The Pathfinder’s Lost Instruments: John C. Frémont’s cavalier attitude toward his scientific apparatus

July 28, 1842, was a hot day along the North Platte River. John C. Frémont’s voyageurs raised the buffalo hide slightly around the bottom edge of his tipi when they pitched it, hoping to let a breeze blow through. Inside, Frémont’s cartographer, the phlegmatic Charles Preuss, started a fire under a pot of water while, outside, Frémont set up a tripod. From a leather case he withdrew a brass tube nearly a yard long, and hung it from the tripod’s apex. A small glass canister, about the size of a soup can, was attached to the bottom end of the tube. The bottom of the canister was made of leather, through which protruded the head of a screw that a person could loosen or tighten with thumb and forefinger. This was a cistern barometer, state of the art for its time.

The day was calm, and the instrument hung straight and still. It looked safe enough. To read what it had to tell him, Frémont would have put his hands on his knees and peered at a place near the top of the tube where the brass was cut away, revealing a glass tube cased inside. Inside the glass, the height of a column of mercury could be read on a measured scale. But first, he had to make some adjustments.

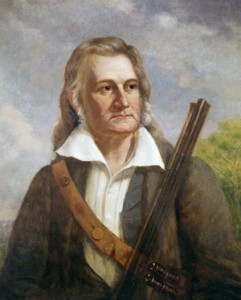

Frémont was twenty-nine, a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers, an intellectually elite, semi-autonomous branch of the U.S. Army in which he was one of only thirty-six officers. He was in command of two dozen men, on the first of five exploring expeditions he eventually would lead to the trans-Missouri West. He was a geographer, well trained in navigation and cartography, and benefiting professionally from some of the U.S. government’s earliest support of science. Though admirers would come to call him the Pathfinder, he was not an explorer; the route he was following in 1842 had been used regularly by white trappers and traders for two decades or more. He was, however, a popularizer, and the information he brought back would eventually open that route to hundreds of thousands. It became the Emigrant Road, the main trunk of the trails to Oregon, Utah, and California. But as much as anything, he was an adventurer.

Financing for the trip had been quietly engineered by Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, who also happened to be Frémont’s father-in-law. Benton had his eye on Oregon, which at the time meant all the country west of the Continental Divide and north of the forty-second parallel—now the northern border of California, Nevada, and Utah. South of that line, in 1842, was still Mexico. Oregon was claimed jointly by Britain and the United States; still, Benton wanted to see it filling up with U.S. settlers as soon as possible. Benton was a standard bearer for what came to be called Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was justly fated to fill the continent. Similar thinking led to the election of an expansionist president, James K. Polk, in 1844, and in 1846 Polk led the way to war with Mexico.

Benton had more immediate, tactical aims, however. Though much of the information on how to get to Oregon was sound, it was available only from word of mouth, and from a few maps that mixed fable and guesswork with fact. Frémont, Benton knew, would return with good information, and afterward the government could issue thousands of reliable maps. Then, given the right publicity, Benton could turn the politics over to a fast-growing, land-hungry public, and count on a reliable outcome.

Frémont and his men were now a month and a half out from the Missouri settlements and approaching Red Buttes near present-day Casper, in central Wyoming. Though his instructions from Colonel John Abert of the Topographical Corps were simply to travel up the North Platte to the mouth of the Sweetwater River, Frémont seems from the start to have planned to lead his men 150 miles beyond that point, into the mountains beyond South Pass on the Continental Divide. He had Benton’s tacit approval for this intention, and perhaps Abert’s as well.

A more extravagant disregard for instructions on his second expedition would lead him deep into California—still a part of Mexico—and would win him not censure, but fame. In California again in 1846 and ’47, he defied orders outright. By then it was wartime, however; he was court-martialed and left the army. His fourth expedition, a civilian attempt to cross the mountains of Colorado in the winter of 1847-48, ended in disaster and cannibalism among his men. His fifth, into Colorado and Utah, was of little consequence. His fame continued, however, and in 1856 he was drafted to run for president on the first national ticket of the Republican Party. But for now, near the North Platte, peering at the barometer, he was just curious. He wanted to know his elevation above sea level, and he planned soon to measure the true altitude of the Rocky Mountains.

Barometers measure the pressure of the column of air reaching upward into space, where there is no longer any air at all. The greater the observer’s elevation, the shorter and less dense the column of air above, and the less, therefore, it weighs. In Frémont’s time the connection between weather events and changes in local air pressure were not well understood; barometers were rare and used primarily to measure elevation. In this case, measuring the height of the mountains would mean getting the instrument safely to the top of a peak still 150 miles off. The men had left one barometer for safekeeping at the fur-trading post at Fort Laramie a week earlier. Since then, trail travel had broken another. This was the only one left, and Frémont, just now, was being careful with it.

Earlier in the day, the expedition had crossed the braided channels of the North Platte River and camped on the north side. The two dozen men were mostly French-speaking, civilian voyageurs from St. Louis, most mounted on mules and the others driving two-wheeled carts. They took the wheels and canvas covers off the carts and concealed them in dense brush in a cottonwood grove. In sand drifts nearby, they buried everything else they could do without for a few weeks, intending to pick it up on their return journey, and they named the place Cache Camp, because they hid so much equipment there. They would be traveling light now, carrying fewer provisions, and they would have to hunt more often. This was a risk; they had been warned that morning by a band of Oglalla Lakota after crossing the river that they soon would enter a landscape empty of buffalo and ravaged by drought and grasshoppers. But without the carts, they could leave the trail, perhaps find more game for themselves and grass for their animals, and locate mountains, canyons, lakes, and river courses they would otherwise have missed.

For locating topographical features, whether well known or little known, was at the core of what Frémont had been sent out to do. Locating them meant pinpointing their latitude, longitude, and sometimes their elevation, raw material for the good maps Benton demanded. Frémont had trained in field observation and mapmaking with one of the best, the French-born geographer Joseph Nicollet, whom Frémont had accompanied on earlier expeditions to the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Now in charge of his own expedition, he had brought along the German-born cartographer Charles Preuss. Preuss and Frémont both kept daily journals. Frémont’s formed the basis for his first report, published the following spring. Preuss’s remained unknown to scholars until the 1950s. Both are in print today, provide lively reading and a useful contrast to each other, and are the main sources for this account. Preuss also made landscape sketches, engravings of which accompanied Frémont’s reports.

The scientific instruments were “good instruments,” Frémont notes in the report, with uncharacteristic understatement. They were in fact state of the art for the time; given the need for portability, they were the most accurate available. As such, it is not too much to see them as emblems of the nation’s newly institutionalized support, by way of Congress and the Topographical Corps, for science—especially when the science served national expansion.

Besides their journals, Frémont and Preuss kept logs of their instrument readings. They took readings at river confluences, important landmarks, most campsites, and many noon halts until, as we shall see, some of the instruments fell prey to accident. Frémont’s alternating care and carelessness toward them was bound up with the cavalier adventurousness that was so much a part of his character. But it seems fair, too, to connect his attitude with a larger national recklessness at the heart of Manifest Destiny.

To measure latitude, Frémont had two sextants and a reflecting circle, essentially sophisticated protractors; they were used to measure the angle of the sun or the polestar above the horizon. But among trees or in the mountains, the horizon was impossible to locate, and so Frémont also carried with him a couple of so-called artificial horizons. These flat boxes, filled with a shallow puddle of mercury, provided a level, still, bright-silver surface in which the heavenly object would be clearly reflected. The geographer could use his reflecting circle to measure the apparent angle between the heavenly object and its reflection and divide the result by two, thus doubling the accuracy of his measurement.

Measuring longitude was trickier. Ancient geographers divided the round earth into 360 degrees of longitude, which correspond nicely with a twenty-four-hour day. That is, fifteen degrees of longitude correspond to one hour, or one twenty-fourth, of the globe’s daily rotation. If only you had a clock reliable enough to keep telling you the time at a distant, fixed spot on the globe, you could, by noting the time difference between when that clock said noon and when it actually was noon where you were—when the sun was as high in its arc as it was going to get that day—you would know the number of degrees you were east or west of the fixed spot on the globe. By Frémont’s time, the fixed spot had been established for 150 years in Greenwich, England. Spring-driven clocks that would keep reliable time on board ship or on a long journey overland—chronometers, they are called—had been available for about sixty years.

At first, chronometers were expensive and rare; Lewis and Clark did not have one. By 1842, Frémont felt able to afford three. These were a ship’s chronometer—a big one in a box, suspended with gimbals like a ship’s compass—and two smaller, sturdier, pocket-sized ones. The big one would have been the most reliable had they been at sea, but it did poorly on the trail. They left it and one other behind at Fort Laramie. They took the best chronometer with them but it, too, did not keep perfect time.

For that reason it was standard practice to use a backup system of astronomical observations involving the moons of Jupiter. The observations required a powerful telescope; Frémont’s was 120 power, fifteen times as strong as a pair of modern binoculars. The observations also demanded good weather, a lot of math, a time of the month when Jupiter was in the sky, and lengthy nighttime observations. The clocks, of course, could be read at a glance and worked about the same night or day in all weather. But they were fragile. If they were dropped, or if they got wet, a person was out of luck.

At Cache Camp, where they hid the carts, Frémont’s astronomical and chronometric observations worked out to a longitude of 106 degrees, 38 minutes, 26 seconds west of the Greenwich meridian, and a latitude of 42 degrees, 50 minutes, 53 seconds north of the Equator. This is not bad; as might be expected, it is better in its latitude than in its longitude. A modern GPS device at the spot just across the Platte River from present-day Casper, Wyoming, where he may have camped, puts his readings within about two minutes of the real latitude, but shows his longitude was eighteen or nineteen minutes off.

That still left the matter of elevations, which is what both Frémont and Preuss were trying to measure once the tipi was pitched that July afternoon. While Frémont unpacked and hung the barometer, Preuss, seeking a second opinion, started the fire. Water boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit at sea level, and boils at lower temperatures—because of the lower air pressure—at higher elevations. The difference between the temperatures gives an indication of the actual elevation. But as with the chronometers, the expedition was having trouble keeping the thermometers safe from damage. Already they were down to just one with a scale that went high enough to measure water’s boiling point. The men had already broken their best thermometer. The one Preuss was using inside the tipi had a scale high enough to measure water’s boiling point, but it was too small to allow for graduations of much accuracy.

In any case, it is possible to imagine the tall, red-faced Preuss, thermometer in hand, watching closely as the water came to a boil, and slight, dark-eyed Frémont adjusting the screw on the bottom of the transparent, soup-can-sized canister—the cistern on the bottom of the barometer where it hung from the tripod. By turning the screw he could bring the level of mercury inside the glass beaker up just high enough to touch the point of an ivory pin set there to mark zero on the scale, allowing, each time, an accurate reading at the top.

Perhaps Preuss said something from inside the tipi about the water starting to boil. Perhaps Frémont, intent on his work just outside, answered him absently. Suddenly, as if out of nowhere, a gust of wind slammed the lodge and blew it over—Preuss, fire, water pot and all, along with, Frémont wrote later, “about a dozen men, who had attempted to keep it from being carried away.” In the confusion Frémont managed to save the barometer, “which the lodge was carrying away with itself,” but the thermometer broke. They had no others that would measure above 135 degrees, so from now on, elevation data would depend on the barometer alone.

The tipi blew over through no fault of its own, however. It was a good-sized lodge, eighteen feet across and twenty feet high, of that superb conical design which keeps a person warm in winter, cool and mosquito-free in summer. Frémont had acquired it at Fort Laramie, probably from the Lakota camped there. At the fort Frémont also had hired an interpreter, a trader named Joseph Bissonette, and also had agreed at the request of some of the Lakota headmen to allow a young Lakota man and his wife to come along. When Frémont’s men had tried to set up the tipi the first night out from Fort Laramie, the woman had laughed at their clumsiness and since then had often helped—probably supervised—setting it up every evening. Pitching and striking tipis was women’s work, and the Lakota women were quick about it.

But Bissonette had agreed to accompany the expedition only as far as Red Buttes, now just a few miles away. That afternoon at Cache Camp, he and the Indians would have been preparing to leave, and so the voyageurs must have set up the tipi on their own for the first time. They had done a poor job.

As the tipi toppled, and the men struggled with poles and flapping lodgeskins, Frémont would have unhooked the barometer from its tripod and then tilted it very carefully to allow the mercury to flow slowly to the top of the tube, preserving the vacuum inside the tube and allowing for accurate pressure readings in the future. Next he would have had to screw up the screw at the bottom of the cistern, sealing the leather against the bottom of the tube and sealing the mercury into the column. It would have been a delicate moment, among the wind gusts. If the instrument were tilted too fast, the mercury could slam into the top end of the tube and break it. If the bottom were not securely sealed, the mercury could slosh and air would get into the tube, ruining the vacuum. Then, very carefully, the barometer would be slid back into its leather case and slung from a strap over the geographer’s shoulder, upside down with the cistern at the top, ensuring that the mercury filled the tube and the vacuum stayed safely protected.

At this point, the river fishhooked south, while the trail struck out southwest across country. Geographer that he was, Frémont chose to follow the Platte instead of the trail. They headed south, upriver past Red Buttes, and camped at a grassy spot a few miles above the mouth of what is now called Bates Creek. Another day’s journey brought them to Goat Island, which they named for bighorn sheep they found there and killed. The island lay a short distance downstream from a narrows they named Hot Spring Gate, where the Platte cut through a ridge between high walls near a hot spring. Upstream from there, canyon walls closed in completely, and so the next day the men left the river, climbed over steep, barren hills, and fifteen miles later descended more gradually back down to the Sweetwater, flowing in from the west. Turning right, up the Sweetwater, they headed for the Continental Divide.

Frémont reported the Sweetwater sixty feet across, twelve to eighteen inches deep, flowing moderately—much the same as a person would find it now, at the end of a modern July. But then, buffalo grazed near the river. The men camped in a cold rain, and the hunters killed some cows; the next day they moved seven miles further up to camp a mile below Independence Rock. Here they rejoined the trail. They spent two nights, the hunters killed more buffalo, and everyone pitched in to cut the meat in strips and hang it on racks in the sun to dry. An extra day by the stream must have been a welcome respite from traveling.

By now it was August, and the weather was changing as they steadily gained altitude. Six miles above Independence Rock, they came to Devil’s Gate, where the normally placid Sweetwater cuts a dramatic, V-shaped notch through a granite spur out of the hills nearby. Again it rained. No one had any tents; they seem to have left them behind with the carts. Some nights, big sagebrush was their only shelter. There were no trees along the river, but driftwood lay scattered along its banks. With this, and what the voyageurs called bois de vache—buffalo chips—they made fires.

A day and a half beyond Devil’s Gate they got their first view of the Wind River Mountains, looking low and dark; these marked the Continental Divide and beyond them lay Oregon. On up the Sweetwater they progressed, timbered mountains miles off on their left, bare-granite rocks rising close and steep on their right. They passed buffalo, antelope, spied the only grizzly bear of the trip, found an abandoned dog and a sore-footed horse, and now and then unpacked their instruments to take more readings.

Towards the head of the valley, they came to the place where the Sweetwater, now a rocky creek, foamed out of a canyon in “wildness and disorder,” Frémont wrote later. The route got steeper and the trail again left the river for easier going. As he had on the Platte, Frémont stayed with the river. They found traces of old beaver dams, falling apart now as the beaver trade had killed off all their tenants. Finally the rock walls came too close. The men followed a ravine up to a high prairie and camped by a tributary. Here, Indians had left some poles, and so Frémont, Preuss, and some of the men were able to spend a night in the tipi, which they had brought along. The next night, just a few miles from South Pass and the Continental Divide, they again took longitude and latitude, but, for some reason, no barometer readings for altitude.

Instead, Frémont estimated the pass’s elevation at seven thousand feet—not bad, though his calculation the following year of 7,490 was far better. The place is broad, flat, and undistinguished, and so dry and windy that people seldom linger. The men had come 120 miles from the mouth of the Sweetwater, Frémont reported, 320 miles from Fort Laramie, 950 miles from the settlements on the Missouri. Now they were far beyond the extent of Frémont’s written instructions. Crossing South Pass, they were leaving the drainage of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. They were leaving the United States and entering Oregon.

Frémont now led the party northwest up the west side—the Oregon side—of the Wind Rivers. Off the established trail now, he relied more heavily on the wilderness skills of his best men: Kit Carson, a Taos-based former fur trapper whom Frémont’s reports would make famous, and the most competent of the St. Louis-based voyageurs: Basil Lajeunesse and Clément Lambert. From the west side the mountains rose more steeply from the plains at their feet and appeared more dramatic than they had on the long approach from the east. Frémont admitted they were beginning to appeal to his ideas of alpine beauty, though Preuss, German by birth, remained skeptical. Soon they turned their mules east and headed into the mountains. More than anything, it seems—certainly more than he wanted to follow orders—Frémont wanted to know how tall these mountains were.

And then, near the end of a day, they crossed the outlet of a lake. The stream was wide, swift, deep, and cold, and the rocks were sharp. The mule carrying the barometer must have slipped; perhaps it fell. In any case, the barometer broke—a “great misfortune,” Frémont reported later in his published report. The entire party supposedly felt the loss. Trappers, travelers, hunters, and traders had been arguing so long about the mountains’ true height that “all had looked forward with pleasure to the moment when the instrument, which they believed to be true as the sun, should stand upon their summits, and decide their disputes.” They camped on the north shore of the narrow lake. Frémont took latitude and longitude readings, took compass bearings to the various mountain peaks, and settled in to fix the barometer.

The main tube was still intact, but the glass cistern had broken. To replace it, he tried to cut the bottom out of an extra glass beaker. But he had only a rough file to cut with and the beaker broke, as did two more. Then he stored the barometer for the night in a groove the men had cut in a tree trunk, and in the morning he began again. He commandeered a powder horn from one of the men. The powder horn was worn thin by years of use and nearly transparent. Frémont boiled it to make it soft and workable, scraped it thinner for greater transparency, stretched it on a piece of wood to exactly the diameter he needed, bound it to the bottom of the instrument with stout thread, and glued it snug with buffalo glue. A piece of leather that had served as a cover for one of the glass beakers made a good adjustable pocket for the bottom of the powder horn-cistern. He next took mercury from one of his artificial horizons, heated it to drive off any excess moisture, and filled the cistern with the bright, heavy, liquid metal. Then he left the instrument upside down for several hours while the glue dried. Finally came the moment of truth. Carefully, he turned the barometer right side up. Everything held, nothing leaked, the vacuum stayed intact.

Time to climb the mountain. Leaving eleven men and twenty or so mules in a little fort-corral they built by the lake, the other fourteen men took fifteen of the best mules, and headed out.

The climb eventually cost them six days and five nights, and a sharp quarrel between Carson and Frémont. Eventually it was Lajeunesse, not Carson, who found the route up. Six men made it to the summit: Frémont, Preuss, Lajeunesse, Lambert, a voyageur named Descoteaux, and Auguste Janisse, called by the men Johnny, a mulatto and the only African-American in the group. Descoteaux and Lambert at one point extended a ramrod from above to help the others over a steep, slick slab. Janisse carried the barometer.

At the top, large enough for only one person to stand at a time, they unfurled an American flag, fired off pistols, and cheered. Then someone set up the tripod and hung the precious barometer. Preuss took two readings; later computations produced an estimated altitude of 13,570 feet, only 160 feet below the true height of the mountain, subsequently named Frémont Peak. Frémont was elated, and convinced (incorrectly) that he had climbed the highest peak of the Rocky Mountains. Preuss was, as usual, less impressed. “As on the entire journey,” he wrote later, “Frémont allowed me only a few minutes for my work. When the time comes for me to make my map in Washington, he will more than regret this unwise haste. After about fifteen minutes we started on our return trip.”

The barometer broke for a final time on the last afternoon of their march out of the mountains, before they had even returned to their camp by the lake. Frémont was chagrined, as he had hoped to be able to compare the instrument’s readings with those of another scientist’s barometer back in St. Louis, for a better read on his accuracy. He does not say whether he decided to leave his broken barometer behind. His other instruments still worked fine—sextants, reflecting circle, artificial horizon, telescope, chronometer, several compasses and probably a couple of thermometers—and he continued recording latitudes and longitudes.

On August 22, they again reached Independence Rock on the Sweetwater. Hoping for the best, Frémont unpacked yet another piece of remarkable equipment—an India rubber boat. It was twenty feet long and five wide, Frémont tells us, and appears to have had separate compartments, each inflatable with a bellows. He had ordered it the previous March, and it was delivered a few weeks later to the household of Senator Benton, in Washington, where Frémont lived with Jessie Benton Frémont, his bride of a few months. Its maker, Horace Day of New York, uncrated it on a broad gallery that opened off the Benton dining room, apparently for the admiration of friends and family, warning everyone as he did so that the new rubber might give off a strong odor. This proved to be the case. It was so bad everyone at the party had to leave, and the boat—still uninflated, apparently—was hustled out to the barn. To fumigate the house, servants hustled among the rooms and hallways, carrying ground coffee on hot shovels to cut the stench with something more pleasant. Sixty years later, Jessie told her biographer that though she barely remembered the boat, she clearly recalled its smell; she was newly pregnant at the time and the odor brought on an enormous nausea.

Frémont says he brought the boat along specifically to survey the Platte, but its purchase really shows his affection for everything newfangled. The men had used it first to cross the unexpectedly swollen Kansas River in early June. With the resourceful Basil Lajeunesse swimming out ahead, bow rope in his teeth, until he reached the far shore, it had worked fine on six cart-ferrying trips. But in his haste, with dark approaching, Frémont had the men load two carts on for the last trip, and the boat capsized. They lost a lot of sugar and nearly all the coffee, and two men nearly drowned. Frémont blamed the man who was steering the boat for being “timid on the water.” A wiser leader might have learned not to risk lives in haste.

Now Frémont was eager to try the boat again—and this time for a voyage, not just a crossing. Remarkably, they tried to launch at Independence Rock, still nine miles upstream from the Sweetwater’s mouth. But, packed with gear and four or five men, the boat drew too much water. They dragged it for two miles along the river’s sand- and pebble-bottomed meanders before giving up, deflating it, waiting for the rest of the party to arrive, repacking boat and gear onto the mules, and heading down along the south bank—again, with no trail—toward the Platte. They had to scramble up over some big rocks before coming down finally to a small, open place near where the Sweetwater rushed into a turbid Platte, running swollen and smooth. They camped for the night. From this distance, they could not yet hear the roar of rapids below.

Next morning they started before sunrise, expecting to reach Goat Island, thirteen or fourteen river miles away, for breakfast. Seven men climbed aboard—Frémont, Preuss, Lambert, Lajeunesse, Descoteaux, and two more voyageurs, Honoré Ayot and Leonard Benoît. The boat had already been loaded with all the instruments, with their trail journals, their notebooks of data, their guns, personal baggage, and food for ten days.

“In short,” Preuss wrote, “since we now live separate from ‘the common crowd,’ all the good things were retained for us”—sugar, chocolate, macaroni, the best meat of three recently killed buffalo cows and some recently smoked buffalo sausage—”and only the ordinary left for the others.” The rest of the men and all the mules were dispatched overland, under the leadership of Baptiste Bernier, another of the voyageur-lieutenants. Frémont may have taken far more food than they needed on the boat with the intention of easing the mules’ burdens, floating all the way to Fort Laramie and letting the others pick up the carts at Cache Camp. But the fact that they also took the best food, that Carson was not put in charge of the overland contingent, and that Preuss hints at some kind of rift also may reveal that Frémont and Carson had not patched up their earlier quarrel.

Frémont’s motives are unclear. He made a career of rash decisions; this was the first notorious one. Perhaps he was so eager to know what his new rubber boat could do that he did not think of much else. He had a keen mind for mathematics, for cartography, and geography, and understood thoroughly all the processes of measurement that would get him the best data possible. At the same time he risked the notebooks that contained all the information he had gathered so far—and worse, he risked his men’s lives. “We paddled down the river rapidly,” he reported later, “for our little craft was as light as a duck on the water.”

The sun was well up when they came to the river’s first cut through a ridge. They stopped on a point on the right, just inside the first steep curve where the river was starting to move fast. They got out, scrambled up the ridge for a better look, and saw rapids but no falls that looked too large to navigate. Looking at the broken ridges around them Frémont was sure it would have been too much trouble to carry the boat and all their stuff around the fast water, “and I determined to run the cañon,” he wrote. It was narrow and high; back down at the water level they saw where big logs from spring floods lay stranded on walls twenty or thirty feet above their heads. Preuss pocketed the chronometer and clutched his notebook. They made it safely through three rapids in quick succession, emerged into an open place where the river slowed and, exhilarated, pulled over for breakfast—some of that good sausage and a swallow of brandy.

After an hour they embarked again. Twenty minutes of smooth water brought them to a much larger, darker canyon, ominous in its height. They stopped again, Frémont wrote, and climbed to a spot where they could see the river winding seven or eight miles through walls two- to three-hundred feet high on the near end, five-hundred feet high farther down. These vertical distances are about right, but there is no view of the entire canyon from the hill they most likely climbed, or from anywhere near the canyon’s upper entrance. Though both men noted they were now bold from their earlier success, Preuss noted specifically that they did not reconnoiter. Hoping to protect the chronometer, he got out to walk the shore, but soon found the shore gone and rock walls running straight into the water. Meanwhile, the other men tried lining the boat; Lajeunesse and two others got out and walked the shore, holding one end of a fifty-foot rope attached to the stern. Then the boat stuck between two rocks. Water swept over the sides and began carrying away a sextant and a pair of saddlebags; Frémont grabbed the sextant but the saddlebags flowed away. Next, the boat unstuck and came up to where Preuss was standing. With the chronometer in a bag around his neck, he climbed aboard—the roar of the water now deafening—while the men with the rope made it to a big rock twelve feet above the level of the river. But the force of the water proved too great. Two of the men let go. Lajeunesse kept holding, and the line jerked him headfirst into the water. The boat shot on and, remarkably, he appeared again behind them in the current, disappeared, reappeared, his head a black speck in the white, white foam.

At last they turned the boat into an eddy. Lajeunesse caught up, swearing he had swum half a mile. All three rope men climbed aboard yet again. Everyone knelt now in the boat, took up a short paddle, and on they went, finally so exhilarated they shouted “hurrah” as Preuss has it, or, as Frémont has it, were just reaching the chorus of a Canadian boat song when the boat careened down a fall, struck a hidden rock, and flipped. Frémont and Preuss found themselves on the left-hand shore, the other men with the turtled boat on the right. Lambert was holding Descoteaux, who could not swim, by the hair. “Lâche pas,”cried Descoteaux, “lâche pas, cher frère.”—Don’t let go, brother! “Crains pas,” came the reply, “Je m’en vais mourir avant de te lâcher.” —Fear not! I’ll die before I let go of you!

At least, that is how Frémont wrote the story. Lajeunesse, meanwhile, righted the boat and with one or two of the others, managed to paddle some ways farther before a rock tore a hole in a second compartment and the boat slowly deflated into uselessness. There is only one route by which any of them could have climbed the four or five hundred feet up out of the canyon, and it leads up from the west, that is, left-hand side of the river. Frémont and Preuss appear to have taken this; how the others made it out is less clear. Preuss managed to hang on to the chronometer, but the water had stopped it. He also saved his detailed, melancholic diary—which did not turn up for more than a century, and which provides such a valuable anchor to Frémont’s buoyant optimism.

It was a long, hungry walk to Goat Island. Frémont had lost one moccasin and had to pick his way among rocks and cactus on one sock foot. After several more miles the canyon ended; then it was another five miles along braided river meanders now drowned under Alcova Reservoir. Then Hot Spring Gate, where Alcova Dam now lies, a final scramble over a sharp, red-rock ridge, and finally, below them, they saw Goat Island, waved to their friends, and smelled buffalo ribs roasting on the fire. That night it rained, but they slept right through it. Early next morning, Frémont sent the tireless Lajeunesse and a mule or two back to the canyon to recover whatever he could. They made Cache Camp the following day, exhumed the stuff and re-rigged the carts, and camped the following night at the ford on the Platte.

When they finally sorted everything out, they had lost many of the notebooks, though not all. Descoteaux had happened to have Frémont’s double-barreled rifle between his legs when the boat flipped and so it, too, was saved. Most of the scientific instruments were lost: the sextants, the big telescope, the five compasses, the artificial horizons; even the thermometers. The chronometer was ruined, and the one they had left at Fort Laramie ran poorly, so Frémont got no more reliable longitudes for the rest of the trip. He did save the reflecting circle, so he kept measuring his latitudes.

That winter Frémont wrote his report, or rather, dictated it to Jessie, who almost certainly added color and pace to the account. The document, including a detailed map of the corridor the expedition had traveled from the Missouri River to South Pass, was delivered to the Senate in March, 1843. The Senate immediately ordered one thousand copies printed for sale to the general public. Benton’s propaganda plans were working; that summer saw the first really large emigrant party—a thousand people—heading out for Oregon. Frémont, too, set out again. His orders were to travel to Oregon and come back the same way. But he followed his own wishes and took a much longer side trip, this time to California. A near-suicidal crossing of the Sierras in midwinter cost him the lives of two of his men. It also made clear to him and Preuss the nature and existence of the Great Basin, that enormous, counterintuitive sink east of the Sierras and west of the Green and Colorado drainages, where rivers flow out of mountains and simply disappear. When, in 1845 and 1846 Frémont traveled again to California to—accidentally on purpose—get the California end of the Mexican War started, Preuss stayed behind in Washington to keep working on the maps.

And in the shadow of America’s and Frémont’s reckless imperialism in those years, of Frémont’s growing incompetence and despair, and finally in our pity for his obscure decline and poverty-ridden death, it is easy to forget those maps. They are wonderful. The Senate published the first in 1845. It covers most of the trans-Missouri West, but Frémont and Preuss, to their great credit, mapped, with one or two exceptions, only the places they had seen. Good scientists, unwilling to vouch for what they did not know for sure, they left the rest blank. In 1846, the government published their seven-part map of the road from the mouth of the Kansas on the Missouri to the mouth of the Walla Walla on the Columbia. Tens of thousands were published. No one needed a Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, or Tom Fitzpatrick any longer to lead the wagons over plains and deserts. You had only to follow the map—with landmarks, water sources, and dates keyed to the descriptions in Frémont’s reports—all at an easy-to-read ten miles to the inch.

“War – Ground of Snake and Sioux Indians,” it says, in capitals that curve two hundred elegant miles from the Green River to the hills north of Red Buttes. True. “Ridges and masses of naked Granite destitude [sic] of vegetation,” it says in smaller letters the length of the Sweetwater Rocks, just north of the Sweetwater River. Also true. Under “Remarks” in the lower left-hand corner it lists “Fuel,” then adds, “Cotton wood and willow sufficient near the water courses and sage (artemisia) all over the country . . . often as high as the head . . . sometimes eight feet high, and several inches in diameter in the stalk. Makes a quick fire.” True again. “Game. At Sweetwater River buffalo appear for the last time, and emigrants should provide themselves well with dryed meat. West of that region nothing but a few deer and antelope, very wild, are to be met with.” True, though within a year or two, buffalo would be scarce on the Sweetwater too. “Water,” it reads. “Abundant.” True, if a traveler kept close to the rivers. Otherwise, false, false, false.

When he got back to Washington, Frémont made Jessie a present of the flag flown from the top of the peak, unfurling it across their bed. The report in its various best-selling editions contained any of several illustrations of the Pathfinder on top of the mountain, hand on the pole, flag whipping in the wind while the other men gaze up admiringly from below.

But an equally true picture would have shown Preuss on the peak, hands on his knees, notebook under his armpit and pencil behind his ear, peering through the wind at the top end of the barometer while Janisse or Lajeunesse steadied one of the tripod legs. From below, Frémont, already headed downward, shouts back over his shoulder for them to hurry up, get a move on; one reading of the barometer was good enough. His haste, his well-equipped sloppiness, may have been the most American thing about him. They had a continent to conquer, and time was getting short.

Further Reading:

The first book I read on Frémont was Edward D. Harris’s compact John Charles Frémont and the Great Western Reconnaissance (New York, 1990), aimed at the young adult market but still a good short introduction to the subject, packed with maps, portraits, and nineteenth-century illustrations. Web browsers will enjoy Bob Graham’s delightfully sprawling Website on Frémont, his science, and a wagonload of related topics. It was here that I first found pictures and detailed descriptions of Frémont’s instruments, and Graham helped me a great deal with this essay, responding clearly and patiently to my emailed questions.

Map lovers can find a copy of Frémont’s and Preuss’s seven-part map of the route to Oregon by going to the Library of Congress’s American Memory Website and then typing “Topographical Map of the Road from Missouri to Oregon” into the search window. Red Buttes, the Sweetwater Valley, and the Wind River Mountains are on map 4.

Ferol Egan’s thorough Frémont: Explorer for a Restless Nation (Garden City, N.Y., 1977), was probably the most useful biography overall; Tom Chaffin’s more recent Pathfinder: John Charles Frémont and the Course of American Empire (New York, 2002) serves a similar purpose. The first modern Frémont biography was Allan Nevins’s adulatory Frémont: Pathmaker of the West 2 vols. (New York, 1961), published in earlier versions in 1928, 1939, and 1955. And William H. Goetzmann’s excellent Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863 (New Haven, 1959) gives a detailed account of Frémont’s scientific apprenticeship on the upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers with the French geographer Joseph Nicollet.

Readers of any or all of these positive accounts would do well to temper them with David Roberts’ A Newer World: John C. Frémont, Kit Carson and the Claiming of the American West (New York, 2000), which tells in detail the story of Frémont’s disastrous fourth expedition of 1847-48, when he abandoned his snowbound men to starve in the Colorado Rockies, and some resorted to cannibalism to survive.

Lovers of primary sources will enjoy reading Frémont’s ebullient account of the 1842 expedition side by side with Preuss’s skeptical one. Frémont’s is available in paperback as The Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, with an introduction by Herman J. Viola and Ralph E. Ehrenberg (Washington, D.C., 1988). A reprint of Frémont’s first bestseller, it contains his reports both of the 1842 expedition and the 1843-44 expedition.

Preuss’s diary, which he kept in German, did not turn up until the 1950s, and was published in translation in the U.S. as Exploring with Frémont: The Private Diaries of Charles Preuss, Cartographer for John C. Frémont on his First, Second and Fourth Expeditions to the Far West, trans. and ed. by Erwin G. and Elisabeth K. Gudde (Norman, Ok., 1958).

Other editions of Frémont’s reports include at least one available online, The Life of Col. John Charles Frémont, and His Narrative of Explorations and Adventures, in Kansas, Nebraska, Oregon and California. The Memoir by Samuel M. Smucker (New York, 1856), reproduced online here. Frémont ran for president that year; Smucker’s “memoir” is actually a campaign biography, attached to a reprint of the 1845 edition of the first two expedition reports. The most comprehensive edition of Frémont’s reports is still in print as The Expeditions of John Charles Frémont, ed. by Donald Jackson and Mary Lee Spence (Urbana, 1970), in four volumes, of which the fourth is a beautifully produced map portfolio. And map lovers may want to purchase the seven-section, ten-miles-to-the-inch Topographical Map of the Road from Missouri to Oregon Commencing at the Mouth of the Kansas in the Missouri River and Ending at the Mouth of the Wallah Wallah in the Columbia, available in inexpensive facsimiles from Southfork Publications, P.O. Box E, Dayville, Oregon 97825.

Frémont published the first volume of his Memoirs of My Life in 1887; it covered his first three expeditions. But when it sold poorly, he did not follow it up with the successive volumes that had been planned. A new edition from Cooper Square Press in New York, 2001, is now in print, with an introduction by Charles M. Robinson.

The story of uncrating the odorous rubber boat in the Benton household is told in the Memoirs, and in more detail in Catherine Coffin Phillips’s Jessie Benton Frémont: A Woman who Made History (San Francisco, 1935). The book is based on long interviews the author conducted with Jessie before she died in 1902.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.4 (July, 2004).

Tom Rea’s Bone Wars: The Excavation of Andrew Carnegie’s Dinosaur, is just out in paper from the University of Pittsburgh Press. This essay is adapted from a new book, The Middle of Nowhere, due from the University of Oklahoma Press in 2005. He lives in Casper, Wyoming.