairies.

Refusing drafts to serve as New York City mayor or run for Congress (“I would have to run mad first”), Irving ended his writing career in the 1850s with a worshipful five-volume biography of George Washington and a final return to the moderate Federalism of his young adulthood. He is only remembered as the genial author of romantic short stories, which is why I decided to incorporate into my biography of him the curious, winding political path he traveled.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein—former coholders of the Mary Frances Barnard Chair in Nineteenth-Century U.S. History at the University of Tulsa and now professor of history and Manship Professor of History, respectively, at Louisiana State University—are presently coauthoring a book on Madison, Jefferson, and the conduct of politics in postrevolutionary America. Individually, they recently completed biographies of historical actors from further north whose reputations have been badly distorted by historians and political enemies alike. Isenberg’s Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr (2007) demonstrates how Burr’s historical reputation has been shaped by his political enemies without consideration of his Enlightenment political ideas and open-mindedness, which appealed to a host of New Yorkers and others. Burstein’s The Original Knickerbocker: The Life of Washington Irving (2007), the first substantial biography of the New York author since 1935 and the first by a historian, situates Irving in Burr-era politics and shows that he achieved his height as a writer not in the way most believe, as a benign romantic, but as a political satirist, lampooning Thomas Jefferson.