On the Road Again

I learned many things about doing historical research in graduate school: how to formulate a workable project, how to find and analyze primary sources, how to build on the preceding secondary literature. There were no sessions devoted to “aura,” and there still aren’t, within my ken. Yet “aura” has, for me, turned out to be an essential element of my research and writing strategy, as I am sure it is for many historians. When in the grip of a compelling project, as I eagerly search out documentary evidence relating to my characters and their events, I feel an urge to visit the places they lived and traverse the roads they took, as much as possible. In part, I travel to soak up atmosphere, to get a feel for a place that will enable me to write about it with more authenticity and credibility. In part, I travel because there are always useful local records in libraries and courthouses that can provide some missing clue. But there is something else, too, that I find hard to articulate, that I gain from these pilgrimages.

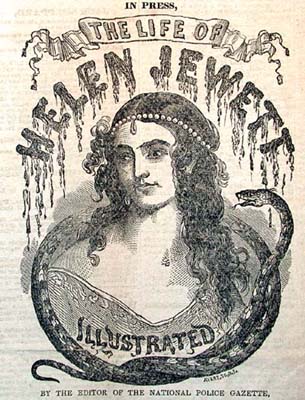

Let me rush to say that it takes a lot of advance library work to make these site visits valuable. I’ve made visits underprepared, and the payoff is usually small. A decade ago, when I first came across the crime pamphlets relating to Helen Jewett, a New York City prostitute murdered in her brothel in 1836, I was immediately grabbed by the mystery surrounding not only her death but her life. The big-city newspapers reported on three different versions of her Maine origins, and the pamphlet literature added another three or four variants. Based on armchair sleuthing in Maine county history books and census schedules, I pinned her down to Augusta. I was living in Massachusetts that year, and I proposed to my family a weekend trip up to Maine. Advice: try, if possible, not to take children along on aura-seeking trips. It’s the rare child who has the patience to watch you wander down seemingly nondescript blocks of houses or main streets that look remarkably like the houses and main streets in other towns. On that first trip, we saw the coast of Maine, beautiful lakes, Acadia National Park, and Augusta–the latter for all of a half hour, I’d say. We parked the car near the 1830 Kennebec County Courthouse while I strolled around a few neighboring blocks, admiring the many 1830s residences. But I couldn’t get a mental fix on anything; I hadn’t done my homework. We even missed the wonderful historical site specifically set up to transport tourists back to the earliest Augusta history–Fort Western, built during the French and Indian War.

I made two subsequent trips to Augusta in the next several years and spent days, not hours. Part of my time was devoted to standard archival research: studying maps and local newspapers at the Fort Western Museum, town vital records and papers at the Maine State Archives, and the huge dusty tomes of land conveyance records in the basement of the courthouse. But equally important was my imagination’s soak time, achieved by walking the streets, peering around buildings, and staring the placid Kennebec River back into a rushing torrent by mentally removing the 1838 dam. By now I knew that Helen Jewett had been a servant in the family of Judge Nathan Weston, the first judge to preside over the courtroom in the courthouse, where I found his picture hanging on the wall. Now I also had an 1838 map of the town, an exceptionally detailed, large map that showed the footprint of every house in town. (It had been made on a blueprint copier machine at the Fort Western Museum for historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich when she was working on A Midwife’s Tale, and she spontaneously handed it to me in one of those generous gestures for which she is famous.) Armed with that map, and an early-twentieth-century book I found in the Augusta public library that listed the successive owners of many of the older houses in town, I could go stand in front of the very houses where my Augusta cast of characters lived.

Perhaps because these were all still private residences, I was too chicken to knock on any doors. But in Newburyport, Massachusetts, I located the large Federal-style house where George P. Marston grew up; it had become a funeral parlor. Young George was a clerk in New York City in 1836, a lover of Helen Jewett and a man lucky to escape the finger of suspicion in the murder case. His father had been a judge and shipowner in this Massachusetts port town, and proud descendents in the early twentieth century had published a book of family reminiscences (stripped clean of any allusions to prostitution and murder, naturally) that included a photograph circa 1900 of the Marston family home. As I stood gazing at it, doing my aura thing, trying to imagine the George I knew from his letters and trial testimony actually bounding out of the house before me, an employee of the funeral parlor emerged to ask if I needed help. When I explained my mission, he invited me in and gave me a tour of the place–all but the kitchen, where the corpses were kept.

And so it went. I traipsed the brothel blocks of 1830s Portland, Maine, now lined with mostly late-nineteenth-century residences, and the graveyards of Temple, Maine, a village of about eight hundred persons where Helen Jewett had been born in 1813. In New York City, I spent many hours reconstructing the succession of lots and property owners on the block where Jewett was murdered in her brothel. I had first assumed that the house at 41 Thomas Street was at the end of the block, since there was no house with a larger odd number according to the 1836 city directory. But the conveyance records clearly mapped it in the center of the short block. (Deep lots facing around the corner on Hudson Street accounted for the apparent discrepancy.) I examined fire insurance maps to learn about the brothel’s basic structure–brick, with two skylights in the roof–and also to learn about when the current commercial building on the lot replaced it. And I visited the site, perhaps seven or eight times, over the decade that I worked on the project. The street looks completely different today, of course. But its spatial configuration is the same–the narrow width of the street, the thirty-three-foot frontage of the brothel and now of the commercial building that took its place around 1869). As I stood alone in the middle of Thomas, I conjured up the crowds that milled there in the weeks after the murder, hoping for a sight of the much-rumored Helen Jewett’s ghost. I didn’t see her ghost, but I could–almost–sense the crowd.

I don’t believe in ghosts, and I never actually “see” my characters on these trips. A waiter in a dark western bar in Nacogdoches, Texas, the town where Jewett’s acquitted murderer, Richard Robinson, fled to in 1836, told me there was a tale that the bar was haunted. I smiled gratefully; I was in fact eating there precisely because I knew the bar was on the site of Robinson’s saloon of the late 1830s. I’d read Robinson’s business account book, knew he had gaming tables and sold whiskey by the glass–details recovered by patient sifting through maps, deeds, and old photographs at the East Texas Research Center at the Stephen F. Austin State University.

The Jewett book is behind me now, and I am on the road again, this time seeking to channel the spirits of Thomas Low Nichols and his wife Mary Gove Nichols, two health and sex reformers of the 1840s-50s. They became serious Spiritualists, which at least raises the possibility that when I go around to their old haunts, they might indeed try to speak back. I have had the feeling from the beginning that I was fated to write about them. Thomas Nichols’s name kept popping up in my research on another project, a study of the “flash” press of New York City in the 1840s, a set of weekly papers that functioned like trade journals for the brothel world. (The AAS has a superb collection of these scurrilous sheets.) Editors of these papers made “thomas l. nichols” a running joke, portraying him as an arrogant jerk and an absurdly inappropriate ladies’ man among the frail sisterhood. Finally his name clicked with me, as I realized that this was the Thomas Nichols I already knew as the respectable doctor-husband of the water-cure advocate and physiology lecturer, Mary Gove. From that moment, it was a foregone conclusion that I would sleuth out these two. They shared a notorious career as Free Lovers in the 1850s and kicked up quite a storm, before they ditched it all for Catholicism and exile in England.

This fall I spent a weekend in Nichols’s hometown, a lovely New Hampshire village named Orford along the Connecticut River. (I’ve moved up in the world too: I now spring for the historic bed-and-breakfast inn over the thirty-six-dollar-per-night motel that was my operations base in Augusta.) Thomas Nichols described this village in fond detail in two of his books, but he omitted–deliberately obscured, really–his parentage and siblings. My goal was to root him in a family in that town, and to figure out how such a talented, learned, but also cocky fellow could be the product of this rural village. Orford’s tiny main street is entirely preserved as a historic district, so no doughnut shop or gas station mars my effort to envision the past. Around me I see one general store (in an 1802 building in continuous use as a store), one social library, several churches, and about a dozen very fine old homes circa 1800-30. My time-travel effort actually requires me to jazz the place up; in 1830 the township population was more than double what it is now, and these quiet blocks supported eleven taverns and a three-story hotel.

Two hours in the county court’s land conveyance records yield pay dirt: I now have a fix on land owned by everyone named Nichols in Orford and surrounding townships. A plus: the deed entries show the webs of financial connections between property in this town and a wealthy Nichols family in Salem, Massachusetts. A lot map shows me the slice of land along the river owned by one Nichols in the 1810s, and happily for me, there is a house on that lot now, with the date 1818 over the door. My photograph of it will be pinned on the wall over my computer, to stimulate my imagination as I write. There is one existing building I know for certain my quarry spent important time in: the academy in Haverhill, ten miles up the river, and from the exterior, it appears to be little changed from 1830. And my trip to Orford yielded the clue I needed to locate Thomas Nichols in his family, found in church records kept in the social library. My roué and reformer was the son of a Baptist clergyman.

Successive weekends this year will be devoted to trips to Goffstown and Weare, New Hampshire, and to Lynn, Massachusetts, places where Mary Gove lived. Already I am collecting the advance-trip data I will need, from town histories, city directories, ads in old newspapers, maps, and items gleaned from Ancestry.com and tourist-based Websites. (This last source of information has been invaluable, especially for pictures of historically important structures.) When I go, I’ll know where her house was, where the lyceum was, where the Universalist church was where she lectured on Associationism.

What does all this aura seeking gain me? I think there is no doubt that it helps me fill in missing spaces between the written words of documents on which historians mainly rely. Without a landscape, words on paper can just be–words on paper. In our movie-laden world, readers are made happy by getting a visual feel for the space historical figures inhabited. After the Jewett book came out, I got inquiries from newspaper reporters as to whether Jewett’s brothel still stood in Manhattan. It does not, of course, but there are 1830s buildings here and there in the Fifth Ward that I had sought out, and I was able to take a New York Daily News columnist and photographer on a tour of those sites. I was invited to lecture in Augusta, Maine, by the Kennebec Historical Society, courtesy of avid localist Anthony Douin, who also arranged for Judge Weston’s house to be open for a public tour–a special delight for me, of course. Where once I had been a lurker around these old buildings, now I was a welcomed guest, introduced by the mayor of the city and credited with adding Helen Jewett’s name to the Augusta roster of famous past figures.

What I am drawn to, clearly, is the hope that I can get to know my characters more fully and get them as close to three dimensions as possible. Writing history requires acts of historical imagination that are, I am convinced, extremely different from what novelists do. I could not write a work of short fiction if my life depended on it, but if I have enough written evidence about my historical characters, and if I can walk where they lived and walked, then I feel pretty sure of my ability to render them in some more fully-rounded way. At some point, they become nearly real people to me, in a way that makes me feel I would know them if I suddenly somehow encountered them.

Not as ghosts, however. Instead, I confess that I occasionally troll on eBay in spare moments, looking over the several scores of unidentified portrait miniatures for sale there. Jewett and her killer Robinson exchanged pictures, but they disappeared from the district attorney’s indictment records in New York where they were last known to be in 1836. If they do yet exist and ever make it to eBay, I’ll find them. I feel sure I would recognize them both.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.2 (January, 2002).

Patricia Cline Cohen, a professor of history at the University of California at Santa Barbara, is the author of The Murder of Helen Jewett: The Life and Death of a Prostitute in 19th-century New York (New York, 1998). She is the Mellon Distinguished Scholar at the American Antiquarian Society for 2001-2002.