Life Beyond Biography: Black Lives and Biographical Research

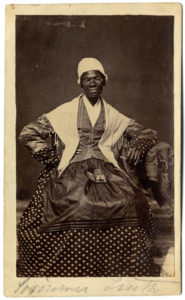

It is time to get over our fascination with biographies, and I say this as a scholar who specializes in a field, African American literature and history, in which one might wish for numerous biographies to emerge. For years, nineteenth-century African American history was, for many, just a small blank space. When asked to name as many nineteenth-century African American women as they can, my students generally struggle to come up with the predictable two that most people can manage: Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. They don’t fare much better, if even as well, when it comes to naming African American men. And even those in the field who can name a great number of people can’t usually tell you much about them. This is a field in which one comes to expect short biographical entries—when you can find one at all—that include the inevitable phrase “little is known.” Little is known about Kate Drumgoold beyond what she writes in her own autobiographical narrative. Until recently, little was known about Henry “Box” Brown after he successfully escaped from slavery and moved to England. Little is known about William Wells Brown’s approach to writing, since no original manuscripts exist. Little is known about nineteenth-century African American life and thought.

So why wouldn’t we want to know more—and what better way than by populating the literary landscape with biographies? Surely, this would be better than the biographical gestures we now encounter, brief sketches that are about as satisfying, and often about as accurate, as the many monuments and historical markers that James W. Loewen so painstakingly surveys in Lies Across America. And yet I think we should look beyond biographies if we want to do justice to the lives across America that have been so long assigned to obscurity.

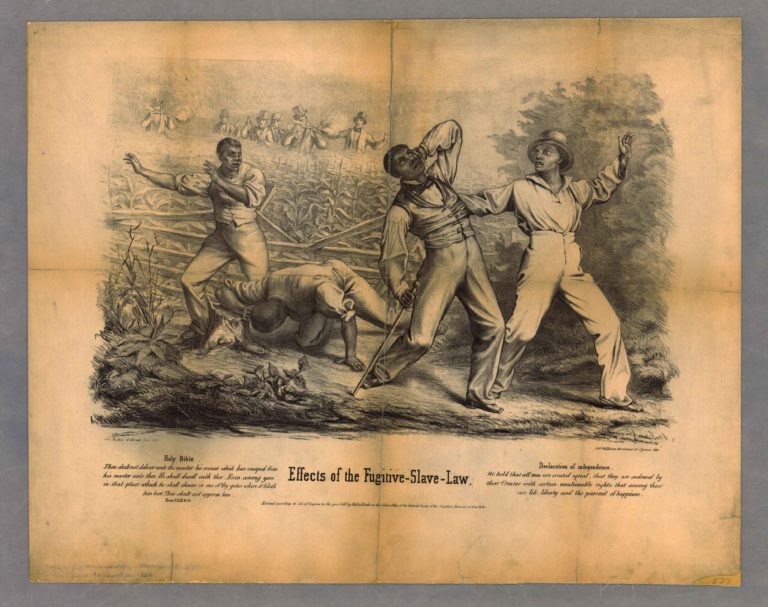

Let me begin by reviewing the nature of the problem. There are three main reasons why that helpless little phrase—“little is known”—is so annoyingly pervasive for those who research nineteenth-century African American history and literature. The first and most frustrating is that not much information has been found because no one has bothered to look. We’ve had, though, a few test cases that demonstrate how much can be found when someone actually takes the time to explore the archives. Harriet Wilson was virtually unknown, and then a rare find and a bit of an anomaly, and then an important entrance into black life in New Hampshire, and eventually a study in the complexly overlapping histories of abolitionism, spiritualism, African American women’s entrepreneurialism, and cultural mobility. Each new stage of research revealed much more about Wilson’s life and world, and other historical subjects as obscure as Wilson once was would no doubt benefit from the same sustained efforts. The second reason why “little is known” is because so much of the historical record has not been carefully preserved or formally archived. There are no manuscripts available for almost all of the writers I study—and in some cases, there are very few original documents that feature their writing at all, at least that we know of. The possibility exists that important documents are sitting in some unopened box in some unexplored corner of a library, or perhaps in a local historical society, or even in someone’s attic—depending on who recognized this history as worthy of preservation and what means they had for preserving it. In too many cases, though, we simply don’t have a rich or even clear trail to follow. The third reason “little is known” is because the overwhelming message of the most readily available, comprehensively preserved, and carefully archived historical record is that white lives are the ones that matter, and accordingly black lives are to be discovered, if at all, mainly in their connection with prominent white men and women. We have seen this important-by-association dynamic in histories of the antislavery movement, the Underground Railroad, and even in many histories of slavery that have been devoted, in whole or in part, to the lives of the enslaved. So those who go looking will often find themselves redirected, or will have to learn to read the cultural codes well enough to follow trails that lead only windingly, indirectly, to the subjects we are looking to study.

It would be natural enough, then, to want to know more, and especially to long for good biographies, but I hope we can do better than that—and if we want to capture the truths behind the slogan “Black Lives Matter,” we will need to do better than to aim for more biographies. I am not complaining about biographical research, mind you. Rather, I am questioning how that research is framed, how it is presented, who gets biographical attention, and what constitutes a just representation of an individual life.

To be fair, I should note that, my research interests and ethical commitments aside, I’m simply not a fan of narrative biographies. Certainly, I use them in my research, but I almost never read one from beginning to end, and when I do read them thoroughly, I usually do so in piecemeal fashion, starting someplace at the middle and reading out in both directions. I was a subject editor for the National African American Biography, a resource I use often, but even there, I see the narrative format simply as a convenient convention for conveying information. I simply don’t find a more-or-less-linear narrative focused primarily on an individual’s life to be useful in understanding the process and contours of that person’s life, the cultural and ideological networks that are part of that life, or the performative dynamics negotiated in that life—in short, the many relations, the winding paths, and the changing narrative lines that characterize anyone’s life. Life might be one damn thing after another, but an individual’s identity—involving the delicate play between the private and the public, the complex frameworks that shape how we will understand and relate to one another, and the extended networks in which we live and work—cannot be reduced to a linear narrative, however artfully crafted it might be.

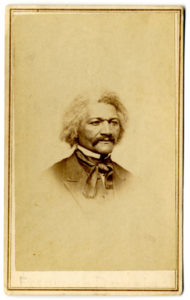

Think about the biographical challenges we face even in approaching some of the most famous and influential African Americans of the nineteenth century. Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Benjamin Banneker, and others were known largely through highly problematic narratives by white writers. When we turn to a figure like William Wells Brown, the biographical challenge is even more imposing. No one wrote about his life more frequently than Brown did in his various autobiographies, histories, and memoirs, but I’d challenge anyone to find a coherent self-presentation across those various autobiographical accounts—and a coherent biography drawn from his life misses the glimpse of Brown we get through his competing and contradictory autobiographical writings. Josiah Henson’s life was presented over a series of narratives, and in the later narratives, one can pretty much witness Henson disappearing into the legend that he was the model for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom. Getting at the reality of his life requires something more than finding the reality behind the fictional character who came to dominate his life. Frederick Douglass had the advantage of representing his own life over different autobiographies, but his autobiographies don’t tell an increasingly full and authoritative story so much as provide a case study in the challenge of a black American’s search for a narrative framework by which his life might be understood. Harriet Wilson might be said to have addressed the same challenge, which is why we are still debating whether to identify Our Nig as an autobiographical act or as a novel that draws from the slave narrative tradition.

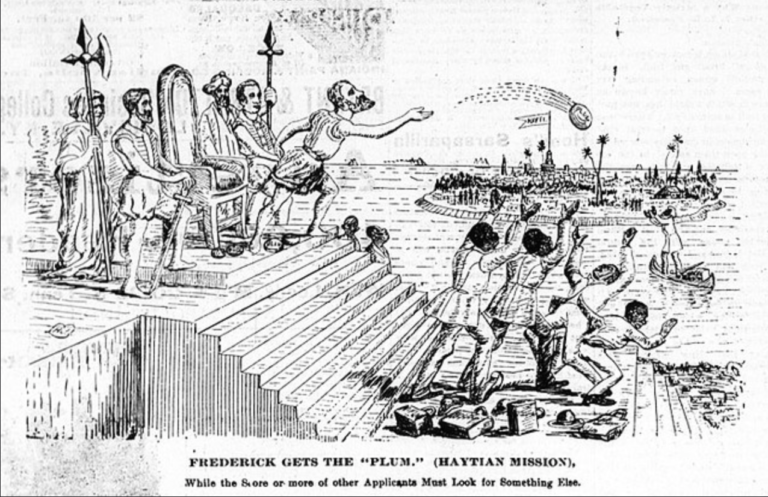

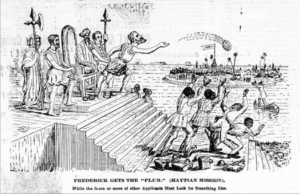

Rather than consider these various works as faulty biographical resources that can be corrected by a well-researched and authoritative biography, it might be better to ask why the African American writers who were most deeply invested in presenting their life story became instead examples of the limits of biography in understanding African American life. And as we answer that question, I believe we will discover why biography is problematic for approaching white lives as well. As Frederick Douglass realized when he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), it was dangerous to go public with your story. Douglass soon had to leave the country for England, to avoid the very real possibility that, having been outed and located by the published story of his life, he could be captured and returned to slavery. William Wells Brown was in a similar situation, but perhaps worried as well about what might happen to his story when it became public and others could lay claim to it. Whatever his motivation, Brown both revealed and concealed his story regularly in a life-long autobiographical performance that always kept the public on the other side of the mask. Barack Obama might understand Douglass and Brown better than anyone. Certainly, he knows the danger that people will use your story to try to return you to the past, and he understands as well that the world is ready to manipulate the details of your story and fit you to a caricature, so you need to handle your self-presentation carefully and creatively. One nod to a black preacher or a thoughtful response to racial injustice could set the media off beyond your control.

Little is known? One might well say that far too much is known to hold black lives within the comforting confines of a narrative biography. It is a simple fact—or perhaps a complex set of facts—that African American lives in the nineteenth century were governed by different laws of time, space, mobility, and affiliation than were those of white Americans. Even if we focus only on nominally free African Americans, we encounter a complicated set of legal and social conditions shaping virtually every moment of every day. Being denied public transportation, entrance into a hotel, or service at a restaurant is not simply an insult or an inconvenience; such obstructions pose serious logistical problems, complicate one’s relationship with whatever white American with whom one might be traveling, and introduce one to a different social group (whether white or black) willing to accommodate one’s needs. One’s responses to such challenges constitute significant moments in one’s self-definition, influencing how those around will view the nature of the problem in addition to how they will view one’s own character. And the people one encounters during such moments—the community of support one turns to, or the community of prejudice one encounters—might play an important role in one’s life. One learns to think differently about the time it will take to travel, about the arrangements one must make for food and shelter, about the degree of comfort and convenience one can expect, about the people one will encounter along the way, and about the ways in which one’s response to every situation will be read and judged.

My point, again, is not that we should abandon biographical research, and I am definitely not going to suggest that we should follow William Wells Brown and Harriet Wilson in mixing fiction and biography. I can definitely do without a world that encourages the proliferation of works like William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner, even if they were written by competent students of African American history, which Styron was not. Rather, I think there is value in looking at the kind of autobiographical tricksterism that we see in Brown, Wilson, and others, and I think we can learn from such examples of biographical violations as Styron’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. Styron shows the dangers not only of playing with the facts but also of biographies that fail to capture the complexities of the biographical subject’s world, the cultural contexts that any individual inhabits, the complex relation between background and foreground that we witness whenever we examine an individual life. At a time when we see inelegant Styronisms every time the news features what it takes to be the latest example either of black leadership or of black criminality, which for many amount to the same thing, it might pay to think about how we understand not only individual black lives but also the cultural frameworks by which black lives are positioned, obstructed, or realized. In doing so, we might come to appreciate why even today it is not unusual to encounter African Americans who find some measure of tricksterism a valuable approach in their self-presentation.

Even if we had biographies of the most prominent African Americans of the nineteenth century, we would be only moderately closer to understanding the realities of black life in their time. It’s striking, in fact, that biographies have been written thus far without the benefit of a robust recovery of so much of nineteenth-century African American history, and it’s striking as well that the biographies that have been pulled from the documentary remains of the past have not, with few exceptions, inspired a reinvigorated recovery effort of African American organizations, schools, presses, or social life. How is it possible to put together a book-length study of a black life without adding significantly to what we know of black lives generally?

Too often, African American biographies function as isolated, at times almost random, historical markers on an otherwise unmarked historical landscape. Instead of marking important sites of public memory, complex networks of only loosely associated or even contesting narratives of the past, and therefore forums for debate or for complex social and political negotiations, African American biographies tend to operate as isolated but all too familiar stories, tales of exceptional individuals. Biographies offer a kind of closure, a sense of resolution, of completeness. Arguably, a biography of Frederick Douglass should force one to realize how much about Douglass’s life and his world remains unknown, but it is all too possible for many readers to get through a biography of Douglass without even realizing that one has encountered very few African Americans along the way, that the biography’s index is populated primarily by white people, and that the documentary record favors the white American’s reading of history, even of black history, even of Douglass’s life.

I find myself thinking along these lines whenever I read a biography, thinking about how far removed it is from the lives I sense when reading autobiographies or local histories. We might encounter messy disputes with unresolved outcomes when we meditate on the role of genre in Wilson’s Our Nig, or on the accessibility of the autobiographical subject in the Narrative of Sojourner Truth, or on the use of sources in Brown’s My Southern Home, or on the development of a lifelong project of self-representation in Douglass’s autobiographies—but when we read the biography, everything comes together nicely. We might wonder at the extensive efforts to create the kinds of organizations that can stand in for a well-governed community that we encounter when we read about African Americans in Philadelphia, Boston, or New York in the early nineteenth-century, and we might leave the experience thinking about the hundreds of people involved, and the dozens of leaders we’ve discovered connected to the most prominent African Americans, but when we read a biography of Frederick Douglass, we see leadership presented on a more manageable scale. It’s not at all surprising that scholars of black literary and cultural history—Sylvia Wynter, Alexander G. Weheliye, Saidiya Hartman, Hortense Spillers, Lloyd Pratt, and others—increasingly are arguing for an understanding of what it means to be human that focuses on the collective, the performative, the unknown and unknowable. Nineteenth-century African Americans didn’t spend their days trying to prove to white Americans that they were in fact human. Instead, they forged new versions of humanism, taking communities formed by racist force and transforming them into communities devoted to ongoing and collective self-determination.

Ultimately, then, I want to suggest that we should question the assumed parameters of our research, the narrative construction, and even the focus of the biographies we either write or wish for. A useful example might be Jean Fagan Yellin’s biography of Harriet Jacobs, which was soon complemented by The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, including a searchable CD, that connects readers to the documentary world behind the biography—or the more old-school model, Philip S. Foner’s five-volume The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, which takes readers through a world of documents as well as a biographical narrative. A very recent and productive model of a useful approach is Robert Levine’s The Lives of Frederick Douglass, which begins by taking seriously the possibility that Douglass lived, in fact, many lives. Exploring Douglass’s various autobiographical writings, Levine presents a complexly fluid life, one fed by many streams. Obviously, this approach is limited to those individuals who were engaged in sustained and still-preserved acts of self-representation, but when available, this approach takes us much further than does the standard biography.

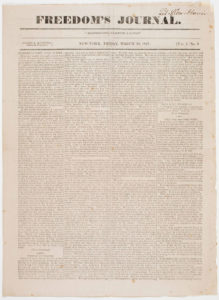

I value such approaches, but I’d like to find ways to reimagine biography altogether, first by looking back at early African American biographical texts. It is revealing, I suggest, that the promise of African American achievement has been represented so often by way of the distinct genre known as collective biographies—basically, collections of biographical sketches unconnected by any overarching narrative but all serving a central point about the importance of the people (usually, both famous and relatively unknown) represented by the volume as a whole. From William Wells Brown’s The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863) to such relatively recent works as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African American Achievement (1997), collective biographies have been a staple of African American publishing. African American history was always deeply enveloped, complexly contextualized by other histories, other communities, and often the overall story presented has been the product of an activist determination, both individual and collective, to resist the pressures of the defining contexts and surrounding communities.

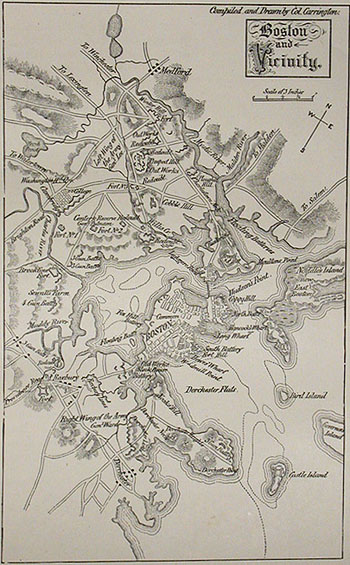

Today, that tradition is most strongly evident in the records painstakingly constructed by amateur historians and activists (both black and white) in the service of local or regional communities—for example, Mark J. Sammons and Valerie Cunningham’s Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage (2004), or H. H. Price and Gerald E. Talbot’s Maine’s Visible Black History: The First Chronicle of Its People (2006). Such local histories often lack an overarching or connecting narrative, beyond the overwhelming evidence of communities, lives, and events not accounted for elsewhere, and the guiding narrative of such histories almost always involves the painstaking attempt to gather together and preserve the fragmented records of isolated people and events so as to indicate a broader collective story not yet told and perhaps even unrecoverable as a single, coherent narrative. Like the Black Heritage Trails that are often associated with these texts, reading African American history can involve a more-or-less charted pilgrimage through a cultural landscape of important alliances across both space and time, sometimes a pilgrimage negotiated against the pressures and competing narratives of a nearly successful historical erasure. In these writings, the lives of apparently inconsequential people are placed next to biographies of the most prominent performers on the public stage, seemingly isolated incidents are placed next to grand historical battles, and what can be known is related to an imagined past and an envisioned future. This complex mix of historical focus, moreover, is usually framed by a social and political environment that is always provisional, shifting, and vulnerable—making it difficult to determine what might eventually emerge as central or marginal, as important or incidental.

Looking back at the collective biographies of the past makes it possible to look forward to what we might aim for today, when digital resources make a culturally rich approach to historical and biographical recovery more possible than it has ever been before. Rather than use the tools available to us to place newly imposing monuments on an otherwise scarcely populated historical landscape, we could use the lives we know best as entrance into the lives and the worlds that remain unknown to any but the most determined archival researchers among us. With the digital revolution, archives themselves are changing, and we accordingly have the opportunity to imagine a richer and more demanding history than ever before.

It is becoming increasingly possible to access the scattered documentary remains of the African American past wherever they are, and perhaps even to connect with the nontraditional archives—the bookstores, the churches, the fraternal organizations, the community organizations, the attics and basements—in which so much of what has been preserved of African American lives is held. This is a history that involves gathering together various historical sites and individual stories that replicate broad patterns of racial control and resistance, representing both an imposed and collectively determined communal identity, the feedback loops of U.S. racial history. This is also a history that involves attending to the local variations in that pattern, the unpredictable effects of the convergence of chaotic laws and incoherent social practices restricting or otherwise channeling community interactions and the possibilities of agency. In the feedback loops connecting history and memory, shaping both broad collective frameworks and specific communities, is a process—stable in its general contours, but unpredictable in its local manifestations, a combination of scripted identity and improvisational performance—central to any just understanding of African American history.

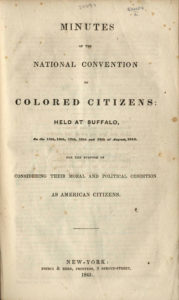

The biographies we most need now are those that actually represent complexly contextualized and interconnected lives—and we have the tools we need now for such biographical work. With the help of digital ego-networks, we can graph the system of relations connected with any biographical subject we wish to study. We can locate African American lives in black communities, and we can come to a better understanding of the relations among black and white Americans generally. Whether we enter by way of specific locales (Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, New Orleans), initiatives (the Colored Convention movement, the abolitionist movement, the women’s movement), or organizations (the A.M.E. Church, mutual benefit societies, the Prince Hall Freemasons), we can get a better sense of how black lives functioned, and how people worked together to ensure that their lives would matter. There are a couple of features of this approach that make it particularly attractive, and perhaps primary among them is that it would not be conceptualized primarily as an attempt to recover any one person’s biography, nor as an attempt to look at any single person’s life in isolation. At base, the purpose of such an approach would be not simply to recover and reprint but also to read and attend to the documents related to black lives in daily performance, and always with a piercing awareness of what we do not yet know, and at times even what we cannot hope to know.

In other words, such an approach would help us piece together the networks and patterns that emerge when we study people’s lives not as abstract and coherent individual stories, or independent tales, but as they were lived, in concert with others, often involved in various and even competing narratives, contributing to and benefitting from collective efforts. It is a matter of accounting for various historical and cultural attractors, various dynamics by which the turbulent forces that shape African American life acquired identifiable stability, the process by which cultural forces merged into cultural formations and by which black identity was claimed from within and not simply imposed from without.

In short, the approach that I’m looking for might lead us to focus more on recovering communities than on recovering individual narratives. This approach might help us get beyond the biographies that announce that one well-documented black life matters and enter more substantially into a recognition that Black Lives Matter, beyond the exceptional, representative, or putatively archetypal life stories, accounting for even those not fully represented in the documentary record. Not incidentally, such an approach might also help us highlight the networks of affiliation fundamental to whiteness—the networks of opportunities, standards of achievement, and environmental support for white Americans, which would in turn also highlight the importance of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Even for those who are not interested in studying African American history and literature, I think it would be good to get over the illusion that biographies provide a useful entrance into lives lived in the context of American history and culture. Even after many years engaged in African American Studies, having grown to expect the ongoing marginalization of my field, I’m still surprised to read a biography of a white American from the nineteenth century and discover that this story of a life richly lived has almost nothing to say about race or slavery. Certainly, it’s encouraging to encounter such books as Henry Wiencek’s An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America or David Waldstreicher’s Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution, but one can only reflect on how many biographies of these two “founding fathers” one can read without encountering slavery or race as not just a side note, and not even just as a prominent concern, but as a central, defining presence in these lives, and in the early life of the developing republic. And one can read any number of biographies of white American writers with almost no mention of race. They were white, after all, so why talk about race? What role could U.S. racial history possibly have when telling the story of a white person’s journey from obscurity to prominence—the early education, the eventual connections, the wonderful coincidences, the fortunate encounters, the ultimate self-discovery and determination to succeed, against all odds? What possible role would race play in such a story when the subject is white?

Autobiographies, biographies, and collective biographies have become such dominant genres in African American literary history because the challenge of relating the dynamics of black lives has always been and is still so daunting. As we look back and attempt to recover the many black lives that have emerged in research on African American history and print culture, even when we can gather reliable facts from the scattered documents available, we are faced with the task of accounting for the often absurd contexts, as shaped by white supremacist ideologies, within which those “facts” operated. Not incidentally, we are faced with the same task when approaching white lives, though that challenge remains largely invisible to the great majority of Americans, biographers included. But by finding more innovative and complex ways to approach black lives as actually lived, as collectively performed, as improvisationally imagined, we will find ourselves not only appreciating African American history but also reevaluating white American history—and thereby coming just a bit closer to a productive understanding of American history generally, one distinguished not by biographies along the road but by maps that show where the roads connect, and how they might be navigated. We all might then be able to follow those maps to discover where those who came before us lived, where we live now, and why it matters to get it right.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.1 (Fall, 2016).

John Ernest is the Judge Hugh M. Morris Professor of English and chair of the Department of English at the University of Delaware. He is the author or editor of twelve books, including Chaotic Justice: Rethinking African American Literary History (2009) and The Oxford Handbook of the African American Slave Narrative (2014).