Farmers, Tenants, and Capitalists

In Farm, Shop, Landing, a sprightly book about the mid Hudson River Valley counties of Columbia and Greene, Martin Bruegel has boldly entered into the long-running debate over economic development and the so-called “market revolution” of post-Revolutionary America. Breugel argues that the primacy of the market—where supply and demand determined price and where farmers and artisans strove for profit over security—emerged in the Hudson River Valley during the early nineteenth century, when waged labor, agricultural specialization, long-distance markets, and industrial development began. Before then, farmers ran diversified farms because they wanted a sufficiency, wanted to produce enough to feed their families and to swap with neighbors and storekeepers for what they could not grow or make.

Bruegel builds his case through a wealth of detail about farm operations, commerce, and industry garnered from both literary and quantifiable sources. He has thoroughly researched manuscript collections, newspapers, court records, tax digests, and probate records. Far from adopting the style of a cliometrician, Bruegel peoples his book with the stories of men and women struggling to comprehend economic changes occurring all around them, gradually changing their behavior, forming new voluntary associations, and building new (classical) liberal ideologies to defend their innovations.

I find the evidence, but not the arguments, of Bruegel’s book persuasive. The evidence suggests that a market economy and society emerged in the Hudson River Valley long before the late eighteenth century, when Breugel begins his book. The economic changes Bruegel finds demonstrate something different—a transition to capitalism, complete with the formation of classes of bourgeois factory owners and merchants, petty-producer farmers, and debased proletarians. To show the utility of such a framework, I will briefly analyze the region’s political geography, forms of local and market exchange, economic development, and patterns of political conflict.

The political geography and settlement patterns of the Hudson valley made a big difference in the forms and timing of economic development found there, as Bruegel would be the first to recognize. The area contrasted greatly with nearby communities in western Massachusetts and on Long Island. Although the first European inhabitants arrived early in the seventeenth century, substantial Euro-American settlement did not occur until the mid-eighteenth century at the earliest. The reasons are not hard to discover. Greene County, half the area Bruegel studies, was hilly, even mountainous, hardly ideal territory for farmers seeking to cultivate grains with hand tools and wooden plows. Great landlords who refused to sell land to would-be farmers dominated the other, potentially more productive half, Columbia County. Conflicts between landlord and tenant broke out repeatedly, starting in the 1750s and not ending until the 1840s, where landlords finally lost their feudal rights. This political geography retarded economic development until the middle decades of the nineteenth century, leaving the region far behind New England.

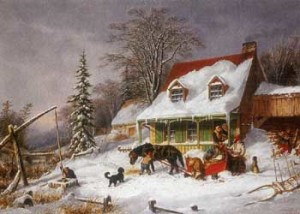

Bruegel draws a compelling picture of farmer exchange in the late eighteenth century. Like farmers nearly everywhere in North America, those in the Hudson River Valley, whether freeholders or tenants, strove for safety first. They created and sustained a “borrowing system,” to use John Mack Faragher’s felicitous phrase. Given the precarious conditions of life—warfare, floods, droughts, pestilence—they sought first to feed and clothe their families and then to produce small surpluses to trade with neighbors or at the marketplace. As a result, only a tiny number of farmers sold grain or other goods bound directly for distant or foreign markets. Both men and women exchanged labor with neighbors, particularly at harvest and house raising, but through the year as well; they swapped goods without demanding regular payments.

Face-to-face interpersonal relations took on far more importance in this society than abstract, impersonal economic relations, symbolized by commercial paper (whose origin might be unknown) or distant banks. Even merchants were caught up in these intense personal relations, each demanding that they know the character of those with whom they traded. Close (not necessarily conflict-free) relations permeated the culture as well. Men insisted that others recognize their integrity and honor, and if they did not, fought or took them to court. Noisy rituals of shaming—skimmingtons or rough music—commonly occurred when middling folk wanted to distinguish themselves from their debased inferiors, especially when a woman or man of low character married.

This portrait of eighteenth-century Hudson River Valley society rings true but it is incomplete. Class conflicts, such as the anti-rent rebellions, permeated the region, beginning in the 1750s, and exploded during the Revolutionary Era and the 1790s. Rebels sought to overthrow the manorial system, replace manorial government with their own courts, and during the Revolution, tenants everywhere in the region along the Hudson chose a different side than their lords, whom they loathed. These rebellions never become a major part of Bruegel’s analysis of economic development (or the lack of it), despite his acknowledgment of their importance and his publication of a major article in 1996 in the Journal of American History on the topic. Instead, eighteenth-century farmers and tenants, in Bruegel’s telling, as well as great landlords usually supported a hierarchical society (one of ranks or orders), where inferiors obsequiously deferred to superiors and where superiors patronized inferiors.

In addition, Bruegel minimizes the level of commercial activity in the region, insisting that few households participated in the market. Farm-gate prices for commodities like wheat, he contends, failed to follow New York City prices until sometime in the nineteenth century (his evidence is from 1824), when they had converged. But his data are hardly conclusive, for he provides no eighteenth-century farm-gate price series.

Breugel’s evidence suggests that nearly everyone participated, directly or indirectly, in commercial markets, where supply and demand determined price, even if few farmers sold goods directly. First, the borrowing system depended upon commercial markets to operate, for everyone needed some minimal cash, available only through commercial transactions. Second, farmers’ surpluses did regularly reach New York City (and beyond); tenants, in particular, sold their wheat to their landlords (their leases demanded it) and poorer and middling farmers probably followed suit, selling to wealthier neighbors who then sent grain downriver. Third, Bruegel exaggerates the significance of face-to-face relations for merchants. All merchants, no matter how small, had to pay for the goods they bought with commercial paper, usually on a short timeframe. They could afford to carry farmers year in and year out and provide “book” credit, which allowed gradual repayment, only if they, like merchants elsewhere in early America, instituted a two-price system, where cash customers paid far less for goods than those who needed credit.

A commercial, market society, then, had come to the Hudson River Valley long before the nineteenth century, and the market revolution, if there ever was one, took place in late medieval England. Yet Bruegel documents, persuasively, massive economic change in the region, particularly in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s. The proportion of farmers selling goods (wheat, other grains, hay) to merchants increased markedly; specialization took hold, with farmers abandoning grain production (western New York and the Ohio country grew it more cheaply) for herding, dairying, and haying; farmers hired more and more wage laborers, both at harvest and for longer terms of six months or more; textile mills (at first, with weaving outwork), tanning operations, and brick-making factories opened. As economic development proceeded, the utility of the borrowing system diminished. Farmers still swapped goods and labor, but more and more middling farm folk participated in market relations, buying food and cloth and acquiring manufactured goods they had never been able to afford before.

Economic development (as well as population growth) led to increased land prices; higher land prices, population growth, and in-migration probably led to relative land scarcity and encouraged the growth of a class of wage laborers (at first mostly young) as well as increasing the wealth of the middling sorts. Such changes in productive relations, cemented by the attack on feudal tenures (actually, the increasing demands of landlord for capitalist ground rent) by a “liberal” and capitalist-leaning faction of the ruling class, sustained, in my view, an ever growing capitalist revolution.

How can we explain such developments, and particularly their timing? Economic transformation began in New England perhaps two decades earlier than in the Hudson River Valley. The long-term, and disastrous, effects of tenancy go a long way to explaining the timing of economic change. Prominent Yorkers had complained long before the nineteenth century that tenancy retarded population growth and economic development. Tenants, as Breugel indicates, understood the problem differently: they would improve their holdings only when they actually owned them and could reap the fruits of their own labor. Their labor (not some feudal legal doctrine) gave their land value, and they deeply resented the expropriation (of both product and labor time) of their output. (A Marxist would define such behavior as “exploitation,” the taking of surplus value). The destruction of fratricidal civil war during the Revolution set back economic development even more. The expansion of population into less hospitable freehold areas and the expropriation of some (Tory) estates after the Revolution opened up new land for development, while—at the same time—the growing manorial population demanded freeholds (sometimes violently). Such a confluence of events, Bruegel’s evidence suggests, created and sustained capitalist development.

I seriously doubt that Bruegel would accept my spin on his evidence. He adopts definitions of commerce and class that come out of Max Weber’s sociology; I tend to a more Marxian exposition. Yet no matter what framework one adapts, Farm, Shop, Landing does raise significant questions about the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, ones others might research. Bruegel, for instance, does not distinguish the behavior of tenants and freehold farmers, assuming similarities instead. Yet the analysis here suggests that differences ought to have occurred, with tenants engaging in less developmental activity, less often adapting specialized agriculture than their freehold neighbors of similar wealth. Nor does he directly connect the tradition-bound behavior (shaming ceremonies, the strong borrowing system) he observes to the persistence of the manorial system.

On the first several pages of Farm, Shop, Landing, Bruegel opens up the question of capitalist development. He demonstrates that the word “capital” did not appear in the region until around 1800 but by the 1830s and 1840s came to represent the impersonal relations of a market society. Following Bruegel’s lead, early Americanists should turn to the issue of capitalist development, whether dubbed a market revolution or a transition to capitalism, in other regions of early America.

This article originally appeared in issue 3.3 (April, 2003).

Allan Kulikoff, the Abraham Baldwin Distinguished Professor in the Humanities, department of history, University of Georgia, has had a long interest in early American rural societies, publishing three books—Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake (Chapel Hill, 1986); The Agrarian Origins of American Capitalism (Charlottesville, 1992); and From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (Chapel Hill, 2000). He is currently working on three book-length projects: Reinventing Early American History, The Making of the American Yeoman Class, and The Farmer’s Revolution.