Of Indians and Empire

Anglo-American artists began depicting Native Americans soon after their arrival in North America, creating a large body of visual documents that contain varying degrees of truth, fiction, and myth. In Painting Indians and Building Empires in North America, William H. Truettner, senior curator of painting and sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, examines two distinct groups of Native American portraits, which he suggests were each “conceived, directly or indirectly, to accompany attempts to expand white hegemony across North America” (3). The first includes eighteenth-century depictions of Mohawk leaders with whom the crown needed to negotiate in order to maintain access to important colonial holdings in what would become New York State. Truettner sees these images as counterparts to the Noble Savage ideal described by Enlightenment writers and philosophers. The second group of paintings dates to the first half of the nineteenth century and portrays members of the Upper Missouri River tribes, whose cooperation the new Republic depended upon to further fur trapping, exploration, and settlement. Truettner calls this group “Republican Indians,” a term more elastic and less clearly defined than the Noble Savage. He highlights these two groups in order to demonstrate how white observers, in this case, artists, pictured a shift in beliefs about Native Americans, “from one that encouraged the upward mobility of native tribes to one that tied them to the level of human development far below that of white Americans” (5).

Truettner begins his study with an often repeated anecdote about American artist Benjamin West’s first encounter with classical art during his visit to Rome in 1760. Viewing theApollo Belvedere,one of the most celebrated works of the ancient world in the Vatican collection, West reportedly exclaimed, “My God, how like it is to a young Mohawk warrior!” West followed his outburst with a description of the virtues of the Mohawk, suggesting that they might indeed resemble an archaic version of the enlightened Greeks who crafted the Apollo. West characterized the Mohawk as exceptional Indians, gifted with intelligence and superior physical abilities. While this elevation of the Mohawk fulfills an Anglo-American ideal of the Noble Savage, Truettner also suggests that the appeal of the Noble Savage may have been heightened by the British need for Indian allies to serve their imperial ambitions in North America. As Truettner observes, West made his remark at the conclusion of the French and Indian War, during which the British relied on Mohawk allies. In this way, he challenges the belief that the Noble Savage myth was solely a construct of “Rousseauian fables in which ‘savages,’… lived lives of redeeming virtue until they finally (and tragically) came in contact with ‘civilized’ society” (18). Instead, Truettner suggests that to some degree the Noble Savage myth originated in real life interaction between Anglo-American observers and North American Indians. Toward this end, he sees the Mohawk as a special case. The Mohawk both demonstrated idealized Rousseauian virtue and also served an important political purpose for their Anglo-American interpreters.

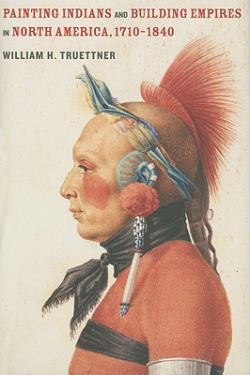

As an art historian, the heart of Truettner’s argument is rooted in the visual. While the first, second, and fourth chapters provide the bulk of his more-textually based historical discussion of Noble Savages and Republican Indians, the lengthier third and fifth chapters provide the visual evidence. For example, in the second chapter Truettner uses first-hand accounts of the Mohawks from Anglo-American observers who characterized the tribe in terms suggestive of the Noble Savage myth. Many of these figures—Cadwallader Colden, James Adair, William Johnson, and Benjamin Franklin—described virtuous Indians using language that evoked the classical past. Additionally, Truettner details how the British specifically cast the Mohawks as Noble Savages in order to serve their imperialist goals in North America. In the third chapter, Truettner discusses a series of portraits of Mohawk leaders, mostly by British artists, which make his case. He begins his study with the John Verelst’s portraits of “four Indian Kings,” who were summoned by Queen Anne to London in 1710. This marks the beginning of what Truettner sees as “portrait diplomacy” by the British. The portraits also initiate the process of turning Indian subjects into denizens of Arcadia through the use of costume, setting, and posture (a tactic that Benjamin West also pursued, most notably in his career-making The Death of General Wolfe.) Truettner includes a useful discussion of six portraits of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant painted by different artists over a span of three decades. Through the Brant portraits Truettner observes “a divide in Indian portraiture at the beginning of the nineteenth century. One trend moves on to picturing ‘civilized’ Indians in European dress … a second and dominant trend leads to a more ethnographic style of imaging, featuring Republican Indians … wearing reasonably authentic attire” (56). Truettner further illustrates the waning of the Noble Savage portrait with an 1828 depiction of Red Jacket by Robert Weir, a work that overlaps chronologically with the rise of the Republican Indian.

The book then shifts to a study of Republican Indians, who hail from tribal groups situated along the Upper Missouri River. Truettner admits that “to claim that Noble Savage portraiture was replaced at a certain time by the next generation of Indian painters, those who created what are here called Republican Indians, is making a neat package of what is essentially a messy, drawn-out transition” (61), and indeed the transition from one type of image to the other is not seamless. According to Truettner, Republican Indian portraiture was initiated in Washington and the east “to service an ambitious, if at first relatively restrained expansionist agenda, begun by Jefferson after the Louisiana Purchase and continued under the administrations of Madison, Monroe, and John Quincy Adams” (70). Republican Indians differ from Noble Savages in significant ways and reflect shifting American perceptions about native peoples. While the Noble Savage might have been an idyllic Arcadian on the verge of civilization, the Republican Indian was widely perceived as doomed to vanish, having no place in a white-populated West and little ability to assimilate. Truettner sees this born out in the tendency of portraitists to emphasize racial characteristics and ethnographical detail where once an effort had been made to classicize Indian subjects. Readers will likely be more familiar with the images in this section of the book, which includes paintings by Charles Bird King, Alfred Jacob Miller, Karl Bodmer, and George Catlin. To a large extent, these are the Indian pictures that have defined popular American notions of the Plains tribes.

Artists painted these Indian men and women for a variety of reasons, but they began with diplomatic intentions similar to those of earlier portraits commissioned by the British. U.S. War Department officials often brought visiting tribal delegations to Washington, D.C., portrait studios. During his tenure in charge of Indian Affairs for the War Department, Thomas McKenney acquired hundreds of such portraits, mostly painted by Charles Bird King, for the U.S. government. Yet this would be a short lived practice as McKenney was fired by Andrew Jackson (a figure who is curiously absent from Truettner’s book). Around this time, artists began traveling out West in search of “authentic” Indian subjects. Truettner sees Catlin, Bodmer, and Miller, all of whom painted Upper Missouri Indians on their home turf, as “effective in serving the government’s cause” (77). While this may be true, in that each of these artists shared a similar perception of the Indians as a vanishing race, it elides the sometimes overtly pecuniary motivations of the artists. Bodmer made his paintings for the German Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied’s exploration of the Missouri River. Catlin toured his “Indian Gallery” and certainly hoped to make money from it. Even the civil servant McKenney, though not himself an artist, tried to make a profit by borrowing the War Department’s portraits in order to make copies for the multi-volume portfolio History of the Indian Tribes of North America. This is not to say that these men couldn’t be motivated by both a financial interest and a desire to document the ways of a doomed culture, but Truettner gives much more weight to the latter. It may be that the very idea of picturing a vanishing race created a market for such images.

On the whole, the book offers keen insight into these powerful works. At roughly a hundred and fifty pages, the book is tight and lean. According to the author, the project began as a lecture, and expanded from there. A benefit of this method is that the book has a coherence and clarity that makes it ideal for classroom adoption. And I can think of no other source that brings together so many of these rich images. Although Truettner rightly notes that the book is the first to unite these two campaigns of Indian painting, I sometimes wished that he had expanded his argument further by connecting the dots between these groups. Readers might enjoy more of the “messy, drawn-out transition” between the two. As it stands, the category of Republican Indians encompasses a broad array of material, which Truettner could profitably explore further. Additionally, although the visual evidence pushes into the 1840s, Truettner almost entirely avoids the policy of Indian Removal. While this may be due to his focus on the Missouri River tribes, it might be worth considering how this policy shaped white Americans’ perceptions of the Indian.

Akela Reason is assistant professor of history at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History (2010).