Memory as History, Memory as Activism

The Forgotten Abolitionist Struggle after the Civil War

Before the Civil War, abolitionists produced a vast “movement literature” of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and slave narratives; after the war, they published memoirs of their lives and work. For a long time, however, it was unfashionable among historians to take abolitionists at their word. Abolitionist reminiscences especially were caricatured as self-aggrandizing, hagiographic, and unreliable historical sources. It was even worse in popular culture, where abolitionists were demonized as fanatics who had caused an unnecessary war and African Americans were depicted as racially inferior and unprepared for freedom. As Julie Roy Jeffrey points out in her recent book, abolitionists wrote their recollections at the moment the gains of Reconstruction were being undone. As the emancipationist view of the Civil War was buried beneath the romance of reunion and sectional reconciliation among whites, both the reputation of abolitionists and the rights of black people lay in tatters. Abolitionists started publishing their recollections, not only to set the historical record straight but also to draw attention to the new racial reign of terror in the post-war South. Just as they had used memories of a revolutionary past to struggle for the abolition of slavery, they deployed abolitionist memory to resuscitate the fight for black rights. But abolitionist memoirs were isolated voices crying in the wilderness. Subsequent commemorations of the Civil War typically ignored its most consequential result, emancipation, and the role of African Americans and abolitionists in bringing it about.

Today, as we mark the sesquicentennial of emancipation and the war, the abolitionists are once again the forgotten emancipationists, whose part in the process of emancipation is at best neglected, or at worst reviled. In popular culture, as in the movie Lincoln, one or two abolitionists depicted by Radical Republicans play a supporting role in the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment that abolished slavery. Recent academic assessments—for example, Andrew Delbanco’s The Abolitionist Imagination (2012)—have revived the old view of abolitionists as destructive fanatics. It is high time that we paid some attention to the forgotten abolitionist struggle after the Civil War, which sought to construct a different memory of the struggle against slavery and the legacy of emancipation. A close look at abolitionist memoirs reveals the rich interplay between history, memory, and activism and challenges the idea that abolitionists were largely self-congratulatory and unconcerned with the plight of emancipated slaves. While many abolitionists wrote public documents in an attempt to shape the national memory of the war and emancipation, others retreated to personal reminiscences in a world unremittingly hostile to the idea of racial equality.

Most abolitionists published their reminiscences at the turn of the century during the nadir of black history when disfranchisement, racial violence, and segregation made a mockery of black freedom.

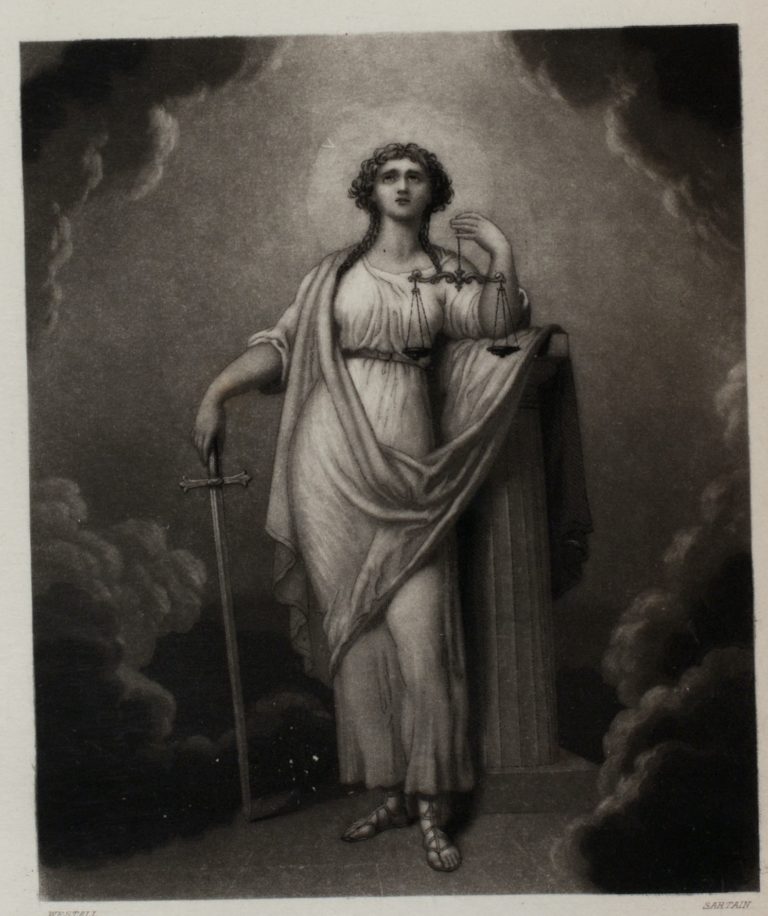

As gratifying as emancipation and the constitutional amendments guaranteeing black citizenship had been, abolitionists remained quintessential protestors throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Samuel J. May, an early convert to Garrisonian abolition, was a pioneering figure in the attempt to write a history of abolition in light of America’s revolutionary past. But May’s recollections, published in 1869, were no triumphal narrative. Instead, he remained critical of the founding fathers of the country. The “shameful facts” of history revealed that “(notwithstanding their glorious Declaration) the American revolutionists did not intend the deliverance of all men from oppression” and that the Constitution did not “secure liberty to all the dwellers in the land.” To truly comprehend the magnitude of the abolitionist task and emancipation, May argued, one must understand the “terrible fact that the American Revolutionists of 1776 left more firmly established in our country a system of bondage.” In short, the Civil War and the remaking of the U.S. Constitution had been necessary to correct these mistakes of the revolutionary era and purge the country of slavery.

Unlike later historians who have always looked at the first wave and second wave of abolition as distinct movements, May wrote a complete history of abolition that left out no period or group of actors. Though the bulk of his book focused on antebellum abolition, May began his study with the Pennsylvania Quaker abolitionists of an earlier generation and looked at abolitionists who had preceded Garrison, such as Benjamin Lundy. Though a Garrisonian, he developed portraits of political abolitionists James G. Birney, Gerrit Smith, and John G. Whittier. And unlike subsequent generations of “objective” historians, he included women such as Lydia Maria Child and Lucretia Mott, and especially black abolitionists James Forten, Robert Purvis, David Ruggles, Frederick Douglass, Lewis Hayden, William Wells Brown, Charles Lenox Remond, and Jermain W. Loguen. Anticipating recent scholars, May recalled the transatlantic connections forged by abolitionists in Britain. Hardly a simple hagiography, his work captured the diverse, cosmopolitan, and radical nature of American abolitionism. May closed his book with John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry and the anti-abolitionist riots in Boston on the very eve of the Civil War, refusing to let the North appropriate the abolitionist project and bask in the glory of a victorious war. He made the common abolitionist accusation that most northern whites had been partners in crime with southern slaveholders. And after the war, he noted, freed people had been left “at the mercy of their former masters.” They should have been given homes, “adequate portions of the land (they so long have cultivated without compensation),” and education. The nation, he wrote, had yet to learn from “the sad experience of the past.” This was not self-congratulation run amok, but a sobering reminder of the hard work of freedom. Through his comprehensive account and his reflections on the founding fathers, May tried to construct a more historically accurate portrait of the abolitionist movement to counteract the unsympathetic history that was rapidly becoming entrenched in national memory.

Ten years later, when Reconstruction was overthrown, Oliver Johnson attempted to do the same, but through biography. Johnson, who at one point or another had edited nearly all the prominent Garrisonian newspapers during the antebellum period, published his William Lloyd Garrison and His Times: or, Sketches of the Antislavery Movement in America, dedicated to the “surviving heroes of the Anti-Slavery struggle.” This account of the abolition movement ended with Garrison’s death and an appendix of eulogies and poetry dedicated to him. As Wendell Phillips (who had disagreed with Garrison on the continuation of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1865) put it, abolitionists did not gather to weep over or praise Garrison but to learn the great “lesson” of activism from his life. Phillips credited Garrison, the master of the “nature and needs” of “agitation,” for awakening him to a “moral and intellectual life.” He yearned for that “clear-sighted” activism at a time when men “judge by their ears, by rumors; who see, not with their eyes, but with their prejudices,” an evocative description of the growing blindness of the nation to the condition of former slaves. In his last essay on Garrison, Johnson defended the former’s unconventional religious views from contemporary critics. Garrison was not, he wrote, a “degraded infidel.” Some abolitionist reminiscences like Johnson’s were clearly fashioned as eulogies, in which the deceased’s contributions could be recalled and served as a spur to renewed action. They lent a sense of urgency to those who felt compelled to write their memoirs when many lived long enough to see every victory won undone.

Most abolitionists published their reminiscences at the turn of the century during the nadir of black history when disfranchisement, racial violence, and segregation made a mockery of black freedom. In his Anti-Slavery Days (1884), James Freeman Clarke complained that American children were taught about Egyptian slavery but “very little about the colored people of the United States.” Parker Pillsbury’s Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles (1883) tellingly concluded with his speech at the 1865 meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, when he argued that the society’s work was not complete until black equality was achieved. Pillsbury sought to evoke the heroic struggles of the movement at a time when the abolitionist project was once again unpopular, despised, and disputed. Aaron M. Powell dedicated his reminiscences (published in 1899) to the young people of the country so that they may be inspired by the abolitionist struggle to renew the fight for racial equality. Some abolitionists simply gave up. Memoirs such as Henry B. Stanton’s Random Recollections (1887) marked the author’s distance from his early abolitionist commitment, while others like Giles Stebbins’ Upward of Seventy Steps (1890) evoked a variety of other causes: the conflict between labor and capital, spiritualism, temperance, and women’s suffrage.

The recollections of abolitionist women not only sought to resuscitate the reputation of abolitionists but also to rekindle the fight for black and women’s rights. The 1891 Anti-Slavery Reminiscences of Quaker abolitionist Elizabeth Buffum Chace, for example, daughter of the pioneering immediatist Arnold Buffum, is not a passé recital of the evils of slavery but instead highlights egregious instances of northern racism, a timely reminder for the post-Reconstruction nation. None but “long-tried abolitionists,” she wrote, understood “the necessity of all removal of race prejudice, and the establishment of the principle of common humanity.” It was a “baneful” policy to maintain “two nationalities” in the United States, the continuing refusal of the nation to recognize black citizenship. In the process of “overthrowing one great wrong,” she concluded, other “wrongs” had been revealed that required the same kind of abolitionist dedication as the fight against slavery. At a time when an entire generation of abolitionists was dying off, Chace’s call was a forlorn cry for anti-racism and activism that she saw represented only in the contemporary woman suffrage movement.

Like Chace, Sarah Southwick was a Quaker who traced her abolitionist leanings to family history: her grandfather had been a correspondent of British abolitionist James Cropper, and her parents were committed abolitionists. Her father began subscribing to The Liberator when she was just ten years old, and her uncle Isaac Winslow was an early Garrisonian abolitionist. She was, as she put it, “born into the cause.” Southwick paid special attention to women’s activism in the abolition movement in her 1893 narrative, recalling prominent women abolitionists such as Lydia Maria Child, Maria Weston Chapman, members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, and the annual antislavery fair they organized. Clearly, for Southwick the fight against “prejudice against color” had been an important facet of abolitionist activism, though unlike Chace she wrote little about the contemporary condition of freed people. Clearly meant for private consumption, Southwick’s memoir was privately published and mainly a “personal” account. Her response to the increasingly hostile public memory of the war and emancipation that either ignored or criticized abolitionists was a retreat to personal memory.

For abolitionists, the ongoing reversal of their wartime gains made for a narrative of defeat rather than triumph. The dual purpose of vindicating the abolition movement and black rights in an increasingly reactionary era permeated the memoirs of abolitionists. They made it clear that the aims of abolition had not been realized. Unlike Southwick, Lucy Colman, who had worked in a black school before the Civil War and with freed people during and after the war, wrote a memoir intended for public consumption. She concluded her 1891 book with an abolitionist lament: “But who pays the slave for his sufferings? In this interminable talk of compensating the slave-owner for his losses, who ever thought of paying the slave for the loss of a lifetime? We are none of us very patient of wrongs done by those whom our race defrauded of everything but life itself, and often of that.”

Although abolitionist memoirs were not widely read, the most popular and contested sub-genre were works by abolitionist authors detailing their experiences with the underground railroad (UGRR). The roots of the contemporary fascination with the exploits of the UGRR can be traced directly to the post-war period. Since much of this work, helping slaves escape to freedom, had been against the law, it is only after the Civil War that abolitionists started publishing accounts of their underground activities. Indeed, one of the reasons modern historians have been so dismissive of the abolitionist underground is because they have seen as it as merely the stuff of myth and memory perpetuated by erstwhile abolitionists with an inflated sense of their own importance. But increasingly scholars working on the UGRR are finding these memoirs to be of significant historical importance.

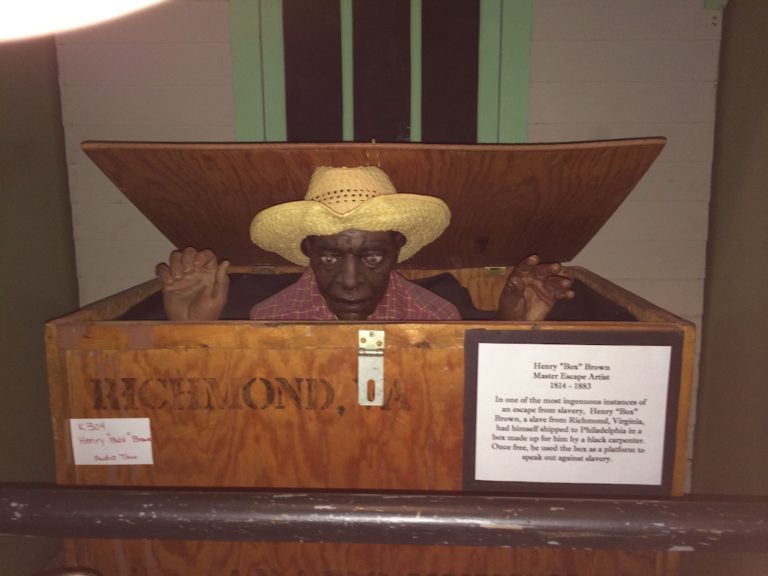

William Still’s seminal The Underground Railroad (1872) placed black activism—fugitive slaves as well as their “self emancipated champions”—at the center of the history of abolition. Still’s book is a treasure trove of accounts of the famous and not so famous fugitives who passed through the hands of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, of which he was a long-time secretary. It is a work of abolitionist memory in many layers, containing the stories of enslaved men and women, prominent abolitionists, as well as Still’s remarkable personal family history of enslavement and freedom. Like other erstwhile abolitionists, he hoped to draw contemporary political lessons by documenting the history of the abolitionist underground. As Still put it, he wanted to “testify for thousands and tens of thousands,” especially during the waning days of Reconstruction when “the hopes of the race have been sadly disappointed.” He raised the question whether “political progress” was possible at all in the “face of the present public sentiment.”

Stories of the underground railroad were popular because they allowed northern readers to vicariously participate in the deliverance of fugitive slaves; this reader response contributed to the mythic quality surrounding its history. Luminaries of the abolitionist underground such as the Quaker abolitionist Levi Coffin, the reputed “president” of the UGRR, published his reminiscences but also tied his antebellum work with fugitive slaves to his activism on behalf of freed people after the war. For Coffin, abolitionist “jubilee meetings” became fundraising tours for “the relief of freedmen in our district of labor.” Coffin’s reminiscences appended memoirs of two other abolitionists: the young Quaker Richard Dillingham, who died in a Tennessee prison, and Calvin Fairbank, who spent much of his life behind bars in Kentucky after being accused of running off slaves. Coffin felt moved to write because many of his “co-laborers had passed away,” and he felt that he “must soon follow.” In fact, the third edition of his book, as was becoming the norm in abolitionist memoirs, contained an account of his death and funeral.

Coffin died with the sanguine expectation that the government would carry on the relief work on behalf of freed people inaugurated by abolitionists, but his co-worker, the pioneering western abolitionist Laura Haviland, lived long enough to see those plans unravel. Like Coffin, Haviland linked her activism in the abolitionist underground with advocacy for the emancipated slave. During and after the Civil War Haviland, like many abolitionists, had been active in freedmen’s relief and the Freedmen’s Aid Commission. Haviland devoted the last third of her autobiography—titled A Woman’s Life-work: Labors and Experiences of Laura S. Haviland (1881)—to the atrocities against freed people and her vindication of the Kansas “exodusters.” As she put it, “After fifteen years of patient hoping, waiting, and watching for the shaping of government, they saw clearly that their future condition as a race must be submissive vassalage, a war of races, or emigration.” Coffin and Haviland both viewed the fight for black rights after the Civil War as a continuation of the grassroots activism that had characterized the “practical” work of the UGRR.

Many others less known than Still, Coffin, and Haviland wrote of their experiences with the abolitionist underground. One of these was Alexander Milton Ross, a Canadian abolitionist inspired by fugitive slaves in Canada and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He published his “Recollections and Experiences” in 1875 and dedicated it to Tsar Alexander II for abolishing serfdom. In his very first visit to Richmond, Virginia, Ross reported that forty-two slaves met him at the house of a reliable “coloured preacher” to discuss the possibility of escape. Ross went on to describe many other instances of enslaved people fleeing the South, at one point meeting a “poor” and “laboring” black man who held in his hand a notice of the $1,200 reward for his capture. An ally of John Brown, Ross counted himself in the ranks of those abolitionists who acted rather than merely wrote and spoke against slavery. Toward the end of his career in the abolitionist underground, Ross even managed to penetrate the Deep South, traveling to South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, coordinating slave escapes. During the war Ross, like some other abolitionists, acted as a spy for the Union, informing the Lincoln administration of Confederate activities in Canada. Ross devoted a substantial part of his book to his wartime service and testimonials from the leading abolitionist and antislavery figures, reproducing verbatim the Emancipation Proclamation and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address so beloved by abolitionists. At the end he added his thoughts on the controversies over Reconstruction, severely condemning the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. Such policies would leave black people “slaves in all but name,” he wrote. Southern whites were vicious, and could not be trusted to guarantee black rights. As he put it,

Anti-slavery and radical men demand that the freedmen of the South shall have the right of suffrage and complete equality before the laws, and maintain that the President has the constitutional power to guarantee these rights to the loyal coloured people of the States lately in insurrection.

Like most abolitionists, Ross rejected the politics of racial and sectional reconciliation that emerged after the fall of Reconstruction. Black and white abolitionist memoirs of the underground railroad remain an indispensable source for historians today, who have only recently revived its study after decades of abdicating the subject to lay writers.

Another popular sub-genre of abolitionist memoirs, often not counted as such, were slave narratives written and published in the aftermath of the Civil War. Around fifty-five such narratives saw the light of day only after the war, but they failed to replicate the success of their antebellum predecessors. Not only had antislavery fires cooled in the North, but abolitionists and African Americans also found the racist consensus that marked the post-war nation particularly unresponsive to their experiences. Even the most important of these—the third iteration of Frederick Douglass’ iconic autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, published in 1893—failed to garner the attention and acclaim that had greeted the first two versions. But, as in the earlier versions of Douglass’ narrative, his exceptional talents, life, and career, from slave to statesman, were summoned as an argument for the race. Black political leader and lawyer George Ruffin wrote in his introduction, “we bring forward Douglass, he cannot be matched.” Douglass illustrated the burden of being the representative exemplary black man: “I never rise to speak before an American audience without something of the feeling that my failure or success will bring blame or benefit to my whole race.” Douglass noted astutely that while his lecture on race was seldom in demand, his address on the self-made man suited the mood of the country better. More than any other abolitionist memoir, Douglass’ autobiography dwelled at considerable length on the plight of the freed people and the betrayals of Reconstruction. The freedman, he noted, was “turned loose, naked, hungry, and destitute to the open sky” facing the “bitterness and wrath” of his old master. He foresaw the problem of abandoning freed people to the tender mercies of their erstwhile masters:

Until it shall be safe to leave the lamb in the hold of the lion, the laborer in the power of the capitalist, the poor in the hands of the rich, it will not be safe to leave a newly emancipated people completely in the power of their former masters, especially when such masters have ceased to be such not from enlightened moral convictions but by irresistible force.

Black citizenship was the crowning achievement of the abolitionist project, and its overthrow produced precisely what Douglass feared: a nation that turned over the “colored” man, “naked,” to their “enemies.” Excoriating the Supreme Court decision “nullifying the Fourteenth Amendment,” he argued that the court, the nation, and the Republican Party had declared themselves on “the side of prejudice, proscription, and persecution.”

This was not a self-satisfied, conservative Douglass writing in his old age as a mere Republican functionary, as claimed by some scholars, but an activist who invoked the bygone lessons of abolitionism. As he acknowledged, “Forty years of my life have been given to the cause of my people, and if I had forty years more they should all be sacredly given to the same great cause. If I have done something for that cause, I am, after all, more a debtor to it than it is debtor to me.” Looking back at the abolitionist schisms, including his own memorable break with Garrison, Douglass viewed them as less consequential, though he did not paper over the differences. Despite his personal reconciliation with his master’s family and his post-war career as an office holder, Douglass remained an antislavery activist to the very end. While he had not supported the Kansas exodus, he wrote and spoke on behalf of Ida B. Wells’ anti-lynching campaign on the very eve of his death. Indeed, the dual purpose of redeeming abolitionist “honor” and contemporary activism marked all his last speeches and writings, brilliant eulogies on Garrison, Brown, Sumner, and Lincoln.

In fact, post-war black leaders played a pivotal role in the construction of abolitionist memory. Perhaps the most important of them was Archibald Grimke, who bore the name of his famous abolitionist aunts, and who would write the first biographies of Garrison and Sumner. His eulogy on Wendell Phillips in 1884 so enraptured surviving abolitionists such as Theodore Weld, Elizur Wright, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and Samuel Sewell that they insisted on having it published. In his introduction, Ruffin noted that while most did not appreciate Phillips, “colored people” did. He remembered Garrison and Phillips’ “words of wisdom and hope” in one of the last banquets held for them by black Bostonians. Grimke used his eulogy to provide a mini-history of abolition, without which, he contended, “our freedom would never have been born.” Lincoln obeyed the “public sentiment” created by abolitionists like Phillips. According to Grimke, the last period of abolition began in 1865 and “is not yet finished.”

Just as they had pioneered in marking British emancipation in their August First celebrations before the war, African Americans used antislavery funeral rites to commemorate lost allies and rekindle the flagging struggle for racial justice. They insisted on ritualistically commemorating the death of abolitionists such as Garrison, Phillips, and Sumner. Long after abolitionist reunions vanished from the scene, black activists continued to visit the grave of John Brown. At the start of the new century, the NAACP (probably at Grimke’s suggestion) commemorated the birth and death anniversaries of Garrison and Sumner. Through these commemorations, African Americans deployed abolitionist memory in their own struggles against racial inequality.

Many of those who sought to remember abolitionists and commemorate their legacy were descendants of abolitionists themselves. It is not surprising, then, to see the children of abolitionists play a significant role in compiling the archives of abolition and antislavery. These books were more than just exercises in filiopiety; they often combined painstaking historical research with collective memories of the movement. The most important of these was the multi-volume set on the life and times of Garrison put together by his sons, the committee of friends and family who wrote May’s memoir, and the biography of James Birney written by his son William Birney, who dedicated his book to students of American history. Radical Republican George Julian not only wrote his own recollections but also a biography of his father-in-law, the pioneering political abolitionist Joshua Giddings. Edward Pierce compiled the memoir and letters of his mentor Charles Sumner as a tribute after the latter’s death.

These books marked the transition from the proliferation of abolitionist memoirs to full-fledged efforts to write the history of slavery, abolition, and the war by the participants themselves. In 1886, when abolitionist Austin Willey published a history of antislavery in the nation and his home state of Maine, he still sought to use abolitionist memory as a way to jumpstart the waning struggle for racial equality. He dedicated his history to “the New Generations of American Citizens, of Whatever Race or Color, Who Can Know the Events Here Narrated only as History, But who must make the Events and History of the Future.” Willey noted that perhaps in the future, when “the disparagement with which the cause was loaded has passed away,” his work would supply “the common demands of memory in history.” He concluded with uncomfortable questions: “Freedom was given to the slaves, but did that settle the account? … Is our account settled?”

These works of abolitionist and antislavery history nonetheless incorporated memory and first-hand experiences that had marked the early abolitionist memoirs. In one of the first published works of abolitionist history, John F. Hume made a self-conscious effort to move from the terrain of memory to history in his The Abolitionists (1905). Written in response to Theodore Roosevelt’s denigration of the abolition movement, Hume, who professed to have been an abolitionist since “boyhood,” sought to insert “here and there a little history woven in among strands of memory like a woof in the warp.” The “personal experiences and recollections” of abolitionists, he pointed out, were scattered, and “by themselves would be of little consequence.” But when they carry “certain historical facts and inferences,” collectively they “are of profitable quality and abounding interest.” Joshua Giddings and Henry Wilson had earlier written the first systematic histories of the antislavery political struggle from the first-person perspective. Making no pretense of writing objective history, these antislavery histories nevertheless mark the origins of abolitionist historiography. Remarkably free from the triumphal tone of early nationalist historians, they were also less egregious in their biases than the generation of Southern historians and literary scholars who perpetuated the simplistic stereotype of the hypocritical, abolitionist fanatic and the pseudo-science of racial inferiority in the American academy at the turn of the century.

Long viewed as unreliable, vapid, apolitical, and self-congratulatory, works of abolitionist memory and history must be reconsidered as pointed critiques of the nation’s dismal failure to live up to the promise of emancipation after the fall of Reconstruction. They were akin to Albion Tourgee’s autobiographical novel, A Fool’s Errand, By One of the Fools (1879), which Tourgee bitingly dedicated “To the Honorable and Ancient Family of Fools […] By One of Their Number.” As one of the characters remarks at the end of the novel over the foolish northern carpetbagger’s grave, “There was a good foundation laid, and sometime it might be finished off; but not in my day, son, -not in my day.” Tourgee, a “latter-day abolitionist,” would continue the abolitionist fight against lynching, segregation, and disfranchisement long after it had become decidedly unfashionable. These “foolish” and radical abolitionist memories serve as an effective historical riposte to the nightmarish reality of racial injustice in post-Reconstruction America.

Like Tourgee’s novel on the tragic fall of Reconstruction, abolitionist memoirs of the time constructed an alternative history and memory of the past. As we mark the sesquicentennial of emancipation and the Civil War, abolitionists deserve to occupy a much larger place in our national memory and public commemorations. Some modern activists, like the abolitionists, sought to create an alternative memory of the fight against slavery to justify their struggles. For example, the Populists adopted the abolitionists’ lecturing agency system and the American Socialist Eugene Debs invoked their memory as radical dissenters. A black nationalist magazine in the 1960s adopted the name The Liberator. Civil rights activists dubbed themselves the “new abolitionists” and called for a Second Reconstruction. Even President Obama compared his “unlikely” victory in the 2008 Iowa presidential primaries to the story of the abolitionists.

But the recent sesquicentennial celebrations of emancipation and the Civil War have woefully neglected the abolitionists, divorcing their commemorations from the underlying abolitionist activism behind emancipation. We are in danger of replicating past commemorations of the Civil War that stressed sectional reconciliation and nation-building at the cost of forgetting the long history of abolitionist activism and the entrenched racial inequalities that abolitionists fought against. Perhaps it is more soothing to participate in a triumphal, national Whiggish narrative and forget those perennial abolitionist naysayers, staunch critics of the nation’s failure to fulfill the promise of emancipation and its subsequent betrayal of black freedom. The complex intersection between history, memory, and activism in post-war abolitionist writings and memoirs compel us to eschew simple narratives of progress as well as those which dismiss the importance of the abolitionists’ pioneering role in the coming of emancipation. The warnings that abolitionists sounded on descending into apathy and the lessons of activism they sought to instill are still very much with us today. Perhaps the best way to carry on that abolitionist legacy would be to spend less time on building monuments to past achievements and more on addressing contemporary racial inequalities, the fight they could rightfully claim to have inaugurated.

Further Reading:

For a sampling of post-war abolitionist writings see: Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I., 1891); Levi Coffin, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, The Reputed President of the Underground Railroad (Cincinnati, Ohio, 1898, Third Edition); Frederick Douglass, “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass Written By Himself” (Boston, 1893) in Autobiographies (New York, 1994); Archibald H. Grimke, A Eulogy on Wendell Phillips Delivered in Tremont Temple, Boston, April 9, 1884: Together with the Proceedings thereto, Letters etc. (Boston, 1884); Laura S. Haviland, A Woman’s Life Work: Labor and Experiences of Laura S. Haviland (Chicago, 1887); John F. Hume, The Abolitionists: Together with Personal Memories of the Struggle for Human Rights, 1830-1864 (New York, 1905); Oliver Johnson, William Lloyd Garrison and His Times: or, Sketches of the Anti-Slavery Movement in America, and of the Man who was its Founder and Moral Leader (Boston, 1879); Samuel J. May, Some Recollections of Our Antislavery Conflict (Boston, 1869); Parker Pillsbury, Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles (Concord, N.H., 1883); Sarah H. Southwick, Reminiscences of Early Anti-Slavery Days (Cambridge, Mass., 1893); Henry B. Stanton, Random Recollections (New York, 1887); William Still, The Underground Rail Road: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c … (Medford, N.J., 2005, reprint, Philadelphia, 1872); Albion Tourgee, A Fool’s Errand By One of the Fools (New York, 1879); Rev. Austin Willey, The History of the Antislavery Cause in State and Nation (Portland, Maine, 1879).

On abolitionism and memory see David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); Mark Elliot, Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgee and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessey v. Ferguson (New York, 2006); Julie Roy Jeffrey, Abolitionists Remember: Antislavery Autobiographies and the Unfinished Work of Emancipation (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2008); Margot Minardi, Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts (New York, 2010).

This article originally appeared in issue 14.2 (Winter, 2014).

Manisha Sinha is professor of Afro-American Studies and History at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is the author of The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina (2000) and The Slave’s Cause: Abolition and the Origins of American Democracy (Yale University Press, forthcoming 2014).