Slaves You Have Never Seen

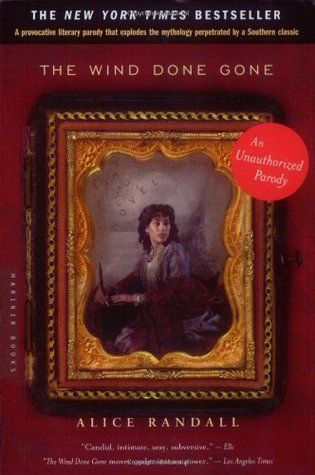

Uncle Tom. Mammy. Topsy. Prissy. Kunta Kinte. Fiddler. Chicken George. These characters shine as stars in the American cultural firmament of chattel slavery (with Little Eva, Simon Legree, Scarlett O’Hara, and Rhett Butler as their white cosmic counterparts). As literary characters–from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (1936), and Alex Haley’s Roots (1976)–brought to life in film adaptations, they reinforce visually the relationship between slavery, region, culture, and history so central to their novelistic precursors. But what are the connections between written representation and filmic adaptation? For example, how does Mitchell’s character of Mammy compare to Hattie McDaniel’s Oscar-winning portrayal in the 1939 film? It is often difficult to discern where the power of narrative ends and the spectacle on the screen begins.

These types of questions are at the heart of Natalie Zemon Davis’s new book, Slaves on Screen: Film and Historical Vision, derived from her delivery of the 1999-2000 Barbara Frum Historical Lectures at the University of Toronto. Davis begins with a basic question: How can film best be used as a medium for presenting history? “Readers may well wonder whether we can arrive at a historical account faithful to the evidence if we leave the boundaries of professional prose for the sight, sound, and dramatic action of film” (3). Functioning, on the one hand, as a kind of “microhistory” and, on the other, as a “creature of invention,” the feature film wields an “historical power” that “stems from its multiple techniques and resources for narration” (5-7). It is precisely this play between fictiveness and fact so characteristic of feature film (in comparison to documentary film, docudrama, or cinema verite) which makes the genre intriguing to Davis. Although feature films have been described as having little “significant connection to the experienced world or the historical past,” this same genre also has the ability to “make cogent observations on historical events, relations and processes” (5). Davis, esteemed historian of early modern France and professor emeritus at Princeton, boasts impressive credentials to address the relation of history to film. In the early 1980s, she served as historical consultant on the French production of Le Retour de Martin Guerre(dir. D. Vigne) about a case of imposture in sixteenth-century France, wrote The Return of Martin Guerre (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), a traditional historical account of that case, and taught graduate seminars in the 1980s and 1990s on History and Film.

Davis addresses the relationship of film to history in four ways. First, she strategically chooses five films about slavery or, more particularly, about resistance to slavery that serve as case studies. They include Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960), Gillo Pontecorvo’s Burn! (1969), Tomas Guiterrez Alea’sThe Last Supper (1976), Steven Spielberg’s Amistad(1997), and Jonathan Demme’s Beloved (1998). These films represent a forty-year span of productions in the U.S., Cuba, and Italy. They are set in a range of locales in the Atlantic World, including the West Coast of Africa, the U.S., Cuba, and the imaginary island of Quiemada, and document a range of action, from slave rebellion on land, slave revolt aboard ship, and slave resistance on the plantation. Second, she maps the classical duality between history and poetry onto the dichotomy between historical prose and historical film. “The ancient contrast between poetry and history, and the crossover between them, anticipate the contrast and crossovers between historical film and historical prose. Poetry has not only been given the freedom to fictionalize but it brings a distinctive set oftechniques to its telling: verse forms, rhythms, elevated diction, startling leaps in language or metaphor. The conventions and tools of poetry can limit its use to convey some kinds of historical information, but they can also enhance its power for expressing certain features of the past” (4). Third, she offers a dual chronology of twentieth-century historiography on classical and New World slavery and of filmic representations of slavery in the same period. She sees “shifts in cinematic treatment of slave resistance over the decades [that] were parallel to or followed on similar changes in the work of historians” (123). Fourth, Davis reads these films against their broader social and cultural contexts.Spartacus is a film about internal Roman politics and the political and social revolt against Roman elites;Burn! and The Last Supper concern political economy and local cultural customs; Amistad focuses on political struggles and the claims of property; andBeloved explores the cultural and psycho-social trauma associated with slavery. She also harnesses the personal anecdotes of these films’ filmmakers, actors, and writers to flesh out their creative contexts.

Davis continues with a follow-up query to her initial question: “what do films about slavery tell us about the past?” (19). She reveals her dual faith in the medium of film and in the possibility of making films that are “both good cinema and good history” (xi). The films she analyzes give “her new eyes with which to look once again at the plantations, uprisings, and manumissions of Suriname” at the center of her current research (xi). “As long as we bear in mind the differences between film and professional prose, we can take film seriously as a source of valuable and even innovative historical vision. We can then ask questions of historical films that are parallel to those we ask of historical books. Rather than being poachers on the historian’s preserve, filmmakers can be artists for whom history matters” (15).

While Davis’s erstwhile contention about the potential symbiosis between history and film is one that most of us can share conceptually, the history of the documentation of slavery as a subject for film is a sad and sorry one (I have included a comprehensive, though not exhaustive, list of films at the end of this review). Any visual representation of slavery in a U.S. context depends for its signification upon a complex visual and discursive network of meanings about race, class, labor, gender, and region. In this sense, what films about slavery tell us about the past is that it is incredibly difficult to talk about or conjure up images of the institution fashioned by slavery. Put differently, the symbiosis between history and film means that film can get it just as wrong as history, with more long-lasting and visually explicit results (take the visual iconography of a shiny-faced, wisecracking Mammy in Gone With the Wind as one notable example). From the nascent silent classic ofUncle Tom’s Cabin in 1903 to the technically brilliant, yet reactionary Birth of a Nation in 1915, from the audaciously repellent Operation 13 (1930s bombshell Marion Davies as a Union spy during the Civil War ‘blacks up’ as a slave maid behind enemy lines), to the shadow-filled tableaux of Jezebel of 1938 in which slaves silently tend to Bette Davis cast as an overwrought southern belle, Hollywood’s attempts at depicting American slavery seem awkward at best and plain racist at worst. Instead, the only instance in which slavery can be discussed openly is in its classical form–Hollywood’s “ancient world” is almost entirely populated by Anglo actors. In this sense, white actors Charlton Heston in Ben-Hur and The Ten Commandments and Kirk Douglass in Spartacus decrying their bondage both sound and look fundamentally different from black actor Denzel Washington narrating the physical and psychic terrors of his chattel existence after joining the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment of the Union Army in the Civil War epic of Glory. By Hollywood standards, the “slavery” experienced by Jews and non-Romans in the classical era has nothing in common with the “slavery” borne by persons of African descent in the New World. Instead audiences encounter slavery in whiteface–white Hollywood stars sport burlap and chains and spout platitudes about freedom and justice.

Indeed, in this sense, Slaves on Screen is perhaps a misleading title. Readers may find the slaves on which Davis focuses–Spartacus, Jose Dolorés, Sebastián, Cinque, and Sethe–to be relative strangers in contrast to the familiar figures of Uncle Tom, Mammy, or Kunta. The slaves Davis has chosen have not been seen much at all. Only one of the five films, Spartacus, was a commercial success. BothBurn! and The Last Supper require the prodigious inventories of an art house video store just to screen them (and even here near Hollywood, I had difficulty locating them). Amistad and Beloved were box office failures–even Spielberg’s blockbuster auteur status and Oprah Winfrey’s formidable marketing power could not overcome the movie-going public’s ingrained reticence about and avoidance of the devilish details of chattel slavery.

The relative obscurity of these slave characters is reinforced by a telling omission in the broad social and cultural context drawn by Slaves on Screen. This volume would have benefited from even a cursory consideration of the efforts of black writers and filmmakers in the post-Civil Rights era to confront the history of slavery. There is little mention of Alex Haley’s Roots (Garden City, N.Y., 1976). The immensely popular television series (1977), based upon the best-selling text, has revolutionized the visual depiction of American slavery during the last twenty-five years and brought slave characters like Kunta Kinte, Kizzy, Fiddler, and Chicken George and the broad outlines of the practice of slavery into America’s living rooms. Other television movies likeThe Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1974), based upon Ernest Gaines’s novel, and later independent productions, like Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) and Haile Gerima’s Sanfoka(1993), receive no mention.

Davis’s final case study pairing Amistad and Belovedreveals how the symbiosis between film and history can go astray when its subject is chattel slavery. In other words, what happens when the power of film to impart historical knowledge is muted by broader cultural silence about and evasion of the film’s subject? She herself offers an oblique reference to the anomalous place of these two films in her broader argument. “Unlike Spartacus, which was made amid the troubles of the Cold War and the Red Scare, or Burn! and The Last Supper, which were produced in the wake of national revolutions,Amistad and Beloved were composed under the shadow of Holocaust” (69-70). I might paraphrase this last idea. These two films were made under the shadow of films of the Nazi Holocaust, particularlySchindler’s List (dir. S. Spielberg, 1993). Although the original materials for both films predate Spielberg’s epic chronicle, the filmic representations of those materials seem indelibly marked by the 1993 film. Indeed, Davis quotes Oprah Winfrey’s declaration about the film adaptation of Beloved to her scriptwriter and fellow producer: “This is mySchindler’s List.” I would argue that Winfrey’s substitution of Schindler’s List for Belovedilluminates the absence of language with which to speak about the experience of slavery in the New World on its own terms. Similarly, Spielberg’s own contention that he made Schindler’s List for his white children and Amistad for his black (adopted) children reveals the degree to which contemporary movie making about slavery may have little to do with the past it sets out to recreate. As Davis cautions her readers, “historical films should let the past be the past. The play of imagination in picturing resistance to slavery can follow the rules of evidence when possible, and the spirit of evidence when details are lacking. Wishing away the harsh and strange spots in the past, softening or remodeling them like the familiar present, will only make it harder for us to conceive good wishes for the future” (136).

Ultimately, Slaves on Screen raises more questions than it answers: What are the ramifications of the choice of slavery as the subject of this meditation on history and film? How does the absence of slavery from popular cultural discourse in the U.S. impact an audience? Spielberg’s and Demme’s attempts to fashion film narratives that would appeal to popular audiences fell flat. Moreover, when questions of history and media are present, how important is the factor of audience, whether popular or critical? What are the shifting fates of these various films in the broader entertainment marketplace? Finally, Davis’s last question about what movies about slavery tell us about the past remains largely unanswered. But I will venture a reply: these films tell us how desperately we need an oral and a visual vocabulary with which to speak about a past that is still our present and will be our future.

Additional Viewing:

The following is a list of films that deal directly with issues and history of chattel slavery and slave trade. Unless otherwise noted, films were released as features.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (silent film, dir. E. Porter), 1903.

Birth of A Nation (silent film, dir. D.W. Griffith), 1915.

Ben-Hur (silent film, dir. F. Niblo), 1926.

Operator 13 (dir. R. Boleslavsky), 1934.

Souls at Sea (dir. H. Hathaway), 1937.

Jezebel (dir. W. Wyler), 1938.

Gone With the Wind (dir. V. Fleming), 1939.

The Ten Commandments (dir. C. DeMille), 1956.

Raintree County (dir. E. Dmytryk), 1957.

Band of Angels (dir. R. Walsh), 1957.

Tamango (France, dir. J. Berry), 1957.

Ben-Hur (dir. W. Wyler), 1959.

Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (television movie), 1974.

Mandingo (dir. R. Fleischer), 1975.

Drum (dir. S. Carver), 1976.

Roots (television miniseries), 1977.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (television movie), 1987.

Glory (dir. E. Zwick), 1989.

Daughters of the Dust (independent film, dir. J. Dash), 1993.

Sankofa (independent film, dir. H. Gerima), 1993.

Middle Passage (Martinique, independent film, dir. G. Deslauriers), 2000.

This article originally appeared in issue 1.4 (July, 2001).

Judith Jackson Fossett is an assistant professor of English and American studies & ethnicity at the University of Southern California. She is co-editor of Race Consciousness: African-American Studies for the New Century (New York, 1997), and is currently completing a manuscript entitled Illuminated Darkness: Slavery and its Shadows in 19th-century America.