Mary (? – ?)

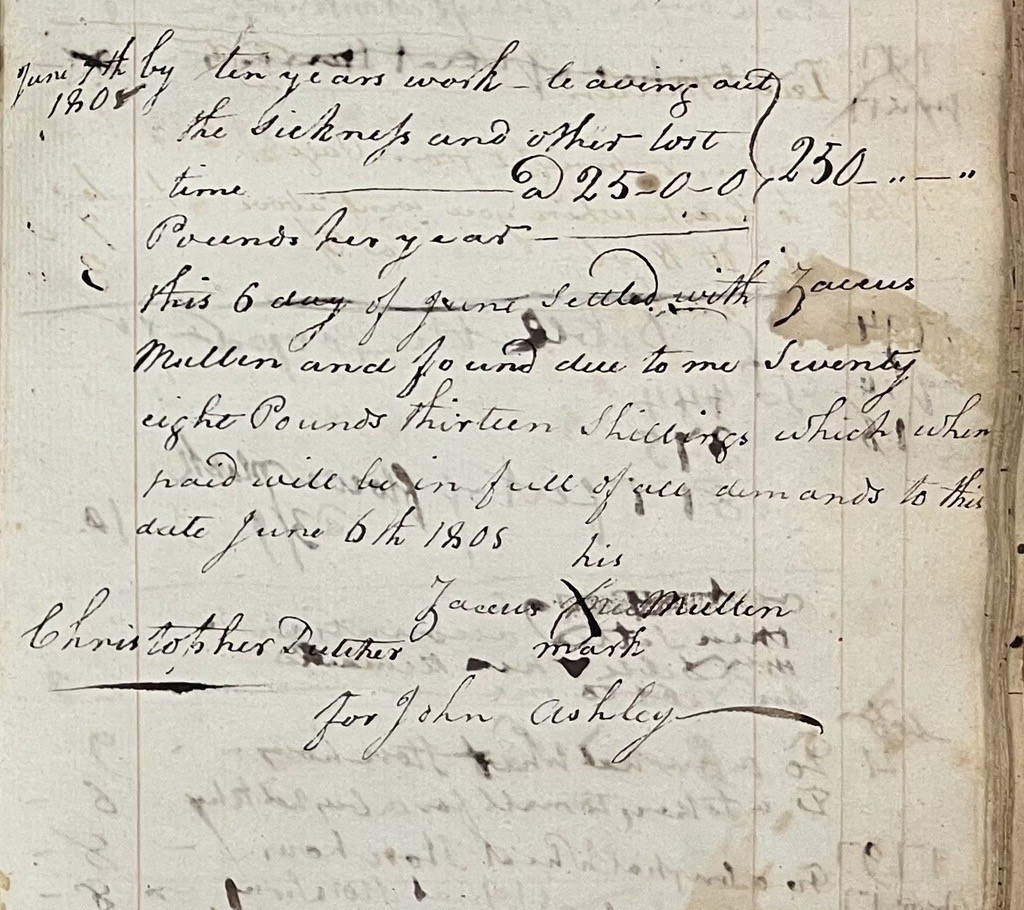

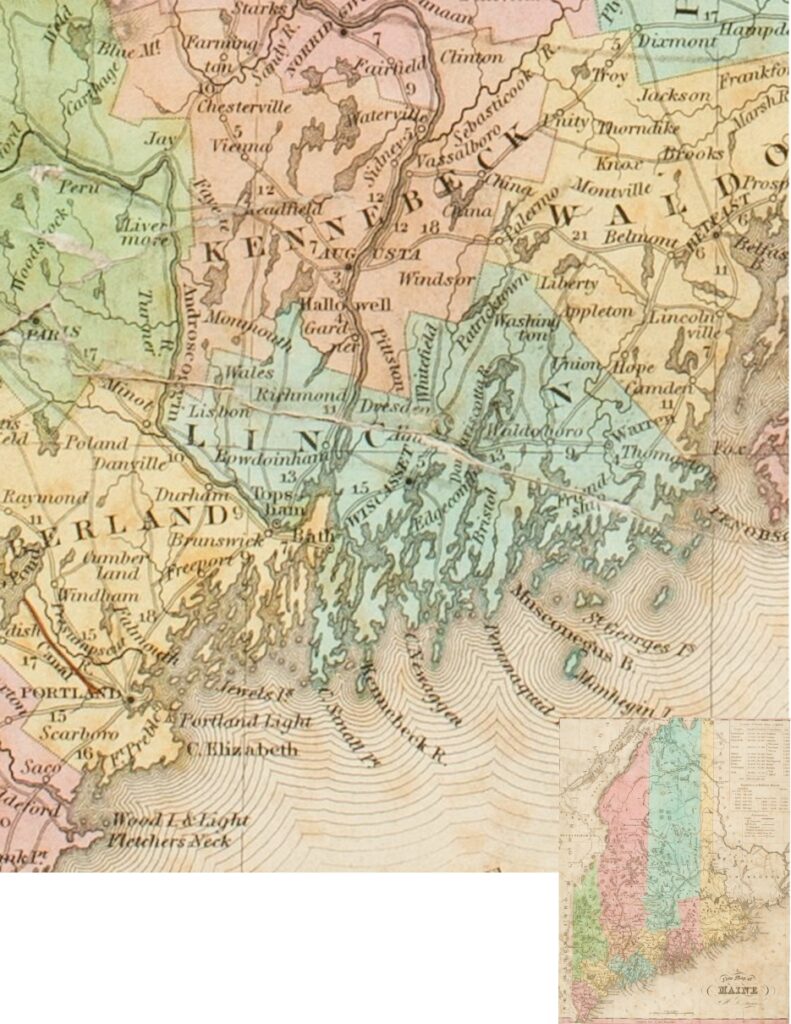

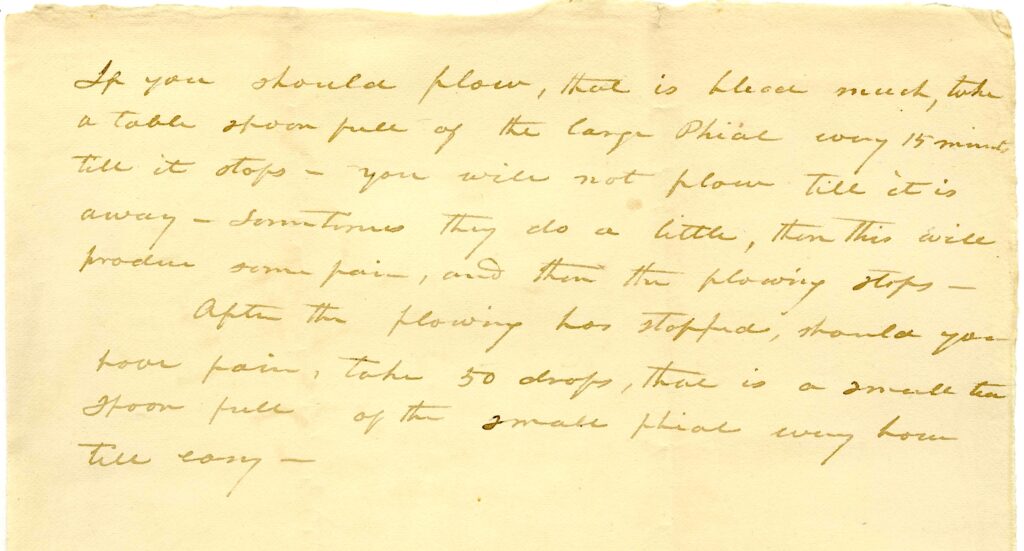

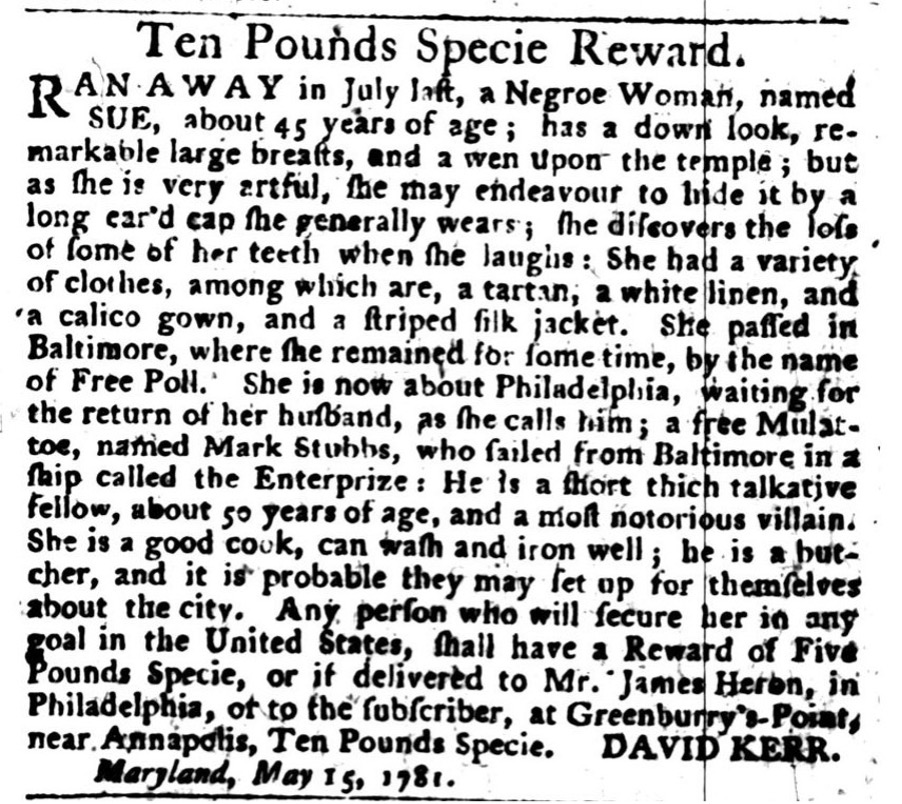

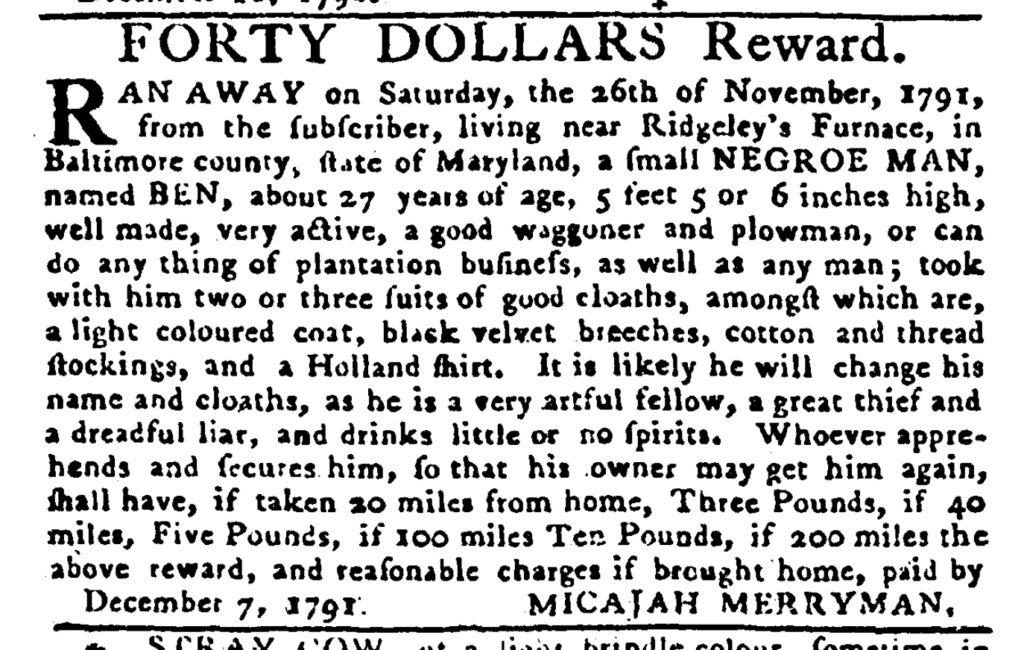

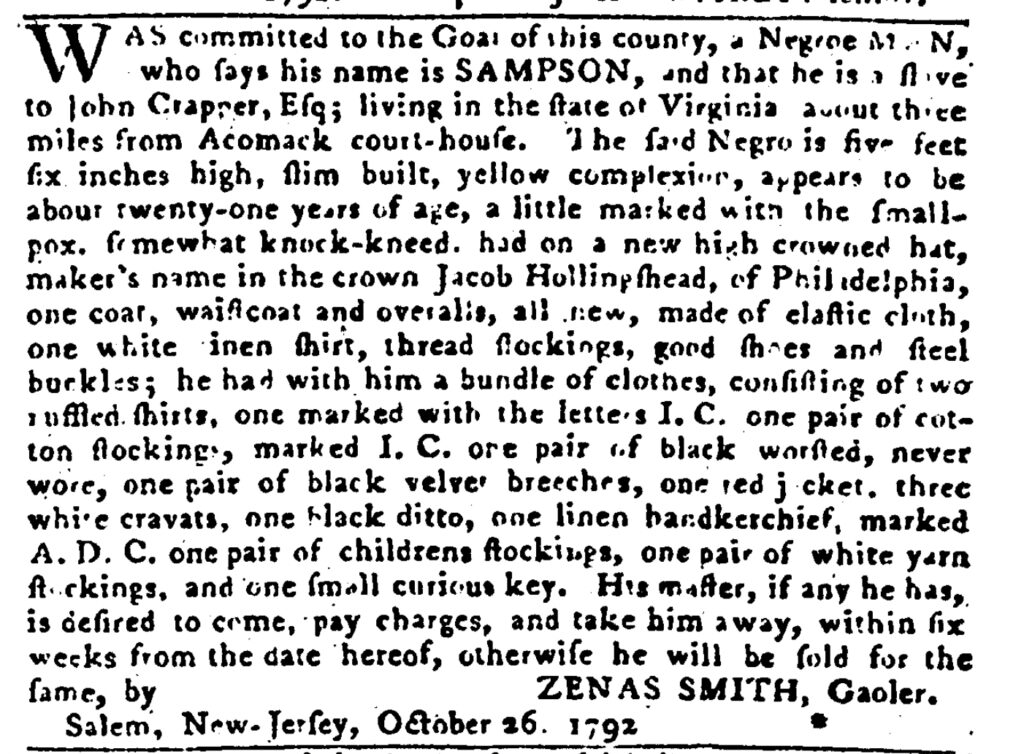

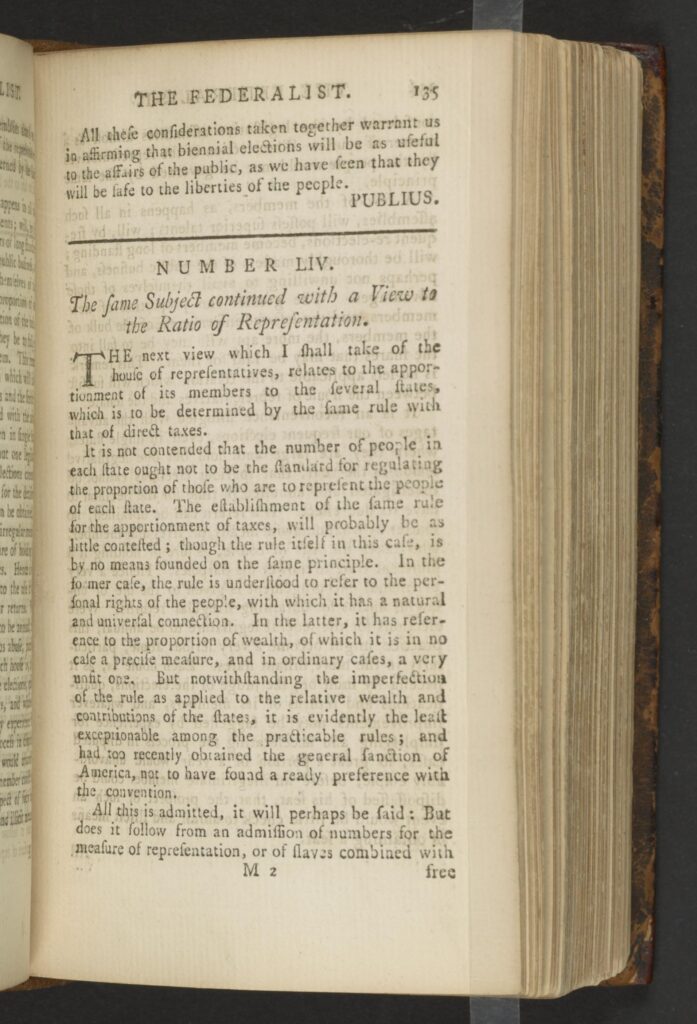

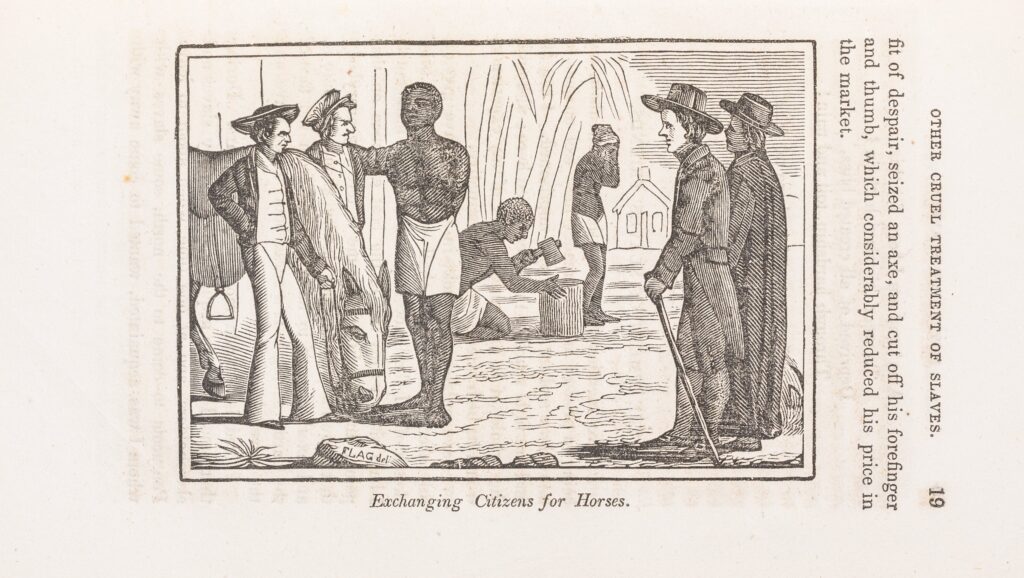

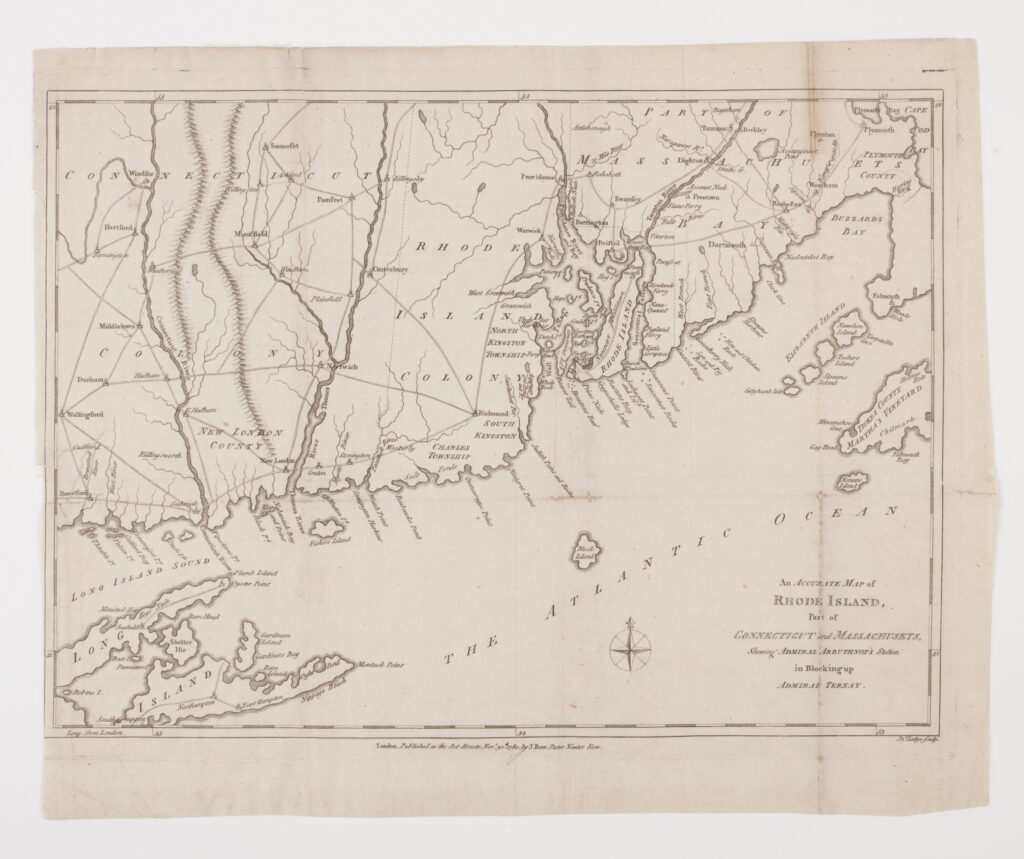

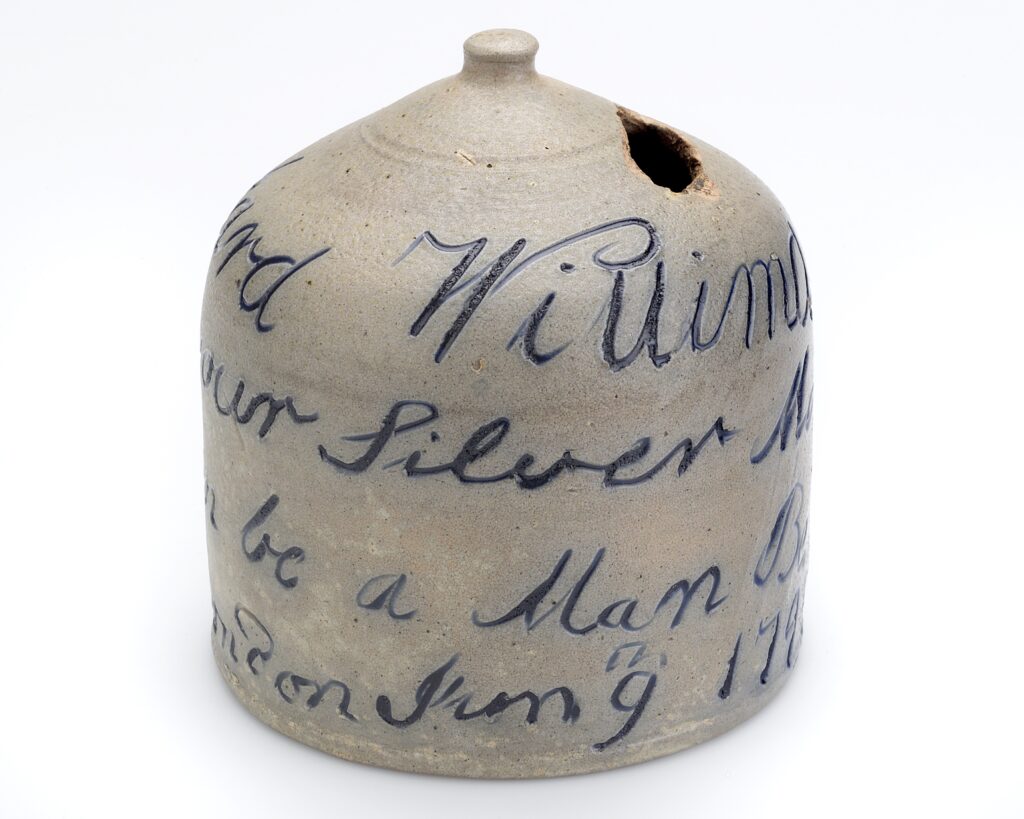

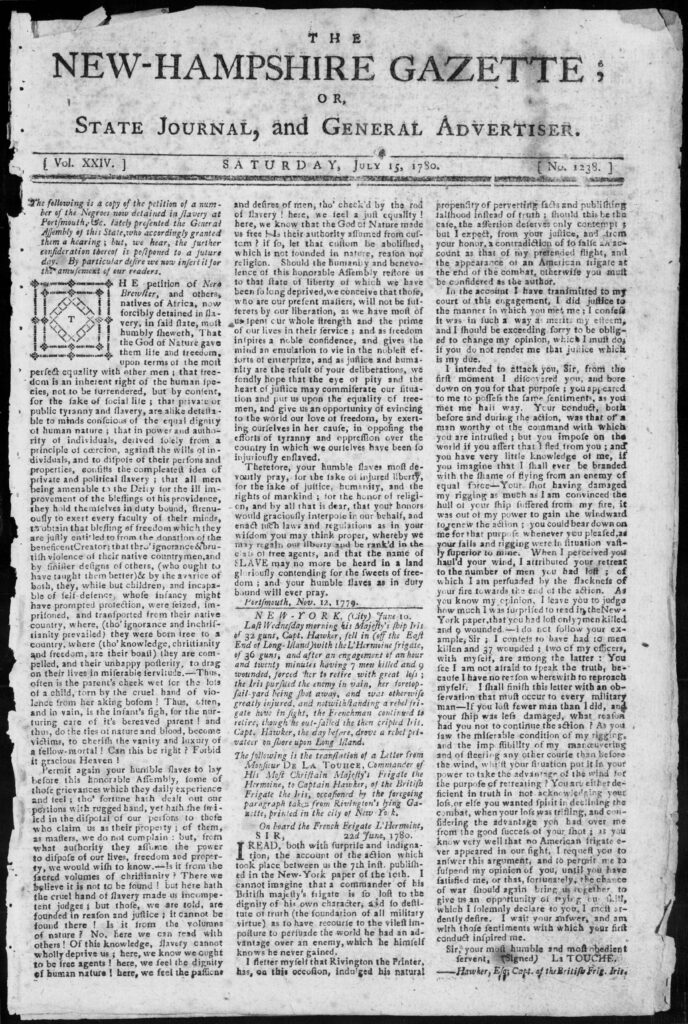

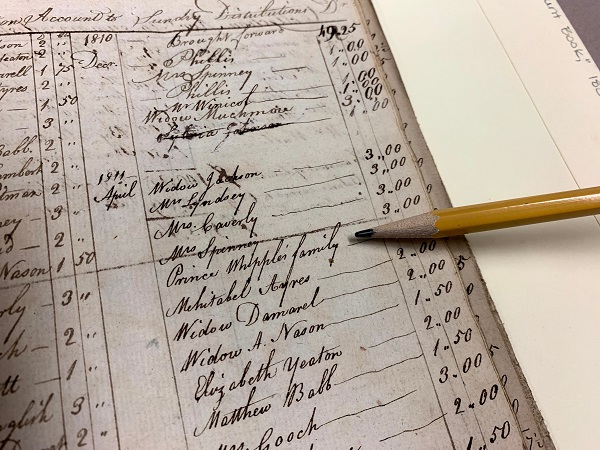

Mary was formerly enslaved to William Van Ness (1710–ab. 1790) of Claverack—the husband of Hannah Hogeboom Ashley’s sister. On May 5, 1789, General John Ashley Jr. purchased the “time” of “Mary a negro woman” in an indenture agreement. General Ashley first bought Mary from William Van Ness, freed her, and then rebound her to him as an indentured servant for ten years. Scholar Joanne Pope Melish described this indenture as supposedly being an arrangement Mary “agreed” to, but “Mary’s agreement would almost certainly have been made under duress on “free” ground in Massachusetts as the only way out of continued enslavement in New York. This kind of pressured service, whose legality seems dubious at best, was obviously calculated to extend the slave relation rather than to mitigate it.” Colonel Ashley recorded in his account book that “General Ashley sent to Wm Van Ness” on August 4, 1789 “10:0:24 of iron in which was 2 set of wagon tire,” possibly as a partial payment for the purchase of Mary. She may have been related to other enslaved people possibly inherited by members of the Hogeboom family from the patriarch Pieter Hogeboom (1676–ab. 1758). Right before the death of Gen. Ashley in 1799, Mary’s indenture to the family ended. The details of her life after her indenture ended are unknown.

***************************************

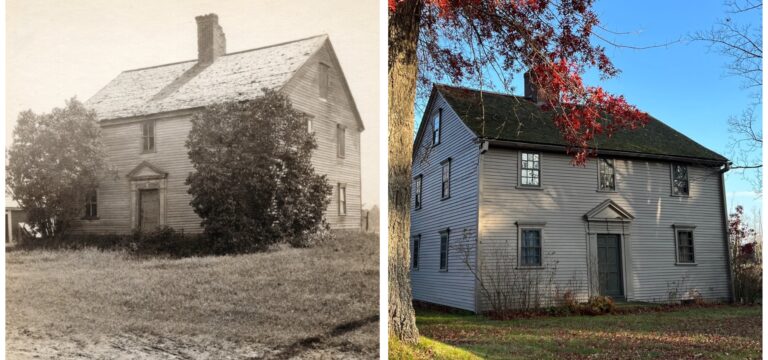

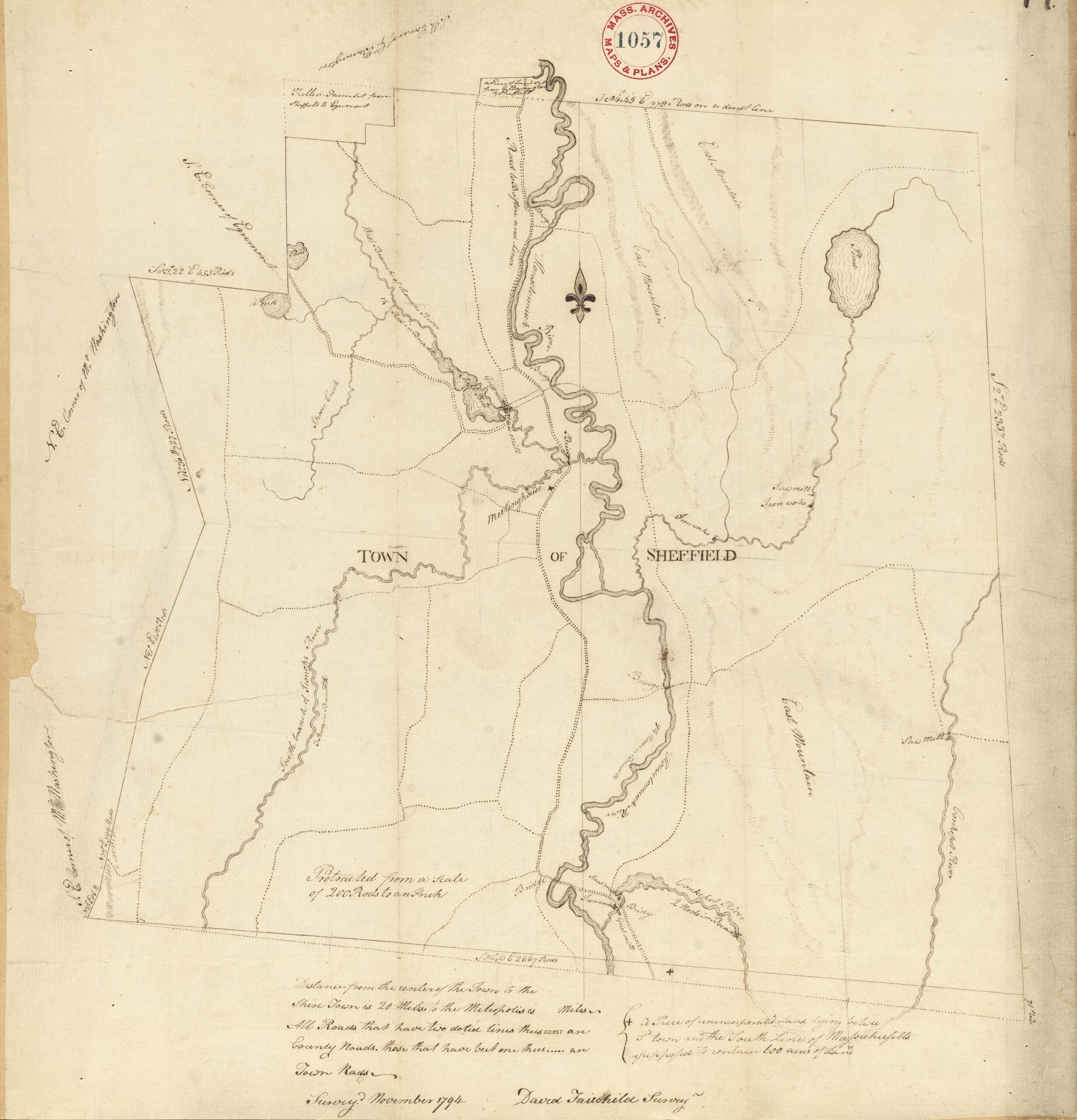

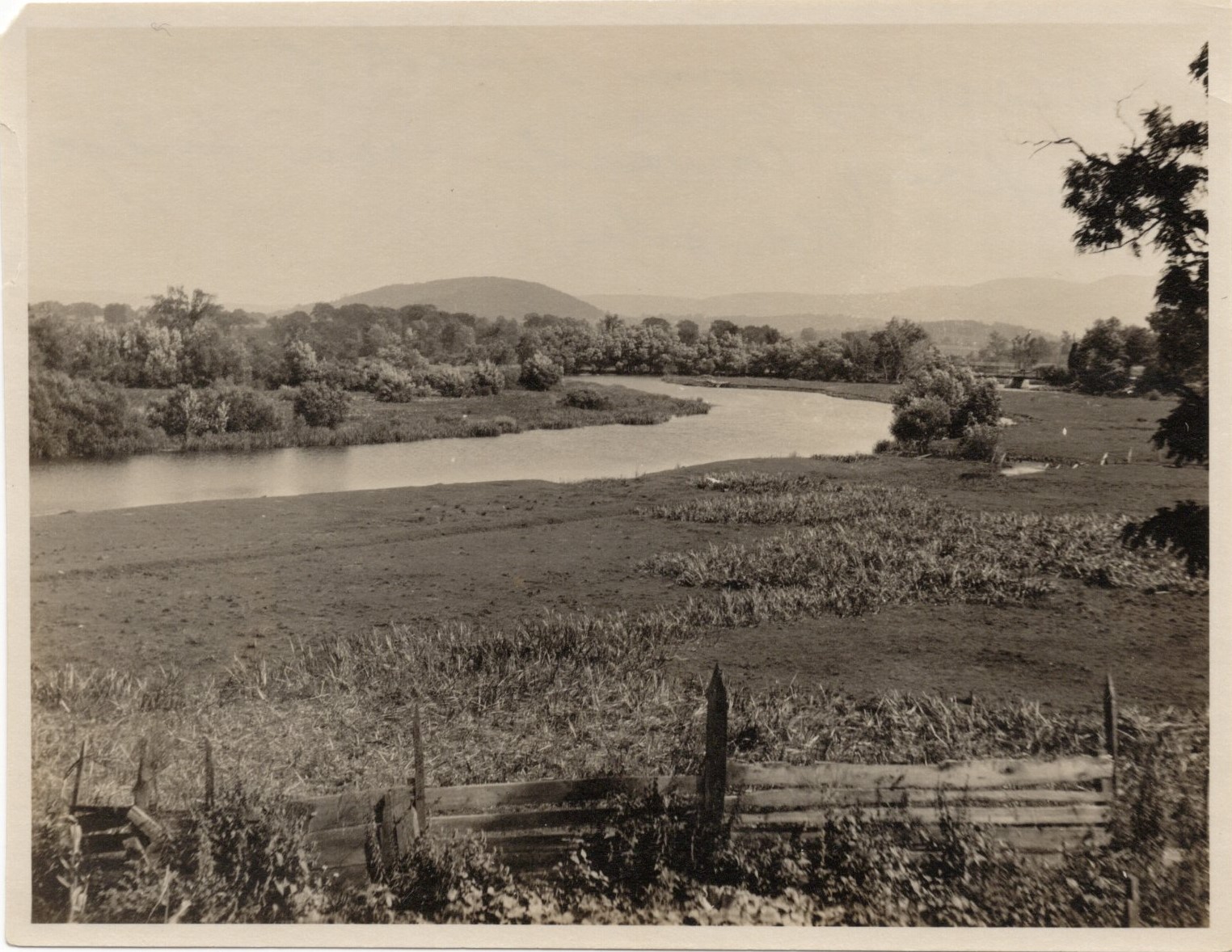

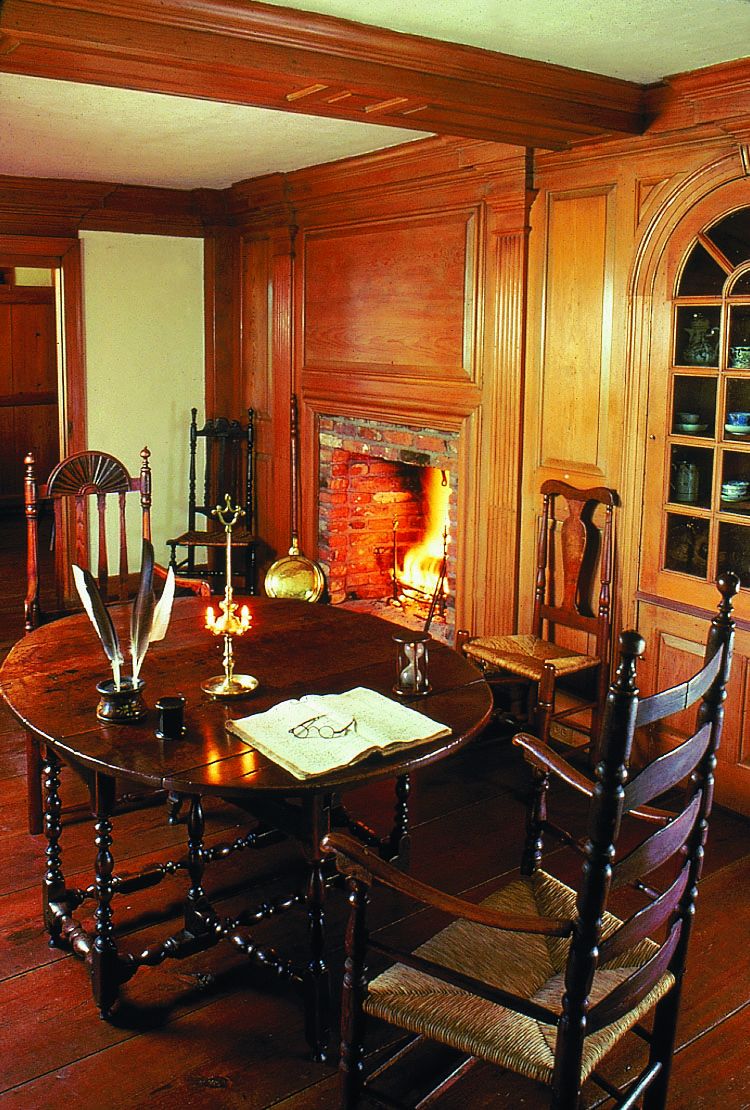

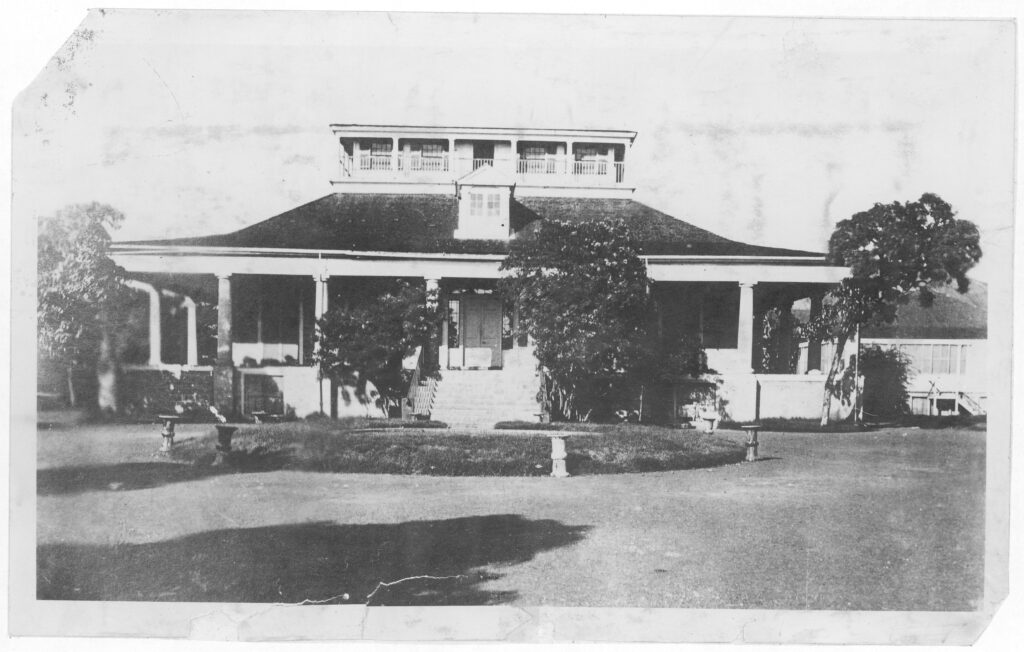

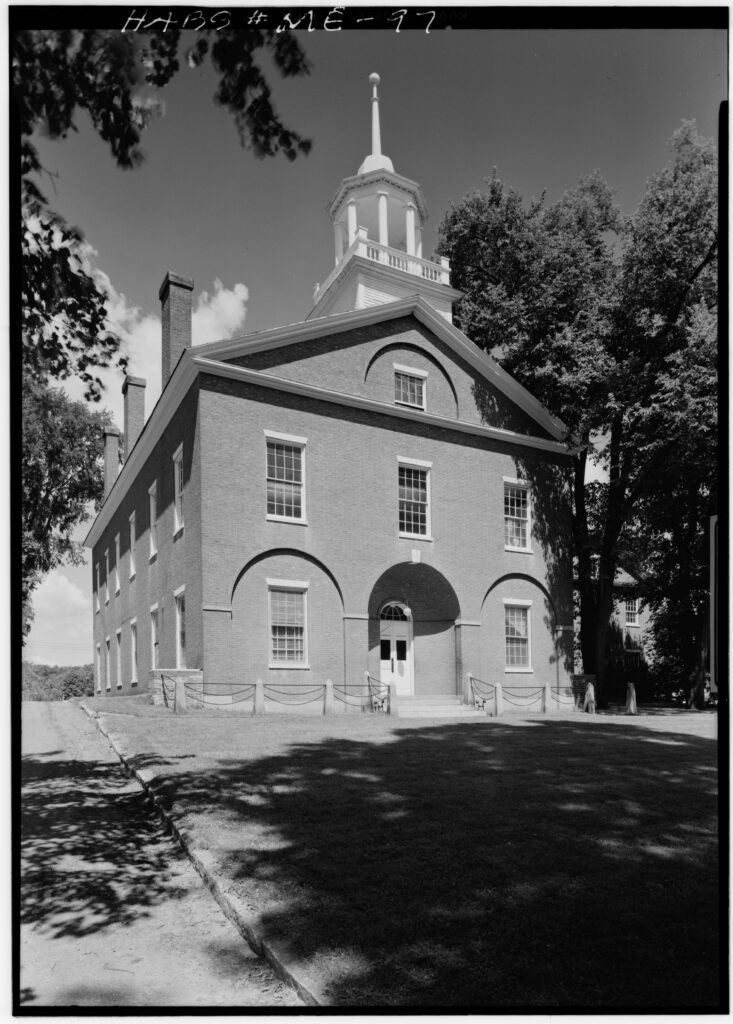

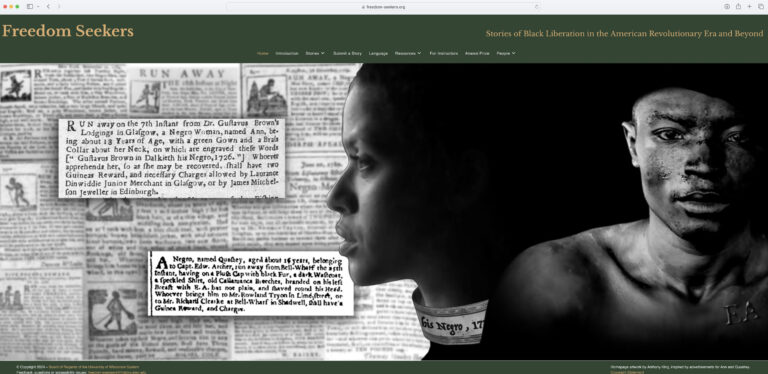

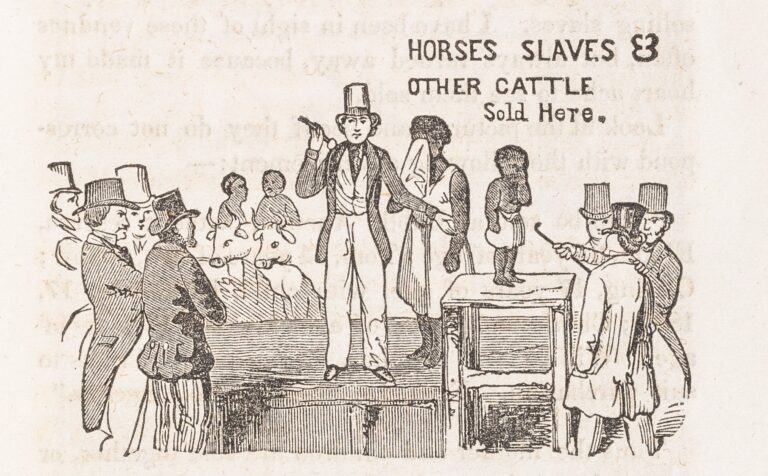

As is the case with many historic house museums, the Colonel John Ashley House’s role as a public institution began as a testament to a triumphant war hero and local legend of Sheffield, centering elite white male identity in the process. Narratives around Elizabeth Freeman and certainly the identities of any enslaved or free laborers existed only secondarily. Yet, the Ashley family and the wider Sheffield community’s maintenance of the Colonel Ashley House and its family history resulted in the critical preservation of historical materials. The survival of thirty family account books enables a reevaluation of its history. Revisiting archival material related to the Ashleys and the production of these biographies allows for a new type of engagement and interpretation of the house. As we enter the first stages of the house’s reinterpretation, The Trustees of Reservations is committed to illuminating all the stories of those who lived and were enslaved in the Colonel Ashley House in tangible, permanent, and meaningful ways. The Colonel Ashley House Interpretation Center, situated in a separate building open year-round, will receive a refurbishment and a new exhibition based on these findings. A part of this approach will be to better explicate how the Colonel Ashley House has physically evolved over time through visual aids. This is an important aspect of the conversation surrounding how spaces that enslaved individuals lived and slept in may no longer be accurately reflected in the surviving structure, or even exist. Along with the inclusion of these biographies, the new interpretation within the house will recenter and better educate the public on how the realities of everyday life in bondage in the Colonel Ashely House and rural New England more generally. This ongoing, multi-phase reinterpretation will seek to engage other nonprofit organizations and the Black community to make an impactful and enduring contribution to raise awareness about slavery in the North and its enduring consequences.

Further Readings and Notes on the Sources:

The following account books are referenced throughout this article in abbreviated form. To mitigate the further spread of myths and misinformation regarding those enslaved at the Col. Ashley House, these biographies derive from evidence found in surviving primary source materials and the below citations provide references for retracing such information. The thirty surviving account books are accessible to the public by appointment at The Trustees of Reservations’ Archives & Research Center in Sharon, MA and the Sheffield Historical Society’s Mark Dewey Research Center in Sheffield, MA.

Colonel John Ashley, Ashley Account Book 1, Ledger, 1768-1786, Colonel John Ashley Papers, 1755-1818, The Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

Colonel John Ashley, General John Ashley, and William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 2, ledger, daybook, memorandum, 1777-1819, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

Colonel John Ashley, and General John Ashley, Ashley Account Book 3, ledger, memorandum, 1786-1796, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

General John Ashley and William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 5, daybook, 1794-1795, Colonel John Ashley Papers, 1755-1818, The Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

General John Ashley and William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 7, daybook, 1796, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

General John Ashley et al., Ashley Account Book 9, daybook, ledger, 1798-1801, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 10, index, ledger, 1791-1805, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 11, daybook, 1799-1806, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

William Ashley, General John Ashley, and John Ashley 3rd, Ashley Account Book 12, daybook, memorandum, 1792-1812, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 15, daybook, 1806-1807, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

William Ashley, Ashley Account Book 18, daybook, memorandum, 1819-1826, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center.

On slavery in the North and public memory, see Joseph Carvalho, “Uncovering the Stories of Black Families in Springfield and Hampden County, Massachusetts: 1650–1865,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Vol. 40, no. 1/2 (Summer 2012): 70–3; Nicole Saffold Maskiell, Bound by Bondage: Slavery and the Creation of a Northern Gentry (Cornell University Press, 2022), 17–8, 23; Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000); Marla R. Miller and Karen Sánchez-Eppler, “Joining Reinterpretation to Reparations,” Museums & Social Issues 15, no. 1–2 (July 3, 2021): 75–6; Andrea C. Mosterman, Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2021), 67; William Dillon Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 117–21, 136; Marc Howard Ross, “Slavery and Collective Forgetting,” in Slavery in the North: Forgetting History and Recovering Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 94–5, 99, 118; Elena Sesma, “‘A Web of Community’: Uncovering African American Historic Sites in Deerfield, MA,” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 2, no. 2 (May 18, 2015): 133; and Gloria McCahon Whiting, “‘Race, Slavery, and the Problem of Numbers in Early New England: A View from Probate Court,’ William and Mary Quarterly 77 No. 3 (July 2020): 405-40.

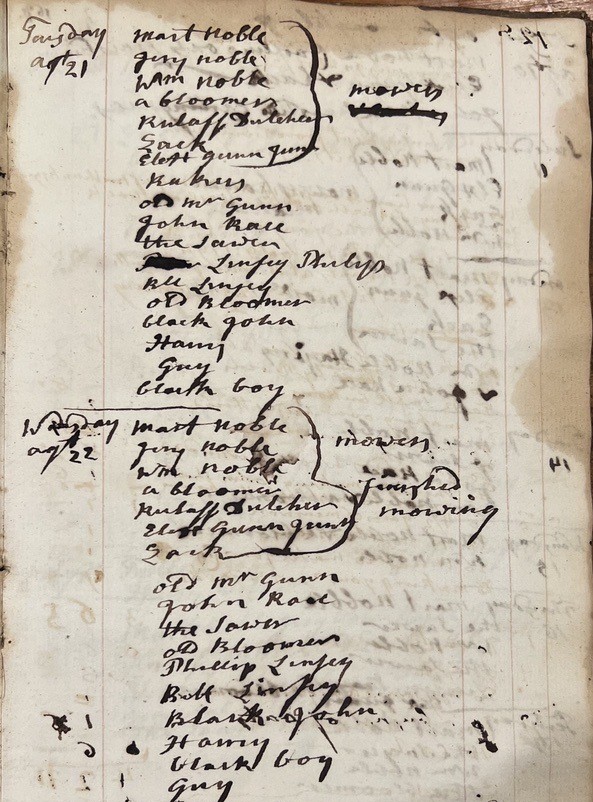

On background of enslavement at the Colonel John Ashley House, see “Entry for John Ashley,” Sheffield, The Massachusetts Tax valuation List of 1771, Massachusetts State Archives, volumes 132-134; Ashley Account Book 1, 165–6, 173–4, 199, 222–3, 226–9, 291, 294–6; Colonel John Ashley, “Notes regarding work of “Adam” for John Ashley,” 1784-1785, note laid in Account Book 1 (pp. 160), Colonel John Ashley Papers, 1755-1818, Archives & Research Center, The Trustees of Reservations. Ashley Account Book 3, 113–6, 127–8, 133; Ashley Account Book 10, 47; Ashley Account Book 2, 28, 46, 56; “John Ashley, Esq., Sheffield 1802 (Record no. 2195),” in Berkshire County, MA: File Papers, 1761–1917, vol. 1: Berkshire Cases 2000–3999, 5; “Entries for Sheffield,” U.S. Census, 1790, 1800, Sheffield, Massachusetts; and Myron Stachiw, “Col. John Ashley and His Web of Commerce, 1735-1802,” unpublished report (Sheffield, MA: The Trustees of Reservations, 2002); Bernard A. Drew, If They Close the Door on You, Go in the Window: Origins of the African American Community in Sheffield, Great Barrington & Stockbridge (Great Barrington, MA: Attic Revivals Press, 2004).

For the biography of Brom, see: “Christopher Dutcher,” September 15, 1752, Probate Records, 1743-1817: Probate Court, (Litchfield District), 101–5; Ashley Account Book 1, 112, 174, 167, 205, 210, 237, 245, 256, 266–7, 281, 300, 306; George Ballantine, ed., Journal of Rev. John Ballantine: Minister of Westfield, MA, 1737-1774 (Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc., 2002), 2443; Brom & Bett vs. J. Ashley Esq, Court Records, Berkshire County Courthouse, Great Barrington, Mass., Inferior Court of Common Pleas, May 28, 1781, vol. 4A; Emilie Piper and David Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman: Elizabeth Freeman and the Struggle for Freedom (Salisbury, CT: Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area, 2010) 132, 136–7; Gelston Hardy, “Mum Bet vs. Ashley: A Little-Known Case Involving Slavery Which, If It Had Been Followed NATIONALLY, Might Have Prevented the CIVIL WAR,” unpublished paper, (Dewey Research Center: Sheffield Historical Society, 1974), 2–3; Drew, If They Close the Door on You, 11, 44; “Catharine Maria Sedgwick to Theodore Sedgwick I,” Stockbridge, MA, April 1, 1804, Catharine Maria Sedgwick Online Letters, Massachusetts Historical Society; Catharine Maria Sedgwick, The Power of Her Sympathy: The Autobiography and Journal of Catharine Maria Sedgwick, ed. Mary Kelley (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1993), 110.

For the biography of Caesar, see: Ashley Account Book 1, 174, 245, 256, 267, 287, 300; Ashley Account Book 2, 42; Ashley Account Book 11, 250; Ashley Account Book 9, 61, 63, 70, 75, 84, 87, 115, 124, 139, 150, 160, 184, 200, 211, 271, 296; Sheffield, Massachusetts Assessor’s Tax Lists and Records, Sheffield Historical Society, Mark Dewey Research Center, year 1798; “Entry for Caezar Freeman,” July 29, 1844, Massachusetts State Vital Records, 1841-1925, Deaths Registered in Sheffield 1845.

This Caesar Freeman of Sheffield and Great Barrington should not be confused with the Caesar Freeman of Stockbridge that married Margaret “Peggy” Hull, sister of Agrippa Hull.

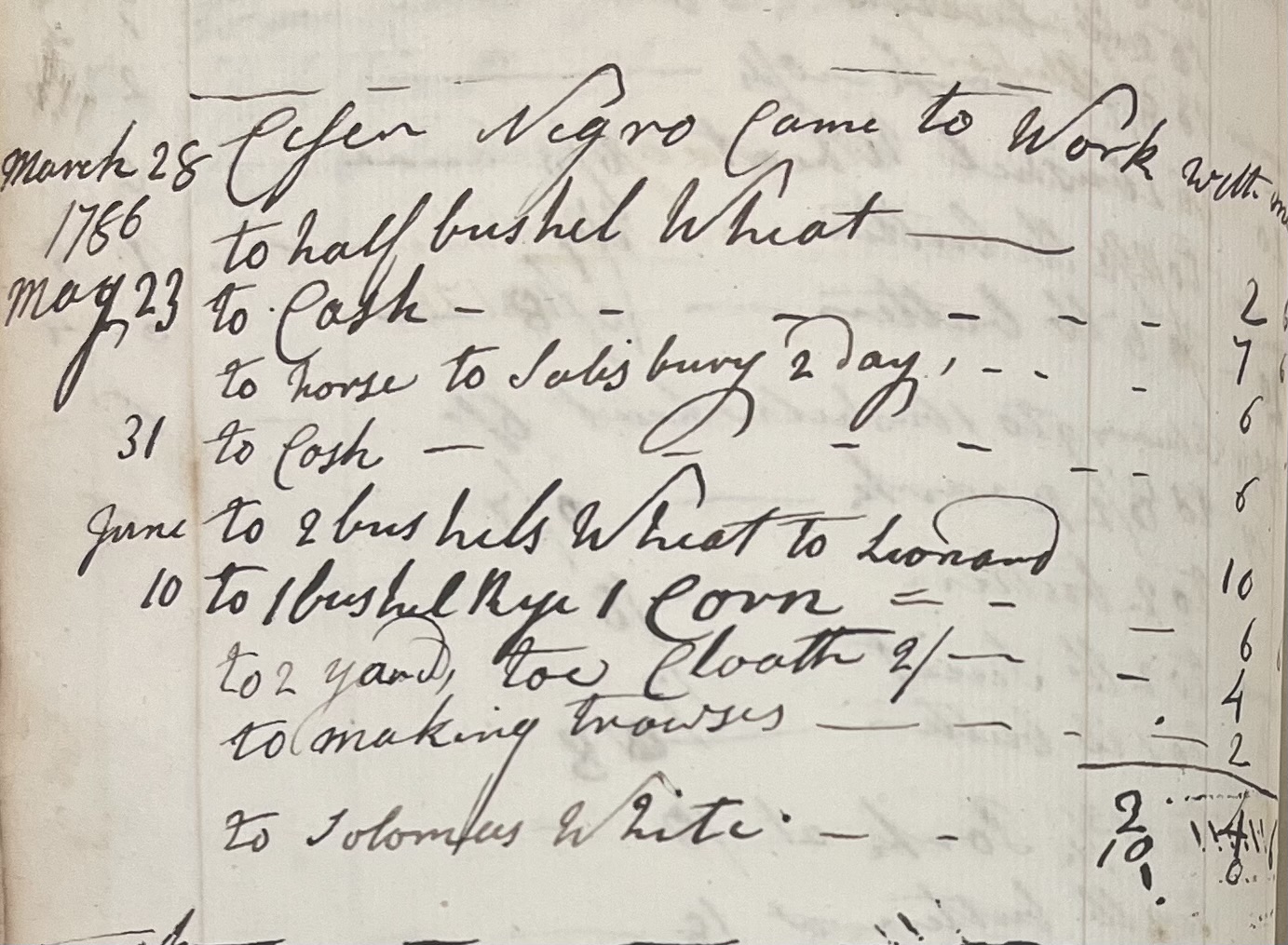

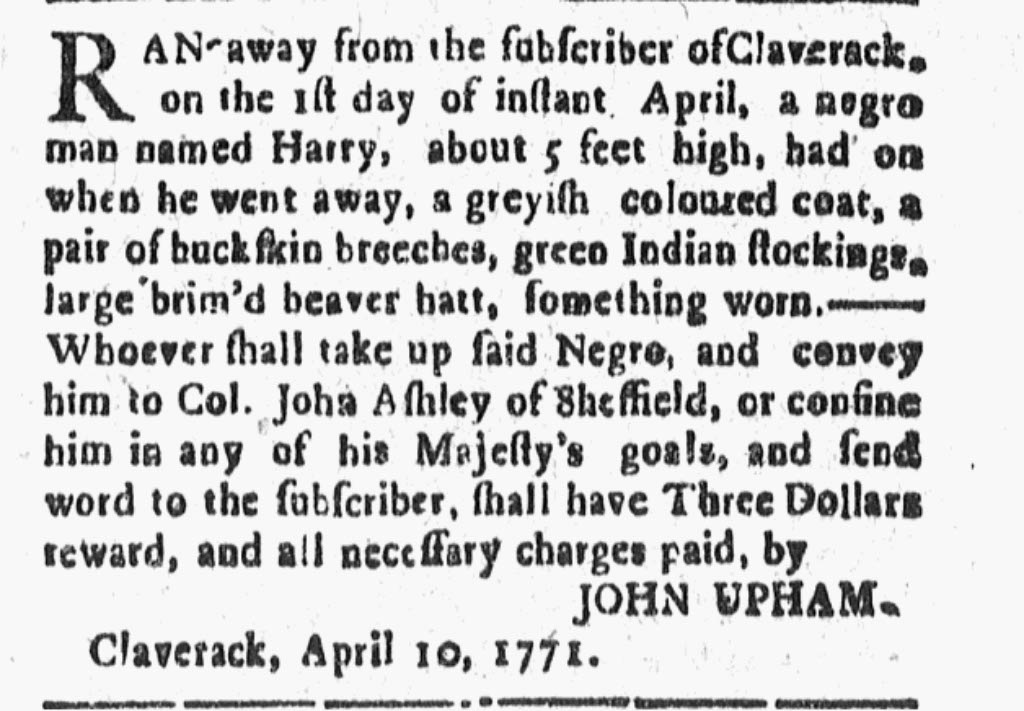

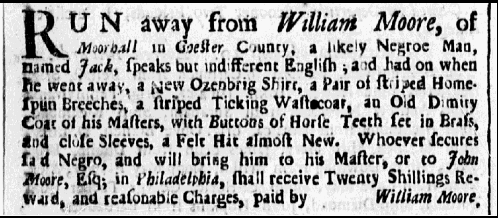

For the biography of Harry, see: “Runaway Advertisement for Harry,” Connecticut Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), no. 329, April 16, 1771, 3; Ashley Account Book 1, 107; Ashley Account Book 3, 21, 42, 46, 61, 102, 108, 117, 124-5, 128, 130, 197; Ashley Account Book 5, 70; Ashley Account Book 2, 75, 163, 181–2, 223, 226, 247, 256, 270–7; Sheffield, Massachusetts Assessor’s Tax Lists and Records, year 1791; “John Ashley, Esq., Sheffield 1802 (Record no. 2195),” NEHS, 5.

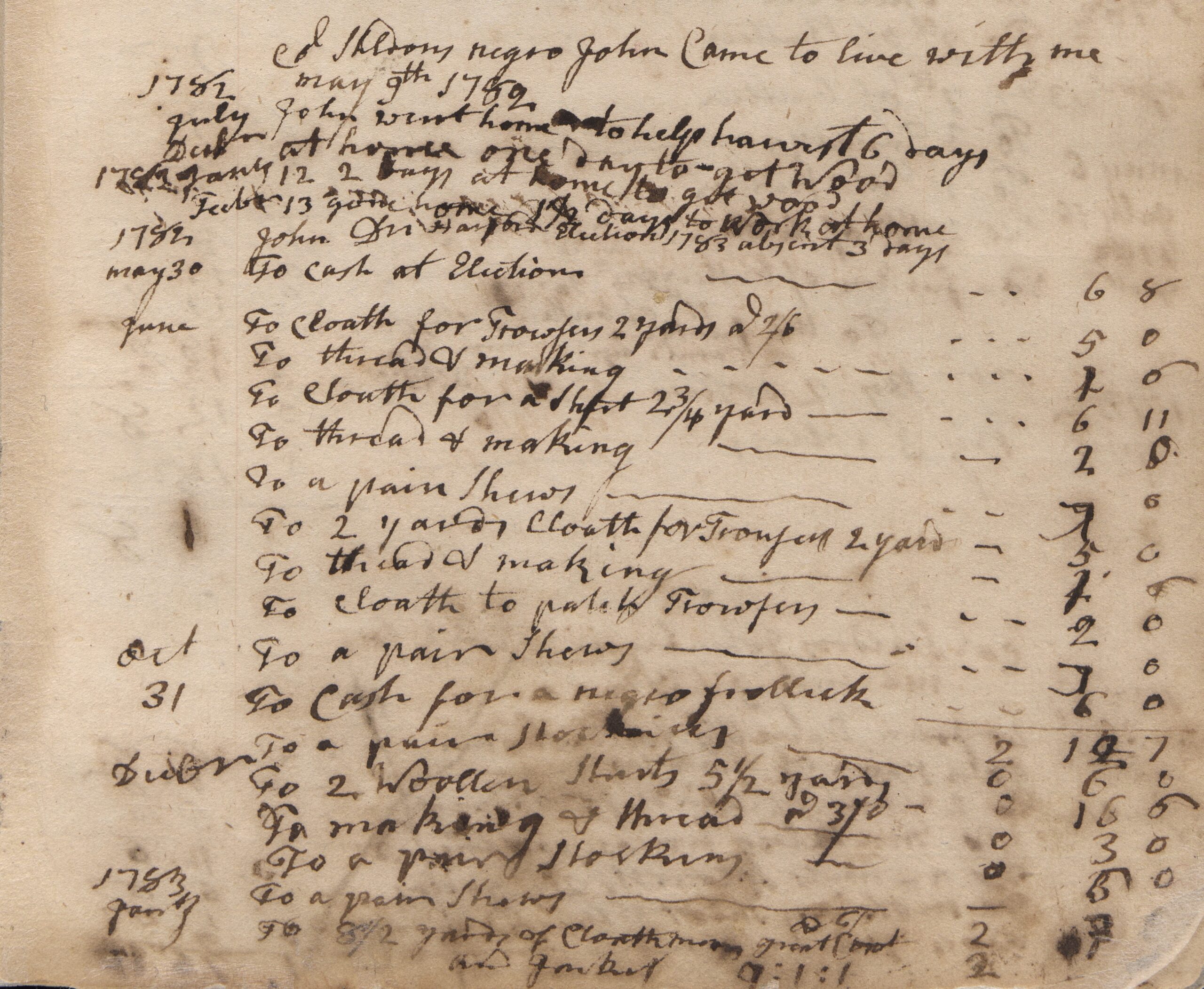

For the biography of John Sheldon, see: Ashley Account Book 1, 291, 295–6; , Ashley Account Book 2, 45; Ashley Account Book 3, 128–9; Ashley Account Book 7, 66; Drew, If They Close the Door on You, 48; Sheffield, Massachusetts Assessor’s Tax Lists and Records, years 1798, 1799, 1800, 1801, and 1802; “John Ashley, Esq., Sheffield 1802 (Record no. 2195),” NEHS, 5; Ashley Account Book 12, 108.

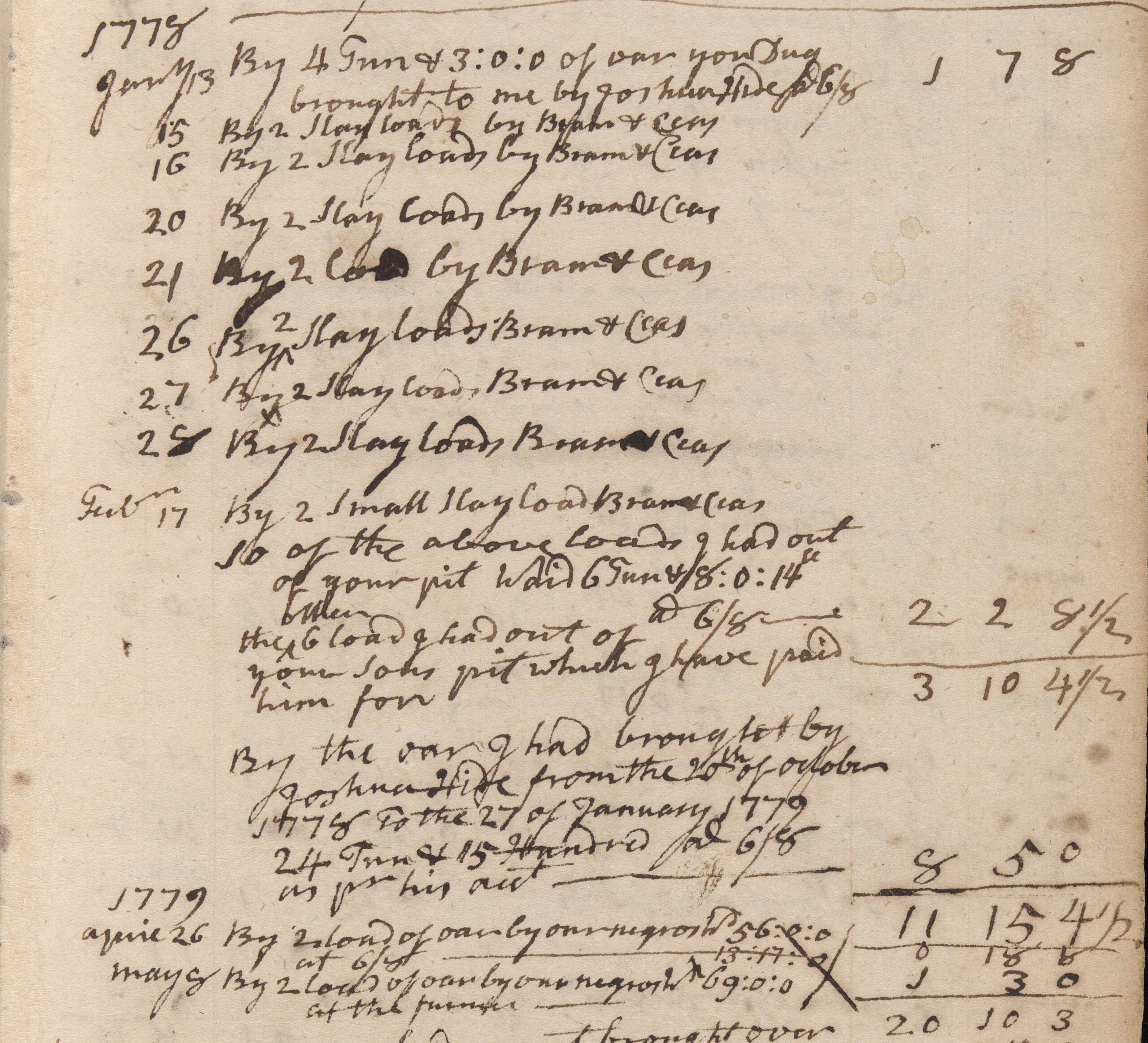

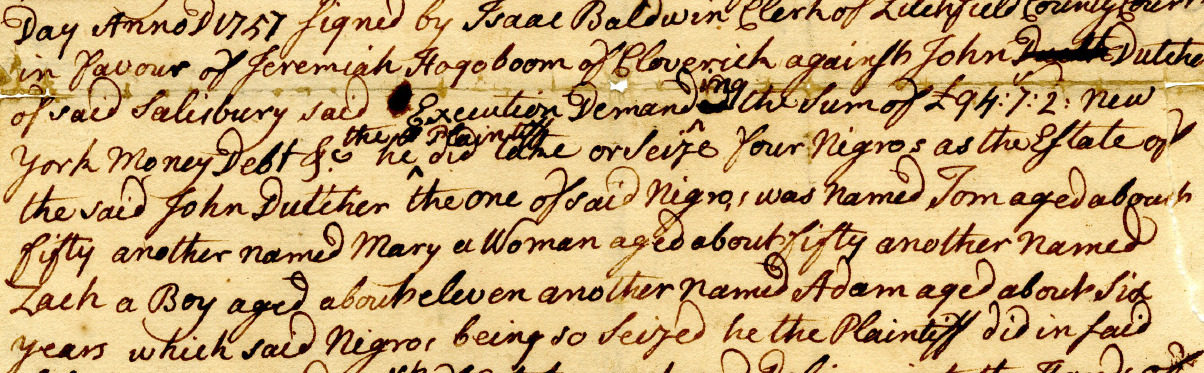

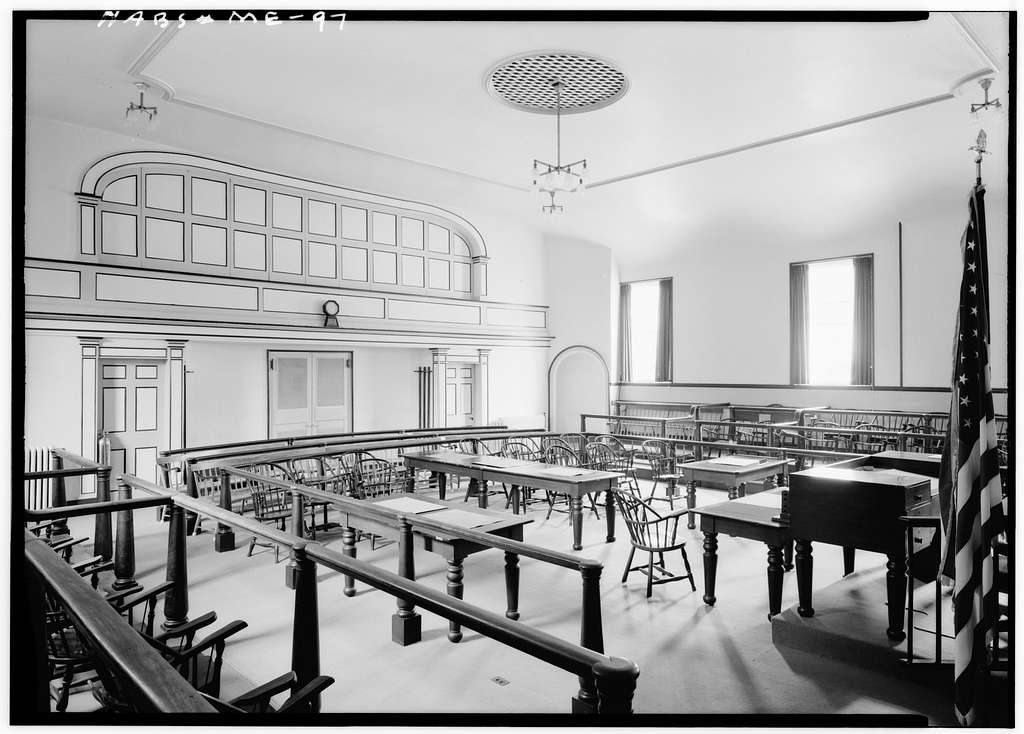

For the biography of Adam Mullen, see: “Attachment, 1757 Dec 8,” Litchfield Historical Society, Wolcott Family Collection: Miscellany, Connecticut County Court (Litchfield County), 1753-1757, Folder 9, Item 4; Ashley Account Book 1, 237, 245, 281; Sheffield, Massachusetts Assessor’s Tax Lists and Records, year 1781; “Adam Mullen, to Samuel Bellows Sheldon, January 30, 1786, vol. 24, (Massachusetts Land Records 1620-1986: Southern Berkshire Registry of Deeds), 263; Col. J. Ashley, “Account regarding work of “Adam” for John Ashley”; “Entry for Jacob Mullen,” U.S. Census, 1810, 1820, Pittsfield, Massachusetts; Ashley Account Book 3, 18, 26; Ashley Account Book 11, 291; Ashley Account Book 15, 299; “Jared Canfield vs. Adam Mullen,” April 18, 1803, case no. 95, Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas records, 1760–1860, vol. 20, 401–2; “Ziba Bush vs. Adam Mullen,” April 1807, case no. 233, 1809, Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas records, 1760–1860, vol. 27, 61–2; “Philander Hurlburt vs. Elisha Smith,” January 4, 1808, case no. 195, Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas records, 1760–1860, vol. 24, 13; Asahel Olds, to John W. Hurlbert, September 21, 1807, vol. 46, (Massachusetts Land Records 1620-1986: Southern Berkshire Registry of Deeds), 83; “William Bull vs. Adam Mullen,” March 16, 1810, case no. 368, Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas records, 1760–1860, vol. 27, 373–4.

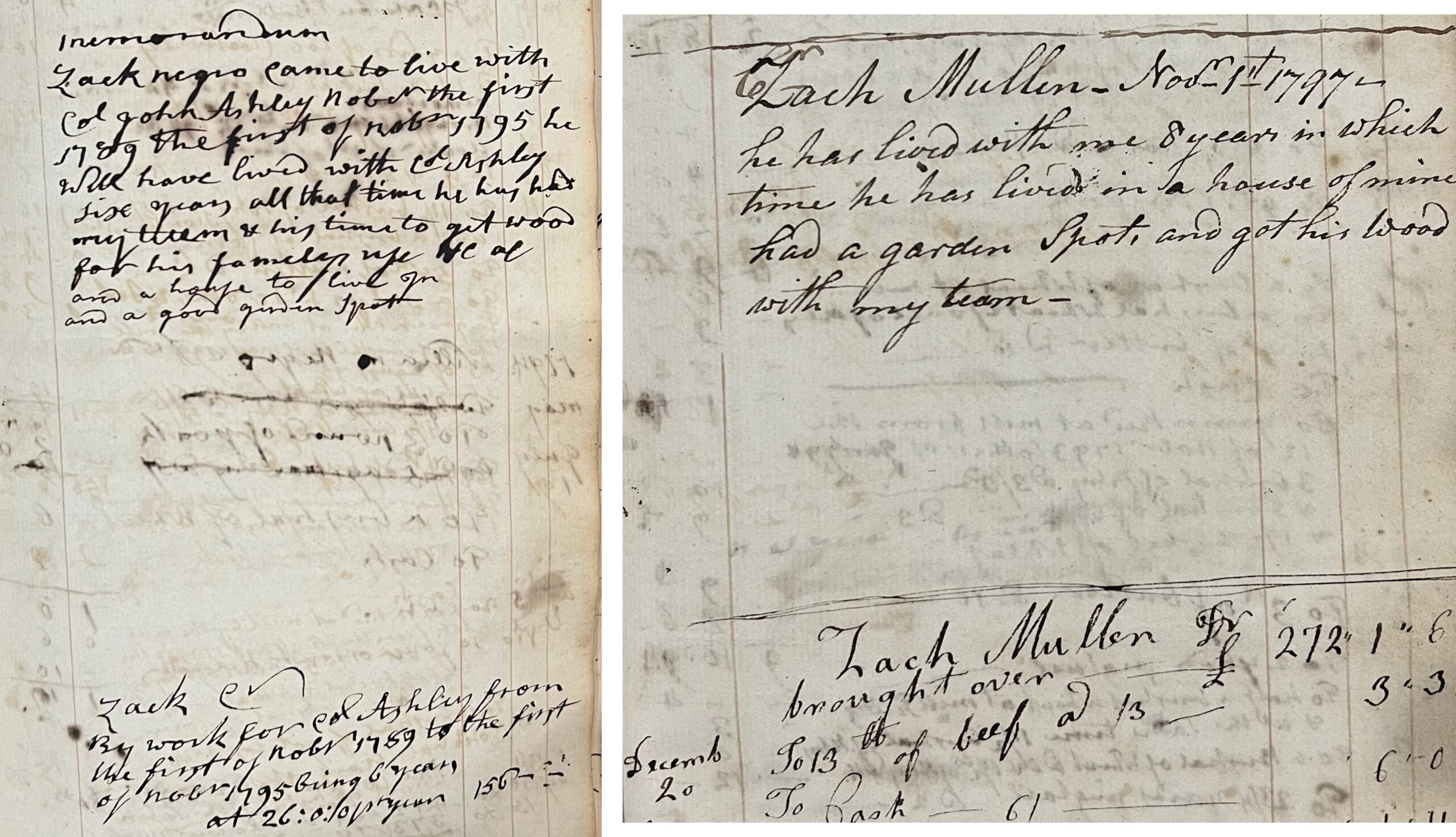

For the biography of Zach Mullen, see Adam Mullen as well as “Zach Mullen vs. John Ashley Esq.,” April 1781, case no. 20, Berkshire County, Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas records, 1760–1860, vol. 4, 24; Sheffield, Massachusetts Assessor’s Tax Lists and Records, year 1781, 1784, 1785, 1788, 1789, 1798, 1799, and 1800; Ashley Account Book 3, 60, 77, 91, 109, 111, 119, 126; Colonel John Ashley, “Account regarding work of “Zach” for John Ashley,” 1787-1789, loose note, Ashley Family Genealogy Files, collection of the Sheffield Historical Society, box 2; “John Ashley, Esq., Sheffield 1802 (Record no. 2195),” NEHS, 5, 78; “Entry for Zacheus Mullen,” U.S. Census, 1790, Sheffield, Massachusetts; Ashley Account Book 11, 246; Ashley Account Book 2, 87, 94 –5, 101, 217–8; Ashley Account Book 12, 26; Ashley Account Book 18, 95.

Zach Mullen’s son-in-law also resided with the family in 1795. Moreover, a man named Elijah Mullen (ab. 1784–1860) was born around 1783 in Sheffield to either Zach Mullen or his brother Adam Mullen. Elijah Mullen had a household of four people in Sheffield in 1810, possibly including Zach Mullen. By the 1820 federal census, he had moved to Pittsfield.

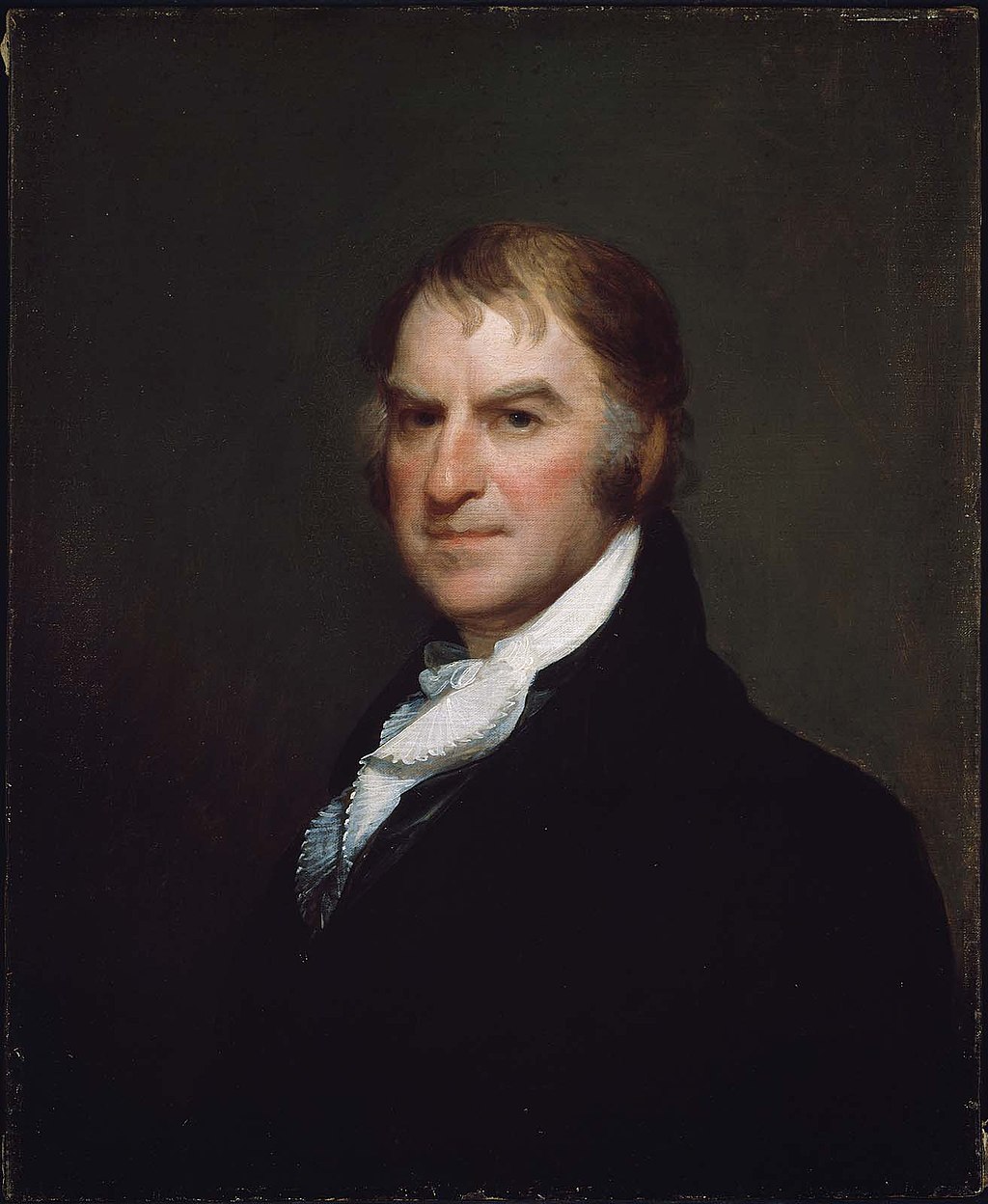

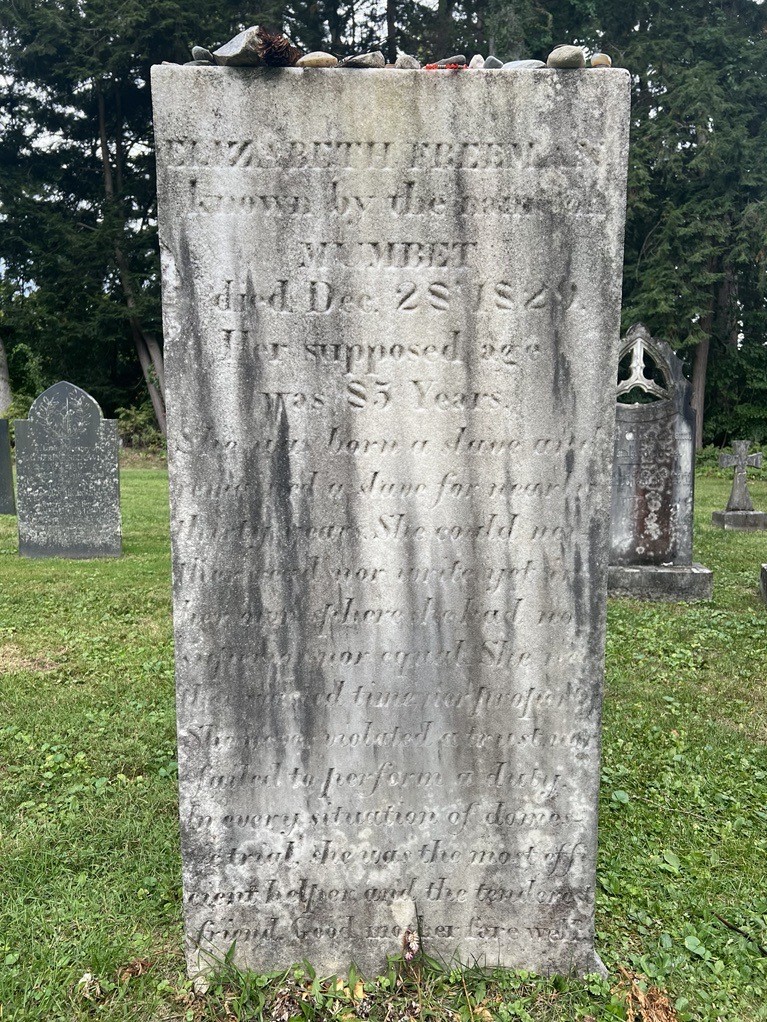

For background on the Elizabeth Freeman, see Piper and David Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman; Sari Edelstein, “‘Good Mother, Farewell’: Elizabeth Freeman’s Silence and the Stories of Mumbet,” The New England Quarterly 92, no. 4 (November 1, 2019): 604, 611; Arthur Zilversmit, “Mumbet: Folklore and Fact,” Berkshire History 1, no. 1 (Spring 1971): 5–6.

For the biography of Elizabeth Freeman, see: Theodore Sedgwick, Jr., The Practicability of the Abolition of Slavery: A Lecture, Delivered at the Lyceum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, February, 1831 (New York, NY: Printed by J. Seymour, 1831), 14, 16; Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, vol. 2, 3 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), 104; Elizabeth Freeman, Stockbridge, 1830 (Record no. 4959),” in Berkshire County, MA: File Papers, 1761–1917, vol. 1: Berkshire Cases 4000 –5999, 4; Catharine Maria Sedgwick, “Slavery in New England,” Bentley’s Miscellany, 1853, Vol. 34, 419; Piper and Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman, 63; Beth Luey, “”One Minute’s Freedom”: The Colonel John Ashley House, Sheffield,” in At Home: Historic Houses of Central and Western Massachusetts, Bright Leaf (Amherst, MA: Bright Leaf, 2019), 47; Hardy, “Mum Bet vs. Ashley,” 2–3; Elizabeth Freeman and Jonah Humphrey, to Enoch Humphrey, April 1, 1809, vol. 47 (Massachusetts Land Records 1620-1986: Southern Berkshire Registry of Deeds), 751–2; Enoch Humphrey, to Elizabeth Freeman and Jonah Humphrey, April 1, 1809, vol. 47 (Massachusetts Land Records 1620-1986: Southern Berkshire Registry of Deeds), 233–4.

If sister Lizzie was a real person enslaved in the Ashley House, a possible explanation for her not joining the Sedgwick household could be that she was already married and opted to stay with her spouse in Sheffield. Most of the wives’ names of the enslaved men in the Ashley household are unknown; Ashley Account Book 1, 43, 93; “Elizabeth Freeman, Stockbridge 1830 (Record no. 4959),” NEHS, 4; Felicia Y. Thomas, “‘Fit for Town or Country’: Black Women and Work in Colonial Massachusetts,” The Journal of African American History 105, no. 2 (March 2020): 204–6; Brom & Bett vs. J. Ashley Esq, 1781; Piper and Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman, 118.

For the biography of Betsey Freeman, see: “Entry for Betsey Humphrey,” U.S. Census, 1850, Lenox, Massachusetts; “Entry for Betsey Humphrey,” U.S. Census, 1855, Lenox, Massachusetts; “Entry for Betsey Humphrey,” April 21, 1858, Deaths Registered in Lenox 1858; Piper and Levinson, One Minute a Free Woman, 133, 137–9, 157; Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Life and Letters of Catharine M. Sedgwick, ed. Mary E. Dewey (New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1871), 73, 327.

For the biography of Mary, see: “Indenture in two parts between J. Ashley and Mary,” 1789, Sedgwick Family Papers, 1717-1946: miscellaneous manuscripts (Theodore Sedgwick), bound ed., collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; Melish, Disowning Slavery, 96–7; Ashley Account Book 3, 134.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to my curatorial and archives team at The Trustees of Reservations and the Sheffield Historical Society for supporting and encouraging this deep exploration. Thanks to the Connecticut State Museum, Great Barrington Historical Society, Litchfield Historical Society, Massachusetts Historical Society, Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge Library, Museum & Archives, and UMass Amherst W.E.B. DuBois Library for their assistance and for opening their archives to me. The three Ashley family account books stewarded by The Trustees and the Col. Ashley House historic photograph collection were recently digitized thanks to a grant by the National Endowment for the Humanities. This research was made possible by support from the Decorative Arts Trust in their sponsorship of a Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Fellowship at The Trustees.

This article originally appeared in January 2025

Olivia R. Scott (Livy) is the Decorative Arts Trust Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Fellow with The Trustees of Reservations at the Colonel John Ashley House. This work marks the first of more forthcoming research into the enslaved population of the Berkshires and the reinterpretation of the Col. Ashley House and its historic interiors.