You Say You Want A Second Revolution?: The War of 1812 and Theater in the United States

Even in its bicentennial year, the War of 1812 remains an enigma to most Americans. When thought of at all, “Mr. Madison’s War” is probably best remembered as the war that gave the country its (unsurprisingly) violent national anthem before the memory trails off into vaguely recalled descriptions from old history classes of a “second Revolution” or a war that confirmed the United States’ independence. (Woe to the parent or to the teacher who is asked about the importance of this war without prior warning!) Even in the teaching profession, I suspect most of us would prefer to focus on the surprising naval victories and the successful resistance of Fort McHenry, quietly ignore the burning of Washington, and get on to the westward expansion, thank you very much. In Canada, meanwhile, the War of 1812 is a major part of the social studies curriculum as early as elementary school and has been the subject of considerable public observance this year, including revivals of playwright Michael Hollingsworth’s 1987 The War of 1812, part of his play cycle chronicling Canada’s national history. In the United States, however, even the anniversary-oriented uptick in scholarship on the war has left our national perceptions in a muddle. Recent histories of the war have presented fresh nationalist (1812 as second Revolution) and Atlanticist (war with sweeping effects on relations among the United States, Britain, and Canada) narratives, and also accounts tied to the development of the United States Navy and even the war’s relationship to the evolving marriage of James and Dolly Madison. Nonetheless, as the title of Donald Hickey’s recently reissued classic history suggests, the War of 1812 remains, insofar as it is understood, A Forgotten Conflict. As a nation, we just don’t know what exactly to make of our second war with the British.

For the most part, the 1812 conflict has been erased from the physical landscape of the country. A visitor to the District of Columbia would have precious little reason to think the British had once burned the upstart capital. A short drive away in Maryland, a few more concrete reminders exist. Listening to “The Star Spangled Banner” at a Baltimore Orioles game, Fort McHenry’s presence a few miles to the east becomes somehow more historically immediate. In 2010 the state adopted a blatantly patriotic new red, white, and blue license plate depicting the bombardment of Fort McHenry to commemorate the war. A few miles to the south in the state capital, Annapolis, visitors to the United States Naval Academy who enter Memorial Hall, the school’s central commemorative space, will see a banner emblazoned with the Navy rallying cry, “Don’t Give Up The Ship.” The slogan predates the Academy’s 1845 founding by several decades. These were the last words of Captain James Lawrence aboard the USS Chesapeake as the HMS Shannon raked his ship with cannon fire in 1813; the motto was later stitched into the battle flag flown aboard the USS Lawrence under then-Captain Oliver Hazard Perry at the Battle of Lake Erie. The War of 1812 does not lack for moments of high drama.

Despite its dramatic potential, however, the War of 1812 has suffered from a relative paucity of narrative attention. Trapped in between massive multi-part documentaries about the Revolution and the Civil War, it must be content with a two-hour special. With the pop-history craze once known as “Founder-mania” on one side and our seemingly insatiable appetite for stories of the “War Between the States” on the other, the most prominent reference to the War of 1812 that I can recall in pop culture is a stray moment in Martin Scorcese’s 2002 epic, Gangs of New York. Daniel Day Lewis’s character, the fictional nativist gang leader Bill Cutting, is approached by Tammany Hall leader Boss Tweed on the docks of New York City, where Cutting is throwing rocks at disembarking Irish immigrants. As Tweed tries to convince “Bill the Butcher” of the political utility of immigrants to the Tammany machine, Cutting asserts the right to “protect” the United States from immigrants because his “father gave his life making this country what it is, murdered by the British, with all of his men, July 23, 1814.” Cutting’s father, then, died during an American offensive in lower Canada at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, the bloodiest battle of the war, in which American troops failed to take an entrenched British position in a battle so intense that it reportedly almost drowned out the sound of Niagara Falls, and General Winfield Scott, the man who would one day be nicknamed “The Grand Old Man of the Army,” was injured so badly that he was out of action for the rest of the war.

If contemporary popular culture has ignored this conflict, however, what about the popular culture of its own day? In particular, what about the theater, which owing to the frequency of its productions was the most politically flexible of early American art forms? As Alexis de Tocqueville would later note of the American theater and theaters in democratic societies more generally, the theater offered a unique insight into the minds of the people since theatergoers in those countries went to plays in order to see people like themselves who shared their own concerns, and to hear their own opinions represented. Patriotic sentiments were, at the very least, good marketing. Such sentiments had been, moreover, commonplace in the first theaters established in the American colonies between the late 1740s and the early 1770s. Beginning with a few scrappy colonials and one or two companies of hardy touring players from the British metropole, over the course of two decades a few acting companies built a touring circuit extending from Charleston to New York where theater enthusiasts could go to see old warhorses like Joseph Addison’s Cato (1713) and newer works such as Richard Cumberland’s romantic comedy The West Indian (1771). Effusions of British patriotism were commonplace on the colonial stage both in the plays and in the prologues and epilogues that framed them, fitting for a medium that was championed by its eighteenth-century fans as a vehicle for moral and civic education. The very act of playgoing, to its champions, was a way of asserting one’s own Britishness, especially when one might never set foot in Great Britain itself. Touring companies, most notably the London Company of Comedians, who arrived at Williamsburg in 1752 and came to hold an effective monopoly on the theater business, tweaked their offerings to suit contemporary tastes in patriotic entertainment, even when those tastes underwent major shifts. In the wake of the Stamp Act Crisis of the mid-1760s, for instance, the London Company of Comedians changed its name to the American Company of Comedians. The nascent theater industry held a privileged position in colonial culture and was almost uniquely positioned to track the shifts in the national self-image of Americans throughout the mid- and late eighteenth century.

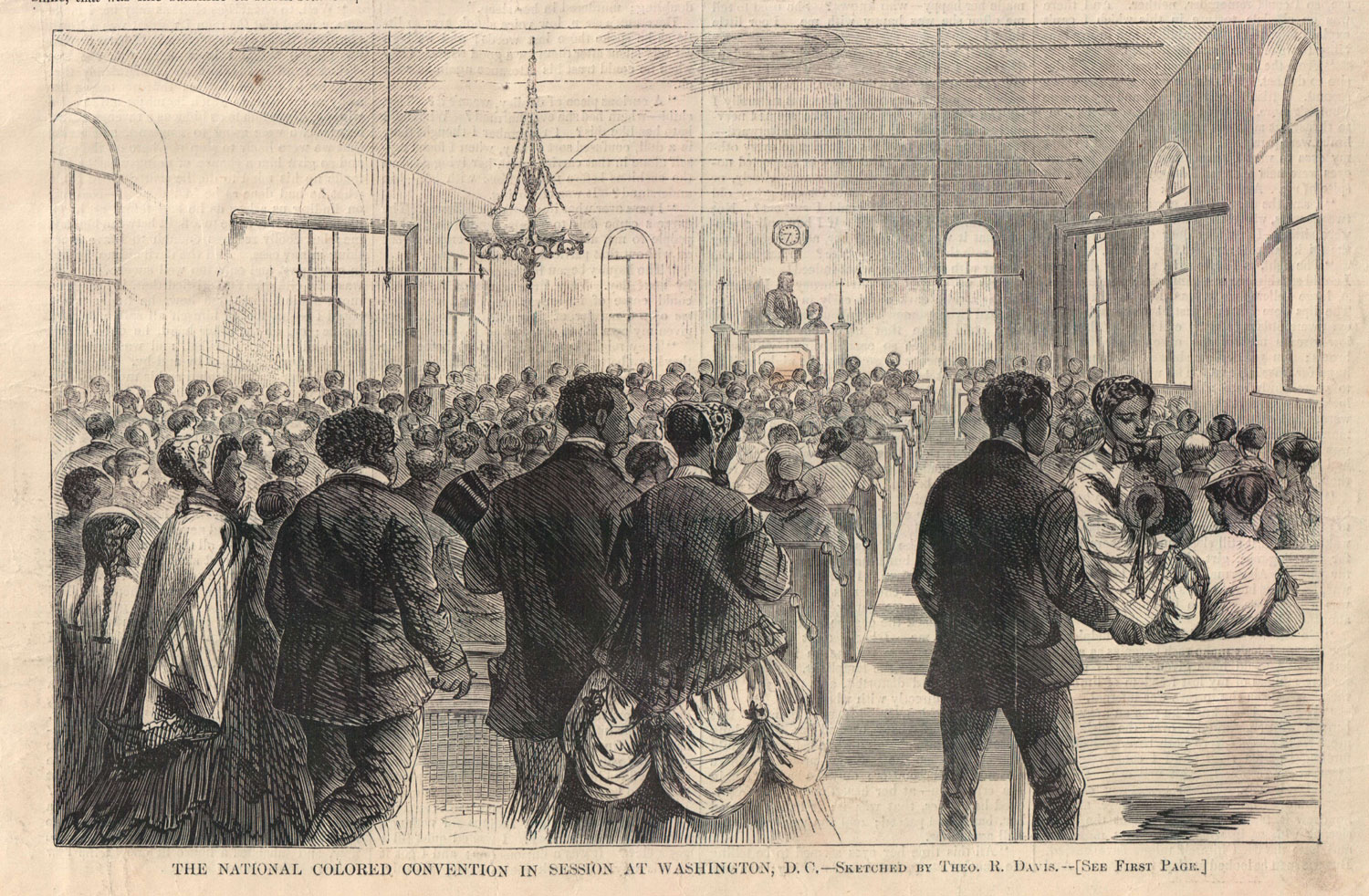

As in the eighteenth century, so in the nineteenth. In the preface to his 1819 play She Would Be a Soldier, which centers on the 1814 battle of Chippewa, the American playwright, newspaperman, and diplomat Mordecai Noah declared that plays on patriotic topics “ought to be encouraged” because “they keep alive the recollection of important events, by representing them in a manner both natural and alluring.” Noah, however, wrote from a peacetime, commemorative perspective. What of the war years themselves? During the American Revolution, professional theaters were shuttered by a 1774 congressional ban on public frivolities, but amateur playwrights representing a variety of political perspectives converted current events into a number of stirring propaganda plays based on major battles. In the mid-1780’s actors from the American Company, who had weathered the war in Jamaica, began returning to their old haunts and applying for permission to set up shop in new theaters, which in most cases was granted, albeit grudgingly at times. With the young republic’s theaters generally open for business during the War of 1812, were American audiences likewise treated to theatrical news from the front?

The answer is both yes and no. The incentives for such “ripped from the headlines” productions were limited, not only because of the strictures of a wartime economy but also because of the structure of the budding American theater business. In the colonial period, traveling companies had worked their way up and down the coast, playing “seasons” that could range from a night to several months in a given city before moving on. The earliest post-independence theater troupes tended to split up the territory of the United States by forming residential companies in major cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, playing long seasons in residence supported by modest regional tours. (Boston, long a bastion of Puritan hostility to professional theater, finally licensed a theater in 1794.) Initially these regional monopolies focused on the task of cultivating a renewed public appetite for theatrical entertainment, a task that frequently involved brief nods to American patriotism in the form of occasional prologues or songs. As the public’s appetite grew, new theaters opened up in Providence and Richmond, and competing companies sprang up in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. Yet while American playwrights and some early theater critics in the newspapers advocated a more distinctly “American” theater, relatively few plays on national topics emerged.

In part, this was so because managers rarely wanted to invest the limited time (and memory) of their performers learning unproven new roles. Also, the United States afforded little to no copyright protection to foreign authors, so those in this already high-risk business had little reason to pay for new plays by Americans when new British plays and old standbys could be had for the price of a script. The American theater, moreover, remained heavily dependent on the country’s relationship with Britain since almost all of the actors in the early United States had been born in Britain or Ireland. Well into the nineteenth century, American audiences still clamored to see new plays from London and their old favorites, so the theatrical repertoire remained centered on British imports such as Shakespeare (whom many Americans thought of almost as one of their own), Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s late-eighteenth-century comedies of manners, and potboilers like Thomas Otway’s Venice Preserved, a Restoration drama brimming with political and sexual conspiracies. Adding to the difficulty of producing new plays, in the 1790s American theaters began making a transition from residential companies that featured their own leading actors to the “star system,” where the most profitable seasons were built around touring star actors who moved between companies, generally playing leading roles from repertory plays.

Fortunately, a night at the theater during the War of 1812 did have other attractions besides the main piece, and those other features offered better opportunities for topical entertainment. Indeed, if the American theater’s repertoire of full-length plays remained rather unaffected by current events, the catalog of peripheral performances that surrounded them appear to have shifted with every prevailing wind of public sentiment. Theaters generally performed a “farce,” a short one-act comedy that often featured songs and dancing, after the conclusion of the main piece. And faced with growing competition from circuses and other diversions, theaters began experimenting with additional songs and entertainments, as well as illuminations (light displays) and displays of paintings or panoramas of contemporary subjects. The market for afterpieces and short entertainments allowed the news of the day to penetrate the walls of the theater and mount the stage as theaters enticed their patrons with not only their old favorites, but also with lively celebrations of American victories. While relatively few of these pieces were eventually collected and issued in print, the newspapers of the period are full of theatrical advertisements and occasional commentary on recent developments in the theater, providing us with an invaluable archive of performance schedules, occasional reviews, and gossip about the performers of the day, especially the stars or those actors who hoped to become stars. In 1787, for instance, fans of the three leading ladies of New York’s Old American Company engaged in a paper war over the relative merits of their favorite actresses. The preferred weapons of these partisans, letters to the editor of the Daily Advertiser, convey such a sense of urgency and personal animosity that one might be tempted to overlook the reports from the Constitutional Convention running in the same newspaper and assume that this theatrical judgment of Paris was the most pressing matter in the nation.

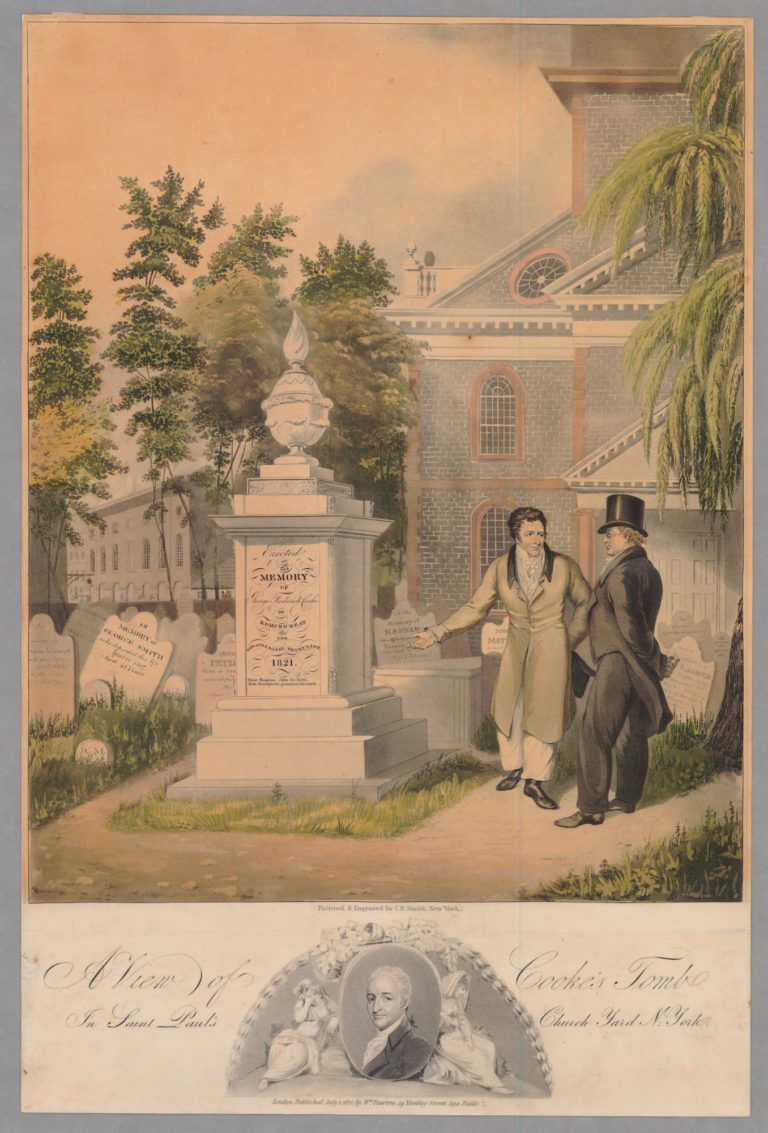

In the decades leading up to the United States’ declaration of war on Great Britain in June of 1812, then, the American theater was not as a rule obsessed with current events, but this is not to say that the stage was entirely devoid of topical, patriotic entertainment. (For those interested in topical goings-on north of the border, sadly, scholarship on the early Canadian theater is still somewhat lacking.) In 1807 the Philadelphia dramatist James Nelson Barker (who would go on to serve as an artillery officer in the War of 1812) produced a satire on the United States’ embargo against British and French trade, The Embargo; or, What News?, although the play met with limited commercial success and was never printed. (Barker himself described it as a very derivative piece and seemed to be relieved that it was never printed.) In 1811 the Boston theater produced James Ellison’s The American Captive; or, the Siege of Tripoli. Some British-born actors had become American citizens and joined in the nation’s occasional outbursts of cultural boosterism. Among these was the first genuine star on the American stage, Thomas Abthorpe Cooper, who was the foster son of the radical British novelist and journalist William Godwin. In both general terms and also specifically in the context of the War of 1812, historian William Clapp says, Cooper “rejoiced in the success of his adopted country.” Nonetheless, during the first decade of the nineteenth century, the single greatest development in the American theater was the widespread popularity of European melodrama, especially translations of the German playwright August von Kotzebue made by the theater manager, playwright, and theater historian William Dunlap. Dunlap would also go on to write the definitive memoir of the most prominent star of the 1812 era, the British actor George Frederick Cooke (fig. 1), whose own sympathies were decidedly not pro-American.

Cooke’s history as a performer in the United States at a time of heightened international tensions reminds us not only that the early American theater was heavily dependent on British talent, but also that in many cases early American audiences were less concerned with the patriotic appeal of a performance than its artistic quality. Cooke, a leading man in the British theater who had a reputation for dipsomania equivalent to his talent and had thus earned a reputation for unreliability, was signed in 1810 by Cooper during one of the latter’s periodic recruiting forays back to his birth country. Making the transatlantic journey without alcohol at his disposal, Cooke landed in New York on November 16, 1810. Despite the heightened international tensions prevailing between the United States and both Britain and France, Dunlap recounts that Cooke’s arrival “caused a greater sensation, than the arrival of any individual not connected with the political welfare of the country.” Cooke, whose performances during his tour of the United States between 1810 and early 1812 most notably featured his performances of Richard III (the role for which he was most famous), Shylock, and Iago, received, effectively, a royal welcome. Dunlap describes his entrance to the stage in his inaugural New York performance as Richard III in tones that suggest not only the actor’s transformation into his role but also the audience’s transformation into the performer’s subjects:

He returned the salutes of the audience, not as a player to the public upon whom he depended, but as a victorious prince, acknowledging the acclamations of the populace upon his return from a successful campaign—as Richard Duke of Gloucester, the most valiant branch of the triumphant house of York.

Cooke quickly became a sensation. One spectator of his Richard called all previous theatrical exhibitions in the United States “boy’s play to this night’s exhibition.”

Not all of his performances in the United States would go so smoothly. On December 19, 1810, for his New York benefit night, in which the house’s profits went directly to the star, Cooke chose Joseph Addison’s 1713 neoclassical tragedy Cato. The most popular play in the colonial era, Cato was approved of and quoted even by people who viewed the theater as immoral. Although he had played the role before, Cooke spent the day drinking rather than rehearsing, and as a result, according to the New York Journal‘s review on December 22, he “hesitated, repeated, substituted speeches from other plays, or endeavored to substitute incoherencies of his own.” Receipts dropped off for the rest of his New York engagement. When Cooke moved on to Boston in January 1811, his welcome was somewhat soured by the attacks of a local newspaper, the Independent Chronicle, which decried the city’s disregarding important national and international affairs while lavishing so much attention on the theater that Cooke could “get five or six hundred dollars an evening for repeating over the unnatural phrenzies of Shakespear[e] in his character of Richard IIId.” Perhaps the most intriguing thing about Cooke’s performance, however, was that he gained such popularity during a period of such great diplomatic tension given his tendency to revisit the topic of American independence in unsparing terms.

William Dunlap, in his memoir of Cooke, records a series of outrageous anecdotes involving Cooke’s relationship with his American hosts. The most famous one involves an 1811 performance in Baltimore, before which Cooke was informed that President Madison intended to travel from Washington to see him act. Dunlap reports that Cooke burst out “What! I! George Frederick Cooke! who have acted before the majesty of Britain, play before your yankee president!” and threatened to cancel the performance by informing the audience that “it is degradation enough to play before rebels; but I’ll not go on for the amusement of a king of rebels, the contemptible king of the yankee doodles!” Equally outrageous to his companions was Cooke’s tendency to portray himself as a veteran British campaigner who had served during the Revolution. Dunlap recalls one episode in New York where Cooke claimed he had led the British advance in the Battle of Brooklyn, and that if Lord Howe had not called off the advance “I should have taken Washington, and there would have been an end to the rebellion!” Likewise, during a sojourn in Boston, he provided a vivid (and false) account of his participation in the Battle of Breed’s (Bunker) Hill. Ironically, as the United States drifted toward a second war with Great Britain, the biggest sensation on its stages was a British actor with an unfortunate offstage habit of reliving the previous one.

The United States officially declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. By this time President James Madison’s would-be theatrical rival Cooke had already booked passage back to London to begin an engagement at the Covent Garden Theatre. Years of alcoholism had taken their toll on his health, however, and he played his last ever performance in Providence on July 7, as the scheming Sir Giles Overreach in Philip Massinger’s Jacobean tragedy A New Way to Pay Old Debts. He died on September 26 in New York and was buried in St. Paul’s churchyard (now opposite Ground Zero), where in 1821 the British actor Edmund Kean erected a memorial to him (fig. 2). As Cooke sickened and died, the tenor of the theaters (and nation) whose attention he had drawn since 1810 changed markedly.

In order to see the potential effect that the War of 1812 could at times have on the American theater, one need only look at the program for July 4, 1812, at the Park Theatre in New York, where Cooke had debuted as Richard III. American theaters normally recognized July 4 with brief patriotic songs or speeches in the early nineteenth century, but in 1812 the holiday produced an extravaganza. According to an advertisement in the July 3, 1812, edition of the New York newspaper The Columbian, the Park resurrected a patriotic tragedy of strongly Democratic-Republican leanings, John Daly Burk’s 1797 Bunker Hill, Or the Death of General Warren. The ad promises a transparent painting of the allegorical figure of Liberty holding an olive branch and the American flag while three young boys stand to one side reading the Declaration of Independence. During the play (acted “for the first time these seven years”), the ad describes in detail, audiences will see in the fifth act the funeral of General Joseph Warren, featuring banners declaring “The Rights of Man,” “Liberty or Death,” and other patriotic slogans, and a grand fantasia involving a statue of George Washington and allegorical representations of the Genius of Liberty and the Genius of America. Following the main play, the ad promises two patriotic songs, including a description of the 1811 pre-war skirmish between the USS President and the HMS Little Belt, and a farce resurrected from war with the Barbary Pirates to be followed by more patriotic songs and a finale featuring (again) the Genius of America and a display of the names of American naval heroes on two giant columns. While no other night of theater during the war quite equaled this smorgasbord of patriotic entertainment, each form of entertainment caught on with wartime theatergoers.

Naval victories produced a particular thrill in the theater, one no doubt enhanced by the improving quality of theatrical scene-painting. After the USS Constitution defeated the HMS Guerrière on August 19, 1812, the Constitution, indeed, became something of a theatrical craze. When news of the victory reached Cooper in Boston, he announced it to the audience. By October 2, the theater in Boston had pulled together a short play titled “The Constitution and Guerrière,” which included a scene of the British warship’s surrender and concluded with a presentation of the colors. A few days earlier in Philadelphia, on September 28, the Olympic Theatre had presented, according to an ad in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, a short opera called “The Constitution, or American Tars Triumphant” that had included “a Grand Naval Column” and a transparency of Captain Isaac Hull, commander of the Constitution. (The show the following night closed with a sailor’s hornpipe.) On April 9, 1813, the ship’s crew themselves became part of the spectacle when they attended the theater in Boston, in honor of which the theater was illuminated.

The most successful theatrical text of the war’s first year, however, was the work of William Dunlap, the former manager of the Park Theatre, for his old institution. On the opening evening of the 1812 season, September 7, the Park followed the romantic tragedy of Abaellino with a musical sketch by Dunlap, “Yankee Chronology.” (One of Dunlap’s earlier works, a patriotic mélange of songs and speeches called The Glory of Columbia! Her Yeomanry, had been played earlier in the year at both New York and Providence.) The short sketch revolved around the return home to New York of a young sailor, Ben Bundle, who recounts for his father and their Irish neighbor, O’Blunder, the story of his adventures at sea. A former merchant sailor who was impressed by the British, escaped, and upon landing at Boston immediately signed on with the Constitution, Ben unfolds his heroic journey and the Constitution‘s victory to his father. Ben concludes the piece with a song that constructs a genealogy of American liberty running from colonial settlement through the Revolution and concluding with the defeat of the Guerrière, each verse offering the audience the chance to belt out “Huzzah!” before Ben continues to the next historical episode. Dunlap’s sketch was acted throughout the fall and early winter in New York, including on Evacuation Day (for which Dunlap wrote a new verse), and the play was printed and widely advertised—a rarity for such occasional texts during the war.

While few victories got their own sketches by perhaps the most prolific playwright of the early United States, such celebrations became a commonplace for the duration of the war. After Perry’s victory at the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, the Park illuminated its house to honor the victory. On October 6 audiences were treated to a song in honor of Perry. In the ensuing months the house was illuminated again as the theater was patronized by General William Henry Harrison, commander of American land forces in the west, and Commodore Stephen Bainbridge, Hull’s successor as commander of the Constitution. In Philadelphia on October 9, the Olympic Theatre hosted a circus in honor of Perry’s victory, including a display of the battle setting and a recitation by the actor James Fennell of his poem dedicated to Perry, “The Hero of the Lake.” (Fennell repeated the performance in December when Harrison attended the Olympic.) In Boston, the theater produced a short play on October 9, “Heroes of the Lake; or, The Glorious Tenth of September,” and when Perry visited Boston on May 9, 1814, the theater staged not only the popular British comedy The Sailor’s Daughter but also a “Naval Fete” and a series of patriotic songs to celebrate Perry’s heroism.

Not everyone appreciated these spectacles. The Stranger, a small literary gazette in Albany, New York, reviewed a farce celebrating the victory at Lake Erie on February 26, 1814, and found it composed of “barbarous rhymes, unconnected circumstances, partial dialogue from various sources and unfinished allegory tacked together.” Indeed, with events such as a crisis in public credit and the British campaign in the Chesapeake that culminated in the burning of Washington on August 29, the year offered little enough by way of celebration for the American public, even with major American victories at Baltimore and Lake Champlain. As George C.D. Odell, the great historian of the New York theater, observes, “the public wound was too deep” to be salved with entertainment. In New York the mixed mood of the theatrical public is evident in the season’s offerings. On August 29, the day the British were burning Washington, a new theater company in New York housed in Anthony Street put on Bunker Hill; the Park resurrected Dunlap’s farrago The Glory of Columbia. The remainder of the season featured the classic mix of reportorial British main pieces with what Odell calls “hasty patriotic ebullitions” to celebrate moments like the American naval victory at Lake Champlain on September 11, 1814. At such moments, however, the irony seems heightened. When Winfield Scott arrived in New York in September 1814, the Park illuminated the house and hauled up a transparency “in honor of The Hero of Chippewa,” but the night’s main entertainment was Sheridan’s The Rivals, not a celebration of American heroism. Small wonder, perhaps, that theater managers were so grateful for the arrival of news of the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, which was widely greeted with theatrical displays of song and dance, as in Boston, and of good old reliable allegory, as in a “Festival of Peace, or Commerce Restored” featuring the Genius of Columbia at the Park in New York. With peace, the theater business could get back to normal.

The War of 1812 did not end on the battlefield with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814. Hostilities continued into the new year, most notably with Andrew Jackson’s victory at New Orleans on January 8, 1815. New Orleans became the most celebrated event of the war, one that made Jackson not only a military (and later political) hero but in some measure also a theatrical celebrity. The years from the conclusion of the war to the beginning of Jackson’s presidency in 1829 saw a number of new plays by American authors celebrating American achievements from the War of 1812. Some, such as Noah’s She Would Be a Soldier, were only nominally about the battles; Noah’s main plot follows a young woman who dresses as a man and enlists to follow her lover to the battle at Chippewa, while the battle occurs offstage. Even in plays such as 1830’s Triumph at Plattsburg, a heroic play about the Battle of Lake Champlain written by the Philadelphia attorney and playwright Richard Penn Smith, the audiences saw most of the battle through dioramic naval scenes depicted in a large window in the set. In the case of Jackson’s victory at New Orleans, however, Jackson himself was often the center of the spectacle.

The figure of Jackson enlivened the postwar theater, which in the wake of the war did occasionally seem to be running out of ideas. On July 4, 1816, the Park Theatre dusted off the same transparency of Liberty and the three reading boys that they had first displayed on July 4, 1812, shortly after the declaration of war. The theater’s ad in the New York Courier described a very different main piece, however. Rather than exhuming a depiction of revolutionary heroics, the Park offered C.E. Grice’s The Battle of New Orleans, a romantic drama in which Jackson himself is a character. This onstage Jackson acts as not only a military commander but also the arbiter of justice in the romantic entanglements of his young subordinate officers and closes the show by declaring that “Duty and beauty are Columbia’s shield.” (As if in fairness to the Navy, the show in New York closed with a sailor’s hornpipe as an afterpiece.) Jackson’s electoral (rather than military) campaigns in 1824 and 1828 led to further such productions, including Old Hickory; or, A Day in New Orleans (1825) and Andrew Jackson (1828). The latter featured Jackson receiving, but not donning, a crown of laurels, a la Julius Caesar. Jackson’s career as a theatrical spectacle culminated in 1829 with Smith’s The Eighth of January, a play mounted hurriedly, according to its author, in order to be staged on January 8 of that year as a celebration of Jackson’s election.

Smith’s Jackson portrays the sort of neoclassical image of American martial heroism popular at the time, but he also flashes a distinct flair for romantic derring-do by venturing behind enemy lines in disguise before being wounded and captured. Smith (whose grandfather William Smith was stripped of his title as chaplain to the Continental Congress on suspicion of Toryism) scatters a series of honorable British characters throughout the play, including the British-born miller John Bull (whose son is an officer under Jackson) and the Scottish Captain M’Fuse. Many of these Britons find a way to make peace with Jackson at the play’s end when he shows mercy and generosity toward them, bonding over a shared belief in honor and liberty. Jackson serves as an onstage emblem of both martial civility and respect for the common man. He earns the respect of his British enemies for his noble bearing while also delivering a victory speech saluting the “freemen and fathers of families” of the mixed American forces at New Orleans, “the brave yeomen who comprise my army.” While Smith’s Jackson clearly toes a Jacksonian line on domestic politics, Jackson’s forbearance to the British in Smith’s script also ironically prefigures the relatively conciliatory foreign policy that Jackson, as president, would pursue with Great Britain despite his military record and the lingering policy disputes under previous administrations such as the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine and the tariff of 1828. At least in the theater, the War of 1812 officially ended in 1829 with a restoration of comity between the United States and Britain in the form of the new king of the yankee doodles, Andrew Jackson.

Further Reading

For more on the War of 1812, see Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, Bicentennial Edition (Urbana, Ill., 2012); Hugh Howard, Mr. And Mrs. Madison’s War: America’s First Couple and the Second War of Independence (New York, 2012); Mark Collins Jenkins, The War of 1812 and the Rise of the U.S. Navy (Washington, D.C., 2012); Alan R. Taylor, The War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels & Indian Allies (New York, 2012).

For the history of the American theater before and during the War of 1812, see William W. Clapp, A Record of the Boston Stage (Boston, 1853); William Dunlap, History of the American Theatre (1832; Urbana and Chicago, 2005); Walter J. Meserve, An Emerging Entertainment: The Drama of the American People to 1828 (Bloomington, 1977); George C.D. Odell, Annals of the New York Stage (New York, 1927); Jason Shaffer, Performing Patriotism: National Identity in the Colonial and Revolutionary American Theater (Philadelphia, 2007).

For the history of George Frederick Cooke, see William Dunlap, Memoirs of George Frederick Cooke, Esq. 2 vols. (London, 1813); Donald B. Wilmeth, George Frederick Cooke: Machiavel of the American Stage (Westport, Conn., 1980).

This article originally appeared in issue 13.1 (October, 2012).

![Fig. 5. "Women will Purify the Ballot Box—Shakspere [ sic ]." Front cover of Phunny Phellow 10:1 (December 1869). Courtesy of the Collection of Richard West/Periodyssey.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/7.3.Bunker.5-222x300.jpg)