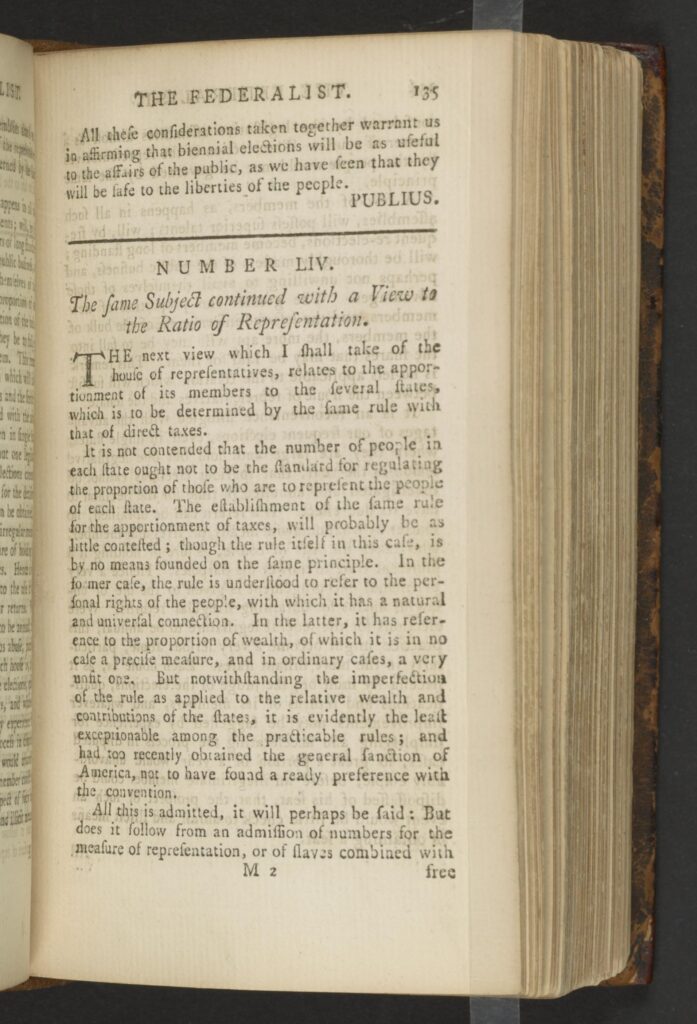

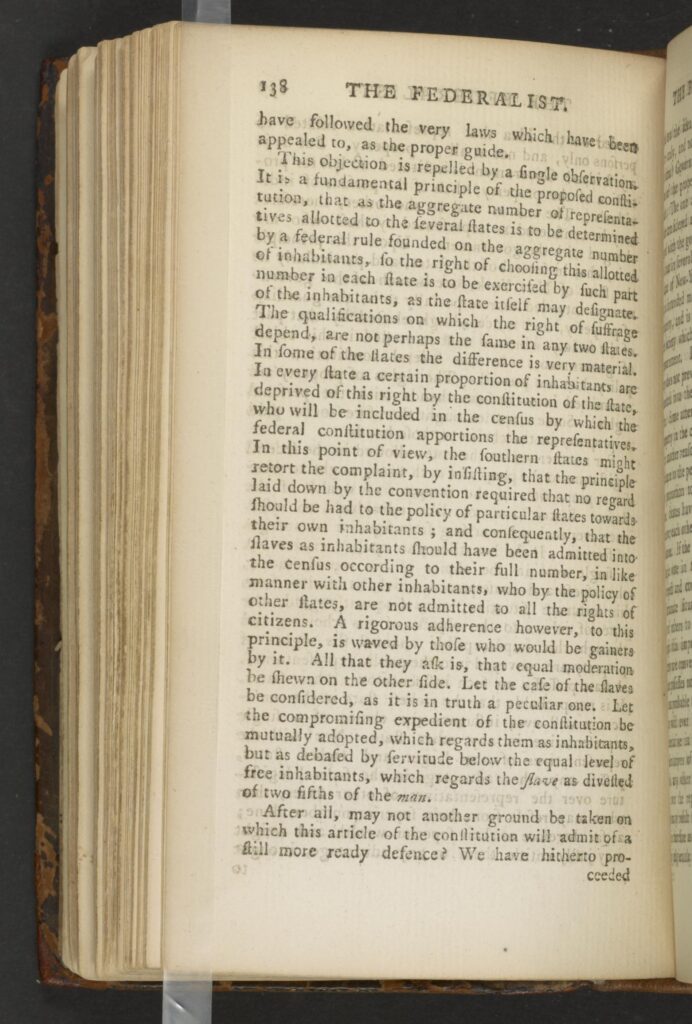

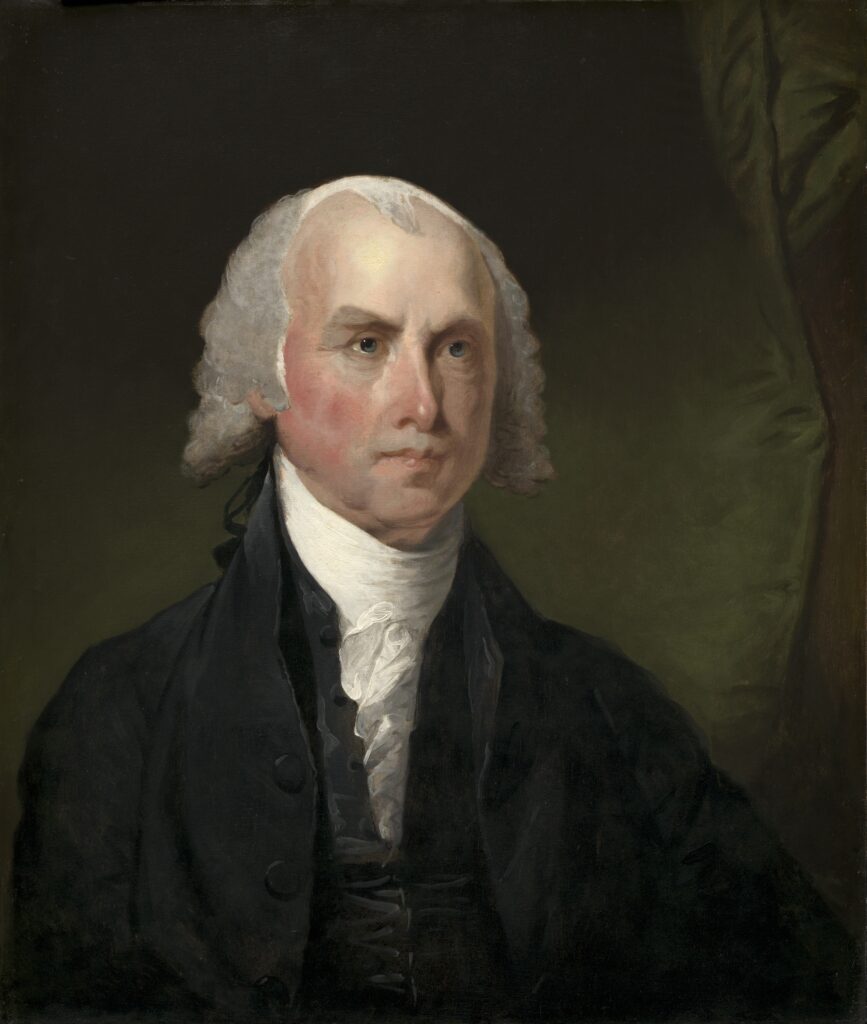

Madison admitted that this benefited Southern states. But Northerners could not have it both ways. They could not count the enslaved “in some degree as men, when burdens were to be imposed,” but omit them from the apportionment tally by arguing they were strictly property. They could not “reproach the southern States with the barbarous policy of considering as property a part of their human brethren” and then turn around and “contend that the government to which all the States are to be parties, ought to consider this unfortunate race more compleately in the unnatural light of property, than the very laws of which they complain!” The Constitution already counted “other inhabitants” (like white women and children, though Madison did not list these examples specifically) on a one-to-one basis with free white men. By this measure, Madison suggested, counting three-fifths of the enslaved population was something of a bargain for the North. Would Northerners prefer all slaves counted toward apportionment?

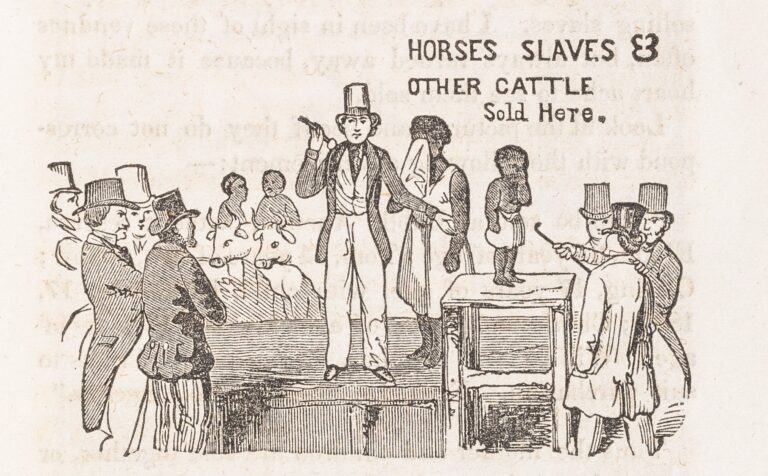

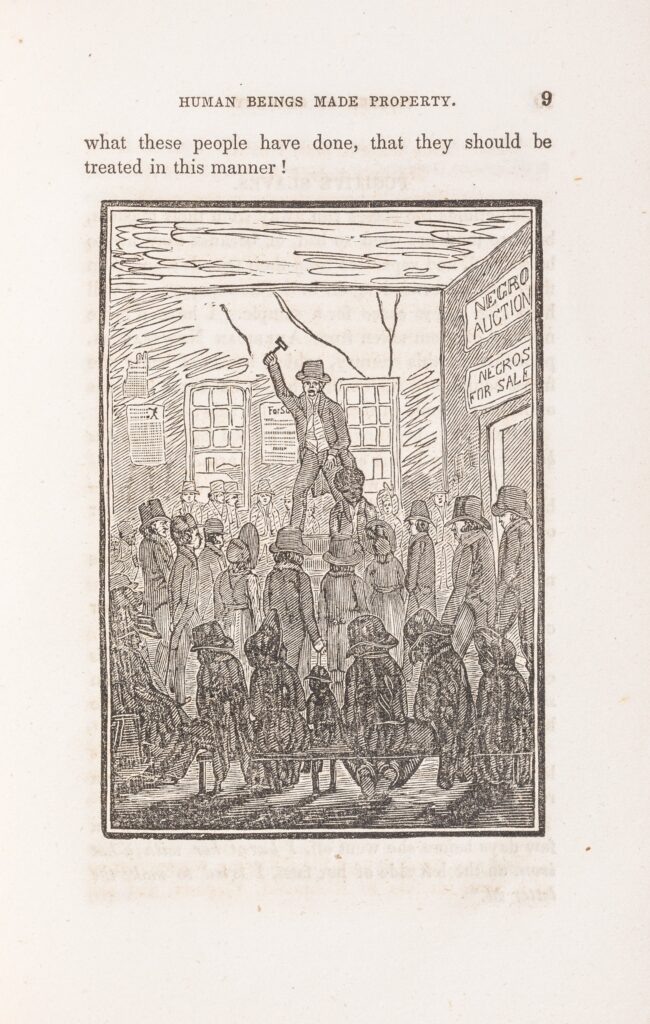

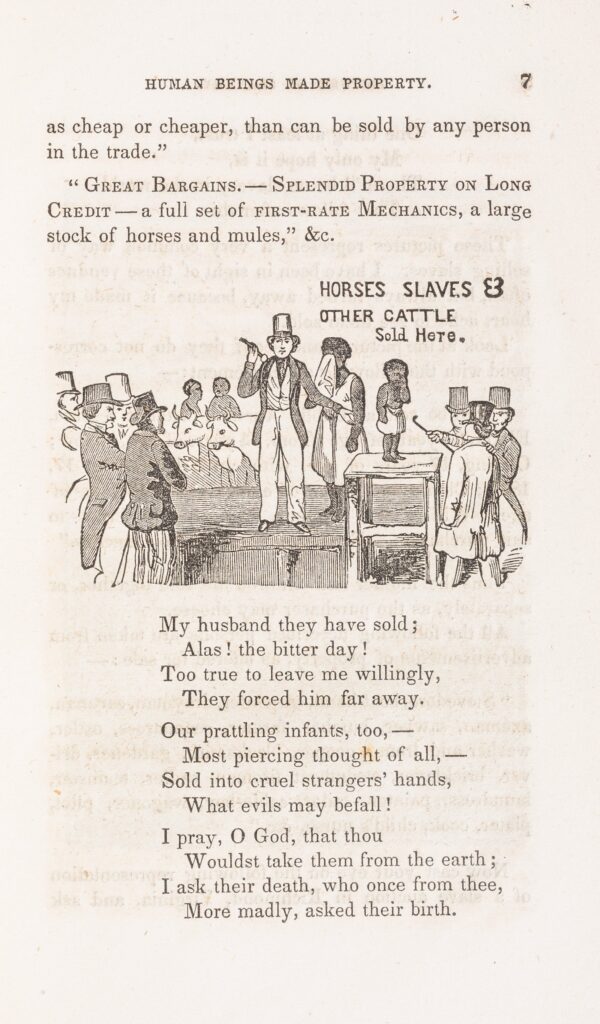

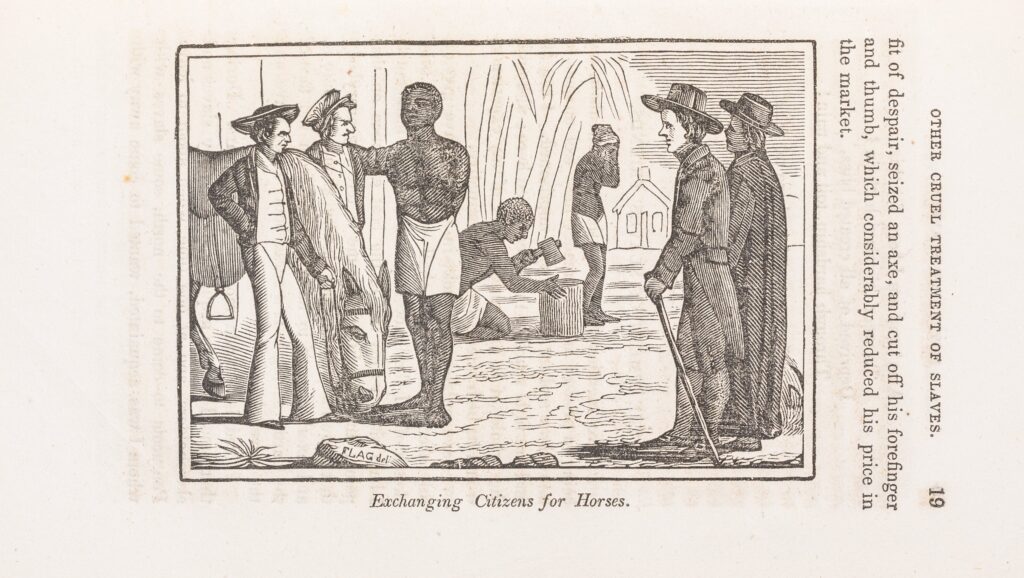

For Madison, as for other defenders of the three-fifths clause, an enslaved person was not “three-fifths of a person” because they were their master’s property any more than they were only “three-fifths” the property of their master because they were a person. It should be obvious that none of this makes slavery more “humane.” It means that the Constitution gave enslavers a vested interest in acknowledging that the people they claimed as “property” were people. The three-fifths clause allowed enslavers to exploit the humanity of people they enslaved, to use the fact of their personhood, for political gain. Whether defending or criticizing the three-fifths clause, participants in the public ratification debate were convinced that how the Constitution treated enslaved people—as “property” and as “persons”—would be the key to the future of slavery, Southern power, and racial hierarchy.

Further Reading

Primary sources related to the three-fifths clause and the ratification of the Constitution may be found in:

The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution Digital Edition, ed. John P. Kaminski, Gaspare J. Saladino, Richard Leffler, Charles H. Schoenleber, and Margaret A. Hogan (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009).

Secondary sources:

Mary Sarah Bilder, Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017).

Robin Einhorn, American Taxation, American Slavery (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Jan Ellen Lewis, “The Three-Fifths Clause and the Origins of Sectionalism,” in Barry Bienstock, Annette Gordon-Reed, and Peter S. Onuf, eds., Family, Slavery, and Love in the Early American Republic: The Essays of Jan Ellen Lewis (Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press, 2021), 254-80.

Jan Ellen Lewis, “What Happened to the Three-Fifths Clause: The Relationship Between Women and Slaves in Constitutional Thought,” Journal of the Early Republic 37 (Spring 2017): 1-46.

Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Matthew Mason, Slavery & Politics in the Early American Republic (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

David Waldstreicher, Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification (New York: Hill and Wang, 2009).

Sean Wilentz, No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Christopher D. E. Willoughby, Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

This article originally appeared in September 2024.

Nathaniel C. Green is Professor of History at Northern Virginia Community College. A specialist in early U.S. political culture, he is the author of The Man of the People: Political Dissent and the Making of the American Presidency (University Press of Kansas, 2020; paperback, 2024). He is currently at work on a book-length study of the three-fifths clause, tentatively titled Three Fifths: The Constitution, Slavery, and the Toxic Politics of Compromise.