Winterthur XXX: Searching for early American erotica

A couple of years ago, I spent a semester-in-residence as a predoctoral fellow at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library, conducting dissertation research. My dissertation examines how representations of the female body helped to shape period constructions of femininity in late eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century America. With its rich and varied resources, Winterthur served as an ideal place to investigate my topic. Formerly the country estate of the DuPont industrialist family and located outside of Wilmington, Delaware, Winterthur today is a world-renowned institution devoted to the exhibition, study, and preservation of early American decorative arts. Its museum collections include over 85,000 objects made and used in America between 1640 and 1860. These holdings encompass an amazing breadth of media, forms, and styles, and range from the exceptional to the everyday. In one of over 175 period rooms fitted into the original family mansion and in latter-day galleries, the visitor can encounter neoclassical architectural elements, Chippendale furniture, Pennsylvania German Fraktur documents, Chinese export porcelain, Benjamin West paintings, Paul Revere silver tankards, and much, much more. Complementing this unsurpassed artifactual repository is Winterthur’s library, which has over a half a million books, periodicals, manuscripts, and other printed ephemera: primary and secondary sources pertaining to myriad aspects of American cultural life from the seventeenth through the early twentieth centuries.

Over the course of my residency at Winterthur, I found a treasure trove of materials related to my dissertation topic. There were almost daily discoveries of images of or information about the female body in the museum and library collections. Winterthur has an arsenal of searching tools to help the researcher cull through its vast holdings: computerized databases, published collections guides, and old-fashioned card catalogs, as well as knowledgeable staff. With these aides, I conducted a series of searches using subject terms, thematic categories, and iconographic classifications that seemed likely to identify items dealing with women’s bodies. For instance, I looked for art treatises (for aesthetic ideals about the nude figure); medical guides (for materials on obstetrics and gynecology); and allegorical works (for depictions of female personifications). Given the nature of my topic–female flesh and corporeality–another logical line of inquiry was for sexual and pornographic images. The search for early American erotica proved to be one of the more difficult ones, full of many trials and the occasional triumph (or titillation!). In this article, I recount my discovery of three pornographic objects lurking in Winterthur’s exhibits, bookshelves, and storage vaults. In addition to providing a glimpse “into the bedrooms” of the past, these artifacts also function as instructive case studies for some of the challenges facing the modern researcher. Such challenges are by no means unique to Winterthur; but rather, stem from wider historical phenomena, museum practices, and moral and aesthetic biases–all of which have affected the study of erotic materials.

But before I turn to my particular tale, a few remarks about nomenclature. In this article, the terms “erotica” and “pornography” denote artifacts that contain the explicit representation of sexual organs and activities, and that were intended to incite desire or transgress period standards of decorum. I use these terms interchangeably, although some scholars differentiate them on the basis that erotica has redeeming aesthetic merit, whereas pornography is purely for titillation. Such semantic distinctions seem inherently flawed since both beauty and desirability are in the eyes of the beholder; that is, they involve subjective value judgments. Erotic standards are also historically contingent: what would have raised eyebrows in the eighteenth century often seems laughably tame, even quaint to the modern viewer. In addition, I employ “pornography” anachronistically: the word did not enter the English language until the 1850s. Prior to this time, sexual imagery was described with a variety of terms, including “ribald,” “obscene,” “licentious,” “bawdy,” “lewd,” and “unchaste.”

![Fig. 1a. Fig. 1a. Hand-colored engraving from [Pierre-François-Hugues d'Hancarville], Veneres Uti Observantur in Gemmis Antiquis (s.n., 1771?), page 137, plate 27. Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection](http://commonplacenew.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/4.3.Sherry.1-300x259.jpg)

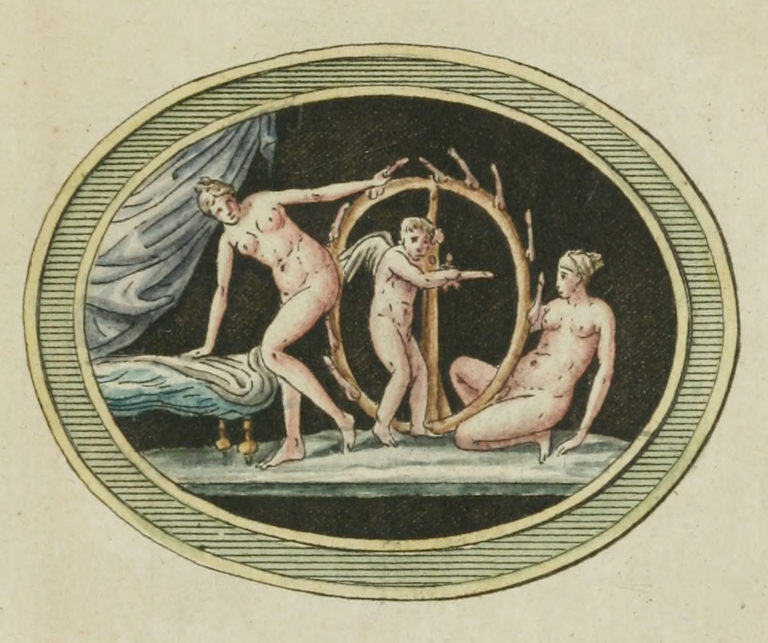

![Fig. 1b. Fig. 1b. Hand-colored engraving from [Pierre-François-Hugues d'Hancarville], Veneres Uti Observantur in Gemmis Antiquis (s.n., 1771?), page 96, plate 7. Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.](http://commonplacenew.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/4.3.Sherry.2-300x254.jpg)

My first and easiest discovery came from Winterthur’s library. It is a book entitled Veneres uti observantur in gemmis antiquis (Amours as observed in ancient gems) that I found cataloged under “erotic literature.” A luxury item produced in Europe in the 1770s, Veneres depicts classical carved gemstones in over sixty hand-colored plates, with brief captions in French. Many of the pictures contain graphic scenes of fertility rituals and sexual acts. In one plate, Venus, a satyr, and others make offerings to a statue of Priapus, the Roman god of generation who appears with his characteristically large and erect phallus (fig. 1a). Perhaps the kinkiest image shows two women playing with a wheel of dildos (fig. 1b)!

Veneres uti observantur in gemmis antiquis typifies much of the extant pornography from eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century America. In general, pictorial erotica was imported clandestinely from Europe. On both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, the audience for pornography was small and elite: gentlemen wealthy enough to afford such expensive items and erudite enough to have knowledge of Latin, French, and classical antiquities. (Not until the second quarter of the nineteenth century did erotica become mass-produced and widely available, with the help of new commercial printing and photographic technologies.) As is often the case with obscene materials from this earlier period, both the author and publisher of Veneres are not explicitly identified–an omission intended to protect them against social reproach. Nevertheless, the text is now attributed to Pierre-François-Hugues d’Hancarville (1719-1805), a French connoisseur who traveled around Europe cataloging the art collections of affluent patrons. It remains unknown, however, if the plates represent actual ancient artifacts. Scholars suspect that these illustrations are fabrications–pornography passed off with a wink and a nudge as an art historical study.

Veneres highlights some of the key difficulties facing the researcher of early American erotica: namely, the limited availability of such materials and the absence of historical documentation. What is arguably more surprising than the contents of d’Hancarville’s book is its continued existence given that very little pornography survives from colonial and early national America. This dearth of artifacts results from several causes above and beyond the vicissitudes of time. Prevailing notions of moral propriety led to the censure and censorship of materials with sexual themes. Just as d’Hancarville and his publisher tried to maintain anonymity, owners were reluctant to admit possession of such taboo items. Their descendents, too, have hidden and sometimes even destroyed potentially scandalous objects. Fortunately, Veneres survives, yet comes to us without a history, without a trace of the specific circumstances surrounding its creation, consumption, and reception. (Likewise, there is no documentation for the other pornographic objects in Winterthur’s collections.) Of course, any kind of historical research has its evidentiary gaps, but they are especially wide in the field of erotica. Such lacunae limit the scope of our understanding of these materials and the people who used them.

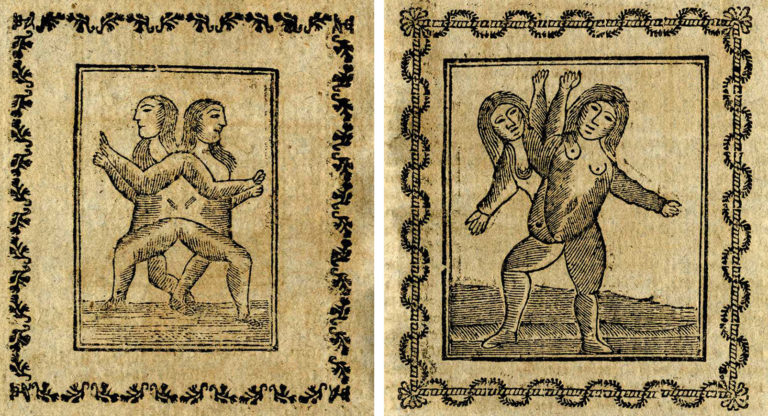

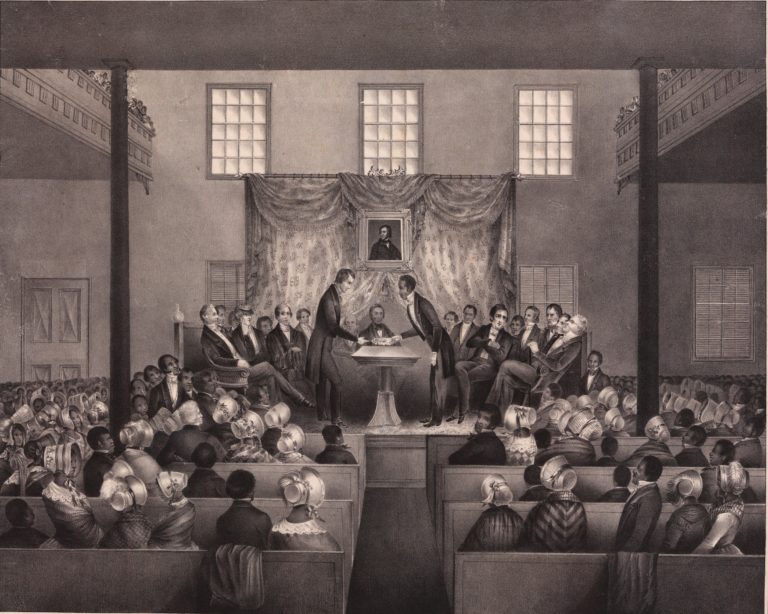

The next erotic object I discovered at Winterthur is a work of “homegrown” folk art: a kind of interactive peepshow now known by its modern title Gentlemen’s Amusement. Produced by an unknown craftsman in the first half of the nineteenth century, this extraordinary assemblage consists of a small rectangular cabinet containing the carved wooden figure of a Native American woman who holds the U.S. coat of arms. Two wooden soldiers in full military regalia flank the cabinet as if standing guard (fig. 2a). When Gentlemen’s Amusement is in the closed position, the woman’s face and the national crest are visible through windows in the cabinet door. When the door is opened and a hidden lever is shifted, the crest gets pulled aside exposing the fully naked body of the native female (fig. 2b). This pornographic toy was probably used by an all-male audience in a tavern, fraternal club, or some other place where men congregated.

For the modern researcher of American erotica, Gentlemen’s Amusement provides an interesting history lesson in the institutional treatment of pornographic collections. In several key ways, this peepshow structurally reproduces the “secret museum” or “private case” tradition in which curators kept obscene materials hidden, locked up, or otherwise restricted–just as Gentlemen’s Amusement places the naked woman in a cabinet under guard. This tradition began in the mid-eighteenth century, when the Museo Borbonico (today the National Museum of Naples) secretly stashed any pornographic artifacts excavated from Pompeii in locked vaults. In the following century, the British Museum in London and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, among other institutions, established their own versions of the private case. Such curatorial practices were intended to safeguard public morality, but gentlemen with enough clout and cash could still gain admission. Although Winterthur, opened in 1951, does not actually have a private case, the museum still in effect keeps certain indecent materials hidden from view. Gentlemen’s Amusement, for example, is displayed in the closed position and in a cluttered odds-and-ends room, off the beaten path of the more popular tour routes. (In order to see the full operation of the peepshow, one has to make a special appointment.) It is certainly understandable that Winterthur would want to avoid potentially offending a visitor, but such precautions pose a conundrum for the serious researcher: if one does not know about the existence of pornographic artifacts, how does one find them?

Sometimes, it is a matter of sheer luck, as in the case of my third “discovery”: a piece of mid-eighteenth-century Chinese export porcelain in the form of a tea saucer (fig. 3a). Produced in China for the Western market, porcelain items were imported in vast quantities by wealthy Americans throughout this period. Winterthur owns hundreds of such wares; but this one has an unusual feature. The top side of the saucer depicts a conventional and innocuous scene of a hunter and his dog set in a landscape. But on the bottom–a space usually left unembellished except for the maker’s mark–appears the image of a seated peasant woman who bares a breast and lifts up her skirts to reveal her underside (fig. 3b). A large leaf placed strategically over her genitalia mitigates the lewdness of her gestures. Like Gentlemen’s Amusement, this object plays with hidden pornographic contents and the owner’s privileged knowledge of their existence. Yet, in contrast to the peepshow, the saucer would have been used in polite, mixed company during the genteel social ritual of tea drinking. Part of its erotic charge would have come from the risk of exposing the ribald picture to the wrong–that is, an unappreciative–guest.

Despite my best efforts to be a thorough researcher, I did not find this saucer using any of the normal searching methods. In fact, I probably walked by it dozens of times in the museum where it hung with the top-side, hunter image facing out in a china cabinet, never suspecting it had a dirty underbelly. Nor did my virtual wanderings through Winterthur’s collections database lead me to identify the saucer as relevant to my project. Instead, I happened upon a reproduction of it in a book about porcelain while researching an unrelated topic. My failure to discover this object using the collections catalog underscores one of the chief problems in researching erotica: namely, the absence of a standardized classification system. In my database queries for pornographic imagery, I tried specific, sex-related terms including pornography, erotic, obscene, sex, and breast; as well as more generic descriptive words such as nude, naked, bare, and body. The results were inconsistent: none of these search terms yielded the saucer; “nude” flagged Gentlemen’s Amusement; and “pornography” got no hits.

Several interrelated, historical and museological factors have contributed to the lack of a uniform taxonomy for pictorial erotica. First of all, there is no consensus about precisely what makes a picture obscene. As former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously admitted in a 1964 opinion, he could not define pornography, adding, “[P]erhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it,” Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 198. Moreover, images often slip between pornography and art–as we saw with d’Hancarville’s Veneres uti observantur in gemmis antiques, which used classicizing iconography to cloak obscene pictures with an art historical respectability. From the perspective of museum curators, librarians, and other collections managers, there has not necessarily been a great demand to establish standardized typologies for erotica. As previously mentioned, there is a limited quantity of available artifacts due to low survival rates and persistent reticence about ownership. In addition, the sheer number of all kinds of things in Winterthur’s collections–coupled with its unparalleled strength in decorative arts–naturally focuses curatorial resources on works and themes deemed most significant to its educational mission. Relative to the rest of the holdings, erotica is marginal both in terms of quantity and importance; hence, it has not received special treatment in the cataloging process.

Speaking of cataloging, art museums do not have an industry-wide standard for classifying objects: there is no equivalent to the Library of Congress subject-headings index which most libraries (including Winterthur’s) use for books and other printed materials. According to curatorial conventions, decorative arts have been classified primarily by medium and form (e.g., porcelain and tea saucer), not by subject matter or iconography. Winterthur’s collections database does include a searchable field with a description of the item, but this field contains text in prose, rather than standardized terminology. In the case of the pornographic tea saucer, the underside image is described only as “a seated woman lifting her skirt, wearing rose and blue.” Another reason museums do not use taxonomic standards for erotica stems from the traditional art historical devaluation of such works. Scholars have tended to regard obscene images dismissively–as amusing, yet trivial curiosities from the past, not potential historical documents. Only in the past couple of decades as the history of human sexuality has developed into a field of academic study, have scholars started to analyze the material culture of sex, including pornography. Even with this recent interest, a comprehensive study of early American pictorial erotica remains to be written.

A final, minor challenge of researching pornography is of a personal rather than structural nature. I must confess that–out of concern of offending someone or of being branded a pervert–I always felt slightly embarrassed whenever I approached a Winterthur staff member for help in finding sexualized imagery. My fears were unfounded: the staff met my requests with equanimity and accommodation . . . and sometimes a little smirk! These experiences at the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library typify the kinds of difficulties that would be encountered at any institution with erotica in their collections. Yet despite the challenges–which include lingering moral prudery, limited availability of artifacts, anonymous production and use, institutional practices, and the absence of historical documentation and classificatory standards–the hunt for pornographic artifacts can be well worth the effort, not only for the “thrill” of the find, but also for the revealing glimpses they give us into the material lives and sexual culture of early Americans.

Further Reading:

Winterthur’s Website, which includes an online link to its library catalog (the museum’s collections database is not publicly accessible), is www.winterthur.org. On the cultural history of pornography in Europe and America, see: Lynn Hunt, ed., The Invention of Pornography: Obscenity and the Origins of Modernity, 1500-1800 (New York, 1993); Walter Kendrick, The Secret Museum: Pornography in Modern Culture, rev. ed. (Berkeley, Calif., 1996); and Peter Wagner, Eros Revived: Erotica of the Enlightenment in England and America (London, 1988). Examples of pictorial erotica from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century can be found in: Cottie Burland, Erotic Antiques or Love is an Antic Thing (London, 1974); and Milton Simpson, Folk Erotica: Celebrating Centuries of Erotic Americana (New York, 1994).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.3 (April, 2004).

Karen A. Sherry is currently completing her doctoral degree in art history at the University of Delaware and works as a curatorial intern at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.