Print Culture and Popular History in the Era of the U.S.-Mexican War

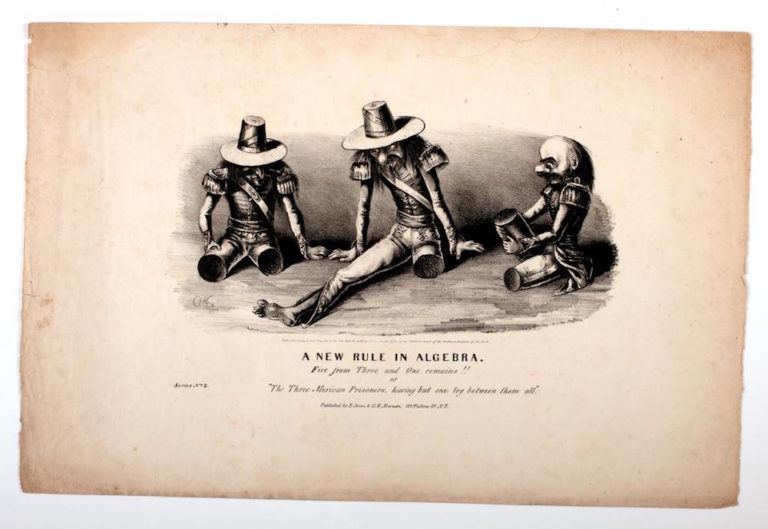

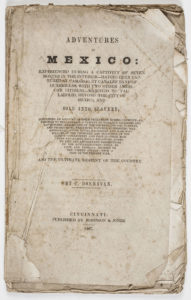

As a Latino scholar who recently completed a year-long postdoctoral fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society, I can’t approach researching the 1846 U.S. invasion of Mexico without being reminded of how the print archive preserves evidence of nineteenth-century racism that resonates with contemporary U.S.-Mexico relations. Consider this statement from Corydon Donnavan’s 1847 book Adventures in Mexico: “The fact need not be concealed, that from their meanest soldier to their best general, [the Mexicans] are a nation of liars and plunderers. There are a few honorable exceptions, it is true, but more modest epithets will not serve truly to portray their general character.” Mid-nineteenth-century American popular culture frequently made such claims, ascribing lawlessness and immorality to the Mexican people. The present essay offers some archival discoveries that show how American publishers played an active role in shaping portrayals of the Mexican War in U.S. print culture, in particular, by censoring the writings of U.S. soldiers before they appeared in the print public sphere. As we will see, some authors and publishers edited manuscripts before publication to remove evidence of illicit activity by the American military. In other cases, print itself was marshaled as evidence of U.S. superiority and Latin American underdevelopment.

While the origins of wide-scale U.S. racism against its southern neighbor can be dated to the Texas Revolution (1835-36), the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-48) was better able to mobilize popular print culture due to the newly industrialized book trade and emerging technologies that produced visual culture on a larger scale. The conflict provided the American army with a foreign war that doubled as exotic travel for volunteer soldiers, many of whom strongly identified with their Anglo-Saxon roots. Soldiers spread their assessments of Mexican culture in media formats that ranged from newspapers and printed books to lithographs, daguerreotypes, and moving panoramas.

A remarkable amount of writing produced by the American soldiery documents their experiences. More entrepreneurial souls like Corydon Donnavan (described in more detail below) wrote books, gave public lectures, and charged admissions to panorama exhibitions. In print and manuscript, soldiers made countless racist observations that were inflected by perceptions of Mexican political institutions, society, cuisine, and gender identities. For instance, Robert Armstrong, aid to General Winfield Scott, wrote his sister that the Mexican people are “totally incapable of self government,” blaming Catholicism for ruining their political system. Furthermore, many U.S. soldiers were avidly on the prowl for sex. Complaining of having few responsibilities to occupy his time, since fighting was infrequent, C.B. Ogburn wrote about the “Saltillo girls” who inspired him to engage in as many “tall sprees” as he could manage. Other soldiers were fascinated by vestiges of pre-Columbian history. The Lieutenant John Wolcott Phelps paid Mexican children to gather stone fragments from the pyramid at Cholula: “The latter always occurring in such a shape as to leave no doubt but that they are the broken and worn out knives which were used in the sacrifices.” Military officers such as Phelps recorded their observations in diaries as well as letters, which were often excerpted for publication in American newspapers; Mexican souvenirs sometimes were mailed home with this correspondence as well.

The U.S. invasion was culturally defined by this “scribbling soldiery,” a term used by the New York periodical Yankee Doodle in 1846 to describe the phenomenon of the soldier-turned-amateur author. My research has been illuminated by considering the original editions of soldiers’ narratives from collections held by the American Antiquarian Society and other institutions. In particular, I’ve been drawn to a hitherto unstudied pattern of erasure and omission of detail in published accounts, where the publishers and editors of these soldier-authors seem to deliberately omit the violence of the war. Modern scholars such as Robert Johannsen, Shelley Streeby, and Paul Foos have previously studied these Mexican War narratives, from cheap fiction by George Lippard and Ned Buntline to personal histories such as 1847’s Camp Life of a Volunteer. Novels such as Legends of Mexico (1847) and ’Bel of Prairie Eden (1848) helped justify the war to popular audiences by casting a narrative of Anglo-Saxon superiority over Mexico’s mixed-race population and weak level of state-formation. As ’Bel of Prairie Eden’s John Grywin put it: “Fifty white men of Texas are equivalent to one thousand Mexicans, any day.” Less noticed is the fact that Lippard’s texts themselves located authenticity in manuscript narratives of the Mexican War. ’Bel of Prairie Eden, for instance, drew from a fictional manuscript written by a “Soldier of Monterey.” Authors of fiction used the conceit of the “real” manuscript (even if they were making it up), just as popular accounts came from soldier diaries and letters. But manuscripts from the war didn’t appear in print without careful editing. By implication, it is the mediations between manuscript and print—the transmission from one medium to the other—that revealed the ideological constraints that made some perspectives on the war invisible to the public.

Paul Foos observes in his 2002 study A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair that many published personal narratives from the Mexican War are curiously silent regarding the conflict’s violence. American soldiers largely refrained from considering the moral implications of a military invasion against a poorly organized enemy. That said, my bibliographic analysis of the transmission of manuscript into print clarifies the ideological function of the war’s literature. In at least three instances, archival evidence proves that American publishers carefully edited soldier narratives to omit information that might contradict the war’s nationalist justification. For example, Camp Life of a Volunteer—a widely read history described by the historian Robert Johannsen as a “straight forward journal”—is anything but truthful. The University of Texas, Arlington, possesses the manuscript diaries of the soldier Benjamin Franklin Scribner that formed the source material for Camp Life of a Volunteer. On a recent visit to Arlington, I conducted a line-by-line textual comparison of the manuscript with the printed edition and found numerous divergences. Camp Life’s publisher (Philadelphia’s Grigg, Elliott, & Co.) omitted passages unfavorable to the military. Scribner’s reflections on his moral failings—moments of doubt and confusion regarding the war’s justification—were omitted from the published edition. American readers were never able to read that Scribner felt he was “acting a part in which my own character is not represented,” or that he had “dipped into all the temptations that have come in my way.” This latter statement offers a rare suggestion of the illicit activities of the U.S. military perpetrated upon the Mexican people. At the same time, because of the censorship, American readers never learned that Scribner occasionally wrote about how he abhorred the war, that he felt “alone and desolate in my social relations,” and concluded that in Mexico “the future has nothing in store for me.” Without these crucial statements, the voice of Camp Life of a Volunteer had a more tenuous relation to the manuscript sources than readers were led to believe. Grigg, Elliot, & Co. thus distributed a war narrative that sanitized Scribner’s account in such a way as to minimize political controversy and conceal evidence that U.S. soldiers were not always behaving their best.

When transformed into books, manuscript sources were carefully edited to suit the interests of publishers hungry to satisfy the print market. Consider a second example. In 1849, South Carolina’s H. Judge Moore published a personal history entitled Scott’s Campaign in Mexico, which sought to give greater credit for Southern distinction in the American victories led by Winfield Scott. Although Moore presented himself as writing with a “free and impartial hand, and an unbiased head,” comparison with his manuscript diary (held by Yale’s Beinecke Library) reveals a similar pattern of selective memory. For instance, missing from the printed version is Moore’s desire to “see a Mexican Donna” and “claim the promise made to Abraham that my seed should possess the land.” Moore’s published book therefore focused on the details of battle at the expense of the more complicated sexual factors that shaped his experience of the war. Such examples reveal the rhetorical frames that foregrounded particular experiences over others deemed less favorable or marketable. The project of nineteenth-century American autobiography, which historian Ann Fabian has summarized as the writing of a “plain, unvarnished tale,” proves in the Mexican War histories to be anything but plain or truthful.

Consider a third case of doctored narrative: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s notorious campaign biography of his friend Franklin Pierce. Just in time for the 1852 election, Hawthorne aided Pierce’s bid for the presidency by writing a “political biography” whose intimate knowledge of the man derived from a friendship that began when both were students at Bowdoin College. Despite Hawthorne’s claim of impartiality, the author clearly manipulated the facts to represent Pierce as a hero of the Mexican War. In a decisive act of editorial manipulation, Hawthorne reproduced Pierce’s war diary as Chapter IV of the Life of Franklin Pierce. The author framed Pierce’s account by presenting it as authentic documentation: “They are mere hasty jottings-down in camp … but will doubtless bring the reader closer to the man than any narrative which we could substitute.” Hawthorne wished to bring the reader closer, but not too close. In fact, several crucial entries from Pierce’s Mexican diary were deliberately omitted from the biography published by Ticknor, Reed, and Fields.

It is worthwhile to understand Hawthorne’s act of message crafting as a later instance of the framing techniques and editorial strategies used in Camp Life of a Volunteer and Scott’s Campaign in Mexico. One passage Hawthorne chose not to include from Pierce’s camp writings is quite interesting; here Pierce writes for a need for ruthless military prosecution: “War, that actually carries, widespread woe & despoliation to the conquered and tacitly at least, allows pillage & plunder with accompaniments not even to be named during a campaign like this even in a private journal.” Obviously, this statement just wouldn’t do in a contested political campaign. And in a more subtle way, passages of this kind from Pierce’s diary dramatically undermine the ideological coherence of the U.S. invasion by suggesting that the American military allowed and implicitly promoted “pillage & plunder with accompaniments not even to be named.” Like the diaries of H. Judge Moore and B.F. Scribner, Franklin Pierce’s manuscript hints at aspects of the U.S. military invasion that might be described as war crimes. That said, these are only hints—literary expressions of sexuality, plunder, violence, and martial manhood—that cannot be precisely documented. Because Hawthorne’s Life of Franklin Pierce silenced these ambiguities of Pierce’s wartime experiences by leaving them out of the publication altogether, the campaign biography exemplifies the larger effort by American publishers to obscure the war’s history.

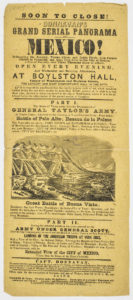

One printer turned public lecturer, Corydon Donnavan, asserted the dominance of American society over Mexico’s underdeveloped institutions by directly contrasting the printing trades—a purported marker of progress—of both nations. At the war’s outset, Donnavan worked as a clerk in the steamboat business, but he later monetized his experiences in Mexico when he became a public showman and exhibitor of moving panoramas in Cincinnati, Boston, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Here we see how sensational reading about the war operated within a broader media environment, as Donnavan used his panorama shows as promotional opportunities to sell Adventures in Mexico. A broadside for performances in Boston summarizes Donnavan’s multi-medial combination of panorama, oratory, and bookselling: “For several months a prisoner during the recent war in that country, will deliver an Explanatory Discourse, relating many incidents of the war, Mexican Life, Manners &c., as the Painting passes before the audience. His ‘Adventures in Mexico,’ a work of 132 pages, including an appendix descriptive of the Panorama, may be had at the Hall.” Among other events, the book made much of his capture in 1846 by a group of Mexican bandits, who sold Donnavan and several other men into slavery.

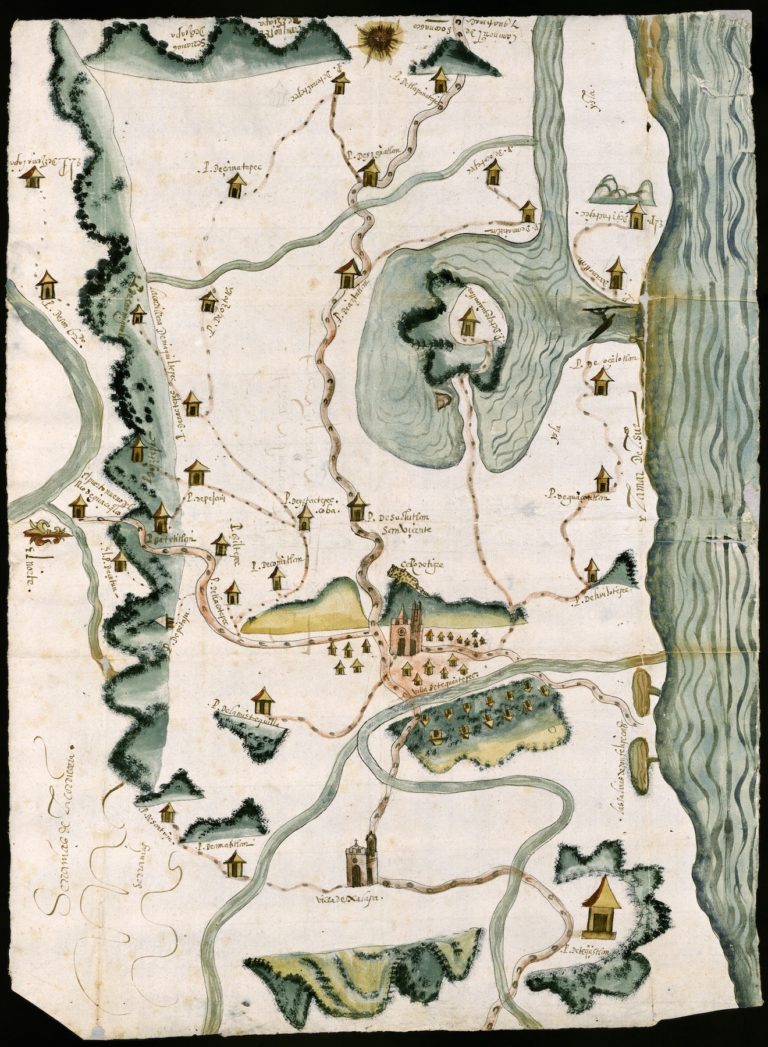

As recounted in Adventures in Mexico, the captors spared the Americans’ life when Donnavan explained that his fellow prisoners were job printers and not U.S. soldiers. In response, the bandit Poco Llama decided to sell the men as labor in a Mexican printing office. The captives were then taken from Camargo on a long march through Coahuila stretching from Monclova to Parras. From there Donnavan and company were taken farther south to Sombrerete, to Fresnillo, and finally to modern-day Zacatecas (then known as Valladolid). While some parts of the story are undoubtedly fictionalized, even the imaginary aspects of Donnavan’s tale contain their own explanatory power, insofar as Adventures in Mexico offers another index of the various ways U.S. print culture conjured its Mexican enemy as the opposite of democratic modernity. In particular, Donnavan focused on a printing press as the symbol of Mexico’s postcolonial underdevelopment. Here is his description of a decrepit hand press used to print newspapers in Valladolid:

In printing, as well as other arts, mechanics, and agriculture, the Mexican people are at least two centuries behind the age. Their type and presses, like their muskets, are generally the worn out and cast-off material from England. The old Ramage presses were so venerable they could scarcely stand alone, and at each successive revolution of the rounce their shrieks would grate upon the ear, as if exercise was as painful to them as to the Spanish printers who were torturing their old joints.

There’s a bit of irony here: Ramage presses were actually relatively recent, first sold by Adam Ramage from Philadelphia in 1800. But the larger point made by Donnavan contrasts the print modernity of the United States (the nation’s steam presses, stereotyping plants, paper factories, etc.) with the backwardness of a Mexican newspaper still locked in the hand press era. Print technology, in other words, was the vehicle for Donnavan’s racist bias. He was especially insulted that the Mexican printers set type while sitting down: “The cases, instead of being mounted on stands, are spread out on the floor, as the Spaniard, being too lazy to take a perpendicular position, prefers to sit down to set up type; and on a filthy mat, thrown out upon the floor, he sprawls himself at his occupation, where he will sometimes succeed in setting three thousand em’s per day.” Punning on the homonym sit/set, Donnavan draws a seamless connection between backwards print technology and backwards printing practice. Surely a nation that lazily sits down to set type, rather than standing at an orderly type case, doesn’t have the political will to exercise sovereignty. If, as U.S. politicians suggested, Mexico didn’t have a functioning republic, then it stands to reason that part of that dismissal is rooted in values similar to Donnavan’s claim that Mexican printing, “as well as other arts, mechanics, and agriculture,” are obsolete by several centuries.

But Donnavan’s disgust at bad printing turns out to be misplaced. First, we should note that Ramage presses were produced in the United States, and therefore Donnavan ends up chastising Mexican print culture for striving to resemble its northern neighbor. But the Ramage press was not the only irony. Despite his accusation that Mexican printing is riddled with mistakes, the first edition of Adventures of Mexico erroneously lists its year of publication as 1487. The supposedly superior printing abilities of the American press produced the first edition of Adventures of Mexico with a glaring printer’s error right on the title page. In the process of arguing that the printing press itself distinguished between Mexico and the United States, American printers inadvertently left a corpus of badly printed books that contradict the central premise of that argument.

U.S. print culture in the era of the Mexican War demonstrates how the American republic’s first foreign war brought together nationalism and the print market in ways that anticipated the role of modern mass media in shaping public responses to warfare. Both the content of American book publishing (soldier narratives, military histories) and the media formats themselves (the technologies of text production and visual culture) worked in the service of propagandizing a war that, as Amy Greenberg reminds us, did in fact have a vocal minority of critics in the public sphere. That these works of public “history” were, more often than not, either highly selective in their presentation of facts or downright fictitious shouldn’t lead us to overlook the political implications of Mexican War literature. Quite the contrary. As demonstrated here, the Mexican War is an important flashpoint in tracing a longer history of the tactics of a mass press that transformed its source material into fodder for popular reading. The war inspired racist stereotypes about a nation (Mexico) and an ethnic category (Latinos) that remain crucial elements of American hemispheric and transnational cultural politics.

The classic treatment of the U.S.-Mexican War in popular culture is Robert Johannsen’s To the Halls of the Montezeumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination (New York, 1985). Shelley Streeby’s American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture (Berkeley, 2002) offers the best analysis of Mexican War fiction. For a recent history emphasizing popular opposition to the war within the United States, see Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York, 2012).

Robert Armstrong’s Feb. 13, 1848, letter to his sister is from the Mexican War Collection, University of Texas, Arlington, Special Collections. C.B. Ogburn’s December 1847 letter from Saltillo is held by the New-York Historical Society. John Wolcott Phelps’s diaries from the Mexican War are at the New York Public Library, Manuscript and Archives Division. In A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War (Chapel Hill, 2002), Paul Foos recovers the experience of American soldiers and notes their reticence in writing about military violence. Peter Guardino explores a fascinating comparative study of Mexican and U.S. soldiers in “Gender, Soldiering, and Citizenship in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848,” American Historical Review 119.1 (2014): 23-46.

On the varieties of nineteenth-century American autobiography, see Ann Fabian, The Unvarnished Truth: Personal Narratives in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley, 2000). The full text of the published editions of Camp Life of a Volunteer (1847) and H. Judge Moore’s Scott’s Campaign in Mexico (1849) are available via the Internet Archive. The manuscript diaries of Benjamin Franklin Scribner and H. Judge Moore are available at the University of Texas, Arlington, and Yale University’s Beinecke Library, respectively. Scott E. Casper discusses Hawthorne’s biography of Franklin Pierce in Constructing American Lives: Biography & Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, 1999). Franklin Pierce’s Mexican War diary (1847) is held at the Huntington Library and is microfilmed as part of the Franklin Pierce Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

For a helpful summary of nineteenth-century printing presses I consulted Elizabeth M. Harris, Personal Impressions: The Small Printing Press in Nineteenth-Century America (2004).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.1 (Fall, 2016).

John Garcia is currently lecturer in humanities at Boston University’s College of General Studies and a visiting instructor in the English Department of Clark University. He was the 2015-16 Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in American Literature at the American Antiquarian Society, and has held Mellon fellowships at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies and the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. His research on book distribution and the print culture of the U.S.-Mexican War is part of a larger project on bookselling in early America.

On April Fools Day in 1857, an article just two sentences long appeared on the front page of The New York Times, announcing the U.S. government’s plan to purchase Mexico’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec for $15 million. It was no joke, but why did the U.S. government want to buy (at a bargain-basement price) the Mexican isthmus? The word “Tehuantepec” hasn’t appeared on the front page of the New York Times since 1938. These days, most people in the United States have never heard of the region. But in the 1850s, it was as familiar as Puerto Rico is today.

The New York Times began publication in 1851, less than three years after the U.S. annexation of northern Mexico—what would become California, Oregon, Washington, and several other U.S. states—after the U.S.-Mexico War. During its first two years in publication, the Times ran hundreds of articles about the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. A news column titled “Isthmus of Tehuantepec” appeared regularly in the newspaper’s front section.

Mexico’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec is a 120-mile-wide slice of land that stretches east-west, connecting the Yucatan Peninsula to the rest of Mexico. An 1865 U.S. atlas shows the isthmus as a separate state, not part of the states of Veracruz and Oaxaca, as it is today. In the left corner of that map, there is also a detailed map of the isthmus—the only part of the country the cartographers chose to show in detail for a U.S. audience. Why so much attention from U.S. cartographers, politicians, and journalists devoted to a tiny sliver of Mexican land?

To understand that flurry of nineteenth-century interest in a region now little known to us, we must to turn our attention to the narrow dirt road that cut across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec a century and a half ago. In 1853, four years before that two-sentence New York Times cover article announced U.S. government designs on the isthmus, local residents there seceded from the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz, announcing a new Mexican state, with its capital in the city of Tehuantepec. In 1855, a group of New York investors completed a railroad across the Panamanian isthmus, at that time still part of Colombia. And finally, just four months before the April Fools Day story, a U.S. company completed the “Tehuantepec Turnpike”—an earthen path wide enough for a stagecoach—running from the Coatzacoalcos River that drained into the Gulf of Mexico and La Ventosa Bay, on the southern, Pacific coast of the isthmus.

The Tehuantepec Turnpike opened a decade after the U.S. annexation of northern Mexico. Even more important, it came a decade before the completion of the first U.S. transcontinental railroad. The U.S. government, and its corporations, urgently needed a faster route between the country’s east and west coasts. In an era when transport was primarily via water, U.S. leaders looked south. In the years that followed the annexation, plans for the next North American grab (or purchase) of Mexican lands became a regular topic of debate on the pages of U.S. newspapers. Should the United States annex Baja California? The states of Sinaloa and Sonora along the Sea of Cortez? Or Tehuantepec? The Mexican isthmus offered the United States a link between the east and west coasts of our suddenly vast country.

At that time, there were only two routes for mail and news between New York and San Francisco. One was the Pony Express, a network of riders who made the dangerous two-week trip across snowy mountain passes and dry plains. The other route took nearly as long, via ship from the East Coast, then railroad across the Panamanian isthmus, then another ship to the West Coast. Tehuantepec offered the third option. In November 1858 the first bundles of “California mails” arrived in the Gulf port of New Orleans, having traveled from San Francisco via the Tehuantepec isthmus. The packages arrived in New York a full week earlier than those shipped via Panama. New York Times articles about the new western territories began by noting, “The mails have arrived from Tehuantepec.”

A Times article published in February 1858 declared, “[L]et a stable government be established and the tide of American progress will set resistlessly toward the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.” There was regular steamer service between the U.S. Gulf coast and the Mexican port city Coatzacoalcos. The next logical step was to transform the dirt-road turnpike into a state-of-the-art planked roadway. Huge crates of wood for building frame houses arrived from Florida and construction workers arrived from New York with four months’ provisions.

Those U.S. workers showing up to transform the built environment of the Mexican isthmus continued a trend started by those who had built the Tehuantepec Turnpike. The word turnpike, meaning toll road, comes from the Middle English words turne pike meaning “spiked barrier.” The name probably seemed particularly appropriate to the istmeños—the local residents—when gringos showed up with steamer boats, scythes, and rifles to cut a stagecoach road through field and forest.

The hundreds of Times articles published about the Mexican isthmus between 1851 and 1858 focused on its role in U.S. hemispheric interests, and on the natural resources available there for exploitation. In the late 1850s, with a small but significant number of North Americans living in the region, daily events on the isthmus became worthy of detailed description. Here is one example from the northern isthmus city of Minatitlán, in 1858:

The river at this time is quite high, though as yet we have had no flood. Should we not have one, many of those engaged in the mahogany cutting will be unable to get out their year’s work, and will thus be greatly injured pecuniarily….

The town is improving. Carpenters command good wages; that is, from $2.50 to $3.50 per day. We have but very few here sick, and it may be said that the health of the town is very good. Most people upon their arrival have a slight attack of the calentura, but with care, and a low diet, it soon passes off. It is generally brought on by mixing fruit and liquor, and strangers can rarely be induced to believe the mixture injurious until they have felt the effects of indulgence.

The opening of the Tehuantepec Turnpike made both mahogany-cutting and colonization possible. A few years after the turnpike was completed, a French visitor to the isthmus noted that the region’s forest was “overly frequented by the North Americans, and had already lost a large part of its virgin beauty.”

Upbeat reports of the expanding U.S. presence in isthmus towns were one of three types of articles that appeared in the Times during this period. The other two often contradicted each other. Opinion leaders in Washington, D.C., and New York promoted the region’s positive attributes, including vast natural resources and purportedly good weather. An 1858 New York Times editorial noted: “The route passes through a healthy and delightful region, and when opened will be a favorite with the traveling and trading public.” On-the-ground reports from North American travelers rendered a more complicated reality. Just two months before that editorial appeared, a traveler from San Francisco, John Hackett, complained in a long letter to the editor about “the rays of burning sun.” Anyone who has traveled at midday on horseback in the isthmus region—as nineteenth-century travelers did—knows that Hackett came closer to the truth.

On February 19, 1858, John Hackett boarded a southbound ship called Golden Age in San Francisco. Six days later, in Mexico’s Pacific port of Acapulco, he and fifteen others disembarked, then boarded the steamer Oregon, bound for the Mexican isthmus, which lay further south. There should have been sixteen traveling with him, Hackett reported, but one of the passengers, “while under mental aberration, superinduced by whiskey,” had climbed off the Golden Age and drowned.

Oregon reached La Ventosa Bay, at night. Around daybreak the following morning, March 1, two metal boats arrived shipside to take both travelers and baggage to shore. Huge waves pummeled the Oregon, threatening to smash the small boats against its hull. After the passengers flung their trunks and themselves from ship to boat, seven istmeños rowed them to shore. Both the harshness of the local environment and the skill of the local boatmen in overcoming it impressed Hackett. Twenty yards from shore, the boats bottomed out. The indigenous longshoremen jumped into the water, hauled the boats onto their shoulders, and carried the travelers to dry sand.

The travelers then entered the customs office, a thatched-roof hut, before slogging three-quarters of a mile through the sand to board a stagecoach for the city of Tehuantepec. Three hours later they had traversed the fifteen miles “of tolerably smooth road” to arrive in the city of Tehuantepec. The easy ride ended there. After that, Hackett reported, the ride on the Tehuantepec Turnpike was “jolting to such an extent as to pound one almost to the consistency of a jelly.” When the path was too rough for the stagecoach, the passengers rode horseback.

About the time they passed what is now Matías Romero, one man “got off his animal, staggered and fell.” They managed to carry him to a nearby camp, but there was no one to offer medical help. He died about fifteen minutes later. He carried $1,300 worth of gold—a goldrusher returning from the West Coast with the loot he panned from California’s rivers. The gold that was once Mexican returned to Mexican soil.

The travelers finally reached the end of the stagecoach line, at the town of Suchil—the dateline for many New York Times articles about the isthmus. Hackett noted dryly that the long-anticipated Suchil was “an imposing city of three staked wig-wams and one wooden house.” The steamer to New Orleans was supposed to meet them there, but since it was the dry season, the Coatzacoalcos River ran too low to be navigable. Hackett bragged that he and his traveling partners rowed themselves down the river in a dugout mahogany canoe for a day and a half, with nothing but river water to sustain them.

When he finally reached New Orleans on March 9, Hackett wrote to the editors of The New York Times immediately. His long account ended, “I have detailed without the slightest exaggeration my actual experience across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and regret that these embarrassments to the perfect success of the route exist.” He concluded that the geography of the region “must ever be a stumbling block in the way to the perfect success of the [trans-isthmus] route.”

In spite of Hackett’s pessimistic testimonial, news articles datelined Minatitlán or Coatzacoalcos reflected a bustling Isthmus of Tehuantepec that resembled any North American Wild West outpost. September 1858: “We stand in need here of a newspaper, and a cabinet-makers’ shop.” August 1859: “Quite a number of wealthy Mexicans from the City of Mexico are now on the isthmus locating lands and taking up territory, which they feel satisfied must soon come under the United States.”

In early New York Times articles about North American expansion on the isthmus, local residents were rarely mentioned. But as the carpetbaggers began to face hard times in the late 1850s, news articles focusing on native istmeños began to appear for the first time. The Times correspondent in Minatitlán noted in 1859:

The new church is to be dedicated to-morrow, and I have never heard so much noise, and of such variety, on any similar occasion. First, there is the constant firing of an old gun near the church, then the ringing of a half-dozen bells which have been gathered from wrecked vessels…The natives, large and small, male and female—but particularly the latter, who are the most pious—have been busy for several days in toiling earth from a neighboring hillside, in aprons, bags, and turtle shells, and depositing it near the church. The people here are very cleanly in their habit, and are perfectly honest. Mechanics drop their tools on the spot where they work, and nothing is ever taken. No one thinks of locking his doors here as a security against thieves.

Even as New York Times writers and editors seemed to perceive the isthmus in the most utilitarian terms—a short path between the oceans—the place still held mystery. Their reports exoticized it, suffused it with an other-worldly quality. As one article put it, the place had a “lifeless and dreamy appearance.” The journalist continued, “The rainy season has commenced, and the few showers we have already had have covered the surrounding mountains with verdure. I returned from Ventosa this morning and was delighted with the variety and fragrance of the flowers which literally perfumed the lonely forest-road…” (The writer conveniently leaves out the mosquitoes, also brought by the rains, which in turn brought yellow fever.)

The optimism about the region’s potential for the U.S. government, then focused on the realization of Manifest Destiny, was short-lived. In September 1859, newspaper headlines hinted at boom towns busting: “Isthmus of Tehuantepec: Rainy and Sickly Season—Desperation and Hard Swearing Among The Employees—Robbery of the California Mail—New Rumors, &c” With temperatures topping 120 degrees and foreigners sweating out severe fevers, looters attacked the incoming ships from the United States, robbing passengers and pilfering the mail. The Tehuantepec Turnpike collapsed into economic ruin. Gringos who had traveled to the isthmus looking for jobs and opportunity languished, unable to afford return passage home.

Tensions rose between the istmeños and gringos. By February 1860, U.S. Marines were stationed at the isthmus city of Minatitlán, supposedly to protect North Americans living there from Mexican soldiers. Istmeños became outraged at the presence of U.S. troops in their towns. Mexican government officials demanded an explanation from the U.S. consul in Minatitlán: what was the U.S. military doing on the isthmus? According to a New Orleans journalist living in Minatitlán, the consul insisted, “[T]he United States of America had the right to send their men-of-war to any part of the globe where they had fellow countrymen to protect.” Minatitlán’s North American enclave began to fear “the seizure of all American property and the assassination of American citizens.” The tension led to a Mexican-only meeting, at which “the discussion was long, heated and acrimonious. Finally, after four hours’ deliberation, it was decided that the Americans, in the port of Minatitlán, be treated coldly but politely, until sufficient force be obtained to drive them out.” Even the New Orleans journalist acknowledged, if indirectly, that the North Americans lived on isthmus land without the blessing of the istmeños.

As the situation became more difficult for North Americans on the isthmus, the political situation shifted back in the United States. The conflict between the U.S. North and South grew, exploding into the Civil War in 1861. The Union government feared the growing economic power of the Confederate South. Suddenly, cargo ships moving busily between Coatzacoalcos on the isthmus and the Southern ports of Mobile and New Orleans were seen as a threat bolstering the Confederacy’s economy.

From those southern ports, the Gulf port of Coatzacoalcos is less than half as far as the Panamanian isthmus. However, Panama lies so far east that it’s slightly closer to New York than Coatzacoalcos is. As far as northerners were concerned, the Tehuantepec isthmus offered no geographic advantage over the Panamanian isthmus. With the U.S. South economically and politically weakened by the Civil War, U.S. government and corporate interest in Tehuantepec faded.

However, once the Civil War ended, the political winds shifted back; interest in the Mexican isthmus rose again. An economically prosperous U.S. South was no longer perceived as dangerous, but necessary. In 1867, just two years after the war’s end, a U.S. company based in New Orleans signed an agreement with the Mexican government to build a railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. A U.S. Navy expedition, led by Robert Wilson Shufeldt, was sent to survey the region for a new transcontinental transit corridor. The group, which included hydrologists, astronomers, engineers, naturalists, photographers, and meteorologists, arrived in Minatitlán on November 11, 1870. The expedition’s long report to the U.S. government included everything from the region’s hydrology, to lists of native plants, to a short glossary from the local languages of Zapotec and Zoque. The report was enormously detailed, cataloguing the type of soil under every isthmus village they visited, the type of rock on every hill they climbed, the location and appearance of each tree species that gave them shade.

The report is remarkable in both its precision and its single-mindedness. The lists of animals, minerals, soils, plant species, and local vocabularies have a relentless focus: assessing the usefulness of the natural resources for commercial exploitation. Shufeldt’s findings were encouraging, from the perspective of North American industrialists. Nonetheless, they received scant mention in The New York Times. A single sentence appeared on the newspaper’s front page in April 1871, datelined Mexico City, announcing “the discovery of a practicable route” across the isthmus.

The dream of a U.S.-controlled transit corridor was foiled again in 1871, this time by events in Mexico. Political unrest exploded following the close presidential race between Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz. The North Americans still living in the isthmus region were caught up in the violence. When posters appeared on their front doors threatening their lives, they abandoned their cotton plantations and mahogany sawmills. Their letters tell of their panicked departure: “We must abandon the Isthmus to God and the Mexicans.” “The foreigners are flying for their lives.”

English capitalists saw opportunity in the North Americans’ flight. With Canada’s growing autonomy, England sought another path across the Americas to India. The U.S. looked on grudgingly, considering it “England in our waters.” The U.S. government worried about the threat to North American supremacy in the region, whining that Mexico was only doing twice as much trade with the United States as it was with England. An 1885 article, reprinted from The Mexican Financier, ascribed ulterior motives to England’s interest in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec: “It may be that English diplomacy would like to build up on the southern border of the United States a strong nation, not openly hostile to American influence on this continent, but yet quietly exerting a counteracting force to American supremacy.”

In spite of gringo fears, a joint British-North American company finally completed construction of the first Mexican trans-isthmus railroad in 1894. On September 11 of that year, the inaugural train made the trip from the Gulf port of Coatzacoalcos to the Pacific port of Salina Cruz in ten hours and twenty minutes. TheTimes reported, “The Mexican Government is determined to make the National Tehuantepec Railroad a great international traffic route. In order to bring about the desired result extensive improvements will be made to the harbors of Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz …” Still, after investing somewhere between $25 million and $50 million, the isthmus had only, as the Times put it, “utterly worthless track.” By the turn of the twentieth century, the railroad offered nothing to international commerce. Though still viable for local transit, its tracks were unable to support the weight of loaded boxcars, while the ports at either end were far too small for seagoing ships.

Meanwhile, U.S. government attention had shifted south, to digging a canal across newly independent Panama, where both land and government seemed more compliant.

An earlier version of this essay appears (in Spanish) in the book Región del Istmo de Tehuantepec: Interacciones sociales y flujos comercios, published in 2011 by the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (Center for Advanced Studies and Research in Social Anthropology) in Oaxaca, Mexico. Portions of it also appear in Wendy Call’s new book No Word for Welcome: The Mexican Village Faces the Global Economy (Lincoln, Neb., 2011).

In addition to the digital archive of The New York Times, available at many libraries, two articles provide key historical detail about Mexico’s trans-isthmus railroad: Paul Garner’s “The Politics of National Development in Late Porfirian Mexico: The Reconstruction of the Tehuantepec National Railway 1896-1907,” from the Bulletin of Latin American Research 14:3 (1995) and Francie Chassen-López‘s “El Ferrocarril Nacional de Tehuantepec,” from Acervos 10 (Oct.-Dec. 1998). Dr. Chassen-López’s book, From Liberal to Revolutionary Oaxaca: The View from the South, Mexico 1867-1911 (University Park, Penn., 2004), offers a deeper sense of the economy and society of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the late nineteenth century.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.4 (July, 2011).

Thirty years ago, Robert W. Johannsen published To The Halls of the Montezumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination, inspiring historians to explore the impact that the conflict had on American society. Since then a number of books have examined how the U.S.-Mexican War influenced the domestic politics and culture of the United States. Adding to this growing body of work is John C. Pinheiro’s Missionaries of Republicanism: A Religious History of the Mexican-American War. This latest volume in Oxford’s much-touted “Religion in America” series draws from an impressive collection of antebellum sermons, pamphlets, broadsides, letters, and memoirs to bring to light the religious context of the United States’ 1846 invasion of its southern neighbor. Specifically, Pinheiro argues that the religious history of the U.S.-Mexican War shows “how anti-Catholicism emerged as integral to nineteenth-century American identity as a white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant republic” (1). Indeed, animus toward Mexico’s state religion played a role in many aspects of the conflict, from the recruitment of soldiers to the drafting of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Pinheiro introduces his study by highlighting the growing anti-papist fervor of the Second Great Awakening. Although a distrust of Catholicism existed before the framing of the nation, increasing immigration from Ireland and a growing fear of Vatican plots in northern Mexico during the 1830s converted a religious issue to a political one. In 1834, nativist Protestants burned the Ursuline Convent and School at Charlestown, Massachusetts, an event the author considers seminal to galvanizing anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment in the nation. Not coincidentally, this occurred as Yankee pioneers began to covet the Mexican provinces of Texas, Nuevo México, and Alta California. Pinheiro documents how this decade-long process influenced both United States’ society and politics.

As Americans looked westward for new territory, many viewed mixed-raced Mexicans and their Roman Catholic religion as inferior and incompatible with the Anglo-Saxon Protestant republicanism that was fated to sweep the continent. Firebrand ministers such as Lyman Beecher synthesized the ideas of white supremacy, anti-Catholicism, and Manifest Destiny into books, sermons, and pamphlets which shaped public perceptions of Mexico. Anti-Catholicism began as a domestic phenomenon, but its philosophies infiltrated the nation’s foreign policy following the presidential election of 1844. This contest was essentially a referendum on Manifest Destiny, with expansionist Democrats scoring a narrow victory, putting the United States on the path of war with Mexico.

After setting the stage for conflict, the book focuses on the ways in which anti-Catholic rhetoric was used to recruit volunteers to fight in Mexico. This was no easy task as immigrants born in Ireland and southern Germany composed a sizable minority of the standing army in 1846. President James K. Polk and his commanders Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott also understood the danger of Mexico perceiving their campaigns as a religious war. To counter the appearance of a sectarian crusade, the president ordered Catholic chaplains to accompany the military into Mexico.

Later chapters examine how anti-Catholicism affected the waging of the war, from the goals of the political elite to the behavior of enlisted men and volunteers. As conflict came to the nation, Whigs, Democrats, nativists, and abolitionists all engaged with anti-Catholicism, often at their own peril. Democrats, in particular, had to balance their desire for national expansion with their growing Catholic electoral base. This continued to be a difficult feat as American troops pushed farther into Mexican territory in 1847. Pinheiro notes that “American politicians recognized that only through some combination of anti-Catholic sentiment, racism, and republican principles could they maintain a nationally coherent stand on the war” (107). He finishes his study with an analysis of how such sentiment shaped congressional debates over the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and how this bigotry gave rise to the short-lived but influential Know Nothing Party of the 1850s.

Pinheiro’s research is exhaustive and his writing clear. As the director of the Catholic Studies Program at Aquinas College and a noted scholar of the early American republic, he is firmly in his element. Among his most interesting discoveries is the relationship between race and religion during the 1840s. While there has been significant work done in the role of race in the United States’ decision to invade and annex northern Mexico, Pinheiro adds to this by demonstrating the ways in which many Americans conflated race and religion in forming their opinions of Mexico. Drawing from an interesting diversity of sources, the author highlights the anti-Catholic rhetoric that droned in the background of the national dialogue about Manifest Destiny.

Pinheiro focuses on many instances of religious bigotry, but he is careful not to paint the nation with too broad a brush. While giving numerous examples of the bigoted views and actions of individual soldiers, for example, he does not ascribe anti-Catholic motivation to all servicemen. In fact, he cites several instances of Catholic officers and enlisted men fighting in Mexico with as much vigor as their Protestant counterparts. This is in keeping with Tyler V. Johnson’s complementary Devotion to the Adopted Country: U.S. Immigrant Volunteers in the Mexican War, which showed how many Catholic soldiers saw the war as a way to prove their patriotism and allegiance to the United States.

Although its subtitle hints at a more comprehensive work, Missionaries of Republicanism: A Religious History of the Mexican-American War is largely focused on pervasive anti-Catholicism in the United States. There are enticing mentions of Catholic counterstrategies, denominational schisms over slavery, violence against Mormons, and Catholic reactions in Mexico, but this book is primarily concerned with evangelical Protestants in the lead-up to and execution of war. This is not to say that Pinheiro’s study is in any way deficient. He proves his thesis by clearly linking the development of American identity during the U.S.-Mexican War to the era’s marked opposition to the Catholic Church. Even so, promise remains for other perspectives in the complex religious history of this oft-overlooked war, and Pinheiro is to be commended for opening the door to this future research.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3 (Spring, 2015).

Michael Scott Van Wagenen is an associate professor and public history coordinator at Georgia Southern University. He is the author of The Texas Republic and the Mormon Kingdom of God (2002) and Remembering the Forgotten War: The Enduring Legacies of the U.S.-Mexican War (2012).

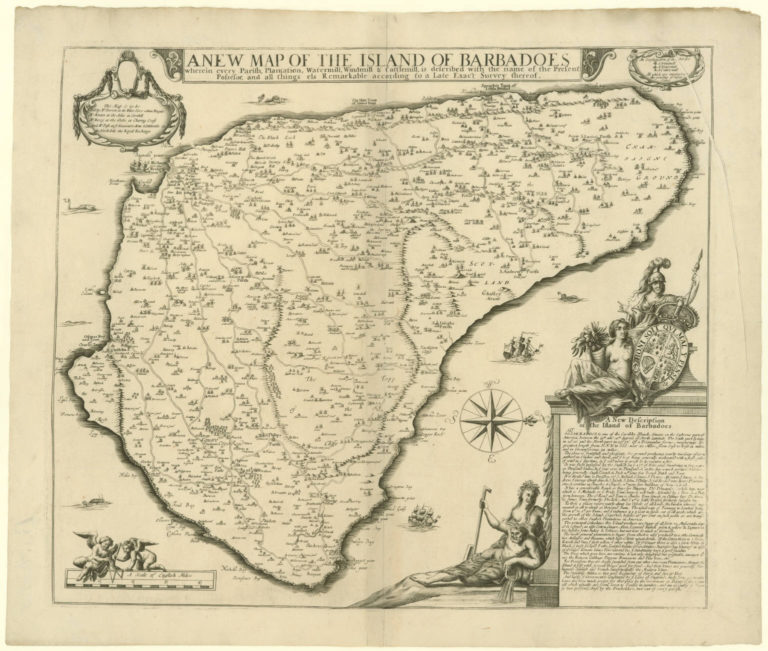

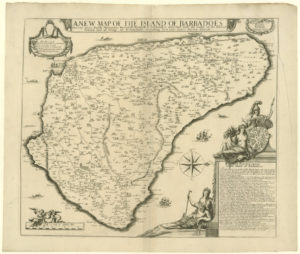

Creative Commons license

In the summer of 1680, the governor of Barbados, Jonathan Atkins, sent a chart of this “Caribby” island “Situate on the Easterne part of America” to the Council of Trade and Plantations in London. The copy he submitted is likely the one pictured here (Fig. 1), now in the Map Collection of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. Entitled A New Map of the Island of Barbadoes wherein every Parish, Plantation, Watermill, Windmill & Cattlemill, is described with the name of the Present Possesor, and all things els Remarkable according to a Late Exact Survey thereof, the impressive cartographic image was drawn from a survey undertaken by the Bridgetown-based Quaker Richard Forde. Measuring roughly a half-meter squared, it shows the island fully inhabited and barely a patch uncultivated; the entire territory, criss-crossed by roads, is studded with English names and symbols marking plantation houses and mills. Even the title’s repetition of “mill” seems designed to propel our sense of the colony’s continuous, contiguous industry—all these mills being, as the key in the top-right corner explains, “imployd in the grinding of Sugar Canes.” By the 1660s, Barbados had become probably the most densely populated and intensively cultivated agricultural area in the English-speaking world, deeply interconnected with England’s other colonies in America and far beyond. In the early 1680s the free white population is estimated to have reached around 20,000; the enslaved black population, whose brutal forced labor supplied and worked the mills, outnumbered the whites by more than two to one. The violence, and indeed even the mere fact of slavery, is silenced by the map.

Looking at this peaceful, productive view alone, you would likewise never imagine that five years earlier, in August 1675, Barbados was hit by a devastating hurricane that reduced the machinery of the booming sugar industry to smithereens. “Never was seen such prodigious ruin in three hours,” wrote Governor Atkins in a letter to officials in London. A thousand houses, three churches and most of the mills on the west side of the island were destroyed, and hundreds of people were killed, “whole families being buried in the ruins of their houses.” The disaster went down in colonial history as one of the most dreadful events that ever happened to the island, which “changed much the face of the country.” The effects were exacerbated by the scale and density of the settlement by 1675, and by a hurricane the previous year that “whirled us like a top about all points of the compass” and did great damage. With each hurricane, the lack of shelter resulting from extensive deforestation left people, buildings and crops more vulnerable.

In transforming the physical landscape, the hurricanes also disturbed the stratified social landscape. Refusing to discriminate between free, indentured and enslaved, they tore down the built spaces that regulated and reinforced these differences. The literal and figurative levelling effect raised the idea, very dangerous to the interests of the colonial elite, that everyone was equal after all, and opened up space for resistance. An anonymous pamphlet published in 1676, Great Newes from the Barbadoes, Or, A True and Faithful Account of the Grand Conspiracy of the Negroes against the English (see title page in Fig. 2), exposes how the fear within the colonial elite elicited a murderous response to the threat of a slave rebellion: the title page highlights the number (at least 42) “of those that were burned alive, Beheaded, and otherwise Executed for their Horrid Crimes.” It is in the context of this brutal oppression, and the propaganda of the pamphlet—which concludes with the line that Barbados is “the finest and worthiest Island in the World”—that we should consider the map.

The picture of calamity, chaos and confusion conjured by textual descriptions of the successive hurricanes and their aftermaths is ostensibly countered by the map’s calm visual order (the note on climate in the “Description” mentions only the “fresh gales of wind” that relieve the heat of a typical day). Yet uncertainty over the print’s production, publication and reliability reflects the rupture, exacerbated by the distance of space and time between colony and metropole.

Forde appears to have drawn up the map (in draft form at least) by January 1675 and sometime afterwards sent it to England to be “perfected” and published. Yet there is evidence to suggest that, with his draft in effect torn up by the hurricane in August 1675, he was attempting to revise it according to new conditions in the summer of 1676 and perhaps even later. Meanwhile, the Lords of Trade were growing impatient at the “want of maps” they believed was hindering their administration of the colonies, and ordered all overseas governors to “send home maps of their plantations.” Atkins (and he was not alone) was slow to deliver. In 1679, four years after the initial request, he received a letter insisting that he despatch “what their Lordships have already demanded without effect, viz. description and map of the country which he promised to send in 1675.” When the map finally arrived in Whitehall in 1680, Atkins was not at all confident it served the purpose: “I have at last procured a chart of the Island, but I cannot commend it much,” he wrote; “that it is true in all particulars I cannot assume.” The disturbances and transformations incurred by the hurricane must in part account for those doubts—in addition to the Quaker surveyor’s deliberate omission (for religious reasons) of the word “church” and almost any sign of fortifications, the coverage and condition of which for the purposes of both internal and external defense were a prime concern of officials in London.

We do not know exactly what imperial officials thought of the map, but without close inspection they may have been pleasantly surprised and reassured by the handsome image. The print shown here was certainly added to the Office of Trade’s growing map library and today remains among a sampling of that once-extensive collection known as the Blathwayt Atlas (after the Office of Trade’s secretary William Blathwayt, who oversaw their acquisition in the 1670s and 1680s). The inclusion of Barbados, alongside maps charting an array of colonial and commercial settlements from Massachusetts Bay to Bermuda and Bombay, confirms the island’s importance within England’s expanding territorial interests through the seventeenth century, not just in the Atlantic region but around the world. Thanks to recent digitization by the John Carter Brown Library, it is now possible to view the Blathwayt Atlas maps online and to study individual items in minute detail—to see them both in context and close-up.

Scholars have stressed the importance of Forde’s work as the “first systematic” and “first economic” map of the island, but from such a perspective (like that of Governor Atkins) the details may disappoint, or indeed obscure. A prime purpose of the printed work, through its powerful combination of image and text, was to promote the colonial project and persuasively smooth over its challenges and contingencies, and the coercion at its core. That Forde’s map did so successfully for audiences in England is suggested by its continued use in different editions over a period of more than thirty years. With its simultaneous projection of progress and indeterminate history amid the hurricanes, the New Map of the Island of Barbadoes leaves us with a complex view of a colony—and empire—in the process of construction and reconstruction.

Further Reading:

The only full study to consider the significance of the maps as a collection is Jeannette D. Black’s The Blathwayt Atlas, 2 vols (Providence, RI, 1970-75). On Forde’s map (including the spelling of his surname, often given simply as Ford), see 180-85. See also P. F. Campbell, Some Early Barbadian History (St Michael, Barbados, 1993), 191-96. For a social and economic perspective that discusses the map in relation to a contemporary census, see Richard Dunn, Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713 (Chapel Hill, NC, 1972; repr. 2000), 84-116 (esp. 96-100), an expanded version of Dunn’s “Barbados Census of 1680,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., 26 (1969): 3-30. For a recent digital humanities approach, see Peter Koby, “The Modern Utility of Ford’s Colonial Map of Barbados, 1674,” Journal of Map and Geography Libraries 11, no. 1 (2015): 60-79. For introductions to demography, society and identity in Barbados within an early modern American context, see Dunn’s works above and Jack P. Greene, “Changing Identity in the British West Indies in the Early Modern Era: Barbados as a Case Study,” in Imperatives, Behaviors, and Identities: Essays in Early American Cultural History (Charlottesville, VA, 1992), 13-67. The correspondence between Governor Atkins and the Lords of Trade is recorded in the Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, America and West Indies.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.3 (Spring, 2017).

Dr. Emily Mann is a postdoctoral Research Associate with the Centre for the Political Economies of International Commerce (PEIC) at the University of Kent and, from September 2017, Early Career Lecturer in Early Modern Art at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. She is working on an edited volume exploring the Blathwayt Atlas maps. emily.mann@courtauld.ac.uk

Historians slip easily into categorical thinking. We assign a group or a trend to a category, such as “pirate” or “puritan,” and then all too often we let that well-worn category do the work of analysis. Designating an individual a pirate bestows motives and perspectives, creating a shortcut to deeper understanding. That ubiquitous (and in American historiography nearly meaningless) category of “puritan” covers a multitude of religious inclinations and explains numerous aspects of human existence, from childrearing to politics. Categories allow us to gloss over context and, more importantly, over gaps in evidence. When we have few sources, assigning a category automatically fills in silences and suggests explanations consistent with the particular group or movement. In this era of click-bait headlines and little time to settle in with a complicated and nuanced book (not to mention pressures to publish), categories offer a quick way to make sense of complex phenomena.

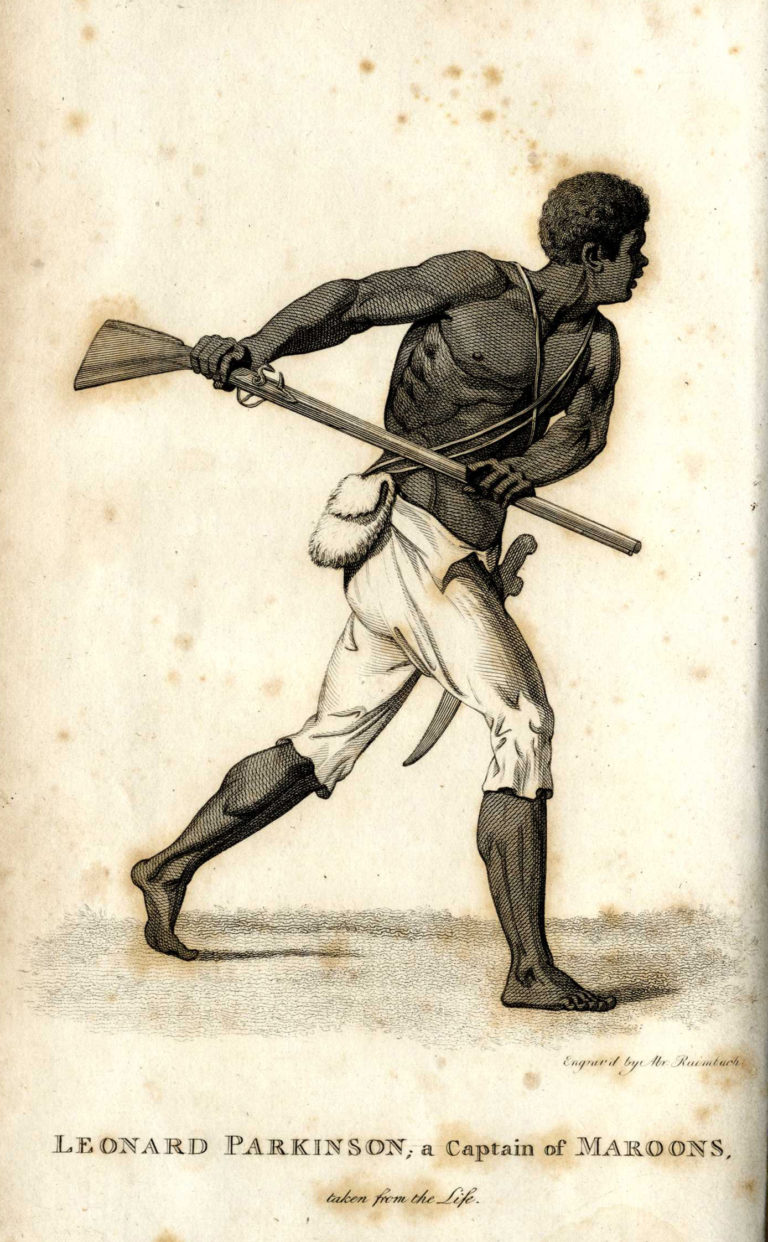

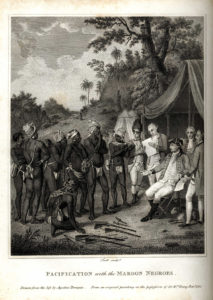

Maroonage represents a case in point: a widespread but only sporadically documentable historical trend, the category of maroon invokes a host of historical specificities. Maroons created independent enclaves of formerly enslaved people and eventually their children, away from and beyond the control of their masters. The Spanish who first confronted and named such a population labeled these communities of escaped slaves “cimarróns,” a term for domesticated cattle that had escaped to live feral in the woods or mountains. The English employed a variation of the word later when they encountered such communities in the Americas. Maroonage arose in locations where geography cooperated, flourishing in topography that granted runaways places not only to hide but to carve out permanent habitations away from their former masters. They emerged on larger islands or the South American mainland where inaccessible retreats sheltered organized enclaves of former slaves. They sustained themselves by growing their own food crops, culling semi-feral livestock, and stealing from the plantations where they had once been held in bondage. They offered haven to later runaways, thereby augmenting their populations; on occasion in Jamaica and elsewhere, they agreed with colonial authorities to return fleeing slaves in exchange for being left alone. Maroonage provided numerous Africans and their descendants an opportunity to live independent of slave regimes. Before the dramatic success of the Haitian Revolution, maroons enjoyed the best hope of African autonomy and self-determination in the Americas. Historians today find the category maroon infinitely appealing, a reversal of the discomfort and confusion with which European imperialists viewed them at the time.

The seductiveness of this category and of categorical thinking generally has shaped the standard narrative of the origins of the Jamaica maroons, one of the best known cases of maroonage in the Caribbean. Their oft-repeated story dates their origins from the English invasion of the island in 1655. In the prevailing account, the invasion granted the island’s slaves an opportunity to flee their Spanish masters and establish the first independent maroon communities in the Jamaican mountains. In doing so, they successfully removed themselves from the slave system, forming autonomous enclaves free of both colonial and imperial authority. The Jamaica maroons persisted for over a century and successfully fought off imperial forces on numerous occasions. Finally in 1796, victorious British authorities demanded that they leave the island en masse. Despite the eighteenth-century order to leave, maroons persist in Jamaica to this day, and many others retained their identity in diasporic movements to Nova Scotia and later West Africa.

This narrative of Jamaica maroonage arising in the aftermath of the English invasion, while highly serviceable, obscures the origins of the autonomous African communities that organized in the Jamaican hinterland. The first independent enclaves were not runaway slaves but rather refugees. They came together in the mountains during an ongoing guerrilla war that pitted the island’s residents under Spanish rule against the newly arrived English invaders. Not classic runaway maroons, they constituted a community of refugees of mixed status (both enslaved and free) who together chose a separate existence in a context of warfare, conquest, and potential exile. Among the assortment of Jamaicans who fled to the interior, those who chose to reside there permanently and peaceably withdrew from the war between Spanish and English forces on the island. They opted out of moving to Cuba, where they would have taken up a social status (whether slave or free) in accordance with that which they had held in Jamaica before the invaders disturbed them. Instead, they chose to fashion a new life of subsistence and autonomy away from both English and Spanish colonists. Their decision was collective rather than individual, and the options they had differed from those available to runaway slaves. By consigning their experience to the category of maroon, we assume we know their identity (former slaves) and goals (autonomous living separate from their masters) even in the absence of definitive evidence.

The men, women and children who erected villages in the isolated reaches of Jamaica did so within a context of warfare and displacement. When the English invaded Jamaica, virtually all the residents of the island fled. Initially everyone ran from the main town of Santiago de la Vega, taking their valuables with them. They had been through this drill before: bands of raiders arrived, at irregular intervals, intruding briefly in search of wealth and food and water to resupply their ships. Later, when the population knew that the invaders intended the permanent capture of the island, almost everyone withdrew farther into the mountains rather than accept the terms of the treaty they were offered.

An invasion changed the situation dramatically, forcing the islanders to consider a new future very different from the lives they had lived on Jamaica. The English terms granted European colonists exile to an unnamed Spanish American territory, with transportation provided compliments of the English navy. A handful took that option, becoming wartime refugees, dumped on another population and dependent on the aid it offered. The English hoped that non-Spanish residents would throw their lot in with the invaders. The conquering army also ordered “that all the slaves, negroes and others be ordered by their masters to appear [at a designated meeting place and time] . . . to hear and understand favours and acts of grace that will be told them concerning their freedom.” Expecting these subaltern populations to greet the English as liberators, the army commanders declined to spell out the details of this offer until the meeting. But the African-descended residents chose not to take their chances on the English. This refusal stunned the English, who were aghast when not one slave appeared at the meeting place. With the small resident population—a mix of Spanish, Indian and African—scattered in the inaccessible interior and the English army encamped around Santiago de la Vega (today’s Spanish Town), the scene was set for a five-year-long guerrilla war. The resistance would be fought under the command of a Spaniard, Cristoval Ysassi, whom Philip IV eventually named governor of the island (with instructions to retake it from the English).

At this moment, everyone who had fled before the invaders faced choices: to fight in the resistance and try to reclaim the island; to surrender to the English and accept whatever treatment they meted out; or to slip away from Jamaica without English assistance. Rejecting all those options, some eventually decided to create another future, withdrawing from all European hostilities while remaining in Jamaica. Their process in coming to that decision cannot be documented, but the broad outlines of their lives can be understood. The Africans living in Jamaica when the English arrived were a mix of free and enslaved individuals. Most had been born on the island or had lived there for decades, spoke Spanish, and worshipped in the island’s Catholic church. Their language skills and high level of acculturation prompted the English invariably to refer to them as “Spanish Negroes,” distinguishing them from Africans who arrived as part of the invasion force or subsequently. Joining with the fleeing Spanish women, children, and elderly, some African refugees slipped away in small boats to Cuba. In doing so, they accepted that their status in Jamaica would carry over to Cuba, and there they would live in a Spanish community as an enslaved or free person, as they had done in Jamaica. Of those who stayed in Jamaica, some fought alongside the Spanish against the English. Others chose to strike out on their own; this group established the first isolated African settlements in the interior, as early as February 1656, some ten months after the English landed. These were not runaway slaves, but rather refugees (both slave and free) pursuing their own strategy against the invaders and eventually in defiance of the authority of Ysassi. Their withdrawal departs from the usual maroon narrative at various points, but especially in that they made that choice collectively. As opposed to runaway slaves—who struck out for freedom alone or in small groups—these individuals gathered as a sizeable group. Their joint decision created the communities they formed and an alternate future for themselves and their children in one dramatic moment.

Both the Spanish and the English were astonished when they realized that some of the refugees had opted out of their struggle altogether to chart their own, separate path. Ysassi, commanding the Spanish resistance, claimed that all the Africans were answerable to him and fighting the English under his command. Yet when the English officer Kempo Sybada, a multilingual Frisian man, happened upon a mounted African, he denied Ysassi’s version of events and claimed complete autonomy for his community. His appears to have been one of a number of independent enclaves of Spanish speaking, predominantly African individuals that coalesced on Jamaica in this period. They came together out of the refugee population and refused to return to slavery or to their lives within Spanish colonial society. Distrusting the English invaders, they created lives away from European colonizers, imperial rivalries, and a world of slavery.

One of these communities would eventually be forced into a relationship with the English government, and we can see through that outcome how it prized its autonomy and self-determination. This connection was forged only after an English party located a village in Lluidas Vale, and threatened to burn its extensive garden crop unless it would help extirpate the Spanish forces on the island. Under the leadership of Juan de Bola, it did so, playing the pivotal role in ending the guerrilla war. After the remaining Spanish departed from the island, de Bola’s community agreed with the English that they would live independently under their own leaders, but would contribute to the English colonial undertaking by serving in the militia (again, under their own officers).

At least in the short term, their deal with the English held. De Bola died in an ambush set by another “Spanish Negro” leader whose community the militia sought to locate and bring under English authority. He and other community leaders received (or regained) houses in Santiago de la Vega, which allowed them to move back and forth between the Vale where the community was centered and the town where their interactions with the English occurred. Far from a case of maroonage, their status represented a different strategy for maintaining freedom and some autonomy under colonial rule.

Other communities—never so unfortunate as to be discovered by the English army—maintained the independent existence they initially chose. At least one other community (and possibly two) remained utterly independent and, despite efforts of the English (aided by de Bola’s troops) to subdue them, they continued as autonomous entities within Jamaica. With similar refugee origins, they presumably became the basis of a future maroon enclave, augmented by increasing numbers of runaways after the English began importing enslaved Africans and Indians. No trace remains to help us understand the transition from the Spanish-speaking refugee communities to a population intermixed with individuals born elsewhere who fled Jamaican slavery. We can only imagine how the refugees and their descendants responded to newly arrived enslaved Africans, people who were unlikely to speak Spanish and who came into the Jamaican interior along a markedly different personal pathway. Out of this complex mix of backgrounds—refugee and runaway—Jamaica’s maroon communities emerged.

Refugee encampments, though they do not conform to the usual narratives of fugitive slaves or outright rebellion, represent another form of resistance. Refugees created autonomous villages and offered another way for Africans in the Atlantic world to seize opportunities to forge a life of their own making. In this case they carved out a space between warring imperial forces, seeing their opportunity to strike out for freedom as a group. Their community formed in an instant—not through a slow accretion of runaways—and they brought to it shared language, culture, and a collective past. Depositing all independent African enclaves into the familiar category of runaway slave maroons reduces the range of African experiences of freedom and struggle in the Americas.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Marisa Fuentes for urging me to write this history in a short and accessible form.

Further Reading

The most comprehensive account of the Jamaica maroons remains Mavis C. Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal (Granby, Mass., 1988). An interesting literary perspective can be found in Cynthia James’s The Maroon Narrative: Caribbean Literature in English across Boundaries, Ethnicities, and Centuries, Studies in Caribbean Literature (Portsmouth, N.H., 2002), 11-14. For treaties between slave-owning authorities and maroons that included provisions for the return of runaways, see Alvin O. Thompson, Flight to Freedom: African Runaways and Maroons in the Americas (Jamaica, 2006), 208-11. My book, The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire (Cambridge, Mass., 2017), reconsiders the English invasion and the resultant refugee exodus and guerrilla war, among other topics. The Anglo-Spanish treaty, negotiated but never adopted (and quoted above), can be found in “Articles of Capitulation at the Conquest of Jamaica, 1655,” Jamaica Historical Review I:1 (1945): 114-15.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4 (Summer, 2017).

Carla Gardina Pestana is professor and Joyce Appleby Endowed Chair of America in the World at UCLA. She writes on religion, empire, and the Atlantic world; her most recent book, published by Belknap, is The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire.

When I started teaching Atlantic World History in 2006, one of the problems I confronted was how to help students grasp the dynamics of Caribbean history in a course that is organized by themes—environmental history, imperial strategies, the slave trade and the African diaspora—rather than by region. I introduce my students to Caribbean geography in a map lecture early in the year, and the Caribbean “sugar and slaves” complex impinges on nearly every unit. But I also hope to give students a vivid sense of the Caribbean’s role as the linchpin of European geopolitical competition in the Atlantic world—and, ideally, accomplish this in just one or two lessons.

The first fact that students of the early modern Caribbean must wrap their minds around is the decimation of the region’s indigenous population, which came sooner, faster, and perhaps more completely in the Caribbean than on the mainland. In class, after students read selections from Alan Taylor’s American Colonies (2001) and Shawn Miller’s Environmental History of Latin America (2007) that deal with this topic, I complicate the story with a two-part exercise. First, students examine a table of population statistics from contemporary North and South America. The nations that report the highest proportions of Native American and mestizo ethnicity today are, for the most part, the regions that had high population density in the pre-Columbian era: Mexico, Guatemala, Ecuador, and Peru. In contrast, Haiti, Jamaica, Cuba, and Brazil report high proportions of African-American ethnicity but tiny proportions of Native American ethnicity—even though the pre-Columbian Caribbean and the Amazon Basin both had sizeable indigenous populations. This contrast makes a good launch pad for a discussion of where most African slaves ended up, and why.

But then the students turn their handouts over to discover a table that charts Puerto Ricans’ ethnic identity in four ways: by self-reporting in the 2000 and 2010 U.S. censuses, by a 2002 study of mitochondrial DNA (which traces deep ancestry in the female line), and by a 2001 Y-chromosome study (which traces deep ancestry in the male line). The data suggest that at least half of Puerto Ricans have Native American ancestry in the female line, but vanishingly few report it, likely because they are themselves unaware of it. African ancestry (which appears in both the maternal and paternal lines) is also underreported, but not to the same degree. As the students consider this table, they develop a vision of a society forged by the blending of European and African blood, in the male line, with Native American and African blood, in the female line. This brief look at contemporary data helps them anticipate the history they will learn.

Several weeks later, toward the end of a long unit on the five major European powers’ colonization styles, we embark on the “Caribbean game,” which I sometimes call “Beyond the Line” in a nod to the principle established by the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559 that skirmishes that occurred west of mid-Atlantic lines of amity would not provoke hostilities in Europe. (Or, to put it more simply, what happened in the Caribbean stayed in the Caribbean.) My unit on colonization styles focuses mainly on the Spanish, Portuguese, and French empires, because those are the ones with which my students are least familiar; they have already encountered the British and Dutch empires in U.S. History. But I make the Caribbean the centerpiece of my brief treatment of British and Dutch colonization, because doing so instills important lessons about those two empires’ priorities: Which American colonies mattered most from a metropolitan British perspective, and how does this explain the relative freedom that mainland colonists enjoyed? Why did the Dutch spread themselves so thinly, and how did they cope with repeated failure, in Pernambuco, New Netherland, and various Caribbean islands? What, ultimately, was the Dutch strategy for gleaning profit from the New World?

The Caribbean game is profoundly simple. On the floor of the classroom, I lay out two dozen hand-drawn cards, each representing a Caribbean island, in a roughly correct map. Cuba’s card is the largest; Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico are smaller; the rest are quite small. Students, assigned to represent various European powers, array themselves around the corners of the map. Teams of two or three students represent the major Atlantic powers of France, Spain, England, and the Dutch Republic; individuals represent lesser powers, such as Denmark and Courland. (“What is Courland?” the students ask. Well, look it up—this is a good lesson that not all countries last forever!) Someone plays the part of “slave uprising,” intimating unrest with drumming, and someone else plays the part of hurricanes, tempests, and other forces of nature.