A Passion for Places: The geographic turn in early American history

If you teach American history outside America, it is very likely that you will have to teach well outside your special area of expertise. Thus, I have often taught twentieth-century American history as well as courses in my specialist area of early America. This year, for example, I teach seminars in American history between 1932 and 1975 while doing courses on early America and on the Atlantic world. On Friday mornings, some students get to overdose on my teaching, as they first listen to my lectures on the Atlantic world then participate in my seminars on mid-twentieth-century American history.

I haven’t asked them how they connect one subject area to the other. The differences, however, between how the two subjects are taught must be immediately apparent. In my courses on early British American and Atlantic history, I range widely over both time and space, with most lectures concentrating on specific geographical areas rather than on topics defined by chronological boundaries. In my seminars on mid-twentieth-century history, however, chronology rules. Seldom pausing to differentiate between the various regions of America (although regional differences in America in the twentieth century were at least as great as in the seventeenth century), we move each week from one decade of American history to the next, from the depressing 1930s, to the dull 1950s, to the exciting 1960s, ending back in depression with the 1970s.

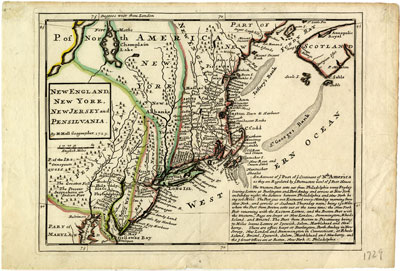

My teaching methods are hardly unusual. Indeed, these frameworks—thematic and regional for early America, chronological for the history of the United States—are normal for teaching these subjects. Look at any textbook on American history. All textbooks devote considerable attention to the colonial period. But more often than not, chapters on colonial life overlap in time. In George Brown Tindall and David E. Shi’s conventional summary of American history, for example, the colonial period is treated in three separate chapters: one concentrating on regional differences in settlement, one on colonial ways of life, and one on politics and empire. The textbooks are designed to get students to be able to compare and contrast colonization in, say, Barbados, Virginia, and Massachusetts before 1660 or to be able to explore how consumption patterns shaped colonial social patterns.

Specialist synthetic works also use region as a principal explanatory device. I use Jack P. Greene’s Pursuit of Happiness, Jon Butler’s Becoming America, Alan Taylor’s American Colonies, and Steven Sarson’s British America 1500-1800. Greene, Taylor, and Sarson all pay some attention to chronology but only within the context of regionalism. Each deal in turn with settlement in the Chesapeake, New England, and the West Indies before dealing with later-settled colonies in the lower South and the mid-Atlantic. It is only in the eighteenth century that they treat colonies all together. Butler’s book collapses time into theme, with chapters on social, political, economic, and religious trends. A similar approach is taken in David Armitage and Michael Braddick’s influential The British Atlantic World 1500-1800. Each essay in their collection covers thematic topics. The overall effect must seem strange to students of later American history. Region is hardly unimportant in twentieth-century history—the South, in particular, usually gets separate treatment in any survey—but to organize the history of the twentieth century as the history of seventeenth-century America is usually organized, with region (the West, the North, the South) and even theme being the primary category of organization would be distinctly strange.

Moreover, the most dynamic areas within contemporary early American historiography—the Atlantic World, the Middle Ground—are defined primarily by geography. Except for a few microhistorical investigations of specific events in specific places where the emphasis is on recreating lost worlds frozen at a particular point in time, almost all books on early America range widely over time and sometimes place. Look at the books published in recent years in the prestigious Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture series. Apart from books on the revolutionary period by Christopher Brown and Michael McDonnell, where close attention is paid to chronology, other monographs published in 2006 and 2007 deal with topics that span centuries. Emily Clark’s book on the New Orleans Ursulines ranges from 1727 to 1834, and Clare Lyon’s book on sex and gender in Philadelphia covers almost exactly the same time span. Brendan McConville’s account of monarchalism in early America extends from 1688 to 1776, while Susan Scott Parrish’s tale of American natural history is about the whole of the colonial period. Martin Bruckner’s book on geography and American literature and Sharon Block’s investigation into early American rape are similarly temporally wide ranging.

Why are early Americanists so obsessed with region—with geography, in short—rather than with chronology? Why is early America generally organized by space rather than time, at least until the Revolution comes along? In part, of course, the reason for such fixation upon space is because the colonial period is the very important prologue to the main event, which is the formation of the nation state and of United States history proper. The colonial period is thus the medieval section of American history. Chronologies matter less because there are fewer events of importance (Tindall and Shi list only three events occurring between Salem in 1692 and 1736 in their timeline of the eighteenth century—the Yamasee War of 1715-1717, the settlement of Georgia in 1733, and the Zenger trial of 1735). Moreover, colonial Americanists are allotted less teaching time in college courses than are their United States historian colleagues, thus discouraging close attention to specific events. Just imagine what damage would be done to the first year American history survey if early Americanists insisted on devoting separate lectures to each decade of the early eighteenth century, our lectures on the 1730s, 1740s, and 1750s paralleling those given by our twentieth-century colleagues on the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Instead, most early Americanist teachers, in the American history survey, do the whole of the long eighteenth century in either one or perhaps two lectures of breathtakingly wide scope. Early America is also treated very broadly in academic works. The two forthcoming volumes on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American history to be published in the Oxford History of the United States each cover over ninety years. The remaining nine volumes in the series each cover no more than one generation’s experience. Two—those on the Civil War and on the Depression and World War II—deal with fewer than twenty years of American history. If all periods of American history were to be covered equally in depth in this series, then there would need to be at least five volumes on prerevolutionary America.

Early Americanists’ privileging of space over time is so natural as to be almost reflexive. I remember very well putting on a conference for early Americanists where the specific theme was chronology. I hoped, in vain as I knew would be the case, for proposals on specific decades—the 1610s, or 1690s, or 1730s, for example. I still think it would be a useful exercise for early Americanists to concentrate attention on studying all of British America or even all of Atlantic America in small periods of time. It would be useful to differentiate what happened in the 1640s from what had occurred in the 1630s and to make a distinction between British America in the 1720s and British America in the 1740s or 1750s. But, as one might expect, my hopes were not fulfilled. People interpreted chronology through a prism of regionalism—what happened in Virginia, for example, in the first half of the seventeenth century or in Pennsylvania in the mid-eighteenth century. Like medievalists, early Americanists are accustomed to working over whole centuries or at least half centuries and find shorter time periods as well as larger geographical contexts difficult to deal with. The scholarly debate that modern Americanists have over when the 1950s became the 1960s has no counterpart in early American history.

Early Americanists’ devotion to geography may seem normative (it is seldom questioned, at any rate), but it is distinctly odd when compared to other historiographies concentrating on the same time periods as colonialists do. Historians of early modern and eighteenth-century Britain, for example, tend to organize their histories around chronology. Julian Hoppit’s volume on English history between 1689 and 1727 in the New Oxford History of England, for example, starts with a close examination of the Glorious Revolution settlement before an investigation of social realities. Little attention is given to regional differences per se. Penry Williams in his volume in the same series on the later Tudors is similarly concerned with outlining the principal events of the reigns of Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth before looking at the social history of the period. He hardly does region either. Attention to chronological markers makes sense for a discipline in which early modern history gets as much attention as modern history: the number of years covered in the four volumes in the series dealing with the history of England from 1547 to 1727 is eleven years less than in the four volumes dealing with English history from 1727 to 1918. But even in the more expansively treated medieval period, chronology takes precedence. Moreover, early modern English historians often pay close attention to chronological narrative, as can be seen in their treatment of the English Civil War. John Adamson’s nearly six-hundred-page analysis of the causes of the crisis of 1641-2 and David Cressy’s nearly five-hundred-page narrative of the same years has no counterpart in early American history until we come to studies of the Revolution or the Constitution.

So why are early Americanists so concerned with geography when their peers in United States history and early modern British history concentrate on chronology? It is mostly to do with how the subject has developed in the last half century—a half century, it should be noted, where early American history went from being “a neglected subject” in the words of Carl Bridenbaugh, first director of the Institute of Early American History in a jeremiad issued in 1947—to being an especially dynamic and innovative area of scholarship. The two most noticeable transformations have been the move in the 1960s and 1970s towards “new social history,” in which the customary methodological and geographical boundaries of early American history were greatly extended, and the recent move to Atlantic history, in which early American history was folded into a larger historical geographic project linking North America with other continents surrounding the Atlantic ocean. The connections between the two movements are close. As Bernard Bailyn argues, the sheer profusion of social-science inflected work on ever narrower topics made “discrete and easily controllable” fields of knowledge “boundless” and “incomprehensible” with coherence being the principal casualty. The analytical device of the Atlantic World (and the Middle Ground paradigm for more continentally minded scholars) allowed many disparate studies to connect more closely. Of course, that is Bailyn’s view. Other historians disagree about his particular analysis of the crisis in early American history and his use of an Atlantic-world paradigm to bring order to a disordered historical universe. What is clear, however, is that in the move from one kind of historical writing to another, what has been retained has been a concentration on geography. A central concern of early American historians writing in the last thirty years had been to expand the geographical scope of the subject, so that no one with a serious interest in early America could ever again blithely assume that the United States was just an extension over time of the New England Way.

The most important message that came out of the “new social history” of early America, beside the utility of using methods drawn from social-science disciplines to explore early American mentalities, was that colonial British America was geographically diffuse. One of its achievements was the naturalization of region as the best explanatory framework within which the diffuseness of early America could be assessed. Indeed, Jack Greene and J. R. Pole, in their introduction to Colonial British America—an immensely influential 1984 collection of essays, which marked the highpoint of “the new social history” period in early American history—specifically prioritised region as the building block upon which a general developmental framework of colonial history could be built. The advent of Atlantic, Middle Ground, and borderlands perspectives as operating paradigms for early Americanists has only increased our dependence on region as a way of understanding early America, even if nowadays the boundaries between regions, or the fuzziness of those boundaries, draws as much attention as the regions themselves.

Indeed, what is remarkable about recent developments in early American historiography, notably the rush towards seeing everything in an Atlantic context, is how the geographical focus of the “new social history” has not only been retained but has been enhanced. Indeed, I would argue that Atlantic or borderlands histories (both in themselves geographical terms) are convincing evidence of a longstanding geographical turn in early American history, a more long-lasting and more influential turn than more heralded turns towards theory, towards linguistics, and towards anthropology. If anything defines early American history today, it is its relentless geographical focus. It is space, not time, that dominates our attention.

Early Americanists, it is true, have begun to think differently about space as they try to connect the themes of Atlantic and Middle Ground history—the movement of goods, ideas, and people for the former; the contestation of space by different cultures in the latter—to older understandings of regional and cultural difference. They are trying to move beyond seeing space in terms of region or nation or even empire—rigid structures bounded by artificial political boundaries—into seeing space as multiple if networked sets of colliding trajectories. They are interested in seeing connections, collisions, and interactions between different places in ways that illuminate the distinctive features of certain places. In this process, it is the points of connection, the movements and sharp contacts between places that are most interesting, rather than the places that result from colliding geographical trajectories.

What does this mean for practicing early American historians? It mostly means reading more history about other parts of the world. The most noticeable feature of the geographical turn in early American history has been a greater than normal involvement with the work of other historians in cognate fields. It has expanded our horizons, extending our historical geographical reach, and narrowed our focus: the time we spend reading other histories is time we are not spending catching up with developments in other disciplines. Maybe I am speaking only for myself, but I find I am increasingly absorbed in trying to master the historical literatures of many parts of the world, from Europe to Asia to the Americas, and sometimes even of the world itself. Here are a few of the books that have been shaping my thought in the past year. I have read Sir John Elliott’s Empires of the Atlantic World, a masterly comparison of Spanish and British America. I have read P. J. Marshall’s The Making and Unmaking of Empires, comparing British imperialism in India and America, which has led me on to reading a number of other histories of eighteenth-century India by Nicholas Dirks, Robert Travers, and Durba Ghosh. I followed up reading Huw Bowen’s account of the East India Company in Britain with Brendan Simms’s massive international history of Britain’s wars in eighteenth-century Europe and America, Three Victories and a Defeat. Two quite different works—Linda Colley’s engrossing work on the picaresque life of Elizabeth Marsh, “a woman in world history,” and David Armitage’s brilliant exposition of the worldwide impact of the Declaration of Independence—make me try to link events in the Americas to global history. Meanwhile, Robin Law’s history of Ouidah in the period of the slave trade and John Thornton and Linda Heywood’s account of how vital central Africans were to the making of early African American culture point out how we need to understand African history in order to understand early American history. To get a grip on events in the metropolis in years that were crucial years of transition in early America, I read Tim Harris’s two-volume history of the Glorious Revolution, while in order to work out what was occurring in British society that explains the rise of moral authoritarianism in the latter part of the eighteenth century, I have found Vic Gatrell’s City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London insightful. I could go on and list the contents of my library at tedious length but you get the idea. In order to understand my own topic, I need to try and connect my area of expertise with what was happening elsewhere in the world at the same time.

Of course, what is noticeable about this list—one that is eclectic but as a list of reading outside my specialty is probably typical of the type of wider reading that is now customary for early Americanists—is that while it ranges widely over space, it is also reading that is narrowly confined to the discipline of history. It reflects wider changes in the discipline whereby early Americanists have concentrated on expanding their knowledge of historical geography at the expense of reading in other disciplines.

An examination of the early American house journal, The William and Mary Quarterly, bears out these claims. There has been a noticeable drop-off in articles in that journal that pay more than lip service to theory or that show deep reading in disciplines other than history. The exception might be in political thought, which continues to be a subject in which many historians show an interest. But work indebted to anthropology, sociology, and above all economics, all mainstays of the previous “new social history” period, is thin on the ground. Historians of native America have close interactions with anthropologists but not often with anthropologists working in other areas of the world or in other topics besides ethnohistory. For most early Americanists, the 1970s love affair with anthropology has faded. In addition, economic history (in America increasingly done by economists with an interest in history rather than historians with an interest in economics) has gone from being the darling of early American history to being considered rather old-fashioned. We are mostly cultural historians now, as Peter Coclanis lamented in a savage review of treatments of early American slavery that do not employ social-scientific methods in order to ascertain representativeness, which appeared in July 2004 in The William and Mary Quarterly.

At the same time, however, this early Americanist house journal is surprisingly willing to publish articles about geographical areas that lie outside the brief of a journal devoted to the history and culture of British America and those parts of the Americas that later became part of the United States. There have been special issues since 2000 devoted to race and religion in New Spain and to the Atlantic economies of the mid-eighteenth-century Spanish Caribbean. Recent forums in the journal have all been about expanding the spatial, rather than the theoretical, boundaries of the field. It makes early Americanists remarkably ecumenical about the spatial boundaries of their field. Indeed, recent forums devoted to ongoing historical trends have tended to urge early Americanists to widen their spatial boundaries even further than at present. One typical forum was “Beyond the Atlantic,” in October 2006, where several commentators argued for an extension of the Atlantic world concept into British Asia and even into global history. Another formed around a discussion of Jack P. Greene’s provocative polemic in April 2007 in which he argued that early Americanists should take the lead in reshaping later American history around the postcolonial narratives that colonial Americanists have imbibed, placing American history within broader global contexts of comparison and conjunction and encompassing geographies beyond the nations state.

All this is to be applauded. Unlike nation-state fixated historians of the United States, who in my opinion find it impossible to ditch narratives of American exceptionalism for internationalist narratives, early Americanists are at least prepared to contemplate a world beyond America where history happened and where history continues to be read. Early Americanists, in my experience, are less likely than historians of the United States to engage in an egregious practice that always sets my teeth on edge, as a non-American doing American history outside of America. This is the practice of using exclusionary language about the reading audience (“We Americans,” as Gordon Wood proclaims in the first line of his Pulitzer Prize winning history of the American Revolution’s impact), which not only excludes as readers all people who don’t happen to have the fortune to be born American but which also assumes that American history is an internalist history, separate from histories of other places in the world. Early Americanists based in the United States still do use such exclusionary language, unable to envision an audience for American history that exists outside America. But the use of such exclusionary language is less pervasive in early American history than in later American history. I could quote chapter and verse on this depressing trend in American historiography but that might be the subject of a separate diatribe.

Still, there is something very curious about early Americanists’ determination to use space rather than time as the basis for our studies. We have become historical geographers but have done so by reading history rather than geography. Geographers read us (and rather well, as it turns out, as can be seen in works by the British historical geographers Alan Lambert, David Lambert, and Daniel Clayton, all of whom are interested in colonial spaces), but we don’t read them. It is remarkable how little attention is paid by early Americanists to what geographers might say about space and place, despite our knowledge that we need to think differently about space than we did when space meant politically bounded regions conceived of as static entities rather than fluid places of movement. I looked at articles in The William and Mary Quarterly published this century to see which geographers are cited. Apart from D. W. Meinig—whose work on Atlantic America has been immensely influential for the development of Atlantic history but whom Atlantic historians read mostly as a historian rather than a geographer—the only geographical work mentioned is Martin W. Lewis and Kären E. Wigen’s The Myth of Continents. Examining what geographers have to say to historians is beyond the brief of this article. But early Americanists should make more of an effort to interrogate their assumptions about space. They might find what geographers have to say about space and place useful starting points for reflections upon the unceasing desire of early Americanists to expand the spatial frontiers or boundaries of their subjects. We might take on board the sensible comments of Alan Baker, author in 2003 of an excellent meditation Geography and History: Bridging the Divide, not often cited by early Americanists, noting that the epistemological foundations of the two subjects are sufficiently different for historians not to assume that historical geographers are just historians masquerading under another name. We might also pay more attention to Felix Driver’s work on imperial landscapes when trying to make sense of how empires shaped Atlantic worlds. I find Doreen Massey’s musings in her important 2005 book, For Space, especially insightful about how to escape the limitations of historically and geographically bounded notions of place. She notes how in traditional historical writing, space is thought of in an essentialist fashion—”first the differences between places exist, and then those different places come into contact.” The differences we see, she suggests, “are the consequence of internal characteristics,” leading us to a “billiard-ball,” “tabular conception of space.” Instead, she postulates, we might think of space as “the sphere of a multiplicity of trajectories.” A trajectory—people, objects, texts, ideas—is not bounded but is defined by movement. Geography is created when different spatial trajectories come together. The differences between places are what happen when trajectories intersect in varied ways across the surface of the earth. Massey’s view of space as constellations of multiple trajectories allows for space to be thought of not in tabular form but as relational constructions. We don’t so much “belong” to a place but “practice” place through the negotiation of intersecting trajectories.

There is much here to think about. What Massey says is not easy for historians to understand, in part because she resists what we do all the time, which is to turn geography into history, space into time. As she argues, “for me, one important aspect of space is that it is the dimension of things (and people) existing at the same moment. If time is the dimension of change then space is the dimension of simultaneity.” Space and time are thus necessarily different. Geographers look at how, in space, all sorts of things happen at once. Historians examine how, through time, change is effected.

Historians might not find Massey’s ideas about trajectories very helpful. They may prefer the insights of other geographers than the few geographers, all British, noted here. That is of little matter. What is important, however, is that we start to think as seriously about space as we always have thought seriously about time. If there has been a geographical turn in early American history, and I am sure there has been, then we may need to pause in our relentless quest to find more and more histories that intersect with the histories we ourselves are writing; in that pause we ought to consider what we are doing when we are trying to connect two or more spaces or places together. Perhaps we should remember that the historians who did such great things in that golden period of the “new social history,” when early American historians led the way in developing fresh ways of approaching historical topics, did so through intense engagement with other disciplines. Perhaps it is time, once again, to look at what other disciplines might have to offer us as we widen our historical horizons. If early Americanists are indeed becoming historical geographers, almost by default, we might want to think as hard about the geography part of that noun as about the history part.

Further Reading:

Works mentioned in this article are, in alphabetical order: John Adamson, The Noble Revolt: The Overthrow of Charles I (London, 2007); Fred Anderson and Andrew Cayton, Imperial America, 1674-1764, Oxford History of the United States (New York, forthcoming); David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (Cambridge, Mass., 2007); David Armitage and Michael Braddick, eds., The British Atlantic World, 1500-1800 (New York, 2002); Bernard Bailyn, “The Challenge of Modern Historiography,” The American Historical Review 87:1 (February 1982): 1-24; Alan Baker, Geography and History: Bridging the Divide (Cambridge, 2003); Sharon Block, Rape and Sexual Power in Early America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); H. V. Bowen, The Business of Empire: The East India Company and Imperial Britain, 1756-1833 (Cambridge, 2006); Carl Bridenbaugh, “The Neglected First Half of American History,” The American Historical Review 53:3 (April 1948): 506-517; Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); Martin Brückner and Hsuan L. Hsu, American Literary Geographies: Spatial Practice and Cultural Production, 1500-1900 (Newark, N.J., 2007); Jon Butler, Becoming America: The Revolution Before 1776 (Cambridge, Mass., 2000). Emily Clark, Masterless Mistresses: The New Orleans Ursulines and the Development of a New World Society, 1727-1834 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2007); Daniel Clayton, Islands of Truth: The Imperial Fashioning of Vancouver Island (Vancouver, BC, 2000); Peter Coclanis, “The Captivity of a Generation,” review of Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves, by Ira Berlin, William and Mary Quarterly 61:3 (July 2004): 544-556; Linda Colley, The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A Woman in World History (New York, 2007); David Cressy, England on Edge: Crisis and Revolution, 1640-1642 (Oxford, 2006); Nicholas Dirks, The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain (Cambridge, Mass., 2006); Felix Driver and David Gilbert, Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity (Manchester, UK, 1999); John Elliott, Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America, 1492-1830 (New Haven, 2006); “Forum: Beyond the Atlantic,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 63:4 (October 2006); “Forum: The Middle Ground Revisited,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 63:1 (January 2006); Vic Gatrell, City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London (New York, 2007); Durba Ghosh, Sex and Family in Colonial India: The Making of Empire (Cambridge, 2006); Jack P. Greene, Pursuits of Happiness: The Social Development of Early Modern British Colonies and the Formation of American Culture (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1988); Jack P. Greene, “Roundtable-Colonial History and National History: Reflections on a Continuing Problem,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 64:2 (April 2007): 235-251; Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, eds., Colonial British America: Essays in the New History of the Early Modern Era (Baltimore, 1984); Tim Harris, Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685-1720 (London, 2006); Julian Hoppit, A Land of Liberty?: England, 1689-1727 (Oxford, 2000); David Lambert and Alan Lester, Colonial Lives Across the British Empire: Imperial Careering in the Long Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, 2006); Robin Law, Ouidah: The Social History of a West African Slaving ‘Port’: 1727-1892 (Athens, Ohio, 2004); Martin W. Lewis and Kären E. Wigen, The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography (Berkeley, 1997); Clare Lyons, Sex Among the Rabble: An Intimate History of Gender and Power in the Age of Revolution, Philadelphia, 1730-1830 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); P. J. Marshall, The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America, c. 1750-1783 (Oxford, 2005); Doreen Massey, For Space (London, 2005); Brendan McConville, The King’s Three Faces: The Rise and Fall of Royal America, 1688-1776 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); Michael McDonnell, The Politics of War: Race, Class, and Conflict in Revolutionary Virginia (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2007); D. W. Meinig, The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History: Volume I, Atlantic America, 1492-1800 (New Haven, 1986); Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); Steven Sarson, British America, 1500-1800: Creating Colonies, Imagining an Empire (New York, 2005); Brendan Simms, Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714-1783 (London, 2007); “Special Issue: New Perspectives on the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 58:1 (January 2001); “Special Issue: Slaveries in the Atlantic World,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 59:3 (July 2002); Alan Taylor, American Colonies (New York, 2001); John Thornton and Linda Heywood, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660 (New York, 2007); George Brown Tindall and David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History, 7th ed. (New York, 2006); Robert Travers, Ideology and Empire in Eighteenth-Century India: The British in Bengal (New York, 2007); Penry Williams, The Later Tudors: England, 1547-1603 (New York, 1995); Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815, Oxford History of the United States (New York, forthcoming); Gordon S. Wood. The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York, 1992).

This article originally appeared in issue 8.4 (July, 2008).

Trevor Burnard has had a peripatetic career, teaching at universities in the West Indies, his native New Zealand, and in England. He is professor of the history of the Americas at the University of Warwick and will be Archie Davis Fellow at the National Humanities Center in North Carolina in 2008-9. He is working on a jointly authored work on mid-eighteenth-century Jamaica and Saint Domingue. He has written books and articles on the eighteenth-century Chesapeake and Jamaica.

![Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii alioru[m] que lustrationes, Martin Waldseemüller, (1507). This digital image is a composit map (128 x 233 cm.) from twelve separate sheets (46 x 63 cm. or smaller). Courtesy of the Geography and Map Division of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Click to enlarge in new window.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/9.2.Sayre_.2-300x167.jpg)