“Now I Chant Old Age”: Whitman’s Geriatric Vistas

“Youth, large, lusty, loving—youth full of grace, force, fascination,/

Do you know that Old Age may come after you with equal grace, force, fascination?”[1]

When you think of Walt Whitman, you likely imagine him in one of two flamboyant performances of age: either striking his proletariat pose as “one of the roughs,” youthful and ruddy, or as the “good gray poet,” wizened, seated, and a bit disheveled. With these two strategic images of his aging body, Whitman aimed to condition readings of his works, and they have continued to shape our understanding of his career as a poet and public figure. But these iconic personas of youth and old age also direct us to consider the treatment of age in Whitman’s oeuvre and to reflect on how his own aging and debility register in his work, inspiring and constraining the scope of his poetic imagination (fig. 1).

Some of the best-known lines from Leaves of Grass invoke age as a way of gesturing to the poet’s fantasy of inhabiting the subjectivities and bodies of all Americans. That is, Whitman recognized age as an important category of difference but also one that he believed he could transgress through poetry, at least in 1855. Consider these well-known lines from “Song of Myself”:

I am of old and young, of the foolish as much as the wise,

Regardless of others, ever regardful of others,

Maternal as well as paternal, a child as well as a man,

Stuffed with the stuff that is coarse, and stuffed with the stuff that is fine.

Here and elsewhere in the poem, Whitman imaginatively inhabits the bodies of children and adults, setting up old and young as consequential and opposing statuses. Later, he adopts the persona of a grandmother: “It is my face yellow and wrinkled instead of the old woman’s,/ I sit low in a strawbottom chair and carefully darn my grandson’s stockings.” Whitman imaginatively assumes her habitus, claiming her body as his own. And in “Song of Joys,” he again ventriloquizes an elderly woman: “I am more than eighty years of age, I am the most venerable mother.” That he specifically calls attention to the bodies of old women might suggest an attunement to the marginalized or discounted members of society. But Whitman’s use of age in 1855 is no more progressive than his engagement with other subordinated subject positions; instead, age categories offer a figurative avenue for Whitman to signal his capacious democratic sensibility and his psychic mobility. Along with class, race, and gender, Whitman relies on age as a performative site of his imagined embodiments and as a strategy for enacting his universalizing project.

But how did Whitman experience his own aging? What did it mean for him to become old, to inhabit an aging body, not merely to imagine it? Over the last few decades, critics have devoted increasing attention to Whitman’s later work, acknowledging it as an overlooked aspect of his oeuvre and theorizing its neglect.[2] For example, Elizabeth Lorang points to “the prevailing assumption … that Whitman in old age is neither as interesting nor as radical as the poet of the 1855 Leaves of Grass.”[3] And Anton Vander Zee observes that it has now “become common… to note that Whitman’s late work has been unjustly overlooked and neglected.”[4]

Whitman criticism tends not only to discount his later work, as these scholars acknowledge, but it also overlooks how the poet himself engages with age as a trope, as an analytic, and as a politically significant category of identity.[5] Indeed, the prodigious new volume Walt Whitman in Context includes virtually every possible lens for reading the poet with the exception of age, despite its importance in his work, his career and persona, as well as its heightening ideological prominence in the culture at large during his lifetime. Attending to a portion of Whitman’s later work, primarily his 1888 newspaper poetry, this essay shows how his old-age poetry exploits—and violates—cultural scripts for late life, as they emerged at the end of the nineteenth century.

As with any life, it is difficult to know when Whitman’s old age begins. After all, “old age” is a constructed category that tends to recede as one grows older; that is, even while aging is a biological reality, the stages of life are culturally produced categories, shaped by demographic, economic, and social conditions. With Whitman, we might mark the onset of his old age to 1873 when he suffered the first of several strokes. Or we could see the commencement of this phase of his life with Specimen Days, and Collect (1882), his war and disability memoir, which Lindsay Tuggle calls “the largest and arguably most significant work of Whitman’s old age.”[6] Or perhaps Whitman’s old age begins in 1884, at which time he moved into the house on Mickle Street in Camden, New Jersey, supported by a rotating cast of caregivers and housekeepers.

Given the fact that old age is a social status as much as a biological one, we might trace the beginning of Whitman’s old age to his assumption of the persona of the “Good Gray Poet.” As Whitman scholars well know, William Douglas O’Connor coined the sobriquet “Good Gray Poet” in an 1866 pamphlet published to purify and dignify the poet’s reputation after he was expelled from a government job with the Secretary of the Interior because of the perceived indecency of Leaves of Grass the year before (fig. 2). In his impassioned defense of Whitman, O’Connor described the poet with “flowing hair and fleecy beard, both very gray,” observing, “The men and women of America will love to gaze upon the stalwart form of the good gray poet, bending to heal the hurts of their wounded and soothe the souls of their dying.”[7] Significantly, this image invokes Whitman’s experience as a war nurse to cast him in the role of benevolent old man—that is, O’Connor essentially rebrands Whitman through age discourse, relying on the cultural assumption that old age and sexuality are incompatible, even unthinkable, together. In other words, the invention of the “Good Gray Poet” is a tactical deployment of the normative life course, which, in Jane Gallop’s words, “dictates which segments of life are properly sexual and which are not.”[8] Given that Whitman was only forty-six years old in 1866, the construction of this bearded old man is itself a beard to conceal the deviance with which he had become associated.

Whitman entered old age in a period when aging began to signify differently in U.S. culture. While old age was never a purely vaunted status in the U.S., it was more venerable—for white men—in an agrarian economy that looked to older generations as sources of wisdom. With the rise of market capitalism, urbanization, and mass media over the course of the nineteenth century, older people began to occupy a degraded position in the culture. The professionalization of medicine, along with the rise of social science, catalyzed a shift in the way Americans understood and experienced aging. As historian Carole Haber writes, doctors and statisticians alike articulated a view of “senescence as a distinctive and debilitated state of existence.” Indeed, as older people lost their utility to the prevailing economic system, the aging body came to be seen as a sign of failure and a site of revulsion.[9]

We might therefore see the second half of the nineteenth century not only as the era in which institutional care emerged for the aged but also as the era in which ageism itself was institutionalized. The management of elderly people in this period coincides with the regime of surveillance applied to disabled people, which resulted in the “ugly laws” and other strategies to remove “unsightly” and dependent people from public spaces.[10] Consider this 1875 article in Scribner’s: “Is it desirable that all men and women should become centenarians? Manifestly not. These shrunken, shriveled relics of a past age, in the knotted and tangled line of whose life personal identity has barely been preserved, would, if familiar to our eyes, produce a depressing effect on the living.” This piece encapsulates the burgeoning cultural anxiety about old age as a state that challenges “identity” as well as the notion that old age is offensive to “our eyes,” in other words, unpleasant to see. Old people, according to this article, are “depressing” to the “living;” thus, they are not even alive.

Whitman, however, did not acquiesce to this notion of old age as irrelevant or unworthy of attention. On the contrary, he strategically capitalized on the persona of the Good Gray Poet, seizing upon the mutability of age as a discursive resource.[11] In an anonymously published article, “Walt Whitman’s Actual American Position,” which appeared in the West Jersey Press in 1876, Whitman described himself as “old, poor, and paralyzed” but ignored by editors and publishing houses. Indeed, where his earlier self-promotional work cast him as an undiscovered literary ingénue, here Whitman characterizes himself as a poor, feeble, underappreciated old man, who is viewed with “disgust” by the mainstream literary establishment. As he puts it, American publishers and authors have met his poems with “determined denial,” and agents have “taken advantage of the author’s illness.”[12] Whitman’s article draws on the pathos of old-age impoverishment, referring to “bleakness of the situation,” in order to heighten his own celebrity and sales.

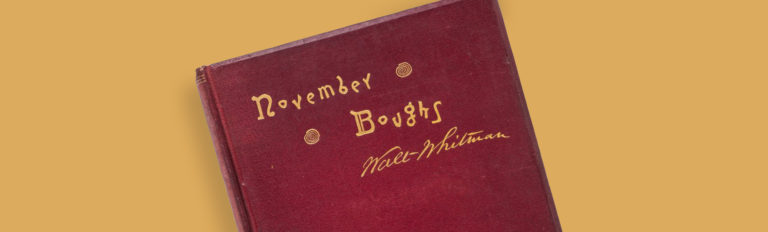

Beyond this savvy management of age discourse for marketing purposes, Whitman meditated frequently on the idea of aging in his poetry. His later work attends to the material effects of aging and complicates the reductive ideas about elderliness that he propagated in self-promotional schemes and that circulated in mainstream culture. With the publication of his essay “A Backward Glance O’er Travel’d Roads” in the 1885 publication of his collected works and November Boughs (1888), the first annex to Leaves of Grass, Whitman took on his own aging as a vital and multivalent subject. This project of documenting old age culminated with his 1891 pamphlet, “Good-Bye My Fancy,” which became the second annex to Leaves of Grass. And beyond this, he left instructions for the publication of his posthumous work to be published in a volume he titled “Old Age Echoes.”

For the remainder of this essay, I turn to a selection of Whitman’s letters and poems from 1888, when he was sixty-nine years old and living on Mickle Street, suffering from a range of chronic conditions, often confined to his bed. For a writer who devoted much of his life to journalism, it is perhaps unsurprising that he continued to read and publish in newspapers as he grew increasingly house-bound, often bed-bound. As Ingrid Satelmajer notes, “Characterizations of Whitman in his final years at Camden depict the poet nearly buried as he read the tide of newspapers and magazines regularly delivered to him”[13] (fig. 3).

Until the end of his life, Whitman remained an avid reader of newspapers as well as a prolific contributor. In 1888 alone, he published thirty-three poems in the New York Herald; these poems would ultimately appear together in November Boughs (1888). While the Herald originated as a sensational penny paper in the 1830s, it retained its focus on short pieces and amusements in the latter part of the century. Amid trivial gossip and entertainment news, Whitman’s poems on graves and dismantled ships and dead emperors stand out as an odd fit for the paper’s front page and its tone of levity and impersonality. Reading these public poems alongside Whitman’s correspondence with friends and relatives during this same year introduces a range of questions: What is the relationship between his declining health and his prolific output? How can we interpret his decision to publish in the Herald during a time when he was grappling with immobility and chronic pain? (fig. 4)

Whitman’s 1888 letters offer a starting point for thinking about how experiences of aging and disability shaped his poetry. The letters share a set of conventions, constituting a kind of genre unto themselves. Without fail, Whitman comments on his health (often noting the state of his bowels), reports the weather, and describes his meals, noting that he often only eats twice per day. (Some of his favorite foods are “corned beef & mince pie,” “chocolate & buckwheat cakes,” and Graham bread.) Whether he is writing to O’Connor, William Kennedy, or Jerome Buck, there is little variation in these letters; a characteristic line is: “All goes as well & monotonously as usual (No news is good news).”

In light of his own repeated claims to having “no news,” Whitman’s relationship with the Herald provided a way of remaining ambulatory, relevant, and in circulation. As he explained to Herbert Gilchrist: “I AM more disabled perhaps in locomotion power & in more liability to head & stomach troubles & easiness of ‘catching cold’ (from my compulsory staying in I suppose)…. I am writing little poetical bits for the N Y Herald.” Here, he pairs his lament about his loss of “locomotion power” with his report about publishing in the Herald, setting up a link between his “compulsory staying in” and his desire to send “poetical bits” out into the world. Juxtaposed with the reference to his stomach troubles, the phrase “poetical bits” invokes waste, excretions, or half-digested food. Read this way, Whitman is repurposing his waste by publishing it and sending it into circulation, echoing the regeneration cycle he describes in “Song of Myself,” in which grass operates as a metonym for the interconnectedness of all things. The ephemeral nature of newspapers reinforces this notion of poetry as embedded in a cyclical process.

Whitman similarly positions the newspaper as a vehicle for mobility and sustenance in his letter to John Burroughs in April 1888. “With me things move on much the same—a little feebler every successive season & deeper inertia—brain power apparently very little affected, & emotional power not at all—I yet write a little for the Herald.” Here, the Herald serves as a counterbalance to the report about his feebleness, as if his connection to the newspaper is a life-source or evidence of his vitality in spite of his physical incapacities[14] (fig. 5).

Significantly, however, these old-age poems are not the ecstatic encounters with nature or diverse swathes of humanity with which we typically associate Whitman. On the contrary, most of these newspaper poems are meditations on aging and offer unsentimental reflections on the later stages of life. Given their appearance in the pages of a mainstream newspaper, Whitman’s poetry enacts a disruptive function, forcing readers to confront his aging and ailing amidst coverage of the weather, short discussions of home remedies, and bits of humor. Whitman, in other words, makes his own aging front-page news, disrupting the socialized invisibility of elderly people[15] (fig. 6).

These late-life poems demand an alternative way of reading Whitman’s relationship to the body and to poetry itself; to borrow Simone de Beauvoir’s words, they describe the “body as a situation,” as a cultural text as much as a biological fact.[16] Whitman, in other words, inhabits not merely the materiality of his body but also its significance in a social order that attaches rigid meanings to disability, elderliness, and illness. In “As I Sit Writing Here,” Whitman reflects on the disciplinary work of aging scripts, acknowledging that one is not supposed to write about bodily decrepitude:

As I sit writing here, sick and grown old,

Not my least burden is that dulness of the years, querilities,

Ungracious glooms, aches, lethargy, constipation, whimpering ennui,

May filter in my daily songs.

Whitman worries here that his “aches” and “constipation” will intrude into his “daily songs.” Of course, the irony of the poem is that it is fundamentally about those “ungracious glooms,” about the inseparability of one’s body from one’s poetic imagination and creative work. His “burden” then is not merely the monotony of his days or his indigestion but the expectation to keep one’s ailing body out of the public sphere and to silence the “whimpering ennui.” Whitman’s lament that his poetry will bear the marks of his sickness and age locates him within a cultural moment that scrupulously monitored which bodies could appear in public and sought to “repress the visibility of human diversity” through a range of legal, medical, and social tactics.[17]

In spite of the critical tendency to read Whitman’s treatment of the body as utopianizing, invincible, erotic, and transcendent, Whitman’s later poetry suggests embodiment might also be intransigent and restrictive. Indeed, Benjamin Lee makes the incisive point that when we think of Whitman as the “poet of the body,” we only think through the Civil War, but we need to extend that consideration through his old age. These late-life poems suggest a development in Whitman’s attitude toward the body and aging, a turn in his theorization of embodiment. If, in 1855, he whimsically wrote of being a widow, darning socks for grandchildren, Whitman in 1888 has come to a different perception of the body. These old-age poems align with Edward Said’s definition of “late style” as that which “involves a nonharmonious, nonserene tension.”[18] No longer does poetry serve as a device for assuming other selves; the elderly body cannot be evaded.

This shift in Whitman’s scope and sensibility is also palpable in “A Carol Closing Sixty-Nine,” which meditates on his chronological age and aging body in relation to the landscape of the nation. The poem begins by looking outward, with a familiar nationalist imagery of the “rivers, prairies, States,” but as it progresses, the poem tightens, moving inward to the body. From the “mottled Flag,” Whitman turns to his “jocund heart” and his “body wreck’d, old, poor and paralyzed.” Where in “As I Sit Writing Here,” Whitman worries that his bodily ailments will bleed into his poems, “A Carol Closing Sixty-Nine” enacts that usurpation. Whitman’s lofty patriotism is interrupted by his material existence:

A carol closing sixty-nine—a résumé—a repetition,

My lines in joy and hope continuing on the same,

Of ye, O God, Life, Nature, Freedom, Poetry;

Of you, my Land—your rivers, prairies, States—you, mottled Flag I love,

Your aggregate retain’d entire—Of north, south,

east and west, your items all;

Of me myself—the jocund heart yet beating in my breast,

The body wreck’d, old, poor and paralyzed—

the strange inertia falling pall-like round me;

The burning fires down in my sluggish blood not yet extinct,

The undiminish’d faith—the groups of loving friends.

Even as his body is “old” and “wreck’d,” Whitman refers to the “burning fires down in [his] sluggish blood,” suggesting his capacity for arousal and physical pleasure. These “not yet extinct” fires in his blood and the “heart yet beating” are linked to his “groups of loving friends,” which affirm the potential for intimacy to co-exist with paralysis and old age. The poem ultimately becomes an occasion for Whitman to reflect on the “strange inertia” of his life—the odd stillness and monotony that defines his existence even while his heart beats and his blood flows. His body in this poem is at once sluggish and fiery, vigorous and paralyzed, a reminder that old age does not cancel sensation even as it might compromise mobility.

Encountering Whitman’s meditations of his “wreck’d” body in the Herald impels readers to contemplate the realities of old age and to encounter the iconic Whitman anew. While Stauffer claims that Whitman was “determined to keep as much as possible of his own sickness and pain out of his poems,” on the contrary, we can see these poems as a public engagement with physical decline and the frustrations of inactivity that often characterize the end of life as well as with the unpredictable, inarticulable longings and affective experiences of old age.[19]

While Whitman’s longtime assistant and friend Horace Traubel and others saw the approach of his seventieth birthday as an occasion to fete the poet, Whitman saw it as the subject for introspection and reflection. Take, for instance, “Queries to My Seventieth Year,” in which he wonders whether turning seventy will signify “strength, weakness, blindness, more paralysis.” He refers to himself as “dull, parrot-like and old with crack’d voice harping, screeching”—suggesting the extent to which his physical ailments affect his voice, both his literal speaking voice and his poetic voice. He worries about being repetitive (“parrot-like”) and whiny.

Still, it would be a mistake to see only grimness and suffering in Whitman’s old age and the work he produced in his last decade. His 1891 poem “On, on the same, Ye Jocund Twain!” is less somber, even cheerful with its exclamation point. Over the course of the poem, he announces himself as chanting the nation, the “common bulk,” and lastly, “old age”—a progression that moves from the abstract to the intimate, from the general to the particular. Whitman explains that he once wrote “for the forenoon life . . . but [now] I pass to snow-white hairs the same, and give to pulses winter-cool’d the same.” In other words, he sees himself now as writing on behalf of and for older readers, to the “unknown songs, conditions” that comprise the latter phases of life.

An attention to the full range of Whitman’s poetic output helps us to see him as a theorist of the aging body. As he explains in “A Backward Glance O’er Travel’d Roads,” “Leaves of Grass has mainly been the outcropping of my own emotional and other personal nature—an attempt, from first to last, to put a Person, a human being (myself, in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, in America,) freely, fully and truly on record.” The perpetual expansion of Leaves of Grass suggests his vision of the self as variegated and discontinuous. The clusters he calls “annexes” are poetic extensions that thematize his sense of the self as inherently unfinished and open-ended, which continue to accumulate in old age. As Amelia DeFalco writes, “Aging involves perpetual transformation that unsettles any claim to secure identity, allowing strange newness to intrude into a subject’s vision of a familiar self, and undermining efforts to construct coherent life reviews.”[20] In the ongoing annexation of Leaves, Whitman insists on this impossibility, and perhaps the undesirability, of completing the self.

Though it has been tempting for critics to read Whitman as resistant to the association of aging with decline, these later poems reveal his struggle with debility, dependence, and loss as a central preoccupation of his old age. As he told Traubel, “Some day you will be writing about me: be sure to write about me honest: whatever you do, do not prettify me: include all the hells and damns.” Indeed, in a cultural moment that began to repress discussions of aging, conceal aging bodies, and pathologize growing older, Whitman’s poetic dispatches from what he called the “palsied old shorn and shell-fish condition of me” offer an unapologetic candor about the experience of elderliness.

Whitman is far from the only major author whose old-age work has been deemed unworthy of serious attention. Women writers in general are rarely considered in the context of their “late” careers, as the concept tends only to apply to male artists and authors for whom maturation is akin to improvement and refinement.[21] And in the case of some writers, the late work necessarily complicates or even undermines a coherent or stable sense of their oeuvre, making it more desirable simply to avoid it.[22] Christopher Hanlon has recently observed a “tendency to sublimate the very facts of Emerson’s senescence,” noting a scholarly reticence to engage with Emerson’s senility as it proves incompatible with the more appealing image of self-reliant individualism for which he is known.

Interestingly, Whitman’s aging was spectacularized in the press, analyzed in his own poetry, and celebrated in massive public birthday parties; this was not a figure who receded or retired from public life as he grew older (fig. 7). And yet there is a tendency to read Whitman only in relation to the celebrated antebellum work that sets up a vision of the body as limitless, a kind of material analogue to Emerson’s “transcendent eyeball” even as his late-life poems focus heavily on his own lived experience in his ailing body. Whitman himself saw those years as equally essential, poetically viable, even newsworthy. Of “Sands at Seventy,” a collection of poems that appeared in November Boughs, he wrote:

The Sands have to be taken as the utterances of an old man—a very old man. I desire that they may be interpreted as confirmations, not denials, of the work that has preceded . . . I recognize, have always recognized, the importance of the lusty, strong-limbed, big-bodied American of the Leaves: I do not abate one atom of that belief now, today. But I hold to something more than that, too, and claim a full, not a partial, judgment upon my work—I am not to be known as a piece of something but as a totality.

Whitman clearly understood this late work as of a piece with his earlier work; that is, the “lusty, strong-limbed, big-bodied American” is inseparable from the “very old man” that appears in the poems of the 1880s. His description of himself as a “totality” is an articulation of a desire to be read not only as the voice of vigorous, young manhood but also of illness and debility, an insistence that future readers acknowledge him in relation to a broad spectrum of age identities, embodied and enacted.[23]

Most readers are familiar with Whitman “at the beginning of a great career,” but his work and perspective at the end of that career warrant just as much attention. In “The Final Lilt of Songs” (1888), Whitman refers to “old age” as the “entrance price” to a real understanding of literature and art; it is the “last keen faculty” that allows one to “penetrate the inmost lore of poets.” Far from signaling the diminution of interpretive ability or affective capacity, old age here is linked to critical acumen. As readers of Whitman, we must likewise attend to his old age as both material reality and performative accomplishment in order to “get at the meaning of [his] poems.”

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Don James McLaughlin, Clare Mullaney, Cecily Parks, and Holly Jackson for their insightful feedback on this essay and to Jackie Penny for her help with the images.

________________

[1] Walt Whitman, Complete Poetry and Collected Prose, ed. Justin Kaplan (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1982): 249.

[2] Donald Barlow Stauffer observed that Whitman’s later work has been “dismissed too lightly.” Similarly, Benjamin Lee writes: “It seems remarkable that his late poetry has inspired so little interest.” Lee, “Whitman’s Aging Body.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 17 (Summer 1999): 38-45.

[3] Elizabeth Lorang, “‘Two more throws against oblivion’: Walt Whitman and the New York Herald in 1888.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 25.4 (Spring 2008): 167–191.

[4] Anton Vander Zee, “Inventing Late Whitman.” ESQ – Journal of the American Renaissance 63:4 (Jan. 2017): 641-680. Vander Zee offers an excellent comprehensive assessment of the critical reception of Whitman’s old-age work.

[5] Several important studies have engaged with Whitman vis a vis death; see especially Harold Aspiz and Adam Bradford.

[6] Lindsay Tuggle, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning, and Whitman’s Civil War (Des Moines: University of Iowa Press): 14.

[7] William Douglass O’Connor. “The Good Gray Poet.”

[8] Gallop, Sexuality, Disability, and Aging: Queer Temporalities of the Phallus (Durham: Duke UP, 2019): 8.

[9] Jane Gallop observes that “in the current moment, the worship of the reproductive future might in fact devalue old people even more than it does queers.” Gallop, Sexuality, Disability, and Aging: Queer Temporalities of the Phallus (Durham: Duke UP, 2019): 11.

[10] Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: NYU UP, 2000): 3.

[11] I am grateful to Don James McLaughlin for this formulation and for bringing “Whitman’s Actual American Position” to my attention.

[12] Reynolds refers to this piece as “shameless” and as “grossly untrue factually” even while he acknowledges the success of this article in heightening Whitman’s celebrity. Indeed, Reynolds essentially describes Whitman as senile, noting that “he began to get more requests for periodical contributions than his old brain could handle.” Reynolds, Walt Whitman’s America (515).

[13] Ingrid Satelmajer, “Periodical Poetry.” Walt Whitman in Context. Eds. Joanna Levin and Edward Whitley (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2018): 69. This “tide” of newspapers connects Whitman to many well-known “hoarders,” or people who accumulate in excess as they age, suggesting that old age is a status that is often at odds with capitalism and the relation to consumption it defines as normative. See Scott Herring, The Hoarders: Material Deviance in Modern American Culture (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2014).

[14] As Elizabeth Lorang writes of Whitman’s newspaper poetry, it serves to alert the “public of his still being alive.” Lorang, “‘Two more throws against oblivion’: Walt Whitman and the New York Herald in 1888.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 25.4 (Spring 2008): 167–191.

[15] Of the changing social status of aging people in the late nineteenth-century U.S., historian Carole Haber writes, “Mandatory retirement, pension plans, geriatric medicine, and old-age homes were not designed to reintegrate the elderly into the culture… Rather, these programs ensured the separation of the old from work, wealth, and family.” Haber, Beyond Sixty-Five: The Dilemma of Old Age in America’s Past (5).

[16] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage, 2011): 46.

[17] See Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: NYU UP, 2000): 3.

[18] Edward Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Knopf, 2006). Said further defines “lateness” in terms of a “vulnerable maturity, a platform for alternative and unregulated modes of subjectivity.”

[19] Donald Barlow Stauffer, “Age and Aging.” J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings, eds., Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998).

[20] Amelia DeFalco, Uncanny Subjects: Aging in Contemporary Narrative (Columbia: Ohio State UP, 2010): 22.

[21] For a discussion of the gender politics of aging in American literature, see Sari Edelstein, Adulthood and Other Fictions: American Literature and the Unmaking of Age (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[22] Indeed, Edward Said, drawing from Theodor Adorno, defines “late style” as the “moment when the artist who is fully in command of his medium nevertheless abandons communication with the established social order of which he is a part and achieves a contradictory, alienated relationship with it.” Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Random House, 2006): 8.

[23] Whitman articulated the same viewpoint in relation to Emerson: “The senile Emerson is the old Emerson in all that goes to make Emerson notable: this shadow is a part of him—a necessary feature of his nearly rounded life: it gives him a statuesqueness—throws him, so it seems to me, impressively as a definite figure in a background of mist.” Walt Whitman in Camden, March 28, 1888.

Further Reading

On the cultural history of old age in the U.S., see Carole Haber, Beyond Sixty-Five: The Dilemma of Old Age in America’s Past (New York, 1985) and Old Age and the Search for Security: An American Social History, Eds. Carole Haber and Brian Gratton (Bloomington, Ind., 1993). See also W. Andrew Achenbaum’s Old Age in the New Land: The American Experience since 1790 (Baltimore, 1980), David Hackett Fischer’s Growing Old in America (Oxford, 1978), and Thomas Cole, The Journey of Life: A Cultural History of Aging (New York, 1992). On Whitman and aging, see Benjamin Lee, “Whitman’s Aging Body.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 17 (Summer 1999): 38-45, Anton Vander Zee, “Inventing Late Whitman.” ESQ: Journal of the American Renaissance 63.4 (Jan 2017): 641-680, Donald Barlow Stauffer, “Walt Whitman and Old Age.” Walt Whitman Review 24 (1976): 142–148, and especially Intimate with Walt: Selections from Whitman’s Conversations with Horace Traubel, 1882-1892. Ed. Gary Schmidgall (Des Moines, 1970). On the notion of “late” work, see Edward Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York, 2007), Kathleen Woodward, At Last, the Real Distinguished Thing: The Late Poems of Eliot, Pound, Stevens, and Williams (Columbus, Ohio, 1980), and Linda Hutcheon and Michael Hutcheon, “Late Style(s): The Ageism of the Singular.” Occasion 4 (2012).

www.whitmanbicentennialessays.com

This article originally appeared in issue 19.1 (Spring, 2019).

About the Author

Sari Edelstein is associate professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. She is the author of Between the Novel and the News: The Emergence of American Women’s Writing (2014) and Adulthood and Other Fictions: American Literature and the Unmaking of Age (2019).