On Figs: Sweetness in the common landscape

“Like Jeremiah’s figs, The good, are very good, indeed—The bad, too bad for pigs.”

Confusion embarrasses the fig. In Genesis the fig feeds Adam and Eve in their innocence and clothes them with its leaves in the awakening of their self-knowledge—the first recorded instance of “too little, too late.” Commentaries aligning the new United States with an Edenic state defined by plenty and tranquility cited 1 Kings 4:25: “And Judah and Israel dwelt safely, every man under his vine and under his fig tree, from Dan even to Beersheba, all the days of Solomon.” Nineteenth-century African-Americans regularly drew on the same passage as the rhetorical measure of freedom and equality, often in contexts of new church building from Louisiana to Liberia: “I can say for the first time since our existence as a church that we assembled in our own church and held quarterly conference; and partook of the Lord’s Supper on the Sabbath, under our own [vine and] fig tree.” Christ in the Gospel of Mark curses the fig into barrenness, a signal action given the fecundity of the fig in the time and region. Gustav Eisen, the nineteenth-century authority on figs, traces its origins to Arabia and the earliest perfection of its cultivation to the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates in present day Iraq. The fig entered the Mediterranean world with the ancient Greeks and over the millennia found its place as commodity, staple, and luxury around the world.

Native to Asia, the fig (ficus carica) came to the Americas in 1520, imported by the Spaniards to Hispaniola, five years before it made its way to England from Italy. Captain John Smith noted its existence in Virginia by 1621, the cultivar having been transplanted from Bermuda. Jane Pierce of Jamestown, the fruit’s first Anglo-American devotee, harvested 100 bushels in 1629, an amount that suggests the presence of a sizable fig orchard and preservation endeavor. By the early eighteenth century the cultivar had gone feral. John Larson’s 1709 account describes the Carolina version: “Of figs we have two sorts: One is the low Bush-Fig, which bears a large Fruit. If Winter happens to have much Frost, the tops thereof die, and in the Spring sprout again, and bear two or three good Crops. The Tree-Fig is a lesser Fig, though very sweet. The Tree grows to a large Body and Shade, and generally brings a good Burden; especially, if in light Land. This Tree thrives no where better, than on the Sand-Banks by the Sea.” Almost two centuries later, an unknown photographer captured the portrait of a Hog Island, Virginia, family with a fig tree of staggering proportions in the background (fig. 2). Visitors to the Virginia barrier islands frequently remarked on the local figs as a delicacy: “Some 300 people inhabit this island and throughout the year, and excepting those employed in the lighthouse and life-saving service, gain a livelihood from harvesting sea food. The unique features of the place are luxuriant fig trees, which bear abundantly season after season, the great number of ever present musical mockingbirds and also the primitive customs of some of the natives.” No less a dignitary (quite literally) than Grover Cleveland enjoyed island figs as the conclusion to a hunters’ banquet: “The big kitchen attached to the club was turned over to the best island cooks. There were oysters from the shores of the island, terrapin, turkey, roast beef and wild fowl of every variety, prepared in every culinary style. At dessert some preserved figs, raised on the island and the club’s special pride, were served.”

The Cyclopedia of American Horticulture described the fig as “a warm-temperate fruit” that, with protection from cold weather, could be grown in most parts of the United States. The fruit, the Cyclopedia continues, “is a hollow pear-shaped receptacle with minute seeds (botanically fruits) on the inside.” In essence, what is taken as the fruit of the fig is its flower, a blossom that grows inside out and is pollinated by a specialized wasp that enters through the tiny opening at the base of the “fruit.” Like the fig, the wasp is an exotic import and the fertilization of figs for seed in the United States is historically quite limited. Thus, the propagation of the fig from its earliest introduction into the Americas has relied on various strategies for rooting branches either clipped from the tree or bent to the ground and covered. In many areas of the South, the fig went “native” to the extent that commentators on the countryside saw it as a natural and incidental element in the domestic landscape. Jefferson Franklin Henry, formerly enslaved on a Georgia plantation, drew a distinction between orchard fruits and those that flourished on the margins of cultivated ground: “The orchards was full of good fruit sich as apples, peaches, pears, and plums, and don’t forgit them blackberries, currants, and figs what growed …round the aige of the back yard, in fence corners, and off places.”

Left in the wild, the fig sends out runners that can be cut for new plants. Significantly, figs with documented nineteenth-century and earlier histories are essentially clones of much earlier root stock—arguably making it possible to locate and continue an early American cultivar with some measure of genetic integrity. The resilience of the fig in warmer environments, its ease of propagation, and its productivity inspired one Southern author to group it in a gazetteer of Fruits That Never Fail!: “This delicious and healthy fruit—of which we have many varieties—grows almost spontaneously everywhere,” adding the caveat that “fig trees are not entirely here—they need a slight protection of pine tops or similar shelter, while young, succulent, and tender—severe winters often nip them quite sharply, but their recuperative power is astonishing.” Gardeners of all persuasions cultivated a variety of figs. Favored strains in the southeastern United States included Black Genoa, Black Ischia, Brown Turkey, Brunswick, Green Ischia, Celestial, Lemon, Havana, Large Blue, Alicante, and White Marseilles. Many of the varieties listed for sale by nineteenth-century nurseries survive in Southern gardens. The Celestial, Lemon, Brown Turkey, and other figs have been documented on the Eastern Shore of Virginia and Maryland where they sport local names—sugar figs, Crisfield whites, Hog Island, and Westerhouse green. Each variety, black and green, possessed a distinctive appearance, ripening schedule, and flavor profile. Intensely sweet and favored for preserves, sugar figs (a variety of Celestial) appear in early August. Westerhouse green figs mature in late September and offer a complex flavor at once sweet and floral. Hog Island figs, with their rich and slightly musty flavor, are also well-suited for preserves and are harvested in late August and early September (figs. 3 and 4).

A tractable tree, the fig can be trained to grow espaliered on a trellis, pruned as a tree, or simply left to its own bushy devices. Untended fig trees in the American South grow fifteen feet and more in height and as much or more in circumference. The bark ranges from pale slate gray on old growth to a greenish brown on new shoots. The leaves are deeply lobed and large with the number of lobes depending on the variety. Depending on the severity of the preceding winter, the first fruits (known as breva figs) ripen as early as late June. The largest crops, however, appear in late summer and are short lived. Because different varieties ripen in successive intervals, fig growers have been able to keep fresh figs on the table from late July until the beginning of October. For most families, though, fig season was defined by a summer moment of plenty and delight.

Although the fig ultimately achieved the status of a commodity crop in late nineteenth-century California, its greater incidence was as a seasonal treat of painfully limited market availability. Fig growing in the northeastern and Midwestern sections of the United States typically took the form of a hobby that involved sometimes extreme strategies for wintering the sub-tropical plants. In the eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries, fig cultivation in less temperate areas was the privilege of those with the means, labor, political inclination, and polite scientific knowledge to devote to the nurture of delicate plants under glass. Fig culture in the American South, however, offered a more conflicted narrative, one that blurred lines between the exotic and the everyday, the fragile and the hardy, slavery and freedom. Figs all too often anchor sentimental childhood recollections of antebellum plantation life in the South:

There were fruit trees in our garden; peaches, apricots, pomegranate and figs. We loved the figs most, of which there were several varieties. Our especial pride was the large black fig tree. There were six of us, three girls and three boys. Four of us were white and two were Negroes… Every morning in season would find us at our favorite fig tree. The boys would climb into its branches while the girls stood below with extended aprons to catch the fruit as we dropped them. Some times there came a voice from above in complaining tones—…Now Jennie! I see you eating.’ …Oh,’ would be the reply, …That one was all mashed up.’ …All right, now don’t eat till we come down.’ Then when we descended we took large green fig-leaves, placed them in a basket, laid the most perfect fruit thereon, and one of us would run to the house with it …Don’t eat till I come back.’ …We won’t.’ … When the messenger returned we went to our favorite nook in the garden and after dispatching about a dozen figs apiece we rushed to our breakfast with appetites as unappeased as if we had fasted for a week.”

Concealed within nostalgic constructions of the fig and idylls of rural Southern life is the continuing implicit link between the Garden and the Fall.

The enslaved people of Monticello likely found little of Edenic solace in Thomas Jefferson’s offhand observation that saw the ripening of the fig crop as an occasion for light labor. Writing from France in 1787, Jefferson recorded his observations on a tour through the south of France:

The fig and the mulberry are so well known in America, that nothing be said of them. Their culture, too, is by women and children, and therefore earnestly to be desired in countries where there are slaves. In these the women and children are often employed in labours disproportioned to their sex and age. By presenting to their master objects of culture, easier and beneficial, all temptations to misemploy them would be removed, and this lot of the tender part of our species much softened.”

The reality of picking and processing figs on other Southern plantations, however, did not accord with Jefferson’s sensibilities. James Roberts, born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Virginia and sold south to a southern Louisiana plantation, described in his memoir the labors of harvesting and pressing figs:

First a layer of sugar, then a layer of figs. The figs are gathered off the bush when ripe, and the box is filled up as described. Then the box is put under the hand-press, and the press is screwed down upon them. What the women and children gather in the day, the men pack at night. In the morning, at the blowing of the horn, the women and children go out again to the wood; then at night, after a heavy day’s work, the men must pack all they have gathered; and that is the rule while the figs last, which is from the first of August to the first of September.

Unlike Jefferson’s vision of gender appropriate labor, Roberts’s account placed fig culture in a context of heavy seasonal work.

Jefferson’s interest in the fig involved him in epistolary exchanges with friends and agents as he sought vital cuttings from the Mediterranean for transplantation, sent cuttings of his own to acquaintances for their gardens, solicited and gave advice (practical and political) on fig cultivation, and ordered dried figs from Europe for his Virginia table. In 1794, for example, he wrote to George Wythe: “Knowing your fondness for figs, I have daily wished you could have partaken of ours this year. I never saw so great a crop, and they are still abundant. Of three kinds which I brought from France, there is one, of which I have a single bush, superior to any fig I ever tasted any where.” Jefferson’s October figs were surely cultivated under protection and represented a rare autumn treat. Out of season, dried figs were a dessert staple for elite tables.

The art of drying figs invited periodic correspondence to nineteenth-century American agricultural papers. Earlier contributions tend to emphasize the political and economic advantages discovered in the cultivation and preservation of a homegrown exotic. A correspondent to the Southern Cultivator in 1850 succinctly addressed core themes linked to fig culture including its ever increasing presence in the gardens of poorer families, its underutilized abundance, and its political connotations: “Considering how cheaply figs may be grown, to any desirable extent, in the Southern States, and how many poor families there are who might cure and put them up for market, it does seem wrong that this country should pay from one to two millions of dollars a year to foreigners for Smyrna and other Mediterranean figs.” Thirty years later the same lament reappeared in the same paper:

Among the many varieties of fruits adapted to our Southern zone, the fig has not received all the attention it deserves, viewing it for commercial purposes. True, few gardens throughout the country are without a fig tree, but beyond supplying the table with the fruit in a fresh state, no use is made of it. No attempt seems to have been made to grow it on a large scale, for the purpose of drying the fruit and bringing it in competition with the imported article.”

The response to these declarations was modest at best. Occasional correspondents submitted various approaches to drying figs for market, but in the end the Southern fig thrived as a dooryard staple for seasonal family tables, never achieving the status of a valued market commodity.

The humid environs of the South tended to frustrate preservation efforts and require a variety of chemical and mechanical interventions. In 1852, the editors of Southern Cultivator published a correspondent’s instructions on “How to Dry Figs:”

When the Figs are fully ripe, (but not cracked open) gather them carefully on a dry morning after the dew is off. Make a weak lye of wood ashes, and having placed the Figs in a sieve or colander, pour it over them once or twice, but do not allow them to remain standing in it. Then have ready a syrup made of half a pound of sugar for each pound of Figs, boil them in this until they become transparent—then dry them on dishes in the sun, and when packing them away, sprinkle over the layers some finely pulverized sugar. Try this, and if it fails to produce a delicate and luscious article of dried Figs, you are at liberty to call me no HOUSEKEEPER.”

The editors accompanied the instructions with a challenge to their “fair” readers that encouraged “ladies” to submit their own recipes (and boxes of dried figs) for judgment. The winner received a library of periodicals (including Godey’s Lady’s Book) and books “the lady may desire.” The blending of agricultural science with housekeeping and refined femininity in the original recipe and the subsequent contest captures a transitional moment as fig culture moved from masculine traditions of polite intellectual discourse and horticultural experiment to the feminized realm of domestic arts.

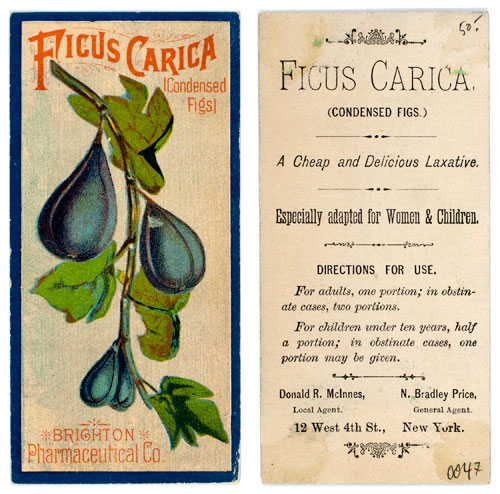

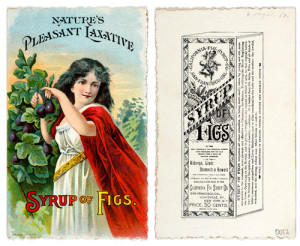

During the Civil War years, Southerners desperate for increasingly rare commodities as diverse as food preservatives and ink turned their attention to the possibilities offered by the fig. “The juice of the skin of our blue fig is abundant,” noted Confederate surgeon Francis Porcher, “and of a deep, brilliant red color; a half-page written with it a few days since had the appearance of having been done with red ink…I have seen blue cakes resembling indigo, intended for dyeing, and marked fig blue—probably extracted from the skins of the fig.” Porcher additionally recommended the fig stems for use as pipe stems and molasses. “Figs,” he added, “are excellent pabulum for vinegar,” and recommended that “vinegar should be constantly replenished with over-ripened figs.” A correspondent to the Southern Cultivator suggested fig pickles as a military ration: “Figs, properly pickled, are generally preferred even to cucumbers by those who have tried them; and large quantities should be put up for army use.” The principle advantage of fig pickles lay in their medicinal qualities: “The sharp acid of this pickle renders it a very grateful addition to the table, in spring when the bilious state of the human system demands vegetable acids, and early fruits are still unripe.” In the decades following the Civil War, the Southern Cultivator continued to note the medical efficacy of the fig, generally in syrup, beneficially acting “on the kidneys, liver and bowels, effectually cleansing the system, dispelling colds and headaches and curing habitual constipation.”

The culinary uses of figs were remarkably limited. A mid nineteenth-century writer for the Southern Cultivator neatly summarized the possibilities: “As a breakfast dish, ripe and luscious Figs are unrivaled—being more light, digestible, and wholesome than almost any other fruit. They also make a very rich and delicate preserve, and there is no reason why the whole Union may not in time be supplied from the Southern States with dried Figs, equal to those of Smyrna.” Fresh figs remain a seasonal pleasure for many households and homemade fig preserves still stock many Southern pantries. Home-dried figs, much touted throughout the nineteenth century as a new Southern commodity, remain an uncommon item at the grocery store.

In the later decades of the 1800s, the preservation of figs turned increasingly toward methods of “putting up” the fruit. Putting up recipes generally fell into one of two categories: preserving figs in a spiced sugar syrup or, less common, pickling. Although directions for pickled figs appeared in nineteenth-century publications, it was the less favored approach. A mid-century recipe for pickled figs begins “we do not know of a superior pickle or relish, nor one which will …keep with so little trouble,” and conveys something of the sense of the tartness and crisp texture of this accompaniment:

Select figs of a fair size and good quality—the common large white variety is excellent. When they are just swelling to ripen, but not soft, pick them without bruising, and let them stand in salt and water for two or three days. Then take them from this pickle, put them in a glass or earthenware jar, (not glazed) and pour over so as to entirely cover them, scalding hot vinegar, sweetened with good brown sugar, at the rate of one pound to the gallon, and highly flavored with mace gloves [cloves?], pepper and allspice. (The sugar and spices should be put into the vinegar before it is set over the fire to heat.)

The author enthuses, “Let every good Southern housewife try it.”

Figs preserved in sugar syrup remain the enduring favorite in Southern larders. Bessie Gunter’s Housekeeper’s Companion, compiled from recipes contributed by Eastern Shore of Virginia friends and their families, contains a representative example for preserves: “Scald the figs and let stand till cold. Make a syrup of one pound of sugar, a half pint of water to each pound of figs. Let the syrup come to a boil, then drop in the figs and cook slowly until done. This recipe is for little brown figs.” The quality of fig preserves in syrup varies considerably despite the fact that the basic recipe is nearly universal. Again, on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, where many families put up fig preserves at summer’s end, home cooks use their own variations on the standard nineteenth-century combination of boiling sugar syrup, spices, and figs. Violet Trower of Exmore peels her figs and cooks them slowly until the syrup is a deep caramel brown. Phyllis Walker of Bayford does not peel her figs and her syrup is considerable lighter in color and viscosity. Both are excellent. Because we do not have surviving jars of fig preserves from the nineteenth century (at least not survivals that could be consumed without life threatening consequence), our knowledge of early American flavors and palates can only be imagined through their modern iterations. Considering the transformation of sugar alone, the archaeology of taste remains a problematic endeavor.

As an ingredient, figs appeared in nineteenth-century desserts like fig cake. Bessie Gunter included instructions for two variations on fig cake along with a recipe for an elaborate Fig Ribbon Cake in her Eastern Shore collection. Ribbon cakes originated, contemporary to and not unlike crazy quilts, as a Victorian display of domestic virtuosity and extravagance. An early layer cake variation distantly related to the stack cakes of the Chesapeake Bay and Outer Banks regions, the ribbon cake was a fancy confection composed of three or more layers of contrasting colors like gold and white or red and white. An icing or fruit preserve separated each layer, and the completed cake was frosted. Gunter’s recipe uses fresh figs in an Eastern Shore variant:

White Part. 2 cupfuls sugar; 2/3 cupful butter, creamed together. Add 2/3 cupful milk; 3 cupfuls flour, alternately; 2 teaspoonfuls of baking powder, and then the whites of eight eggs (beaten lightly). Bake in two layers.

Gold Part. Beat a little more than half a cupful of butter and a cupful of sugar to a cream. Add the yolks of seven eggs and one whole egg (well beaten), half cupful of milk and one and one-half cupfuls of flour (mixed with one teaspoonful of baking powder). Season strongly with cinnamon and allspice. Put half of this gold part into a pan, lay on it halved figs closely, previously dusted with a little flour, then put on it the rest of the gold cake and bake.

Put the gold cake between the white cakes using frosting between them, and cover with frosting.

The Ribbon Fig Cake derives in part from the polite culinary culture of Victorian America but it also speaks to a continuing engagement with the vernacular landscape. When Gunter published Housekeeper’s Companion the fig was common to the kitchen yards of rich and poor, black and white. In the summer its bounty provided pleasure for all. Preserved, it evoked the taste of sun and warmth in the dark chill of winter. No longer the cultural privilege of the eighteenth-century landed elites, the fig at the close of the nineteenth century was truly an emblem of hope and plenty in the common landscape.

Further reading

The period sources quoted in this essay are available through a number of searchable online historical collections. The American Periodical Series Online provides access to a variety of nineteenth-century agricultural newspapers and journals including Farmer’s Register: A Monthly Publication, Southern Cultivator, and The American Farmer. Accessible Archives yielded The Christian Recorder and other periodicals in its African-American newspapers collection. Thomas Jefferson’s numerous references to importing and cultivating figs are contained in Barbara B. Oberg and J. Jefferson Looney, eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition (Charlottesville, Va., 2008). Quoted materials on the Eastern Shore of Virginia were derived from The Countryside Transformed: The Railroad and the Eastern Shore of Virginia, 1870-1935 (http://eshore.vcdh.virginia.edu/). Materials drawn from memoirs and diaries were located in digital collections of “Documenting the American South,” University of North Carolina Library. These include Sam Aleckson, Before The War, and After the Union: An Autobiography (Windsor, Vermont, 1929); John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina; Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of That Country: Together with the Present State Thereof… (London, 1709); and James Roberts, The Narrative of James Roberts, a Soldier Under Gen. Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans, in the War of 1812: A Battle which Cost Me a Limb, Some Blood, and Almost My Life (Chicago, 1858). References to figs are found occasionally in American Memory, Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writer’s Project, 1936-1938, Library of Congress (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/snhtml/).

Monographic sources include: Stephen L. Buchmann and Gary Paul Nabhan, The Forgotten Pollinators (Washington, D.C., 1996); Gustav Eisen, The Fig: Its History, Culture, and Curing with a Descriptive Catalogue of the Known Varieties of Figs (Washington, 1901); Bessie E. Gunter, Housekeeper’s Companion (New York, 1889); Peter J. Hatch, “Figs: ‘Vulgar’ Fruit, or ‘Wholesome Delicacy’,” The Fruit and Fruit Trees of Monticello (Charlottesville, 1998); John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina; Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of That Country: Together with the Present State Thereof… (London, 1709); Francis Peyre Porcher, Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, Medical, Economical, and Agricultural. Being also a Medical Botany of the Confederate States; with Practical Information on the Useful Properties of the Trees, Plants, and Shrubs (Charleston, 1863); Charles H. Shinn, “Fig,” in L. H. Bailey, ed., Cyclopedia of American Horticulture (London, 1900).

This article originally appeared in issue 11.3 (April, 2011).

Bernard L. Herman is the George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Folklore at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. His recent essays and books cover a range of topics including eighteenth-century urban housing and city life, Eastern Shore of Virginia foodways, the art of Thornton Dial, and uncollectable craft. He currently holds a Guggenheim Fellowship for a book project, Troublesome Things: In the Borderlands of Contemporary Art.