…And Now For Something Completely Similar

Since the doleful events of September 11, one of the points made by almost everyone, from the president to television commentators to the freshmen in my survey class, has been the radical newness of the era in which we now find ourselves. “Four Days That Transformed a President, a Presidency and a Nation, for All Time,” ran one New York Times headline, by no means the most hyperbolic of the past two weeks. There is no denying that we all have been changed to some degree by what one hopes will stand for a long, long time as the deadliest single day for Americans outside of a battlefield. And few American battlefields have ever come close. Though most other nations have had their cities attacked in the twentieth century–if not destroyed, invaded, or occupied–the United States has seen nothing like this since the Civil War. If foreign attack is the standard, then the last occasion can be pushed back to the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815, in which we lost exactly eight men. Perhaps most importantly, all the close rivals of September 11 in our history involved solder and sailors, who at least knew that they faced death, not office workers and airline passengers in peacetime who by rights should have been more concerned with where they were going to have lunch than whether they would survive the day.

The recent events are new to us, then, if not to the people of London or Paris or Berlin or Tel Aviv or Hiroshima. The last decade has been an era when many people seemed to feel that nothing “real” had ever happened to them, nothing that tested their limits and characters. Suffused with a somewhat facile sense of the insubstantiality of modern life (and politics), middle-class people seemed to yearn for experiences more intense than what their suburban lives provided. Bourgeois anomie is an old story, but it seemed particularly virulent in the 1990s. Vast audiences sought out extreme experiences as entertainment–from slasher movies, to first-person-shooter video games, to thrill rides, to so-called “reality” television, to popular military history. Until last month, there was even a transportation disaster-themed restaurant, The Crash Café, being planned for Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. At the same time, there was a bull market not just on Wall Street, but in evangelical religion and other forms of spirituality and self-help, all promising to connect believers to a realer reality than anything we have down here.

In a bewildering variety of ways, Americans sought to find and identify with something authentic and serious in their own personal histories, from a childhood trauma to a psychological syndrome to an ethnic heritage to a record of wartime heroism and 1960s activism. Occasionally these bits of personal reality were invented or exaggerated, sometimes by historians, but even the scrupulously honest among authenticity-free Americans had the vicarious option. So baby boomers and their children embraced a burgeoning cult of their World War II era forbears, a cult that was just gearing up for another round of Greatness, related to the HBO series “Band of Brothers,” when the terrorists struck. And for political guidance, at least during this past summer when David McCullough pushed crotchety little John Adams to the top of the charts and Joseph Ellis continued to attract huge audiences for tales of the founding fraternity, we were supposed to look all the way back to the “Even Greater Generation,” the Founders.

Now something real really has happened, not to one of the great generations, but to us. And it is almost unbearable. With a political language devalued by decades of politicians declaring “wars” on every problem of the moment except those requiring military action, there is no available hyperbole that can contain our feelings in the face of such a tragedy, though most of them have been tried. But has September 11 really changed us forever? Has the nation set off down a fundamentally new and different path?

Many early indications suggest not. While President Bush’s spokesmen have mercifully eschewed the bombing-only tactics pioneered by Nixon and Kissinger (and pursued so frequently by Bush père and Clinton), their “new war” sounds suspiciously like most of the other ones since World War II: premised on vague but expansive abdications of congressional authority to the executive branch, and launched with little suggestion that the populace will be required to mobilize or sacrifice for the cause. The new war may go on for years, the administration says, and we might not be told much about it, and it will sometimes be dirty, but we can count on its not affecting us too much, since it will be conducted mostly through precision strikes, “special operations,” and commando raids. Ironically, “war” seems to be the chosen term this time around, not because war will actually be declared or a fundamentally new approach taken, but because all the older euphemisms (“police action,” “conflict,” etc.) lost their magic in previous postwar stalemates and defeats. The American people are aware of the quagmires and disappointments that this nonwar warpath has led us into before–and in the Cold War conflicts we at least had the benefit of knowing pretty clearly who and how we were to fight.

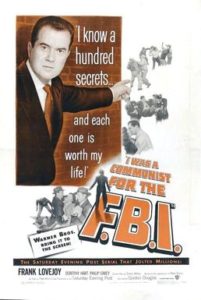

Nor is the same old “new war” plan the only depressingly familiar aspect of the present situation. The warnings that began on the very day of the attack–injunctions that Americans would have to give up some of their freedoms and forgo some democratic niceties in order to combat the threat–have an American history predating the United States itself. Faced with unruly Boston tax protesters in 1768, Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson advised his superiors that there would have to be “an abridgement of what is called English liberty” if the colonies were to remain part of the British Empire. Thirty years later, it was the prospect of war with France–and fear of revolutionists and French sympathizers at home–that had influential figures not just calling for but actually achieving such abridgements, in the form of the Alien and Sedition Acts. (The French Jacobins were the very first modern “terrorists,” of course, though they favored the state-sponsored variety. And while Robespierre probably could have given Osama bin Laden a run for his money, Vice President Thomas Jefferson was considered the likely American terrorist mastermind of that era.) Mobs did most of the wartime liberty abridging during the nineteenth century, but the early decades of the twentieth proved to be something of a golden age for the official variety in America. Faced with seemingly diabolical threats like communism, anarchism, and the Hun, the U.S. government engaged in periodic spasms of trampling on the rights of citizens and immigrants in the name of internal security, beginning with the post-World War I Red Scare that led to mass arrests and deportations and the creation of the FBI. In asking for broader powers to detain suspected terrorists without trial and to conduct electronic surveillance, John Ashcroft’s Justice Department is only returning to the original mission behind its twentieth-century expansion. (Luckily for the country, the usual southern conservative base for crackdowns on the civil liberties of radicals and immigrants seems to be crumbling in Congress this time around.)