Opting Out

If, as more and more scholars now affirm, the American Revolution was a civil war, how does that framing open the door to comparisons to uprisings elsewhere? I began thinking about revolution-as-civil-war while writing my first book, Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Carolina, about the attempts of North Carolina farmers on the eve of the American Revolution to create economic and political justice. The Regulators were defeated by the very men who shortly afterward led North Carolina into revolution. Many backcountry farmers proved disaffected or “neutral” during the American Revolution, skeptical that their erstwhile opponents could bring them the economic democracy and independence for which they had already fought without success. Such disaffection was common. As Michael McDonnell and others have suggested, perhaps as many as three-fifths of all Americans chose to remain neutral in the War of Independence. As I conducted research for my next project about a large and long-lasting slave rebellion in an eighteenth-century Dutch colony west of Suriname, I was struck by how many people there, too, were neither committed rebels nor loyalists. Rather they ducked, opted out, or took off on their own. These “disaffected” have been little studied, in the American Revolution or in slave rebellions.

The way historians have framed both the American Revolution and slave rebellions accounts for their reluctance to engage the topic of the disaffected. The emphasis on liberal notions of freedom as the goal of revolutions and insurgencies renders opponents and “fence-sitters” morally suspect. Moreover, it leads historians to privilege the anti-colonial contest over political struggles and conflicts among people in their own communities. Consequently, we know a lot more about the aspirations and political ideas of revolutionary leaders (usually male) than we do about the fence-sitting rank and file. As historians, in other words, we privilege people’s identities as colonized or enslaved beings, rather than as members of specific communities with aspirations and dreams that are not all related to being national or imperial subjects. We have studied colonists and slaves in rebellions more as embodied legal categories than as multi-dimensional human beings. Let me use my current work to expand upon this.

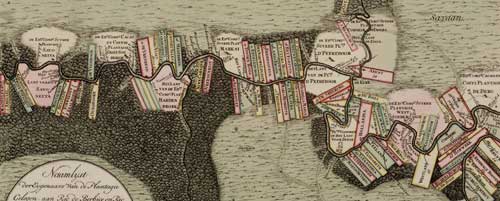

I am writing a book about a little-studied but well-documented slave rebellion in Berbice, a small Dutch colony in today’s Guyana in South America. The rebellion started in February 1763 and lasted eighteen months, longer than any slave rebellion prior to it. My source base includes the examinations of some 900 enslaved people, about a third of the adult enslaved population, taken as the rebellion wound down. These judicial records, along with other sources, offer a picture of the events from the perspective of the enslaved. The testimonies suggest the need to re-evaluate our emphasis on freedom in revolutionary narratives.

Historians have tended to assume that enslaved people inevitably, and eagerly, resisted slavery in a quest for liberty. Yet in fact, in the Berbice rebellion, many enslaved people were reluctant to join. Many were distrustful of the rebellion’s leadership, ethnic “Amina,” Akan and Ga speakers from the Gold Coast and its hinterland who favored upward mobility through the ownership of slaves. Others were unprepared to risk everything in violent rebellion. After all, while rebellions such as those of the Dutch against Spain in the Eighty Years War (1568-1648) or the American colonists against Britain during the American Revolution (1763-1783) were slow to unfold, giving people months if not years to decide their loyalties, slave rebellions required of those who were not involved in the planning split-second decisions under chaotic and dangerous circumstances. Yet others appeared not to agree with the plans of the rebels to establish a new coercive labor regime in a state with themselves on top. Consequently, the rebels had to use force to get people to participate, and they even re-enslaved some of their compatriots to ensure that work on the sugar plantations continued.

And so, not surprisingly, people’s responses to the insurgency varied. Some chose to join the Dutch. Many joined the rebels. Yet many others, perhaps the majority, while they might have joined in the plunder of their masters’ houses, remained aloof, choosing no allegiances. By their own accounts, they hid in the woods and savanna behind their plantations as soon as they heard the rebels approach and they moved back to their plantations when the rebels had passed by. Some no doubt claimed non-involvement to avoid prosecution. Others likely spoke the truth. The very fact that so many thought such claims believable is suggestive. It makes sense that people would have been wary, and preferred watching events from afar. They would have wished to keep their children and elderly safe, to protect their huts from fire, their produce from confiscation, and their chickens from the rebels’ barbecues. They may have disliked or mistrusted those who supported the insurgency on their plantations, especially drivers (always men), who may well have disciplined them in the past. And they no doubt feared Dutch or rebel retaliation if they bet on the losing side.

But we should not assume that hiding from the rebels only signaled a fearful refusal to participate in the rebellion. Likely, for many it was as much a statement about their own preferences for life without masters, a declaration of independence if you will. By hiding, former slaves in fact became maroons in their own backyards, living independently of the Dutch and the rebels, near their gardens and plantation food supplies, if those had not been destroyed or taken, in their own communities. This alternative may have been preferable, especially for women, children, and the less-able bodied, to joining a military and violent rebellion.

So the freedom paradigm does not hold up very well. The rebellion did not bring “freedom” to everyone, “freedom” did not mean the same to all, and many people turned down this version of “freedom.”

This account of the Berbice rebellion suggests the need to investigate the aspirations of the mass of enslaved people rather than assume that every enslaved person cared only about the kind of liberty rebel leaders dished up. Rather than focus exclusively on the fight against Dutch slavery, we need to ask questions related to social relations in the insurgency: how did enslaved people relate to each other, how was power distributed among them, what internal conflicts plagued their communities, and to what did they aspire? Historians are asking such questions for the American Revolution (though the answers have so far only minimally changed the rhetoric of liberty), but historians ask such questions less frequently for slave rebellions.

One important facet of internal politics and horizontal relations, often left unexamined, is gender. How did gender shape the experience of rebellion and civil war, once they were underway, and how did it complicate collective resistance?

In Berbice, it turned out, men could profit greatly from rebellion, while women more often lost out. For men, whether they joined eagerly or were pressed into rebellion, military service in the rebel army opened up significant avenues for advancement, enrichment, and prestige. Women were not allowed to be soldiers, and they were by and large excluded from rebel military and political leadership. In fact, some women were passed around as spoils of war, serving as tokens of prestige among prominent male rebels. They sustained the soldiers with domestic services, including sex. Moreover, women became the majority of forced plantation workers.

Perhaps in part because armed rebellion presented them with fewer opportunities to change their lives, it appears that women constituted the majority of those “opting out,” choosing marronage-at-home. But over time, especially once the Dutch mounted a massive counteroffensive six months into the rebellion, most of them became refugees. Fearful for their lives, they wandered the jungle and savannah in search of food and shelter, pursued by all parties. Such women negotiated warfare, hunger, and disease encumbered by children and the elderly, an experience that was anything but liberating. They were “free”—there was no master—but they found themselves enslaved in a new way, to survival. Many eventually “voluntarily” surrendered to the Dutch.

And so, while men and women shared much in rebellion, their experiences also powerfully diverged. For men, the prolonged military conflict offered opportunities for increased status and new identities as soldiers and leaders, from which women were largely excluded. War created novel hierarchies that gave advantages to men over women. As an emancipatory process, in other words, slave rebellion did not work the same for all. Focusing on women brings into sharp relief what rebellion meant to the great majority of enslaved people in Berbice: not freedom served up by sword and bullet, but a scramble for life that imposed devastating choices.

There are important parallels here with what historians are saying about what I might call the “silenced majority.” By emphasizing human freedom as the righteous goal of both the American Revolution and of slave rebellions, we have turned those who tried to stay out of the fray into morally suspect people unworthy of study. And that emphasis has led us to prioritize vertical relationships—those of colonizer vs. colonized; slave master vs. enslaved—over horizontal ones—those among colonists and within the slave quarters. We have given short shrift to the internal politics of colonial and enslaved communities, and we have been averse to seeing inequalities and conflicts within either population in our eagerness to affirm unity in fighting for universalized understandings of freedom that were highly manufactured. As a result, we have cut ourselves off from grasping the aspirations and politics of the majority of people caught up in these major upheavals, in the process shearing slave rebellion of its moral complexity.

So I would like to make several suggestions. First and foremost, we need to write new narratives of revolution and rebellion that do not rely on a rhetoric of “freedom.” Second, we need to focus on the internal politics and divisions of communities and on both leaders and the rank and file. Third, we need to take seriously the activism of the disaffected and the “neutrals,” realizing that their politics are, of course, never “neutral.” And lastly, we should pay greater attention to how civil war and violence shaped—and hindered—processes of emancipation.

Further Reading:

For a call to study the internal politics of resistance, see Sherry B. Ortner, “Resistance and the Problem of Ethnographic Refusal,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 37:1 (1995): 173-93, and Vincent Brown, “Social Death and Political Life in the Study of Slavery,” American Historical Review 114:5 (2009): 231-49. For a cogent summary of the “disaffected” in the American Revolution, see Michael McDonnell, “Resistance to the Revolution,” in Jack P. Greene and J.R. Pole, eds., Companion to the American Revolution (London and New York, 2000): 342-351.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.3 (Spring, 2014).

Marjoleine Kars chairs the Department of History at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC). She is writing a book about the Berbice slave rebellion of 1763.