Mohawks, Mohocks, Hawkubites, Whatever

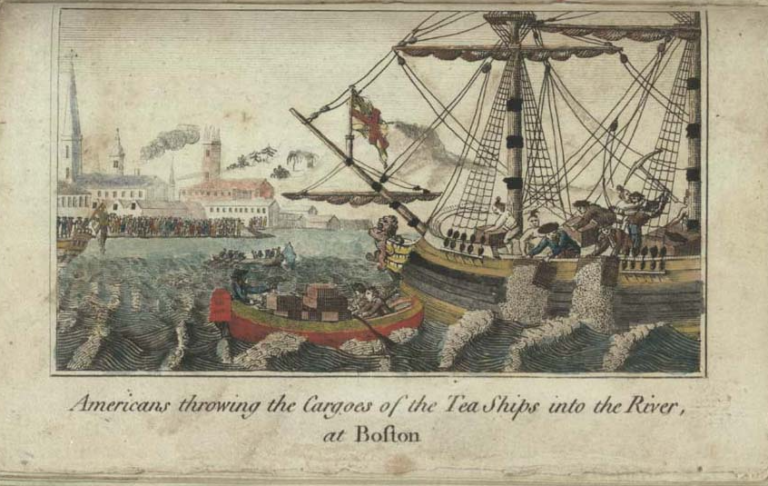

The stealthy invaders who dumped the tea on the night of December 16, 1773, “were mostly disguised as Indians…with no more than a dab of paint and with an old blanket wrapped about them…The reason why they dressed this way and called themselves Mohawks is unknown”—this according to Benjamin Labaree in his masterful study The Boston Tea Party. Perhaps the answer can be found in the legendary night scare figures called the Mohocks, who, in gangs, were purported to roam the streets of London early in the eighteenth century.

There is little evidence that the Bostonians called themselves Mohawks before the big tea dump, though a decision had clearly been made that their disguise would be as “Indians.” “Indian,” like “Turk,” “Moor,” and “The Green Man” were terms given bogie men and night dwelling maskers throughout the Anglophone world.

The so-called mobbing had been carefully planned, the participants chosen, and the disguise agreed upon. Those chosen to be Indians were instructed to clothe themselves with old blankets and to black their faces. George Twelve Hewes, one of the participants, wrote that with only “a few hours warning of what was intended to be done” they hastily costumed themselves, smearing their faces and hands “with coal dust in the shop of blacksmith.” Secrecy and silence became the order of the evening. Even though they were representatives of the suitably angry political factions incensed by the tea tax and the patronizing treatment of the British authorities, the tribe proceeded in amazingly orderly and quiet fashion. There were three ships to be boarded and three groups of blanketed figures carrying hatchets, hoes, or whatever other tool came to hand. Each “division” had a “commander” according to Hewes; indeed he was the one appointed to deal with the captains of the ships and to gather the keys to the storerooms so that they might proceed in a quiet and orderly fashion. Hewes remembered that immediately after the event the raiders “quietly retired” to their “several places of residence…without having any conversation with each other, or taking any measure to discover who were our associates.”

The Loyalist Peter Oliver in his not unbiased account of the proceedings noticed, “There was a Gallery at a Corner of the Assembly Room where Otis, Adams, Hawley & the rest of the Cabal used to crowd their Mohawks & Hawkubites, to echo the oppositional Vociferations, to the Rabble without the doors.” Written from London eight years later, Oliver’s notes accurately reflect the Tory talk surrounding the Boston troubles, and “Mohawks and Hawkubites” seem to refer to the tea party participants.

But these terms were far from new. They came into use at the spectacular and unexpected arrival of four Mohawk “ambassadors” to the court of Queen Anne in 1712. Generally called “kings” or “sachems” only three of them were actually Mohawks—the fourth being a Mohican—and none of them were regarded as leaders. They were encountered by many Londoners, not only those who officially received them at court. They went to all of the best tourist locations, dined well though they were eating foods that were far from their usual diets. Wherever they ventured, they created a traffic jam.

After this visit, the word Mohawk took on a life of its own. Rumors began to spread that a night-marauding group of the Hellfire sort made up of young swells called “Mohocks and Hawkubites” was engaged in night raids on unsuspecting folks who wandered into their clutches. They were said to be a secret group of bucks and blades who had taken blood oaths as part of a membership ritual. They marked their victims by slitting their noses with knives or by placing them in a barrel and rolling them down hill. There is no evidence that the group actually existed, but many specific incidents were attributed to its members. If it did exist, it was probably one of many secret societies that existed in the shadows of the men’s club culture that flourished in eighteenth-century London.

Rumors of the depradations of this group coursed through London, creating the Mohock Scare of 1712-13. A play about them was published, though never acted, called The Mohocks, probably by John Gay, later famous as the author of The Beggar’s Opera. Richard Steele in The Spectator of March 10, 1712, refers to them as “that species of being who have lately erected themselves into a nocturnal fraternity under the title of the Mohock Club.” Just how mysterious were the organization, its costume, and its activities becomes clear in Steele’s report: he thought them “East Indians, a sort of cannibals in India, who subsist by plundering and devouring all the nations about them. The president is styled Emperor of the Mohocks, and his arms are a Turkish crescent.” Jonathan Swift wrote to his friend “Stella” (Esther Johnson), asking, “Did I tell you of a race of rakes, called the Mohocks that play the devil about this town every night, slit people’s noses, and beat them…Young Davenant was…set upon by the Mohocks,…they ran his chair through with a sword.”

The Boston tea riot was tied to the boisterous operations of such male voluntary associations, though hardly of the elite sort found in London. Such groups seemed to emerge as an outgrowth of commercial life throughout Europe and especially the British colonies. Philadelphia, Boston, Annapolis, and Charleston were proud of the fact that their level of civility was exhibited in the number of different clubs that had been formed. Most of them were urban clubs run by and for the urban elite, but they were found in frontier towns as well, sometimes constructing one of the first solid buildings as their lodges.

When the aggravation over the tea tax developed organized momentum it arose from a town-meeting style gathering at Faneuil Hall. When it became clear that there were interested parties from beyond the boundaries of Boston, the proceedings were moved to the Old South Meeting House a few blocks away (and somewhat closer to Griffin’s Wharf, where the ships were berthed). Now constituted as “The Body,” all of those who crowded into the building were given voice and vote. Just who was attending is unclear, and their number is disputed; but it was near the winter solstice, the long time of the year, when workers in the countryside took time off from their everyday, every-year tasks to visit the city, and farmers from outlying areas probably joined Boston artisans in this voluntary and spontaneous assembly. The speeches of Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and others assembled at the meeting house went well into the dark and drizzly evening. The cover of dark was sufficient to protect the identities of the rioters from discovery. The taking on of disguises simply amplified the spirit of common purpose and celebration.

The Boston incident, far from being unique, illustrates the long-standing importance and familiarity of what are commonly depicted as spontaneous mob actions.

More commonly found in the face-off between frontiersmen and landowners, White Indian groups were to be found in renter or squatter communities throughout the colonies, such as Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain boys who “played on popular images of wilderness disorder.” The tea situation was greeted with an uproar in many ports, not only Boston. But in that clubbable city, the troubles operated like a magnet, bringing thousands of men to the wharves from various areas, including the colonial backcountry. The Boston incident, in other words, far from being unique, illustrates the long-standing importance and familiarity of what are commonly depicted as spontaneous mob actions. It also illustrates the fact that, whether real or imaginary, discussions of—and rumors concerning the doings of—”Mohawks,” “Mohocks,” and “Hawkubites” had been a part of ordinary peoples’ lives for decades before that fateful December night in 1773.

The best book on the tea party remains Benjamin Labaree, The Boston Tea Party (Oxford, 1964). Hewes’s quotation I take from Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston, 1999). For events of the structure of mob activity in Boston, see Bob St. George’s Conversing by Signs: Poetics of Implication in Colonial New England Culture (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1998) in which various forms of house attack are detailed. The visit of the four kings is described in Richmond Pugh Bond, Queen Anne’s American Kings (Oxford, 1952). The famed court portraits can be seen at Wikipedia. See also Eric Hinderaker, “‘The Four Indians’ and the Imaginative Construction of the First British Empire,” William and Mary Quarterly 53:3 (July 1996). The most important documents of the Mohock Scare are detailed in Neil Guthrie’s “‘No Truth or very Little in the Whole Story’—A Reassessment of the Mohawk Scare of 1712,” Eighteenth Century Life 20:2 (1996): 33-56. The key documents on the scare are best accessed through the guide to the papers of Ernest Lewis Gay, 1874-1916, collector: “Papers concerning the Mohocks and Hawkubites”: Houghton Library, Harvard College Library. Peter Oliver’s comments may be found in Douglass Adair and John A. Schutz, eds., Peter Oliver’s Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View (Stanford, Calif., 1961). This document provides an anatomy of abuses as employed by Tories on both sides of the Atlantic. I survey the white Indian literature in “Introduction: A Folklore Perspective,” in William Pencak, Matthew Dennis, and Simon P. Newman, eds., Riot and Revelry in Early America (University Park, Pa., 2002).

This article originally appeared in issue 8.4 (July, 2008).

Roger D. Abrahams is the Hum Rosen Professor of Folklore and Folklife emeritus, University of Pennsylvania. His books include The Man-of-Words in the West Indies (1983) and Singing the Master (1993) and, most recently, Blues for New Orleans, coauthored with Nick Spitzer, John Szwed, and Robert Farris Thompson (2005). His research interests and publications include reports of historical and contemporary masking and mumming in North America and the Greater Caribbean.

“Whenever the pillars of Christianity shall be overthrown, our present republican forms of government, and all the blessings which flow from them, must fall with them.” These were the words of Jedidiah Morse, preached before a Massachusetts congregation in 1799. It is hard to find language that is more histrionic in the American religio-political landscape. At first glance, Morse’s statement clearly reflected the confusion and anxiety that coalesced around the concepts of religion, secularization, Christianity, clerical authority, Protestantism, atheism, government, partisan politics, and international affairs in the last decade of the eighteenth century. It is therefore easy to view Morse’s shrillness simply as a symptom of changing times, specifically of the rapid and well-known process of disestablishment in the early republic. But I would like to come to Morse not from his own era, but from the one that preceded it, the American Revolution. From that vantage point, Morse’s words are a bit more puzzling, and I’d like to suggest that they can prompt new methodological and chronological questions, not just about the 1790s, but also about the Age of Revolution. In short, what had really changed to make Morse so nervous, and when was it?

This question ultimately derives from the difficulty of connecting the historiography of religion in the early republic to that of religion during the revolutionary era, as well as to theoretical work on the development of the “secular” across a roughly similar time period. Jedidiah Morse is the center of this inquiry because, as an alarmist and a controversialist, he loudly announced a moment of crisis through his sermons on the Bavarian Illuminati, a particularly hysterical episode in the religio-politics of the early republic. He has also been showing up like a bad penny in my research into this period, suggesting that he might be an effective figure through which to think about the questions suggested above. The Illuminati were a dreaded but nonexistent group of powerful atheists that Morse, Timothy Dwight, and some fellow Federalists feared were conspiring to undermine Christian institutions, as evidenced both by the dangerous turn of the French Revolution and also by the decline of respect for traditional clerical authority in the United States. At its height in the 1790s, this moment of conspiracy-theory panic may have been of short duration, but Morse did live in an era of great transition, and his expressions of anxiety are revealing.

In an effort to understand the relationship between the historical course of the American Revolution and the transformation of “religion” in the same period, this essay draws attention to two very different kinds of historical ruptures evident in Morse’s writings in the 1790s. The first break involves division within the intellectual, cultural, social and political realm of religion, leading to the emergence of the religious and the secular as separate intellectual categories. The second rift is chronological: the upheaval caused by the political events of the American Revolution, a historical transformation so comprehensive (we often assume) that historians of all arenas are forced to question how, rather than if, their subjects experienced the change. In other words, it is a period where change, rather than continuity, was the norm.

The question, ultimately, is whether, and in what ways, should we follow Morse’s lead by disconnecting the threats to religion from historical events before 1790?

In 1798 and 1799 Morse believed that his religion, a public and Protestant form of that concept in which he enjoyed a privileged position, was endangered by events in the civil realm that threatened the new nation of the United States. Identifying that threat meant operating within a very new historical moment. Though the Federalist clergy had overwhelmingly embraced the legitimacy of the new nation, as Morse reminded his readers, historians will note that when he connected the foundations of his “religion” to the institutions of the United States, he did not connect them to, for example, the Protestantism that had animated the British empire of his youth, to an evangelical Kingdom of God, or even to Massachusetts, all of which, in different contexts, were viable religio-political constructs during the late colonial and revolutionary periods of his youth. When Morse linked the foundations of his religion to a government that was only a decade old, he distracted attention from the political events of the preceding era and from polities other than the United States. His political posturing thus served to situate his anxieties in a remarkably short time frame. What happened before 1790 stayed before 1790, as it were. The question, ultimately, is whether, and in what ways, should we follow Morse’s lead by disconnecting the threats to religion from historical events before 1790?

I will ask this question in three stages. First, it is necessary to locate what Morse meant when he discussed religion, a phenomenon he identified largely in terms of its public manifestations. Second, I will look at what threats he identified to his religion. Both of these discussions focus, as one would expect, on the 1790s. In the third section below, I seek to place the Illuminati controversy and the religion in the 1790s in a wider context, and finally return to the question at hand—what do religion and politics in the 1790s have to do with the American Revolution?

Most historians know Morse for his widely circulated geographies and for the activities of his even more famous son, artist and telegrapher Samuel F. B. Morse. Jedidiah was born in Woodstock, Connecticut, in 1761, in the waning days of the Seven Years’ War. He came of age in the midst of the Revolutionary War. Too infirm to serve in the defining conflict of his youth, he spent the war years in New Haven, and he studied with Jonathan Edwards, fils. By all accounts, as a young man he was not particularly drawn to the theological questions that animated his New Divinity peers. Thus, after graduation he worked and traveled for a few years as an adjunct scholar and minister, and it was during this time that he researched and wrote his American Geography, the genre (in a variety of forms and editions) for which he became most known. On his travels he made the most of the clerical and political networks to which his position as a member of the religio-intellectual elite gave him access. He finally took up a pulpit in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1789, a prominent post from which he both lamented and hastened (through his anti-Unitarian machinations) the decline of New England’s “Standing Order” over the next several decades. He later published more geographies, histories, periodicals, and a few sermons, and he helped found some of the major religious reform societies of the day, including the American Bible Society. But he never held major office or ascended to the upper echelons of literary fame, and by all accounts his shrill and contentious personality limited his influence.

Though Morse did not rise to the pinnacles of the intellectual, theological, or political elites of his day, his writings are still widely cited in a variety of contexts. His polemics, his role as a historian (for which he corresponded with figures such as John Adams), and his contributions to the project of crafting national identity through his geographies have made his corpus of work a useful source for understanding cultural and intellectual trends in the early republic. In addition, Morse is also something of a darling of the twenty-first century Christian political right. In those circles, he is sometimes a “Founding Father” and sometimes an important historical observer of the nation’s birth. Christian nationalist David Barton has numerous references to Morse on his Wallbuilders website, and quotations from his sermons continue to circulate in ways that suggest the enduring importance of the anxiety about religion in the United States that he articulated. Morse was, these modern interpreters suggest, a witness to history, a well-qualified observer of a moment of greatness, as well as someone who issued an early clarion call to the citizens of the nation for the essential and foundational role of religion in government. Morse noticed great change around him.

Academic historians have agreed with at least that assessment: something was rapidly changing about what Morse referred to as religion in the 1790s and in the early modern era more generally. My discomfort with this paradigm comes not from any essential disagreement with historical assessments of the Illuminati event, but with the relationship of this micro-moment of pivotal change in the category of religion (the 1790s) to that which came before it, the period of the Revolutionary War. Before turning to that subject, however, we should know what Morse referred to as religion. This matters because if we are slippery about what we mean by a term as amorphous as “religious decline,” we can easily lose our capacity to locate cause and effect. Religious decline in a vague sense can be seen merely because something new is on the scene, a new mode of intellectual inquiry, or a new political system. But the arrival of something new does not always signal the decline of something old. To see the decline of religion, we have to know what religion (in a particular given context) is.

In his 1799 Illuminati sermon, Morse built a workable, clergy-driven (and defined) iteration of a public institution that he called “religion.” The religion he discussed had little to do with the individual soul or personal spiritual experience. In the context of the Illuminati, Morse was primarily concerned with religion as an institutional, cultural, and political system. He started from his text, Psalm 11, verse 3: “If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?” He then made the assertion that the nation’s “dangers are of two kinds, those which affect our religion, and those which affect our government.” The two are “so closely allied,” he explained, “that they cannot, with propriety, be separated.” Religion (he slipped quickly to the more precise “Christianity”) and governmental stability were, for Morse, integrally linked. Christianity, he went on to explain, provided the “kindly influence” requisite for “that degree of civil freedom, and political and social happiness which mankind now enjoy.” He continued:

In proportion as the genuine effects of Christianity are diminished in any nation, either through unbelief, or the corruption of its doctrines, or the neglect of its institutions; in the same proportion will the people of that nation recede from the blessings of genuine freedom, and approximate the miseries of complete despotism. I hold this to be a truth confirmed by experience. If so, it follows, that all efforts made to destroy the foundations of our holy religion, ultimately tend to the subversion of our political freedom and happiness. Whenever the pillars of Christianity shall be overthrown, our present republican forms of government, and all the blessings which flow from them, must fall with them.

In this rendering, the “pillars of Christianity,” according to Morse’s statement, were belief, pure doctrines, and attention to the institutions of Christianity (presumably churches, sacraments, public worship, and the clergy). This, according to Morse, was the “holy religion” that the nation must protect.

For many purposes, it would be reductionist to define “religion” as public versions of belief, doctrine, and institutions, but the definition is a useful one for this context—that articulated by a Protestant minister in a fast day sermon in an established church at the tail end of the eighteenth century. Moreover, each of the elements Morse articulated was, from the perspective of the clergy, quite expansive. Belief, the opposite of unbelief, was not merely the intellectual predilection of an individual or even many individuals, as it might be in a modern, secular world, but rather the broad-based piety of the populace, the presumption that a divine order was paramount and true. Doctrine, the second element, was probably the easiest of the three for clergy to define and endorse, as it was the one that they had historically had the most control over. By including it in the list, Morse implicitly asserted the importance of theological education and the possibility that corrupted doctrine would not be considered religion. This let him exclude, for example, any non-Protestant religion, be that Catholicism or the superstitious practices of native peoples, as well as any Protestants whose doctrine he thought had slipped too far. It was a category that enhanced his own authority. Thus, though he recognized and used the intellectually expansive word “religion” in some contexts, in the world around him the government and freedom for which he advocated relied on an institutional Protestantism overseen by an educated clergy capable of adjudicating doctrine and acceptable boundaries of dissent.

Most important, Morse referred to the institutions of religion. This included both the apparatus of clergy and congregation, and also the presence of the clergy on the public, political stage. It included, for example, the events at which he preached about the Illuminati. President John Adams had called for a fast day a few weeks before the 1798 sermon, asking the nation to spend the day in “solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer” because “the United States of America are at present placed in a hazardous and afflictive situation by the unfriendly disposition, conduct, and demands of a foreign power,” and thus “the duty of imploring the mercy and benediction of Heaven on our country demands at this time a special attention from its inhabitants.” Public sermons on nationally ordained fast days were an important ritual of institutional Christianity in the early modern era. Occasional sermons, those preached at such events, represented an agreement between established clergy and the government that at pivotal moments, the population should pause to reflect on its situation in the divine order. The most widely quoted sermons of the Revolutionary period, such as Ezra Stiles’s “The United States Elevated,” and John Witherspoon’s “Dominion of Providence,” were preached at these rituals of mutual endorsement between the institutions of Christianity and the state. Morse’s sermon thus stood in a long tradition of political preaching. The 1798 sermon’s text was a blend of familiar tropes in addition to its outcry for defense against the Illuminati, such as a lament for the general state of present affairs, a call for greater piety, devotion, and unity in a time of national crisis.

The public practice of Protestantism—like any institutional system—required significant resources, both in terms of physical buildings and personnel, and this system was, to read Morse, on the defensive in 1798. One can presume here that Morse referred to the health of those institutions as a core part of “religion.” If public worship were neglected, if clergy were not respected as natural moral, political, and intellectual leaders, or if churches were not a part of the infrastructure of towns, the laity, even those who resisted unbelief, would have no regular opportunity to engage “religion,” by hearing sermons preached by an educated clergy in a sacred time and space. “If the Clergy fall,” he asked in 1798, “what will become of your religious institutions? Undoubtedly they must share the same fate. And are they of no value?” Indeed one of the greatest threats of the Illuminati, as he articulated it again in 1799, was to the clergy, as the devious French interlopers were engaged in “apparently systematic endeavours made to destroy, not only the influence and support, but the official existence of the Clergy.”

Morse’s definition of religion was fairly conventional for his moment, particularly from the perspective of the clergy and the government. It encompassed formal Protestantism; it admitted acceptable division among denominations about such questions as religious experience, the sacraments, and salvation; and it excluded anything the clergy determined to be corrupted. It was the religion that framers of the Constitution principally imagined when they thought of both religion and establishments. It was the religion that skeptics decried as “priestcraft.” This is the version of religion Morse believed to be in decline in his day.

If we accept, for sake of argument, what Morse meant when he discussed religion, and also the idea that the 1790s was an era of intense religious redefinition, the next task is to sort out why, both in Morse’s view and in the view of scholars today. My main concern, as mentioned above, is chronological: what relationship did Morse (and his interpreters) perceive between the decline of Morse’s form of religion and the American Revolution, the phase of dramatic political change that preceded the 1790s? To start with Morse, he discussed two main threats: 1) attacks on the clergy, such as threats to the public support they received and attempts to thwart them in their duty to speak to public issues, and 2) the great danger of unbelief. The first cause has obvious ties to the historical moment of Morse’s writing in the political process of disestablishment, and he referenced that process. The first amendment of 1791 guaranteed that there would be no federal establishment; most colonial establishments had been already been eliminated; and of the states without origins as British colonies, only Vermont created a religious establishment, and it did not long survive. The establishments in Connecticut and Massachusetts were facing increasing scrutiny, and the complex system that sustained the Standing Order faced a series of legal challenges that led to its dismantling. That this process was not concluded until well into the nineteenth century does not mean that ministers like Morse did not resist its progress. In the heat of the Illuminati crisis, however, Morse did not blame the problems on the American political system, for which he protested his profound support, or even on the American Revolution, but rather to a backlash caused by the clergy’s opposition to the French.

Even beyond the attacks on institutional religion, irreligion—unbelief in Morse’s terms—was the great threat to “religion” in the last years of the eighteenth century, and France was to blame. In the May 1798 sermon, Morse drew a connection between the words of his biblical text, “This is a day of troubling, or reviling, and blasphemy. Wherefore lift up thy prayer for the remnant that are left,” and Adams’s words in declaring the fast, the “hazardous and afflictive situation.” He articulated the parallels between the trials of King Hezekiah with the Assyrians, on the one hand, and the perilous situation the Americans then faced with the French. Morse then mixed the dangers from abroad with dangers at home. “The astonishing increase of irreligion” that he perceived around him also harkened back to his text, as it pointed to a day of “blasphemy.” Helpfully, Morse explained what he meant by “irreligion.” “I use this word in a comprehensive sense, and would be understood to mean by it, contempt of all religion and moral obligation, impiety, and everything that opposeth itself to pure Christianity.” The irreligion, “disorganizing opinions, and that atheistical philosophy” that had started in Europe had spread. “To this plan,” Morse wrote, “as to its source, we may trace that torrent of irreligion and abuse of every thing good and praise-worthy, which, at the present time, threatens to overwhelm the world.” The overall argument of the Illuminati sermons was an outcry over the terrible events unfolding in Revolutionary France, their spread to the United States through the “plan” of the Illuminati, and the resulting decline of “religion” in what could have been a great nation. The agent of these changes was the insidious conspiracy.

As he articulated his conspiracy theory, Morse explained religious change through the political, historical process, and he did so in a very short time frame, the same post-revolutionary framework that included the process of disestablishment. In short, the 1790s. When he blamed the “secret societies under the direction of France” that were endangering the fabric of American society, he suggested the core institutions of his society were in the hands of human, political actors. For example, the Illuminati did their damage through false diplomacy—attempting to raise a black army in St. Domingo that would attempt to foment slave revolt in the South, for example—and also through the more banal crimes of encouraging disrespect and dissent against the Godly rulers of the United States. It is significant that the threat was being furthered by “subtil and secret assistants” who were “increasing in number,” and “multiplying, varying, and arranging their means of attack,” because the largely unseen danger required Morse, as an important representative of public “religion,” to raise the alarm, and also because the danger might result in threats in myriad unknown places, such as in newspaper attacks on Adams, or in democratic societies that advocated for the United States to support the French. The damage had already begun. In addition to the persistent attacks on the place of the clergy, Morse ascribed the “unceasing abuse of our wise and faithful rulers; the virulent opposition to some of the laws of our country, and the measures of the Supreme Executive,” and the Whiskey Rebellion to the machinations of the insidious agitators.

Historians, those practiced in the careful art of teasing out change over time, have largely concurred with Morse in his chronological framing, if not in his assessment of the threat posed by the Illuminati. Unfortunately, this tacit acceptance has begged an important question about precisely how the Revolution shaped religion, whether one refers to Morse’s public Protestantism or to a different version of the phenomenon then viable in the public discourse. The essence of the problem, historically, reads like a GRE logic problem. Only one of the following should be true: 1) If the decline in religion Morse perceived was real, and it came from causes outside of the realm of religion, those causes—presumably occurring in the preceding decades or centuries—and their impact should be identifiable. If we cannot identify the source, then we (historians of religion) have misunderstood an essential aspect of how religion fit into the nexus of history or how we understand religion, so much so that what is being studied was capable of being fundamentally compromised without our observing it. 2) If the decline in religion was true, but came only from causes native to the category of religion, then the political events of the preceding decades (non-religion events) would have had very little impact on religion itself. In this context, there would be little reason to study religion and the American Revolution at all, though it would presumably still be necessary to track religious developments across those decades if only to avoid a chronological gap in our studies. (I think this is effectively what most historians of religion have been doing.) 3) If there was no decline in religion in an era of great anxiety about the subject (as evidenced by the Illuminati crisis), one should nonetheless be able to track the ways that religious categories and debates shifted in the new political environment. But implicitly, since the larger category itself was stable, one should also be able to track those shifting debates and categories in earlier eras, and also link them to the political narrative, given that scholars on both sides of the divide of the revolution do just that.

Historians looking at the Illuminati episode have largely followed one of the first two explanations above, assuming a decline to Morse’s public religion and locating the cause either in politics or in changes to religion itself. The problem is the very short time frame involved. Coming just before the election of 1800, the outcry has been presented as an example of Federalist resistance to Democratic political strategies and as a moment in transatlantic anti-Jacobinism. It has been used as evidence of the New England clergy’s eroding support for the French cause. Each of these represents important and fine-grained analysis of the politics of a tumultuous decade. The 1790s were marked by the stresses of the emerging political system of the United States, stresses that were rooted in the still new federal Constitution. The problems caused by relations with revolutionary France were also novel in the 1790s. That does not lessen the significance of these arguments, but historians’ focus on a quite short chronology here suggests that the rupture between the ancien régime (including pre-1789 and thus revolutionary America) and the 1790s was so great as to make longer-term explanations merely deep background.

The second frame for the Illuminati crisis emphasizes the kind of public religion Morse embraced and thus suggests explanations that stem from a broad cultural shift in the authority granted to that religion. Yet these explanations for the Illuminati moment remain similarly tight in chronological terms. Jonathan Sassi sees the episode as part of the Standing Order’s engagement with politics, a conscious fusing of religion and government that reflected the clergy’s effort to maintain its position. Amanda Porterfield has emphasized the incident’s partisan context in the process of highlighting the partisan content of religious anxiety in the era. Christopher Grasso integrates the episode into a longer span of history, but he too places the concerns of Morse and his colleague, Timothy Dwight, in the context of those divines’ desire to create a moral order for a newly rearranged society, emphasizing, again, the rupture of the 1790s. Taken together, Morse’s observers, like Morse, place critical importance on the radical rupture of the creation of the United States in the form of the federal Constitution as the definitive moment for his religion.

In both political and religious framings, historians have found a decline in Morse’s public form of religion, and their chronological framing implicitly endorses the first of our three explanations listed above, that of a political cause for the decline in religion. But what did the 1790s turn on? The elephantine Revolution in the room is obvious, and it hangs over the historical analysis in such a way as to justify a sense that a great deal was unstable in this difficult decade, certainly enough to explain away Morse’s hysterical anxiety. But the connections are perhaps less clear than they might be. Indulge me for a moment in a brief counterfactual: if the colonies had joined together in a new nation under the federal Constitution with the blessing of the British authorities in 1789, peacefully gaining independence and launching fully formed as a new nation, would we need to rethink any of the causes suggested above for explaining the Illuminati crisis? Without the long run up to the American Revolution, the controversies over an Anglican bishop and over the Quebec Act, without the bloody years of warfare, the clergy of the Standing Order in New England might still have been nervous about the intellectual developments of atheists like Paine, the French Revolution would still have been frightening and destabilizing, the new nation (born whole and without blood) would still be struggling to define a new political order including the religious terms of citizenship, and, to put a fine point on the matter, “religion” as Morse defined it would still be largely unchanged from what it had been under the colonial regime. At the time of the Illuminati crisis—though there were clear causes to worry about future trends that were rooted in very recent events—the institutions of Christianity and the institutional practice of theology (though not necessarily the beliefs of the theologians) were in many ways quite similar to what they had been in 1770 or 1760. These perspectives reflect Jon Bulter’s oft-quoted observation that the American Revolution was “a profoundly secular event,” as well as his persuasive argument that the eighteenth century saw a long increase of institutional Christianity.

In this counterfactual framing, our first explanation, religious decline caused by recent politics, is deeply unsatisfying. It suggests a too-rapid collapse of too powerful a system. Thus we glide to the second explanation: the system was decaying from the inside. Morse’s anxiety was the result of the rise of the secular. Here we have a different body of scholarship. Theoretically, at least, once “religion” developed as an intellectual category, it spawned its opposite, secularity. In the words of Charles Taylor, “the shift to secularity in this sense consists, among other things, of a move from a society where belief in God is unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace.” John Lardas Modern suggests that “secularism names a conceptual environment—emergent since at least the Protestant Reformation and early Enlightenment—that has made ‘religion’ a recognizable and vital thing in the world.” Indeed, Bryan Waterman recently made a related version of this argument with respect to the Illuminati crisis quite eloquently, linking it (and Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland) to contests for control of the public sphere.

It is important to note, however, that historians of the secular do not posit the decline of religion as a general category, but rather push us to identify the gradual metamorphosis that occurred as an older body of cultural beliefs and practices were first identified as religion and then began to divide into a series of different institutions and practices that we might today recognize in everything from civil religion to moral reform to the effort to spread human rights. In other words, historians of the secular advise us to be very wary of narratives of religious decline and call our attention to the power politics involved in the categorization of some cultural elements as religious and others as secular. Their version of history works much more comfortably with the many versions of dynamic religion from the early republic that do not match Morse’s. Here, therefore, is our third explanation: “religion” in the early republic was a dynamic category, encompassing a mixture of different things, populist revivalism, clerical voices, a new form of “secular” culture, and also traditional forms of Christianity. Because this is not a history of categorical religious decline and disappearance, but a proper history, a series of developments linked to moments of specific historical transition, it should be possible to chronicle it and show how it either registered the significant changes of the Revolutionary period or resisted them.

Unfortunately, historians of the secular have left us wondering about the role of the American Revolution in the story, and also the integration of this broader version of religion into the stream of time. Discussions of religion’s decline and the rise of the secular tend to focus on generalized versions of the cultural and political developments that occurred in the eighteenth century and all of the transformations that tend to be associated with the Age of Revolutions—the rise of a public sphere, the development of individualism, and a new embrace of popular sovereignty. They assume, even assert, the importance of historical contingency and change over time, but they avoid the dirty work such an assertion demands.

Without concrete links to the past, this version of scholarship slips dangerously close to becoming the doppelganger of our second explanation above, in which the course of history outside of religion is nearly irrelevant. The secular was born of elite non-religious (in Morse’s definition) intellectual trends before the political crises at the end of the eighteenth century, trends that were then made manifest in those broad-based political changes. (Note Modern’s vast and indistinct timing cited above.) Charles Taylor gives great causal weight to a broad phenomenon of deism, and he locates the development of his modern “social imaginary” in the eighteenth-century polite society. But, as Jon Butler has pointed out, Taylor’s “history is not for historians,” in other words, it lacks the specificity in detail and human action that historians require for effective argument. The upshot of these discussions for those concerned with secularity is that whatever changed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, afterwards people of faith moved in a world where unbelief and belief coexisted, as did religion, secularity, and various modes of public discourse that did or did not value the trained and authorized voice of the clergy. This changed “religion” from a part of the institutional fabric of public life (Morse’s “foundations” and “religion”) into a realm of thought, self definition, and anxiety in which people individually and collectively articulated their concerns about the new world order. These articulations are extremely useful for understanding the modern era, but unsatisfying for explaining its formation.

Nonetheless, these powerful intellectual narratives about religion and secularity have transformed how we understand religion and politics in the modern world. So much so that as historians we are certainly capable of recognizing the coexistence of Morse’s more narrow version of religion and the broader theoretical category which has secularity as its opposite. Yet our problem remains. For both the close chronological readings proposed by historians that find a meaningful transformation at the close of the American Revolution, and for the expansive readings of theorists, something significant happened during the American Revolution, or the Age of Revolution more generally. This matches an agreement in most other aspects of history, not to mention public discourse, that somehow the era was one of definitive change with lasting importance. We just have no real idea what it was when writing about religion.

Connecting the events of the Revolutionary chronology to religion, specifically to the religion that Morse identified, is not simple. Did the political changes of the Age of Revolution (or, more parochially, the American Revolution) matter to religion? If so, which changes and where? Did the stresses to Morse’s religion caused by the Age of Revolution and the long rise of secularism simply build in some sort of historical waiting area until they were able to burst onto the scene in the early republic? Did they matter to anyone along the way? Did listeners to public sermons in 1788, such as Ezra Stiles’s oft-cited “The United States Elevated to Glory and Honor,” know that they would shortly discard the tired ceremony of public religion for the appeals of secularism, perhaps including new and secular celebrations of what will now be termed civil religion? Were they looking forward to it? If the great wave of secularism and unbelief identified by historians of the secular was slowly growing and being furthered by the development of new modes of public speech, action, and organization during the decades of revolution, why did most of the clergy on both sides of the Atlantic side with their governments in the crisis?

This plodding insistence on timing and immediate causality may coexist uneasily with the great sweep of theory, but granting the broad historical significance of theoretical developments is not the same as explaining how and when that influence was felt. In eras of profound transition—revolutions—such matters become even more important, precisely because the divisions between historical periods often elide them. For historians of religion in the Age of Revolution, a great deal is at stake methodologically in this discussion, because it is ultimately the question of not just how but whether the political events of the era had any demonstrable impact on religion, whatever we mean by that term. If so, how, when, and where? If not, how do we account for such dramatic change in the period immediately following it?

Hence the persistent urge for the specific and the connection between the before and the after. This is, in essence, a plea for a full realization of the implications in the third logical proposition above. If religion and its nouveau riche cousin, secularity, have not declined in history but are concepts that can be used to track a moving conceptual frame, then this frame should have a history that can be integrated into that of the Age of Revolution. When was Morse’s “religion,” a limited but identifiable version of the concept, destabilized? The focus on public religion is demanded by the political events implicated. 1750 seems too early. Linda Colley, J.C.D. Clark, and many others have offered interpretations of the ancien régime Atlantic world that rely on religious prejudices—those between Protestants and Catholics and also those between various denominations of Protestants—to explain the American crisis. So when was the influence of the rising tide of secularism, of the strength of new, non-religious public spheres felt as a threat by religious communities? 1776? 1787? 1789? 1791? Or do we need a different timeline, one that draws from “religious” history? Was it 1770, when George Whitefield died? 1788, when the General Synod of the Presbyterian Church created a self-consciously national organization? 1798, when Jedidiah Morse and Timothy Dwight insisted that the Illuminati were undermining American society? If the issue is not framed by a narrow insistence on date, what of causality? Were the changes to the idea and place of religion in society in the early nineteenth century brought about by legal disestablishment (an uneven process by any count)? Were they caused by the rise of republican political ideology and its consequent impact on theology? (This argument suggests a sort of suicide for culturally influential religion, as the causal energy comes from within religious thought itself.) Were they caused by the political power of skepticism and atheism (a more diffuse causality, far harder to date and trace)?

In all of these intellectual constructions, the ties between the specific historical process of revolution (or revolutions) and the anxieties to be perceived in Morse’s writing are vague at best. For historians, the chronological rupture of the Revolution is too great. For theorists, the process is too broad to be attached to specific events. Both reflect the kind of generalized sense of change that Morse articulated, but neither integrate it into the era of change that preceded it. The enormity of the transformation posited by theorists of the secular demands historical investigation; the tendency of historians to separate the 1790s from the era before it sidesteps the kind of investigation that would be needed.

This discussion also raises the very intriguing possibility that the cultural and political upheavals of the American Revolution were only coincidental to the profound changes in the place of religion (by any definition) in public life in the new nation in the 1790s. Could the development of as important a concept as secularity be only coincidentally adjacent and attached only by remote evolutionary ties to the crises of the Age of Revolution? Here, by our long wandering path, is the question posed by the inescapable Jedidiah Morse’s histrionics. A positive answer to that question would invite a significant redefinition of the American Revolution as something minor enough to have had little impact on a remarkably resilient form of religion. Indeed, it would suggest that the political alignments our historical actors cared so much about were all merely noise. This is a proposition that is worthy of more investigation.

One final thought, more political than historical: I have noted that Jedidiah Morse is the darling of conservative Christian nationalists, those who protest too loudly of the orthodox (by which they mean evangelical) Christianity of the “Founding Fathers.” The inability of historians, or theorists, to grapple in the macro sense with the historical relationship between religion and the political process in the creation of the United States is, I suspect, one source of the difficulty academic historians have in offering a counter narrative to that of religious decline from the nation’s holy founding, a narrative that Morse both helped create and is regularly used to prove. The Christian nationalist narrative is profoundly bad history, and by letting Morse speak for us, and by failing to clarify the history he experienced in more concrete ways, we are left sputtering and ineffectual. A more solid understanding of what we mean by religion, and when and where it responded to a complex political era that preceded the pivotal 1790s, may be useful in that highly charged conversation.

Many thanks to Amanda Porterfield and Kathryn Lofton for their helpful feedback.

Jedidiah Morse, Doctor Morse’s Sermon on The National Fast, May 9th, 1798 (Boston, 1798).

Jedidiah Morse, A Sermon Exhibiting the Present Dangers, and Consequent Duties of the Citizens of the United States of America (New York, 1799).

Jonathan D. Sassi, A Republic of Righteousness: Public Christianity of the Post-Revolutionary New England Clergy (New York, 2001).

Christopher Grasso, A Speaking Aristocracy: Transforming Pubic Discourse in Eighteenth-Century Connecticut (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1999).

Christopher Grasso, “Skepticism and Faith: The Early Republic,” Commonplace 9:2 (2009).

Bryan Waterman, “The Bavarian Illuminati, the Early American Novel, and Histories of the Public Sphere,” William and Mary Quarterly 62 (January 2005): 9-30.

Seth Cotlar, “The Federalists’ Transatlantic Cultural Offensive of 1798 and the Moderation of American Democratic Discourse,” in Jeffrey L. Pasley, et al., eds., Beyond the Founders: New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2004), 274-299.

Richard J. Moss, The Life of Jedidiah Morse: A Station of Peculiar Exposure (Knoxville, Tenn., 1995).

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, Mass., 2007).

Michael Warner, et al. eds. Varieties of Secularism in a Secular Age (Cambridge, Mass., 2010).

John Lardas Modern, Secularism in Antebellum America (Chicago, 2011).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3 (Spring, 2015).

Kate Carté Engel teaches history at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of Religion and Profit: Moravians in Early America (2009). Her current book project, The Cause of True Religion: International Protestantism and the American Revolution, chronicles how that conflict transformed both the ideal and the reality of international Protestant community in the Atlantic world between 1763 and 1792.

Nothing dries up the air in a middle school classroom quite like the study of documents. In the well-respected, high-achieving suburban district on Long Island’s north shore where I teach, I am constantly seeking ways to engage and excite my seventh and eighth graders in their two-year survey of American History. Primary source materials are required reading for my students and have been the main focus of the new New York State social studies assessments, but my students often don’t know what to do with them. Most are content to let the experts handle the job of interpretation. As one seventh grader told me, “Smarter people have written about these things already; what is a thirteen-year-old going to find that is different?” Frustrated, I asked myself, “How can I prove her wrong?” Taking my cue from the students, I developed a step-by-step process to teaching how to read primary documents, one that emphasized acquiring interpretive skills by working first with visual images.

With my seventh graders, I begin by showing them eighteenth- and nineteenth-century editorial cartoons. Middle school students take everything literally and have a hard time understanding the sarcasm and often biting criticism of the cartoonist, but forcing them to reckon with it helps give them critical distance. During our study of the American Revolution I introduce the cartoon “The Horse America Throwing His Master” Without providing the title, I ask my students to look at the 1779 engraving and tell me what they see. The impulsive response is always, “A guy in a red suit getting thrown off a bucking bronco.”

Next, I write the cartoon’s title on the board and ask my seventh graders to look at the engraving once more, and tell me what they see now. Inevitably, some students connect the title and the meaning immediately while others learn it from their peers this time around. All realize, however, that the cartoon involves symbols with a “hidden meaning.” With this first step, my students move away from purely literal thinking.

To enhance their developing skill for interpreting the meaning behind primary documents, I then share with my class a selection of historical political cartoons and ask my students to identify the meaning of basic symbols frequently used in them, many of which are still used today: the donkey and the elephant, Uncle Sam, and the bald eagle. They’re usually thrilled to discover that these symbols actually mean something.

Next, I ask students to employ these and other symbols to make their own meanings: I ask them to draw their own editorial cartoons that comment on key historical events. Each year, during our study of the American Revolution, my students are asked to complete an interdisciplinary English/social studies project. Working as a team of four, students are assigned a major event of the war like the Battle of Yorktown. Within their groups, they compose both a factual news article and a political cartoon of the event. The news article is written from as many primary sources as they can gather. I also allow them to use secondary sources in the library because of the difficulty in finding firsthand sources for some of the topics I assign. The political cartoon is completed after the article because they must come up with some “point” of the event to editorialize. This is the hardest part. I use Ben Franklin’s “Join or Die” cartoon as my example, explaining how the pieces of the snake represent the different colonies that will not survive unless they join forces. Very often, I see students working on a simple illustration of the event rather than an editorial cartoon. This gives me the opportunity to sit with those students who still don’t understand and help them see what is the difference between the two.

When their projects are completed, the students present them orally, reading their news articles and explaining their cartoons in detail. Through group presentations, the students are exposed to many different symbols and ways of looking at the same event. Some of the more interesting cartoons I have received have included the members of the Continental Congress walking into the Second Continental Congress as their individual state flags with heads, and leaving as United States flags with heads. Another fine project was a drawing of the patriots depicted as eagles holding American flags, waving goodbye to the lobsters swimming back to England after the Battle of Yorktown. The student-artist began by drawing a picture of Washington defeating Cornwallis at Yorktown and pointing him back to England. We stretched it a bit and I asked him to think of some of the symbols we had discussed and to try to make the cartoon a bit more abstract. He exclaimed “Lobsters! I’ll make Cornwallis and his men lobsters!” He was so excited about the idea and then came up with the eagles all by himself. The final result was beautifully polished; it was a huge hit with the class. From this point on, he was always one of the first with his hand up to offer his interpretation when we examined political cartoons.

By this time, my students have acquired a whole toolbox of skills to help them interpret primary sources, especially visual materials. Next, I move to more complicated imagery. When we study the American Revolution, I distribute copies of Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre. I ask my seventh graders to mark ten things they see in the picture by circling, highlighting, or making marginal notes. When I solicit responses, they vary from the obvious “Butcher’s Hall” sign over the customs house to the more obscure “smirk on that guy’s face as he shoots the gun” and of course, “the bloody patriots.” They will sometimes see things I’ve never noticed. After making a list of the students’ responses on the board, I ask them to go a step further by answering some questions like, “What was the artist’s purpose in creating this engraving?” and “How did this depiction of the Boston Massacre turn many colonists against the British?” I usually break the class into groups of four so that they can discuss their ideas with one another. In addition, after reading excerpts from the depositions and testimony collected at the trial of the British soldiers, my students draw their own conclusions and write their own histories, complete with a thorough explanation of the engraving and their take on Paul Revere’s intentions in creating it.

In considering the Boston Massacre, then, I bring students to the textual sources through the visual ones. We begin with Revere’s engraving, and use this image to assess the written sources. Although I have not had to completely restructure my teaching to prepare my students for the state assessments they face, it is still a challenge every year to persuade middle schoolers to believe that learning through documents is a worthwhile and potentially enjoyable task. Of course, this is not to say that I have won over the masses and created a generation of primary document lovers. At the very least, I believe I have equipped them with the analytic tools to field the documents they encounter. My little “document detectives” may not always comprehend my enthusiasm for primary sources but the “light-bulb face” of understanding motivates me to carry on. And each year my classroom, papered with lobster cartoons, takes on a lovely red hue.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.1 (October, 2001).

Tracey Melandro has been teaching seventh- and eighth-grade social studies for the past nine years at East Northport Middle School in Long Island, New York. She is a contributing author to a new Teachers Network publication, How to Use the Internet in the Classroom (New York, 2001).

Some lessons from Iraq

What can the experiences of General Thomas Gage, commander of British forces in North America from 1763 to 1775, teach the United States Army in Iraq? The officers of a field artillery battalion posed that question to members of the Harvard history department in May 2006. Intrigued, I agreed to walk the Freedom Trail with these forty officers, to see the sites where those eighteenth-century events happened. I was the only civilian amidst all these soldiers, almost all of whom had already seen combat in Iraq, and their questions and observations challenged my views of the present war in Iraq, the American Revolution, and the responsibilities of a historian in a time of war.

The battalion major contacted the history department in March. He and his fellow officers had received word that they faced a year of urban fighting against an Iraqi “insurgency,” and they wanted to know if they could glean anything from the experience of British commanders in Boston before the Revolutionary War. In the e-mail exchange that followed, the major explained that the U.S. Army has a set of procedures and theories for Counter Insurgency Operations, or COIN; that these derived from close scrutiny of past insurgencies against established governments around the world; and that 1770s Boston appeared to fit the profile. The goal of COIN, he explained, is to discover the hard-core opposition within the population and deprive it of popular support through a combination of propaganda and material aid. In essence, these officers saw themselves as facing tactical and strategic challenges analogous to those of British General Thomas Gage, who had failed to arrest the rebel American leaders and restore order and loyalty in Boston.

I found this comparison surprising on a number of levels. Everything I had learned from studies of popular historical memory—books such as Alfred Young’s The Shoemaker and the Tea Party (1999) or David Hackett Fisher’s Paul Revere’s Ride (1994)—had taught me to expect public institutions and figures to adopt and claim the inheritance of national heroes and ignore parallels with historical enemies or villains. But these officers showed a striking comfort with comparing themselves to America’s former enemies. At the same time, their analogy between the war in Iraq and the American Revolution came close to equating Iraqi terrorists with the Founding Fathers. More broadly, I am often skeptical of attempts to draw analogies between past events and present ones. At worst, historians can cease to speak analytically and can become memory keepers, using the past for modern political reasons.

Historical memory operates differently in professional military circles, where soldiers look for insights that might help in life and death situations. Among these officers, the question of right and wrong at the siege of Boston had less significance than the question of how General Gage lost control of the situation. In other words, they did not speculate about morality and only wanted to learn what had worked and what hadn’t. That is not to say these men and women were totally utilitarian or Machiavellian. Counterinsurgency in today’s U.S. Army includes diffusing resistance by removing popular grievances against the army. Generally this means avoiding any open conflict and having as few casualties as possible. Many of these soldiers expressed pride that “doing it right” also meant saving lives. Others, however, expressed concerns that no army can avoid exacerbating tensions and thus feeding the political basis of an insurgency.

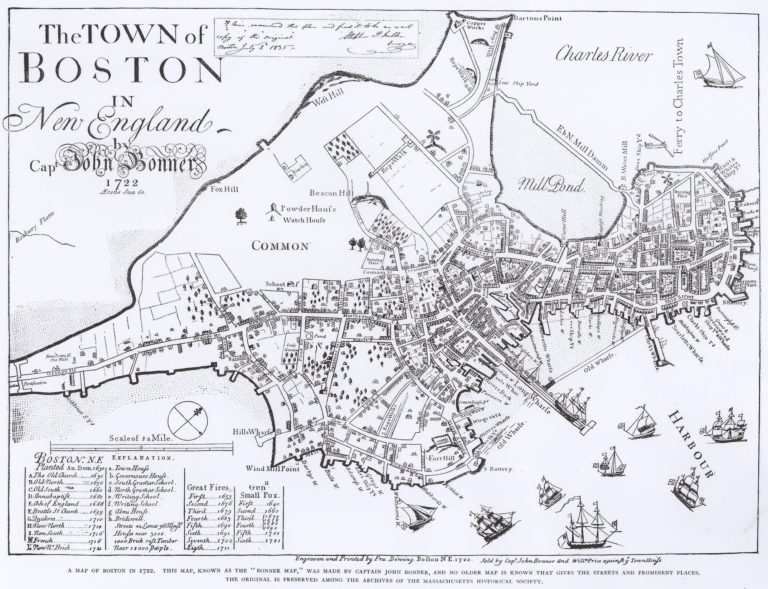

Our day on the Freedom Trail began at the Radisson Hotel next to the Boston Common, where the officers had spent the night and where I met them all for the first time. At first glance, they could have been any group of business people, but the large pile of camouflaged backpacks in the middle of the hotel lobby and their use of “sir” and “ma’am” gave them away as soldiers. I also noticed that the lieutenant colonel stood surrounded by his other soldiers, as if their training to protect the ranking officer remained effective even in Boston. After some short introductions, we walked across the common to our first Freedom Trail stop, the Old Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street in downtown Boston, where Samuel Adams, James Otis, Paul Revere, and the victims of the Boston Massacre are buried.

The Old Granary Burying Ground, with all its buried political worthies and massacre victims, seemed a good place to begin a discussion of American political culture on the eve of the American Revolution. My earlier brief review of army counter insurgency theory had revealed a fairly nuanced description of the relationship between political, religious, and military culture, not far removed from the work of “New Military Historians” of the past two generations, such as John Shy, Charles Royster, and Fred Anderson. Part of the American war effort in Iraq includes reshaping local government to be more democratic and cooperative with American counter insurgency measures. Battalion commanders have to oversee this process. The lieutenant colonel, the commanding officer of this battalion, asked whether political factionalism in the colonial period revealed a true democratic culture. He nodded immediately when I described four decades of recent scholarship on deference and gentry authority in Boston. Later, walking back to the hotel, he told me that his responsibilities in Iraq included overseeing the implementation of the new Iraqi Constitution but that he met with tremendous challenges when confronting local leaders and sheiks. That experience seemed to give him an intuitive understanding of the kind of patron-client power that lay behind the political authority of John Hancock, Andrew Oliver, or James Otis.

At each site, I quickly realized, the officers were looking for military lessons that spoke immediately to their specialty. I could tell from their level of attentiveness how closely they identified with the problems that the British faced in each of the events represented on the trail. Although I’m sure they were under orders to pay attention, it was clear to me that, as a group, they found some sites more relevant than others. Of the sites we saw, those connected with the Boston Tea Party and the Boston Massacre seemed to have the most value for them. At each of these sites, the officers presented me with almost piercing eye contact, and the major gave them some revealing takeaways from my narrative.

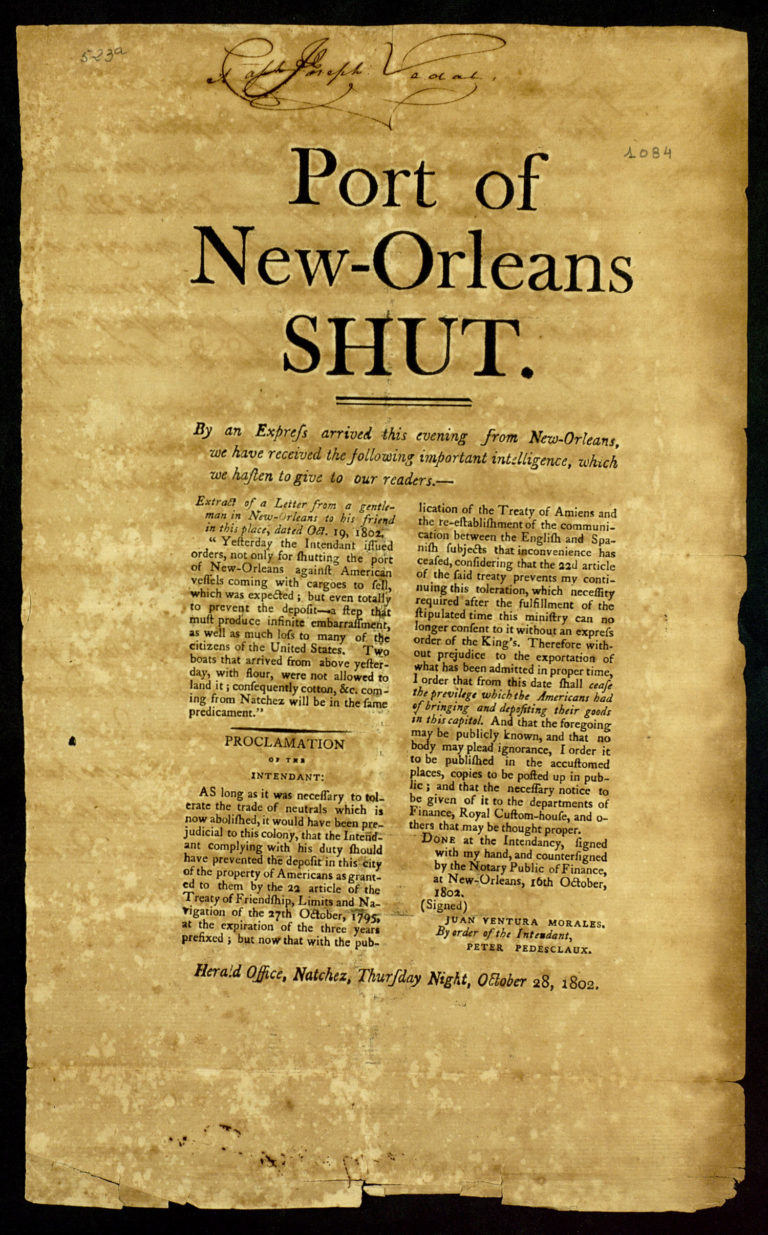

Built in 1729, the brick walls of the Old South Meetinghouse held the debate, on December 16, 1773, over the Parliamentary Tax on Tea, during which Samuel Adams signaled for the disguised “Mohawk” townsmen to attack the tea ships and dump three ships’ worth of the “poisonous Bohea” into Boston Harbor. On our trip to the site, the army had not budgeted for entrance fees, and the National Park had no special rate for soldiers, so we stood in the alley, and I described the meeting at the Old South, the dumping of the tea, and the British response with the coercive or “Intolerable Acts” that closed the port of Boston. For the major, the tea party presented a valuable lesson in the structure of insurgencies. He speculated that the Sons of Liberty had protected the anonymity of the members of their mob by forming what COIN terminology calls “cells,” small groups that only know their immediate commanders, not the whole structure of the resistance. I told them that no one knows exactly how it all worked but that the last survivor of the tea party, George Robert Twelves Hewes, certainly had some confused memories about that night, including a mistaken belief that John Hancock himself was aboard the ship. It is unclear, I told them, whether Hewes’s confusion might be evidence of a “cell” style organization of the Tea Party.

Since then, many of my colleagues have expressed frustration and even anger at the comparison between the Sons of Liberty and terrorist cells. Most historiography of early 1770s Boston argues that Gage was not facing an insurgency, which was understood in both Gage’s time and ours as a small but violent part of the population, but that he actually faced opposition from the majority of people in Boston. In a sense, describing the Sons of Liberty as an insurgency seems to understate the extent of popular outrage on the eve of the Revolution. The comparison, some have argued, raises the question of whether American commanders have repeated the mistake that Parliament made, of underestimating popular support for the resistance. At the Boston Massacre site, I had an opportunity to discuss with these officers the problem of popular support for resistance to the presence of an army and the question of when and how a military presence becomes counterproductive.

At the massacre site I was impressed with the sensitivity these officers had for the tenuousness of popular support for military forces. A six-foot diameter cobblestone circle between two busy streets marks the site of the Boston Massacre. The surrounding sidewalks are not large enough for forty soldiers, so they gathered around me in a circle across the street. I explained how the massacre seemed to be a series of accidents and escalations: a crowd had gathered to watch an apprentice pick on a private soldier, and then a captain had come to the soldiers’ aid with eight men and a corporal. I explained that Gage had standing orders not to fire on civilians under any circumstances but that someone heard the command to fire, the soldiers fired into the crowd, and five people died. The major stopped me there and turned to the other officers. In this kind of situation, he summarized, you must follow the rules of engagement. One small decision to fire against orders changed history and indefinitely alienated the majority of the population from the army.

It has been approximately fifteen months since I accompanied these officers on their Freedom Trail tour. Since then I have followed their experiences through Iraq on the regimental blog and on YouTube, where some of the officers have recorded home videos. I learned in February that one of the captains had been killed by a roadside bomb earlier that month. In April the chief warrant officer died in combat. At the end of May, the battalion lost a private and sergeant, both twenty-two, who ran into enemy small-arms fire while searching for a missing soldier from another unit. Members of the battalion have identified and eliminated several enemy weapons caches, opened several new markets, and helped train a brigade of Iraqis for combat service. Most of the blog entries describe their medical relief efforts in various regions. I like to think that our tour of the Freedom Trail reinforced the need to avoid conflict when possible and aid the local population.

At the end of my tour with these officers, we reached Copp’s Hill just as the early summer dusk began to paint the surrounding Boston skyline pink. This was where the British commanders watched the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. From the burial ground there, one can still look toward Dorchester Heights and Cambridge, where the Americans first formed a standing army to face the British. I gave a short history of the Revolutionary War and of the Continental Army in particular. When I explained that in 1780 Continental soldiers were forced to serve past their enlistment contracts because of troop shortages, one of the officers muttered volubly “some things never change.” Just this month as I write, these officers have had their second tour in Iraq extended by another three months. While I try to take every historical context and culture on its own separate terms, on some level I can’t help agreeing with that officer. Perhaps some things don’t change or at least they don’t change enough.

The most recent field manual for COIN operations is Department of the Army, Counterinsurgency, Field Manual 3-24 (Washington D.C., December 2006). For an example of the use of the word “insurgent” in the time of Gage, see Joseph Galloway, The Speech of Joseph Galloway, Esq.; one of the members for Philadelphia County: in answer to the speech of John Dickenson (Philadelphia, 1764), particularly pages 37-39. The most comprehensive published edition of Gage’s own papers is Clarence Edwin Carter, ed., The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage, 1763-1775, 2 vols. (Hamden, Conn., 1969).

This article originally appeared in issue 8.1 (October, 2007).

Philip Mead is a Ph.D. candidate in the history department at Harvard University. His dissertation examines interactions between civilians and soldiers in the Continental Army.

Baltimore | Boston | Charleston | Chicago | Havana

| Lima | Los Angeles | Mexico City | New Amsterdam | New Orleans

Paramaribo | Philadelphia | Potosi | Quebec City | Salt Lake City

Saint Louis | Santa Fe | San Francisco | Washington, D.C.

For more than a decade Bostonians have watched the progress of the Big Dig, described on the project’s official Website as a public works challenge on the scale of the Panama Canal, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, and the English Channel Tunnel (Chunnel). Thanks to an infusion of federal highway dollars, an unsightly elevated highway that has long separated the city’s North End from its commercial and civic core is about to be replaced with an eight-to-ten-lane underground highway. To create the massive tunnel, contractors removed sixteen million cubic yards of soil and underground debris.

Fewer people know about the little digs that preceded Boston’s Big Dig. Following federal guidelines, the Central Artery project allotted roughly four million dollars in the early 1990s for archaeological explorations in areas thought to be rich in early history and likely to be destroyed by construction. Ultimately four sites were chosen. One of the four, a patch of asphalt shaded by the old elevated highway, became known as the Cross Street back lot. Here archaeologists uncovered a seventeenth-century privy and in the privy an astonishing treasure–an artifact identified in Massachusetts’ new Commonwealth Museum as “North America’s Oldest Bowling Ball.”

Unlike the sleek balls used in modern candlepin bowling, seventeenth-century “lawn bowles” were flattened on two sides creating a profile more like a squished bun than a ball. The lathe-turned bowle found in the privy has a perforation on one side where a leaden weight was inserted to give it more play when rolled. When new, the hole would have been covered with a now-lost disc made from mother-of-pearl or ivory. Archaeologists found the bowle just below the collapsed floor of the privy in a layer of artifacts dating from the last decades of the seventeenth century. There is no way of knowing the exact date when the privy was built, though its size and construction generally conform to Boston regulations of 1652 requiring that any “house of office” (a euphemism for what contemporaries called a “shit house”) be no less than twelve feet from a neighboring house or street, be vaulted, and be at least six feet deep.

The careful construction of the privy shows town government at work in a period of urban expansion. Fifty years after the great Puritan migration of the 1630s, Boston had grown from a frontier settlement to a maritime and commercial center of forty-five hundred inhabitants. Although still a village by modern standards, it was the center of an expanding economy that linked the agriculture of its hinterland and the fishing and lumbering outposts of Maine and New Hampshire to a larger Atlantic economy. In the Cross Street privy, archaeologists found Caribbean shells, shards of Venetian glass, fragments of Iberian storage jars, broken bits of German, Dutch, and Italian tableware, and one oak lawn bowle.

Did the bowling ball accidentally fall in during the period when the “house of office” was in active use? Or was it part of the fill added about 1700 when the privy was altered? Either way, its presence suggests an underground Boston lurking beneath a presumably Puritan past.

Massachusetts’ earliest laws were hostile to bowling. A 1646 statute forbidding “the use of the Games of Shuffle-board and Bowling, in and about Houses of Common-entertainment,” was still in effect in the 1670s. (The same statute forbade dancing and the observance of Christmas and other English feast days.) Puritan lawmakers disliked bowling not only because it squandered “precious time” but because, in the language of the statute, it caused “much waste of Wine and Beer.” A certain amount of alcohol seemed essential to life, but when people began to hang around taverns playing at sports, they drank more than they needed. Bowling, then, went hand-in-ball with a series of what Englishmen and women would have known as urban vices: drunkenness, idleness, gambling.

By the early eighteenth century, however, the concept of recreation had replaced earlier anxieties about time wasting. In 1714, an enterprising Boston businessman advertised the opening of a bowling green “at the British Coffee House in Queen Street . . . where all gentlemen, merchants and others that have a mind to recreate themselves can be accomodated.” Boston’s bowle can be fitted, then, into a familiar story about secularization and the decline of Puritan piety.

But that interpretation is too simple. Puritan fathers would have had no need to pass laws against bowling unless some inhabitants of the town, even in the 1670s, found the pastime appealing. North America’s Oldest Bowling Ball doesn’t represent the transformation of a Puritan village into a provincial English town so much as it reveals contradictions present in Boston from its beginnings. In the 1630s as well as the 1670s, Boston was inhabited by libertines as well as orthodox Puritans, but in the last quarter of the seventeenth century, town leaders feared that they were losing control.