Collision of Interests

The Effie Afton, the Rock Island Bridge, and the making of America

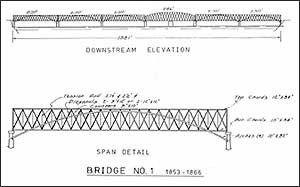

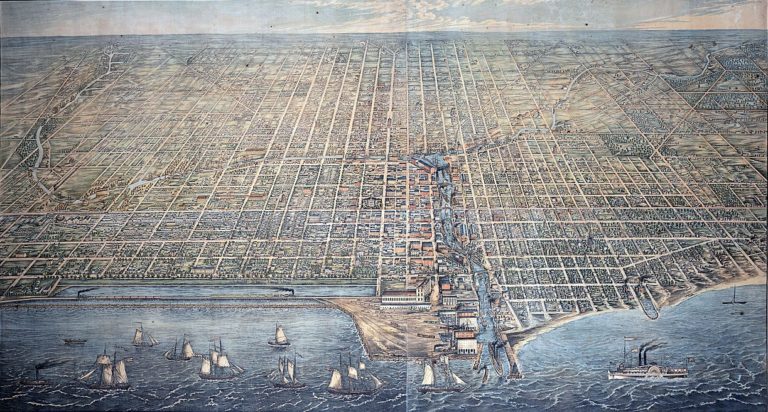

On April 1, 1856, engineers of the Railroad Bridge Company conducted a comprehensive examination of the just completed Rock Island Bridge. Built with more than two hundred and twenty thousand pounds of cast iron, four hundred thousand pounds of wrought iron, and one million feet of timber, the structure was the first railroad bridge to span the mighty Mississippi River. On April 21, confident in the integrity of the bridge but still exercising caution, company officials watched as a single locomotive, the Des Moines, rolled across the bridge from Rock Island, Illinois, to Davenport, Iowa. When three locomotives coupled to eight passenger cars completed the same short trip the following day, people standing along the tracks cheered and church bells rang out from both banks of the Mississippi.

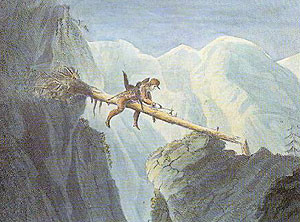

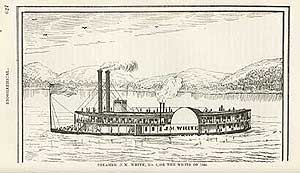

Just fifteen days later, on May 6, there was a celebration of a decidedly different nature between the two river towns. The late-model steamship Effie Afton, powering upriver through the draw of the Rock Island Bridge, collided with one and then another of the piers supporting the structure. The passengers and crew managed to escape harm, but the boat caught fire and was lost, as was its entire cargo. Before the incapacitated Effie Afton swung free of the bridge, drifted down river, and eventually sank, the long flames of the fire had reached the wooden trusses of the bridge. As the bridge began to burn, the other steamboats afloat on the river and tied up at Rock Island and Davenport blew their whistles in approval. When a section of the bridge collapsed, river captains, pilots, and crews cheered wildly. So loud was the scene that, as one newspaper reported, “it sounded like a vast menagerie of elephants and hippopotamuses howling with rage.” The Rock Island Bridge stirred up trouble in the waters of the Mississippi.

Boat destroyed and bridge damaged, the owners moved their conflict indoors, off the river and into the courtroom. Jacob S. Hurd, captain and co-owner of the Effie Afton, sued the Railroad Bridge Company. Alleging that the bridge was a material obstruction to the free navigation of the Mississippi River and therefore illegal, he and his fellow owners sought a judgment for “the value of the boat, her cargo, and such other damages as they may be entitled by law and the evidence to recover,” all of which they calculated to be sixty-five thousand dollars. The trial began sixteen months later in September 1857 in the United States Circuit Court in Chicago, with Supreme Court Justice John McLean presiding. The Chicago Daily Press informed its readers that it would surrender considerable space to covering “the celebrated Effie Afton case.” The editors explained that the trial was indicative of a fundamental national struggle in desperate need of resolution. In pressing their suit, the plaintiffs were defending the primacy of the navigable rivers, “the great natural channel of trade of the Mississippi Valley,” against the lengthening railroads, “the great artificial lines of travel and communication.” The editors believed that the conflict was “one of the most important ever to engage the attention of our courts.” Accordingly, they “made such arrangements as will enable us to lay before our readers . . . verbatim reports of all the more important portions of the arguments and evidence.”

Representing Hurd and his associates, Hezekiah M. Wead, Corydon Beckwith, and Timothy D. Lincoln professed a willingness to accommodate the growing railroad interests. In his closing statement Wead claimed “it was no part of [our] cause to prohibit the bridging of the Mississippi River.” He insisted that a bridge, properly designed and properly located, would pose no danger to river traffic. The Rock Island Railroad Bridge, he contended, however, was neither. Four and one-half years earlier, on January 17, 1853, the Illinois legislature had incorporated the Railroad Bridge Company “with the power to build, maintain and use a railroad bridge over the Mississippi River” between Rock Island and Davenport. The charter specified, though, that the bridge be erected “in such manner as shall not materially obstruct or interfere with the free navigation of said river.”‘

The Rock Island Bridge consisted of three sections, two of which were, in fact, distinct bridges. In the midst of the river between Rock Island and Davenport was an island—Rock Island—for which the Illinois town and the entire bridge structure were named. Moving east to west, the first section was a three-span bridge, 474 feet in length, connecting the city called Rock Island to the island called Rock Island. The middle section was the tracks across the island. Connecting the island to Davenport was the major section; this was the one at issue. It consisted of five 250-foot stationary spans and a 285-foot draw span. The draw span, which was the third span from the island and crossed over the main channel of the river, rotated atop a 386-foot-long turntable pier. The other piers supporting the main section of the bridge were significantly shorter: only 53 feet.

Whatever achievement the bridge represented in the field of engineering, Wead argued, the Railroad Bridge Company had built it in a manner uniquely suited to inhibit navigation. To begin with, the turntable pier was “placed laterally across the current of the stream.” This meant, according to the plaintiffs, that the water did “not run square under the draw.” Rather than directly “running between the long and the short pier,” water “strikes” the long pier, generating dangerous and unpredictable crosscurrents and eddies. Moreover, the Railroad Bridge Company located the bridge precisely where, in that stretch of river, the velocity of the current was greatest. The presence of Rock Island effectively narrowed the width of the river and increased the force of the stream. That condition was aggravated further by the addition of the bridge’s piers and by the ships themselves. The turbulent water, which made the draw virtually un-navigable, forced the Effie Afton into the bridge. In combination, the design and the location of the bridge qualified it as an unnatural, material obstruction to navigation on the river. Wead cast the Railroad Bridge Company as a “grasping corporation,” which placed the bridge where it pleased, disregarding navigation and disrespecting the public. More to the point, though, the Rock Island Bridge stood in violation of its charter.

Wead did not want the jury to trust him when he said Rock Island Bridge was an obstruction. He conceded that “obtaining accurate knowledge of the navigation of such a stream” was terribly difficult for “all men.” Referring to the specific circumstances that the Effie Afton faced, he said, “No man can tell what the difficulties of that navigation will be until he tries it.” “Without experience,” he believed, one really could not be “a competent judge” of such things. Accordingly, to help the jury fully comprehend the degree of obstruction to navigation, Wead turned to the men who made their living on the Mississippi River and its tributaries. They came from places like Galena and Savannah, Illinois, and from Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, and in addition to river boat captains, they included the highly esteemed river pilots.

By Justice McLean’s count, over fifty of these men testified that the design of the bridge “caused cross-currents and eddies in the draw,” which led to the “loss of the Effie Afton.” Witness after witness, pilot after pilot asserted that the bridge was an obstruction to navigation: “a material obstruction,” “a great obstruction,” “a serious obstruction,” “the worst obstruction on the Western waters.” Fifty-year-old Thomas Taylor had spent half his life as a pilot on the Mississippi. In his estimation the bridge was “a serious obstacle,” and he said to the person taking his deposition, “You may emphasize that as much as you please.” The pilots were equally adamant that the speed of the river increased dramatically in the draw. There was no consensus, though, on just how much faster the water was moving. Some estimated the current reached six miles per hour; others judged it to hit twelve miles an hour; one simply said the current was “a heap stronger at the bridge.” None had measured the speed of the current.

However fast the river, the pilots agreed, passing the bridge was “very unsafe.” William White, a river pilot between St. Louis and St. Paul for more than two decades, believed there was “a risk of life and property in going through the bridge.” He was not alone. David Moore “considered [passing the bridge] so dangerous that I took my money and other valuables on my person, to be ready for any trouble.” While Wead argued that only [river men] could truly appreciate the challenges of navigation, the pilots themselves noted that the danger posed by the bridge did not escape common passengers. Pittsburgh pilot George Neare recounted a story in which his passengers were so frightened at the prospect of passing through the draw of the Rock Island Bridge that they insisted on disembarking, walking around the bridge, and reboarding once—if—Neare safely guided the steamship to the other side. Moreover, he noted, marine insurance companies judged the bridge a significant risk: rates “have been greatly increased by the bridge.”

Wead aimed to win the legal case for Jacob Hurd and his associates on a narrow, technical point about river navigation. He sought to win the public relations case by situating the loss of the Effie Afton within a particular historical narrative about the father of the waters and the American nation. Wead reminded the jury that “the law is that the citizens of the United States have a right to the free navigation of the Mississippi River.” That had not always been true, though.

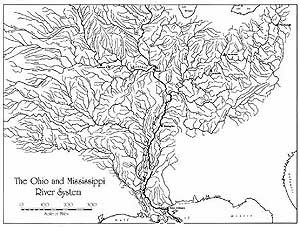

For Americans living west of the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi offered the only reasonable, economical way to deliver their surplus products to the markets of the world. In the two decades following the Revolutionary War, one of the most critical and troubling questions facing the emerging nation was thus whether Americans would enjoy the free navigation of the Mississippi River. Although the 1783 Peace of Paris established the western boundary of the United States at the middle of the channel, New Orleans and the mouth of the river fell under the control of the Spanish and then, briefly, of the French.

While European imperial powers could and did limit American use of the Mississippi through the 1780s and 1790s, western Americans regularly appealed to their Confederation and Federal governments for assistance. So vital did they consider easy access to the river that they even contemplated dissolving their political ties to the United States and pledging allegiance to whichever of the European powers would guarantee that access. In 1794 John Breckinridge of Kentucky explained to Samuel Hopkins of Virginia that while westerners were not yet prepared to form an alliance with the Spanish or even with the British, such a scenario was not inconceivable. He warned, “The Miss[issippi] we willhave. If Government will not procure it for us, we must procure it for ourselves. Whether that is to be done by sword or negotiation is yet to [be seen].” America’s jurisdiction over the Mississippi remained vulnerable until the British evacuated the Old Northwest following the War of 1812.

If Wead’s diplomatic history was somewhat weak, so too was his domestic political history. As he continued to make his case for the eternal and free-born American right to navigable waterways, he announced to the jury sitting in the Chicago courtroom that “care has always been taken to keep [the Mississippi] free from obstruction,” but he was overstating the case.

Although there were local efforts to improve sections of the rivers dating to before the Revolution and although a number of western states—Missouri, Minnesota, and Arkansas among them—called for state-level sponsorship of river-improvement projects in their original state constitutions, they ultimately did little to improve river navigation. On the national level, in February 1819, the United States Congress allocated sixty-five hundred dollars for “making a survey of the water courses tributary to and west of the Mississippi. Also, those tributary to and north and west of the Ohio.” The following year Congress provided “for making a survey, maps, and charts of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers from the rapids of the Ohio at Louisville to the Balize, for the purpose of facilitating and ascertaining the most practicable mode of improving the navigation of those rivers.”

Not until 1824, though, did Congress fund projects for the actual physical transformation of western rivers. Congress targeted six sandbars and the trees, “commonly called planters, sawyers, or snags,” that were fixed to the river beds and threatened to puncture the hulls of passing vessels. Perhaps the most important consequence of this legislation was the development in 1829 of Henry Shreve’s Heliopolis, the first snag boat. These boats, designed with a powerful crane set between double hulls could relatively easily remove deeply embedded trees weighing as much as seventy-five tons. Within just a few years snag boats removed most of the underwater forests of the Mississippi. By 1844 Congress devoted $2.5 million to various improvement projects, primarily on the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers. For the remainder of the antebellum period, though, funding was uneven; indeed there were stretches of several years when Congress made no appropriations for the general improvement of the western rivers.

Even though Wead bent his facts, he did not break them. There had been a long history—though not quite as long as Wead would have had the jury believe—of Americans upholding and defending the free navigation of the country’s main waterways. And, similarly, there was some history of the government funding “internal improvements,” such as the dredging of rivers. From these precedents, he explained to the jury, only one conclusion could be drawn: Americans prized the free navigation of their rivers above most anything. Wead could have added some potent voices to his case. In 1783, following the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, George Washington himself wrote that he was “struck with the immense diffusion and importance” of “the vast inland navigation of these United States.” As Washington contemplated the nation’s inland waterways, he was impressed by the “goodness of that Providence which has dealt her favors to us with so profuse a hand.” Washington hoped “to God” that Americans “may have the wisdom to improve them.”

If Americans had not always enjoyed free access to navigable waterways, some of them, at least, had always believed such access to be a right of citizenship and a requirement for union.

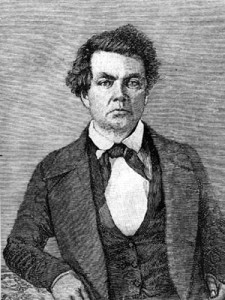

Representing Rock Island Bridge Company, Norman B. Judd, Joseph Knox, and Abraham Lincoln charged that opposing counsel Hezekiah Wead was “entirely mistaken in his statement of the facts,” and they proceeded to develop a multilayered defense. With detailed statistics of bridge passings, multiple scientific tests conducted by qualified engineers, and the observations of lay people living in the vicinity of the Rock Island Bridge, the counsel for the defense sought to dismantle Wead’s case by demonstrating that the bridge was not a material obstruction to the navigation of the Mississippi River.

Seth Gurney, among the first witnesses called by the defense, was the caretaker of the Rock Island Bridge and had been since April 19, 1856, two days before the steam locomotive Des Moines rolled across the bridge from Illinois to Iowa. Gurney stated that the bridge had been repaired by August 4, 1856, less than three months after the collision. He testified that he kept “a book in which by order I enter . . . every boat which passes.” According to Gurney’s log, in the thirteen months since the bridge had been repaired, “958 passages of boats have been made,” and only seven boats suffered damage. Referring to these figures and the river pilots’ insistence that the bridge constituted a dangerous obstruction, Knox said, “The pilots say that it is mere chance that they get through unhurt. Surely they are the luckiest men in the world.” He wondered, “Would not these boatmen soon amass a fortune if they could deal in lottery tickets?”

Defense counsel argued that the low number of accidents at Rock Island Bridge was not, in fact, due to the pilots’ luck. Nor did they offer that it might be the result of the same pilots’ well-developed skills. Rather, they argued there were few accidents because the bridge was well designed. To convince the jury of this, the defense called six engineers who had extensive experience with railroads, bridges, and rivers. Each of them visited the Rock Island Bridge and studied its construction and its effect upon the river. Each either conducted or observed tests of the direction, the predictability, and the speed of the current. They described the various tests they ran, most of which involved dropping weighted floats into the stream “some two hundred feet above the draw” and watching their movement as the current carried them down river through the draw. These tests, one engineer stated, were “regarded as a reliable means of determining currents in our profession.” The engineers agreed that there were no crosscurrents or eddies in the main channel and that the bridge was placed nearly as well as it could be. Knox acknowledged that the plaintiff’s counsel also “brought three engineers here” to add their testimony to the pilots’. Of the three, though, “only one ever saw Rock Island, and that was in February, when the river was frozen over.” None of the three conducted any tests on or even saw the effect of the bridge on the river.

To help the jury properly interpret their engineers’ tests, defense counsel called a number of local residents. John Deere, a fifty-three-year-old resident of Moline who was “engaged in the manufacture of plows,” witnessed some of the tests conducted by the defendant’s engineers. He described himself as “unskilled in navigation” and admitted that he had never passed through the bridge on a boat himself, but he still concluded that there were no crosscurrents in the main draw. Were there currents, he said, “the tests would have discovered them.” Patrick Greg, physician and mayor of Rock Island, testified that he had “watched floats pass in regular file down through the draw, never diverging to the left or the right.” He said, “The current according to my observation passes through the piers on the Rock Island side as smoothly and evenly as it is possible for water to run between piers.” Oliver P. Wharton was the “publisher of the Rock Island Advertiser,” and his “office window commands a view of the bridge and vicinity.” He had seen “floats in numbers,” “several hundred boats,” and “objects on the surface” pass through the draw “straight with the pier.” He said that he was “certain there are no cross-currents.” He thought “no difficulty whatever is offered by the bridge to the navigation of steamboats.”

Quincy McNeal, clerk of the Circuit Court of Rock Island, admitted, “From what had been told me I expected that there was difficulty until tests and experience proved to me that there is none whatever.” He had “seen the floats tried and pass through straight.” He concluded, “There are no cross currents in the draw.” McNeal said, “If a boat is left to drift from the opening of the chute she will go right through,” and David Barnes unintentionally demonstrated as much. Barnes was a resident of Rock Island and had been “engaged in the lumber trade for four years.” He recounted losing control of a raft, four hundred feet long and seventy-five feet wide—significantly larger than the Effie Afton—above the Rock Island Bridge in September 1856. He got caught in “the steamboat channel leading to the draw, and I could not get out of it to go to the usual place” where rafts passed the bridge. Barnes gave up and let the current carry the raft where it would. The raft “went straight down through the draw without touching.”

McNeal went so far as to say, “It is impossible for anything to get against those piers, except it be from some other influence than the current.” Defense counsel believed they could reasonably point to other influences. Judd charged that the fate of the Effie Afton was the consequence of no more than “the carelessness of her officers.” After all, immediately upon leaving Rock Island, the Effie Afton bumped into a steam ferryboat. From careless to reckless: with the bridge just three-fourths of a mile off, the Effie Afton engaged another steamer, the J. B. Carson, in a race to the draw, which affected the angle at which the Effie Afton approached the draw. Knox did not hesitate to attack the pilot Nathan Parker personally: although Parker may be in some respects “very excellent,” he was a “very timid man” with “delicate nerves.” He said that not until he listened to the plaintiff’s counsel had he “heard the praises of Mr. Parker as a tip-top pilot.” Knox asked the jury rhetorically, was Parker’s performance “not the height of unskillfulness?”

Although the defense alleged incompetence, they also suspected devious intent. The plaintiff had claimed that the fire that ultimately destroyed the Effie Afton and that damaged the bridge was the accidental consequence of a stove tipping over during the collision. But Judd argued the fire was no accident at all: “The fact is she got there where she would probably be lost and she had no insurance save against fire and some of them thinking it better to take half a loaf than nothing, set her on fire.” A physician who happened to be on the steamer Vienna the morning of May 6, 1856, testified that he witnessed Captain Hurd and a few members of the crew discussing the fact that the Effie Afton was only insured against fire. He believed that “one of them said: ‘It is a pity she don’t burn; she is good for nothing,’ and with an oath said: ‘I would burn her and get the insurance.’” Shortly thereafter the Effie Afton was burning out of control.

In his closing Knox cast the Railroad Bridge Company as “a little company” now under attack by the “the greatest river interest,” and he described the bridge not as an obstacle but as an “improvement” and one “which has benefited the whole land.” He moved the railroad into the position long held by the rivers. Abraham Lincoln followed Knox with a closing of his own and pushed the argument further. He said he had no desire “to have one of these great channels, extending almost from where it never freezes to where it never thaws, blocked up.” But the jury needed to see that Americans moved from east to west as well as north to south and that east-west travel “is growing larger and larger.” Between September 8, 1856, and August 8, 1857, Lincoln said, 12,586 freight cars and 74,179 passengers crossed over the Rock Island Bridge. Were it not for the Mississippi River’s “advantage in priority and legislation,” the railroad “would surpass it.” Navigation had been shut down for nearly four months the previous year when the river had been frozen. Moreover, Lincoln added, there is “a considerable portion of time when floating or thin ice makes the river useless, while the bridge is as useful as ever.” The artificial line was surpassing the natural channel, and speaking of the railroad, Lincoln said, “This current of travel has its rights” too.

The jury deadlocked at nine to three in favor of the bridge, so Jacob Hurd and his associates did not recover damages. After continued legal struggles, the final fate of the Rock Island Bridge was determined in January 1863 when the United States Supreme Court determined it could stand. By then, not a bridge but a war had stopped commercial traffic on the Mississippi River.

Further Reading:

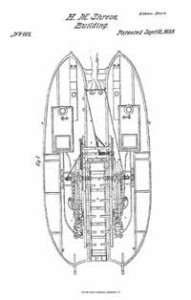

Reporter Robert Hitt covered the Rock Island Bridge trial and provided the transcriptions of the proceedings for the Chicago Daily Press. All trial quotations excerpted above appeared in the Chicago Daily Press, September 9-25, 1857. For more on the Rock Island Bridge, see Frank F. Fowle, “The Original Rock Island Bridge Across the Mississippi River,” in the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin 56 (1941): 55-63; Benedict K. Zobrist, “Steamboat Men versus Railroad Men: The First Bridging of the Mississippi River” in Missouri Historical Review 59:2 (January 1965): 159-172; and David A. Pfeiffer, “Bridging the Mississippi: The Railroads and Steamboats Clash at Rock Island Bridge” in Prologue Magazine 36:2 (Summer 2004). The image from William Riebe’s “Government Bridge” that appears above was taken from Pfeiffer’s article. For steamboats and river improvements, see Erik F. Haites, James Mak, and Gary M. Walton, Western River Transportation: The Era of Early Internal Development, 1810-1860 (Baltimore, 1975); Louis C. Hunter, Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History (Cambridge, 1949; New York, 1993). See also Michael Allen, Western Rivermen, 1763-1861: Ohio and Mississippi Boatmen and the Myth of the Alligator Horse (Baton Rouge, 1990); Stephen Aron, American Confluence: The Missouri Frontier from Borderland to Border State (Bloomington, Ind., 2006); Timothy R. Mahoney, River Towns of the Great West: The Structure of Provincial Urbanization in the West, 1820-1870 (Cambridge, 1990); Willard Price, The Amazing Mississippi (New York, 1963); and Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.4 (July, 2006).

Jenry Morsman is a stay-at-home dad, is ABD at the University of Virginia, and teaches occasionally at Middlebury College. He published “Securing America: Jefferson’s Fluid Plans for the Western Perimeter” in Douglas Seefeldt, Jeffrey L. Hantman, and Peter S. Onuf, eds., Across the Continent: Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and the Making of America (Charlottesville, 2005).