There Arose Such a Clatter Who Really Wrote “The Night before Christmas”? (And Why Does It Matter?)

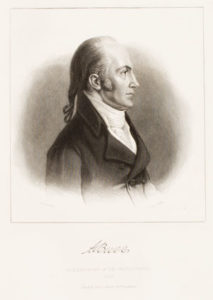

In a chapter of his just-published book, Author Unknown, Don Foster tries to prove an old claim that had never before been taken seriously: that Clement Clarke Moore did not write the poem commonly known as “The Night before Christmas” but that it was written instead by a man named Henry Livingston Jr. Livingston (1748-1828) never took credit for the poem himself, and there is, as Foster is quick to acknowledge, no actual historical evidence to back up this extraordinary claim. (Moore, on the other hand, did claim authorship of the poem, although not for two decades after its initial–and anonymous–publication in the Troy [N.Y.] Sentinel in 1823.) Meanwhile, the claim for Livingston’s authorship was first made in the late 1840s at the earliest (and possibly as late as the 1860s), by one of his daughters, who believed that her father had written the poem back in 1808.

Why revisit it now? In the summer of 1999, Foster reports, one of Livingston’s descendants pressed him to take up the case (the family has long been prominent in New York’s history). Foster had made a splash in recent years as a “literary detective” who could find in a piece of writing certain unique and telltale clues to its authorship, clues nearly as distinctive as a fingerprint or a sample of DNA. (He has even been called on to bring his skills to courts of law.) Foster also happens to live in Poughkeepsie, New York, where Henry Livingston himself had resided. Several members of the Livingston family eagerly provided the local detective with a plethora of unpublished and published material written by Livingston, including a number of poems written in the same meter as “The Night before Christmas” (known as anapestic tetrameter: two short syllables followed by an accented one, repeated four times per line–“da-da-DUM, da-da-DUM, da-da-DUM, da-da-DUM,” in Foster’s plain rendering). These anapestic poems struck Foster as quite similar to “The Night before Christmas” in both language and spirit, and, upon further investigation, he was also struck by telling bits of word usage and spelling in that poem, all of which pointed to Henry Livingston. On the other hand, Foster found no evidence of such word usage, language, or spirit in anything written by Clement Clarke Moore–except, of course, for “The Night before Christmas” itself. Foster therefore concluded that Livingston and not Moore was the real author. The literary gumshoe had tackled and solved another hard case.

Foster’s textual evidence is ingenious, and his essay is as entertaining as a lively lawyer’s argument to the jury. If he had limited himself to offering textual evidence about similarities between “The Night before Christmas” and poems known to have been written by Livingston, he might have made a provocative case for reconsidering the authorship of America’s most beloved poem–a poem that helped create the modern American Christmas. But Foster does not stop there; he goes on to argue that textual analysis, in tandem with biographical data, proves that Clement Clarke Moore could not have written “The Night before Christmas.” In the words of an article on Foster’s theory that appeared in the New York Times, “He marshals a battery of circumstantial evidence to conclude that the poem’s spirit and style are starkly at odds with the body of Moore’s other writings.” With that evidence and that conclusion I take strenuous exception.

By itself, of course, textual analysis doesn’t prove anything. And that’s especially true in the case of Clement Moore, inasmuch as Don Foster himself insists that Moore had no consistent poetic style but was a sort of literary sponge whose language in any given poem was a function of whichever author he had recently been reading. Moore “lifts his descriptive language from other poets,” Foster writes: “The Professor’s verse is highly derivative–so much so that his reading can be tracked . . . by the dozens of phrases borrowed and recycled by his sticky-fingered Muse.” Foster also suggests that Moore may even have read Livingston’s work–one of Moore’s poems “appears to have been modeled on the anapestic animal fables of Henry Livingston.” Taken together, these points should underline the particular inadequacy of textual evidence in the case of “The Night before Christmas.”

Nevertheless, Foster insists that for all Moore’s stylistic incoherence, one ongoing obsession can be detected in his verse (and in his temperament), and that is–noise. Foster makes much of Moore’s supposed obsession with noise, partly to show that Moore was a dour “curmudgeon,” a “sourpuss,” a “grouchy pedant” who was not especially fond of young children and who could not have written such a high-spirited poem as “The Night before Christmas.” Thus Foster tells us that Moore characteristically complained, in a particularly ill-tempered poem about his family’s visit to the spa town of Saratoga Springs, about noise of all kinds, from the steamboat’s hissing roar to the “Babylonish noise about my ears” made by his own children, a hullabaloo which “[c]onfounds my brain and nearly splits my head.”

Assume for the moment that Foster is correct, that Moore was indeed obsessed with noise. It is worth remembering in that case that this very motif also plays an important role in “The Night before Christmas.” The narrator of that poem, too, is startled by a loud noise out on his lawn: “[T]here arose such a clatter / I got up from my bed to see what was the matter.” The “matter” turns out to be an uninvited visitor–a household intruder whose appearance in the narrator’s private quarters not unreasonably proves unsettling, and the intruder must provide a lengthy set of silent visual cues before the narrator is reassured that he has “nothing to dread.”

“Dread” happens to be another term that Foster associates with Moore, again to convey the man’s dour temperament. “Clement Moore is big on dread,” Foster writes, “it’s his specialty: ‘holy dread,’ ‘secret dread,’ ‘need to dread,’ ‘dreaded shoal,’ ‘dread pestilence,’ ‘unwonted dread,’ ‘pleasures dread,’ ‘dread to look,’ ‘dreaded weight,’ ‘dreadful thought,’ ‘deeper dread,’ ‘dreadful harbingers of death,’ ‘dread futurity.'” Again, I’m not convinced that the frequent use of a word has terribly much significance–but Foster is convinced, and in his own terms the appearance of this word in “The Night before Christmas” (and at a key moment in its narrative) ought to constitute textual evidence of Moore’s authorship.

Then there’s the curmudgeon question. Foster presents Moore as a man temperamentally incapable of writing “The Night Before Christmas.” According to Foster, Moore was a gloomy pedant, a narrow-minded prude who was offended by every pleasure from tobacco to light verse, and a fundamentalist Bible thumper to boot, a “Professor of Biblical Learning.” (When Foster, who is himself an academic, wishes to be utterly dismissive of Moore, he refers to him with a definitive modern putdown–as “the Professor.”)

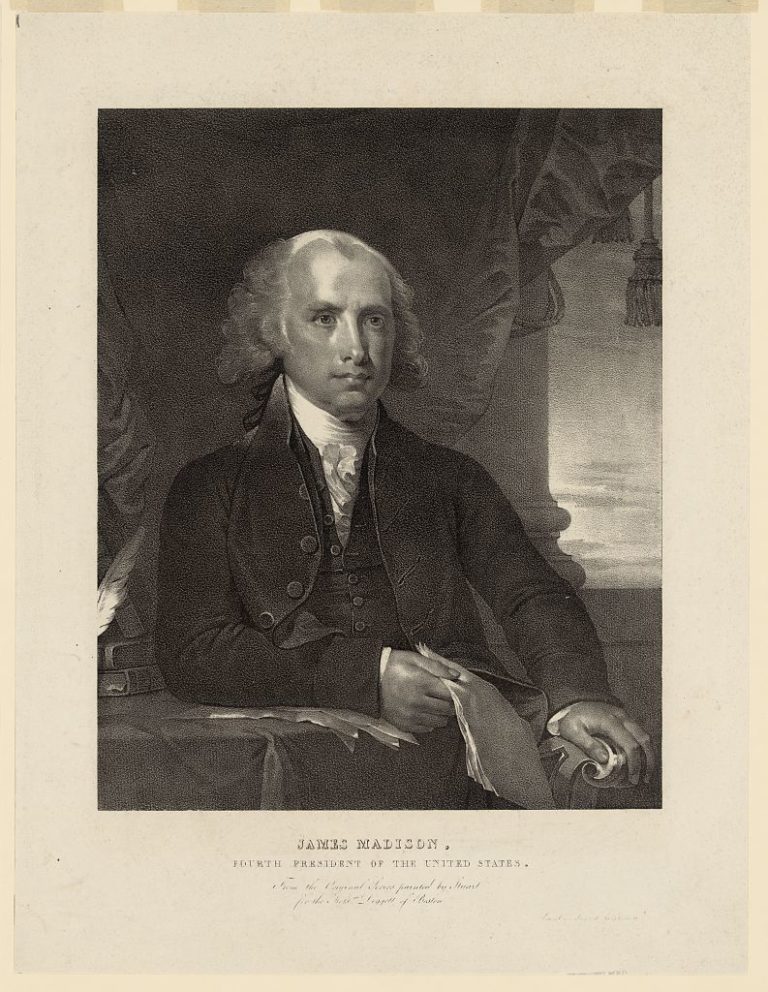

But Clement Moore, born in 1779, was not the Victorian caricature that Foster draws for us; he was a late-eighteenth-century patrician, a landed gentleman so wealthy that he never needed to take a job (his part-time professorship–of Oriental and Greek literature, by the way, not “Biblical Learning”–provided him mainly with the opportunity to pursue his scholarly inclinations). Moore was socially and politically conservative, to be sure, but his conservatism was high Federalist, not low fundamentalist. He had the misfortune to come into adulthood at the turn of the nineteenth century, a time when old-style patricians were feeling profoundly out of place in Jeffersonian America. Moore’s early prose publications are all attacks on the vulgarities of the new bourgeois culture that was taking control of the nation’s political, economic, and social life, and which he (in tandem with others of his sort) liked to discredit with the term “plebeian.” It is this attitude that accounts for much of what Foster regards as mere curmudgeonliness.

Consider “A Trip to Saratoga,” the forty-nine page account of Moore’s visit to that fashionable resort which Foster cites at length as evidence of its author’s sour temperament. The poem is in fact a satire, and written in a well-established satirical tradition of accounts of disappointing visits to that very place, America’s premier resort destination in the first half of the nineteenth century. These accounts were written by men who belonged to Moore’s own social class (or who aspired to do so), and they were all attempts to show that the majority of visitors to Saratoga were not authentic ladies and gentlemen but mere social climbers, bourgeois pretenders who merited only disdain. Foster calls Moore’s poem “serious,” but it was meant to be witty, and Moore’s intended readers (all of them members of his own class) would have understood that a poem about Saratoga could not be any more “serious” than a poem about Christmas. Surely not in Moore’s description of the beginning of the trip, on the steamboat that was taking him and his children up the Hudson River:

Dense with a living mass the vessel teem’d;

In search of pleasure, some, and some, of health;

Maids who of love and matrimony dream’d,

And speculators keen, in haste for wealth.

Or their entrance into the resort hotel:

Soon as arriv’d, like vultures on their prey,

The keen attendants on the baggage fell;

And trunks and bags were quickly caught away,

And in the destin’d dwelling thrown pell-mell.

Or the would-be sophisticates who tried to impress each other with their fashionable conversation:

And, now and then, might fall upon the ear

The voice of some conceited vulgar cit,

Who, while he would the well-bred man appear,

Mistakes low pleasantry for genuine wit.

Some of these barbs retain their punch even today (and the poem as a whole was plainly a parody of Lord Byron’s hugely popular travel romance, “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”). In any case, it is a mistake to confuse social satire with joyless prudery. Foster quotes Moore, writing in 1806 to condemn people who wrote or read light verse, but in the preface to his 1844 volume of poems, Moore denied that there was anything wrong with “harmless mirth and merriment,” and he insisted that “in spite of all the cares and sorrows of this life, . . . we are so constituted that a good honest hearty laugh . . . is healthful both to body and mind.”

Healthy too, he believed, was alcohol. One of Moore’s many satirical poems, “The Wine Drinker,” was a devastating critique of the temperance movement of the 1830s–another bourgeois reform that men of his class almost universally distrusted. (If Foster’s picture of the man is to be believed, Moore could not have written this poem, either.) It begins:

I’ll drink my glass of generous wine;

And what concern is it of thine,

Thou self-erected censor pale,

Forever watching to assail

Each honest, open-hearted fellow

Who takes his liquor ripe and mellow,

And feels delight, in moderate measure,

With chosen friends to share his pleasure?

This poem goes on to embrace the adage that “[t]here’s truth in wine” and to praise the capacity of alcohol to “impart / new warmth and feeling to the heart.” It culminates in a hearty invitation to the drink:

Come then, your glasses fill, my boys.

Few and constant are the joys

That come to cheer this world below;

But nowhere do they brighter flow

Than where kind friends convivial meet,

‘Mid harmless glee and converse sweet.

These lines would have done pleasure-loving Henry Livingston proud–and so too would many others to be found in Moore’s collected poems. “Old Dobbin” was a gently humorous poem about his horse. “Lines for Valentine’s Day” found Moore in a “sportive mood” that prompted him “to send / A mimic valentine, / To teaze awhile, my little friend / That merry heart of thine.” And “Canzonet” was Moore’s translation of a sprightly Italian poem written by his friend Lorenzo Da Ponte–the same man who had written the libretti to Mozart’s three great Italian comic operas, “The Marriage of Figaro,” “Don Giovanni,” and “Cosi Fan Tutte,” and who had immigrated to New York in 1805, where Moore later befriended him and helped win him a professorship at Columbia. The final stanza of this little poem could have referred to the finale of one of Da Ponte’s own operas: “Now, from your seats, all spring alert, / ‘Twere folly to delay, / In well-assorted pairs unite, / And nimbly trip away.”

Moore was neither the dull pedant nor the joy-hating prude that Don Foster makes him out to be. Of Henry Livingston himself I know only what Foster has written, but from that alone it is clear enough that he and Moore, whatever their political and even temperamental differences, were both members of the same patrician social class, and that the two men shared a fundamental cultural sensibility that comes through in the verses they produced. If anything, Livingston, born in 1746, was more a comfortable gentleman of the high eighteenth century, whereas Moore, born thirty-three years later in the midst of the American Revolution, and to loyalist parents at that, was marked from the beginning with a problem in coming to terms with the facts of life in republican America.

Don Foster also claims that Clement Clarke Moore loathed children, but from the 1820s on–after he was forty, and beginning at the very time “The Night before Christmas” was first published–Moore seems (like many other Americans) to have found satisfaction and something like serenity by taking emotional refuge in the ordinary pleasures of family life. His later poems show him as a doting father, a man who cherished domesticity and loved to spend what we would now call “quality time” with his six children. (His wife died in 1830, and it is clear that he cared to provide serious moral training along with lots of indulgence.) “Lines Written after a Snow-Storm” could almost be titled “The Morning after Christmas”:

Come children dear, and look around;

Behold how soft and light

The silent snow has clad the ground

In robes of purest white . . .

You wonder how the snows were made

That dance upon the air,

As if from purer worlds they stray’d,

So lightly and so fair.

(It is true that the poem concludes allegorically, by pointing out that the snow will soon melt. But that does not make it any less child-centered and affectionate.) In another later poem, Moore recalled his own childhood and his parents putting him to sleep:

Whene’er night’s shadows call’d to rest,

I sought my father, to request

His benediction mild:

A mother’s love more loud would speak,

With kiss on kiss she’d print my cheek,

And bless her darling child.

Moore actually based one of his poems on a homework assignment one of his own children had received at school. That poem, “The Pig and the Rooster,” was in anapestic tetrameter, the poetic meter of “The Night before Christmas.” (Don Foster makes the curiously self-defeating claim that “The Pig and the Rooster” was “modeled on the anapestic animal fables of Henry Livingston.”) But what is just as significant is that Moore took such an interest in his son’s homework that he would write a poem about it.

Even in “The Wine Drinker,” Moore reserves what may be his deepest scorn for the fact that the temperance movement was willing to exploit innocent children for political ends. There is no ironic humor but only what Moore called “indignant feelings” in these lines (which bring to mind the tactics of modern anti-abortion organizers):

Children I see paraded round,

In badges deck’d, with ribbons bound,

And banners floating o’er their head,

Like victims to the slaughter led . . .

How can ye dare to fill a child,

Whose spirits should be free and wild,

And only love to run and romp,

With vanity and pride and pomp?

But it may be his long poem “A Trip to Saratoga” that shows Moore at his most child-centered. While this poem is social satire, even more fundamentally it is the story of a widowed father who, in the face of all his own feelings, allows his six children to persuade him to leave his beloved fireside–“the pure delights of their dear home”–and take them for the summer to a place he well knows will prove a vulgar disappointment. Foster says this poem shows Moore’s loathing of children, and especially of their “noise.” It is true that Moore begins the poem with his six children simultaneously begging their father, over breakfast, to take them on “a summer trip,” and that he responds by asking for a little order (Foster quotes only the last two of these lines):

“One at a time, for pity’s sake, my dears,”

Half laughing, half provok’d, at length he said,

“This babylonish din about my ears

Confounds my brain, and nearly splits my head.”

The Clement Moore whom Foster gives us would have simply ordered his children to shut up–but this father soon gives in to his children’s demands. And from this point on, for the remainder of the poem, he displays nothing but affection for them. When, as he reports, they get bored on the train out of New York City and “begin to pant for somewhat [i.e., something] new”–this is on the very first day of the trip–Moore reports what any modern parent will find easy to recognize, as the children begin

To ask the distance they still had to go;

At what abode they were to pass the night;

Their progress seems continually more slow;

They wish’d that Albany would come in sight.

Hardly the tone of a man who was incapable of tolerating children. And, let us not forget, this was a single parent dealing by himself with six of them.

In fact, Moore is pleased pink with his kids, with their behavior, their personalities, and even their physical beauty. Saratoga may have been filled with beautiful belles, Moore acknowledges–but his own eldest daughter was “the loveliest of them all.” Even when this same daughter argues with her father, and he rebuts her argument with a single dismissive word–this is at the very beginning of the poem–Moore lets us in on his real feelings when he tells us that his “brisk retort [was] made”

With half a smile, and twinkle of the eye

That spoke–“You are a darling saucy jade.”

In just the same voiceless fashion, in a far better-known poem generally attributed to the same author, it is with a smile–and, yes, with eyes that twinkle–that Santa Claus lets us know that he means well.

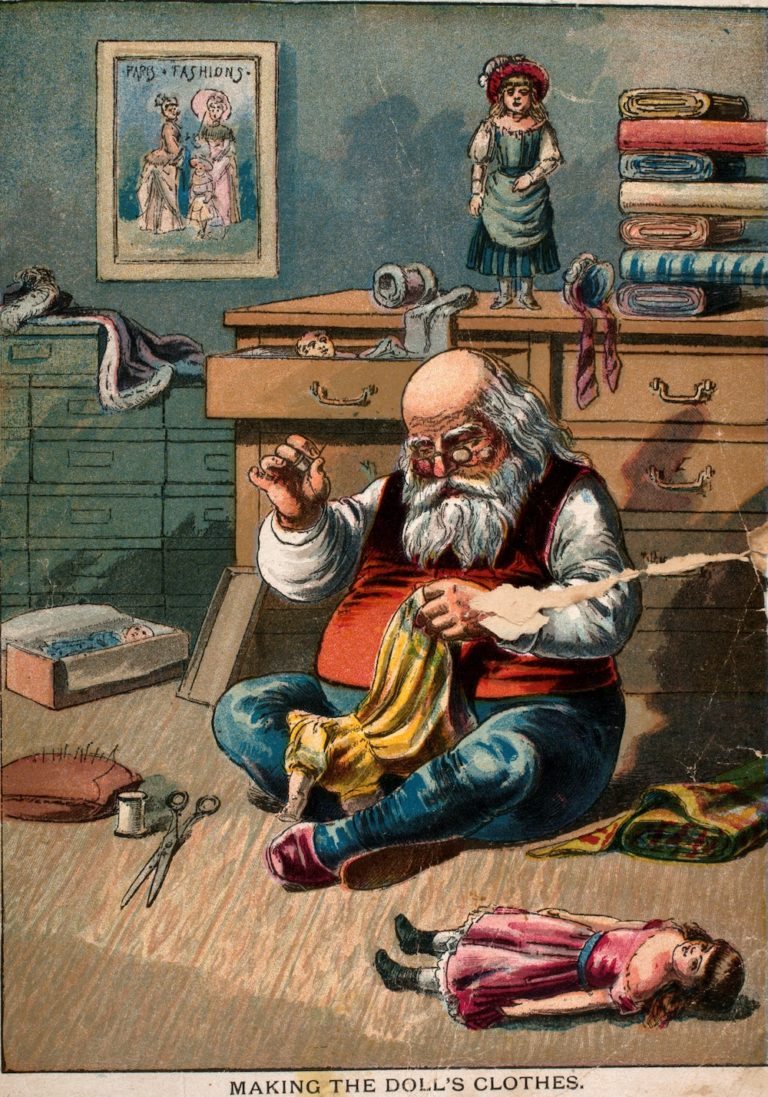

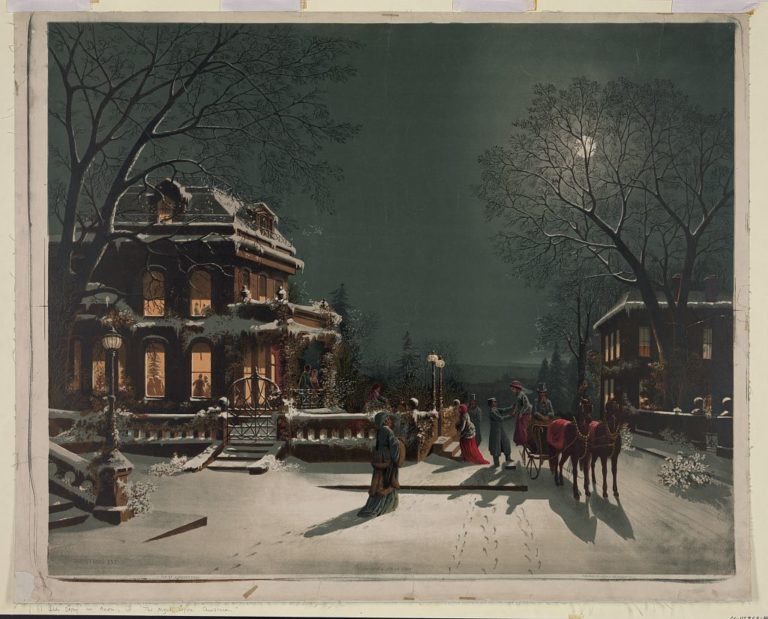

![]()

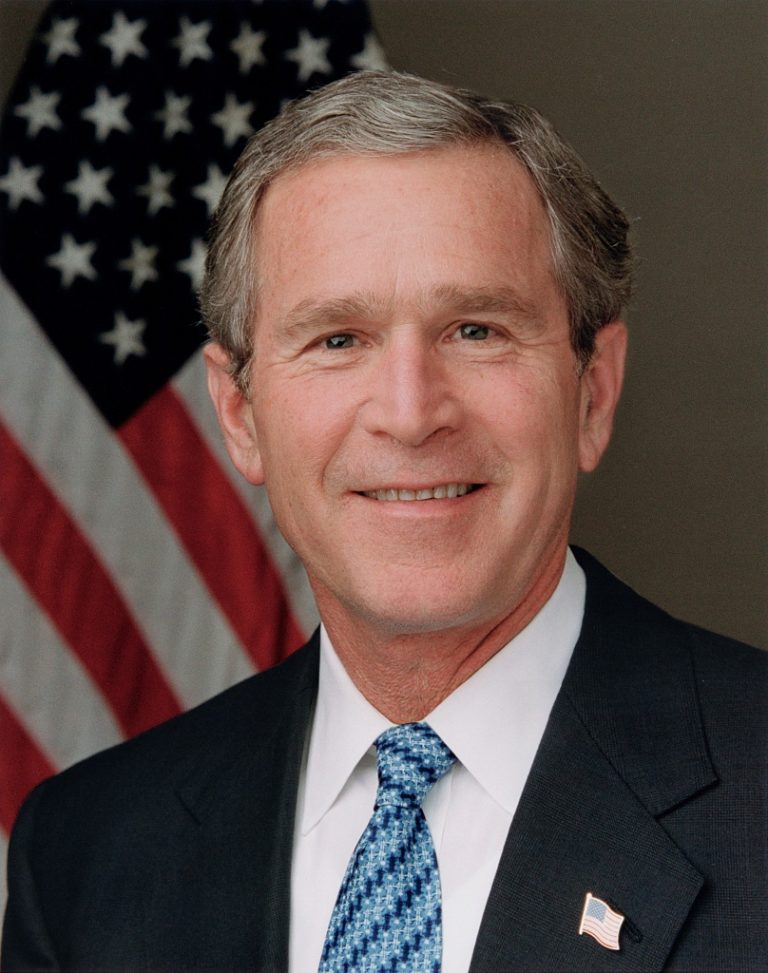

Clement Clarke Moore was capable of having fun, writing light verse, and loving his children. Was he also a liar?

Having attacked Moore’s personality, ideology, and parental style, in the end Foster challenges the man’s personal integrity as well. In a way, he needs to do so, since Moore did, after all, eventually have “The Night before Christmas” published under his own name, a circumstance that would seem to offer the most powerful evidence of his authorship. A man could be dour and child-hating without being a liar to boot–and a serious liar Moore must have been if he did not really write the poem.

At the end of his argument, Foster delivers a parting shot, proof positive that Moore falsely took credit for another work which was not his. Foster learned that Moore donated a book to the New-York Historical Society. The book, an 1811 treatise on the raising of Merino sheep, was originally written in French, and on the title page of the copy he donated, just beneath the words “translated from the French,” is a penned-in notation: “by Clement C. Moore, A.M.” But Foster found a copyright notice for this book, included only in a later bound-in appendix, showing that another man, one Francis Durand, “is also the book’s sole translator” (these are Foster’s words). Foster concludes, “Professor Moore does not just recycle a few borrowed phrases, as in his poetry–he lays claim to an entire book that was the work of another man.”

The charge will not stick. It is clear even to my own inexpert eye that the penned inscription “by Clement C. Moore, A.M.” is not written in Moore’s rather distinctive hand. Moreover, Moore was not in the habit of referring to his master’s degree when he signed his name. In all likelihood, the inscription was written by someone at the New-York Historical Society in recognition of Moore’s gift. It is no evidence that Moore tried to take credit for the translation. Charge dismissed.

Still, why the apparently erroneous attribution? While this question requires no answer here, the most likely one happens to shed light on a larger question: I believe that the attribution was correct: Moore did do the translation, perhaps together with Durand, and he never chose to take public credit for it. The reason is simple, and revealing: men of high social position often published their work anonymously in the early nineteenth century (Moore often did so himself), because public anonymity was often a sign of gentility. But it is easy to imagine that Moore was pleased with his work and he did not object to letting word of it become known to the small elite group who were his fellow members of the New-York Historical Society. (In fact, the copyright notice does not show that Francis Durand translated this treatise but only that he claimed legal rights to it–rights that Moore could easily have assigned to him in a display of noblesse, perhaps for collaborating in the translation. Furthermore, while the title page of the book indicates that it was “translated from the French,” it does not name a translator. Had Francis Durand really done that job himself, he could easily have said so on the title page–and he did not.) The whole inconsequential affair shows, again, not that Moore was a liar but that he was just what we already know him to have been–a patrician.

A similar dynamic was probably at play with “The Night before Christmas.” The poem first appeared in 1823, anonymously, in a newspaper in Troy, New York (there is no clear evidence how it got there, though legend has it that one of Moore’s relatives was responsible for copying the poem down after hearing Moore say it aloud to his family the year before). In 1829 that same Troy newspaper reprinted the poem, which by now had already begun to circulate widely around the country. The 1829 printing was again anonymous, but this time the newspaper’s editor added some tantalizing hints about the identity of the poem’s author: he was a New York City man “by birth and residence,” and “a gentleman of more merit as a scholar and writer than many of more noisy pretensions.” While keeping up the aura of genteel anonymity, these words pointed pretty clearly to Moore (Henry Livingston, who had died two years before, was neither a scholar nor a New Yorker), and it seems rather likely that Moore’s name had been cropping up for some time among people in his own circle. Moore was almost certainly becoming privately proud of what was far and away the most famous thing he had ever done. Eight years later, in 1837, a member of Moore’s circle publicly named him as the author; Moore did not object. Finally, in 1844, Moore used the rationale that his own children had pressed him to publish his collected poetry as an excuse to include the poem and thereby to openly acknowledge his authorship. (Moore’s children believed–and perhaps with very good reason–that their father had written “The Night before Christmas.”)

Assume for a moment that Foster is correct after all in his assessment of Moore’s personality. In that case–if the man was so curmudgeonly, prudish, and moralistic, so profoundly offended by frivolous poetry, that he would not have written “The Night before Christmas”–why would he have chosen to take public credit for it? If there was anything less likely than his writing such a thing (and doing so for wholly private use), surely it was choosing to name himself in print as its author–in a handsomely printed collection of his own poetry, no less. From Moore’s own perspective–though crucially not from ours, and we should be sure to make this distinction–such a thing could have brought him only discredit. Foster’s claim that Moore was incapable of writing the poem is incompatible with the fact that Moore was capable of claiming its authorship.

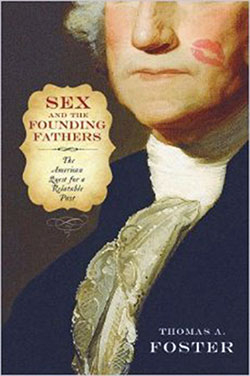

Clement Moore was no child-hating, mendacious curmudgeon. But to say that he was capable of writing light domestic verse is not to say that “The Night before Christmas” is nothing but a light-hearted children’s poem, a mere esprit in which the real man is nowhere to be discerned. There is in fact no reason why humorous works written for children may not also contain the seeds of serious adult concerns. Alice in Wonderland comes quickly to mind, of course, not to mention virtually any “fairy tale.” “The Night before Christmas” too is just such a work, a fact which strengthens the case for Moore’s authorship. Understanding this requires understanding the New York social world in which Moore lived, a world in which St. Nicholas was emerging as a real cultural presence in the first two decades of the nineteenth century.

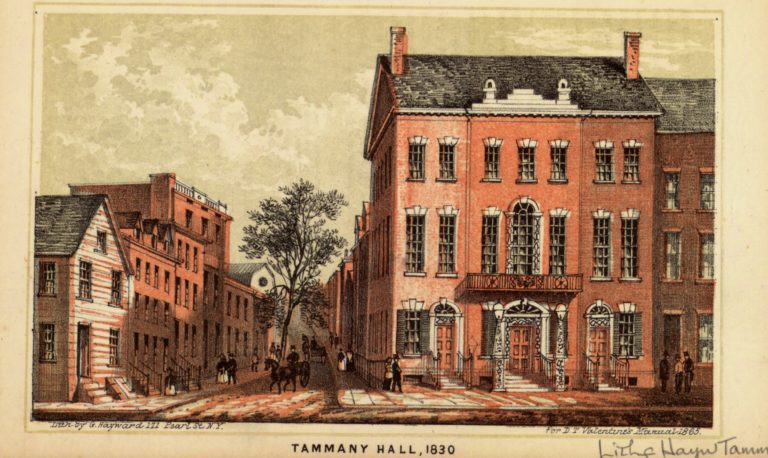

This was the world of self-dubbed “knickerbockers,” a group of men whose collective home was the New-York Historical Society, founded in 1804 by John Pintard. Pintard actually introduced St. Nicholas as the symbolic patron saint of the Historical Society, which held annual dinners on December 6, St. Nicholas Day. (According to the scholar who investigated this subject, before Pintard’s interventions there had been no evidence of Santa Claus rituals in the state of New York.) The most famous member of the New-York Historical Society was Washington Irving, who made much of St. Nicholas in his 1809 book Knickerbocker’s History of New York, which was actually published on St. Nicholas Day. It was Irving who popularized St. Nicholas in the 1810s. Clement Moore joined the New-York Historical Society in 1813.

For the Historical Society’s St. Nicholas Day dinner in 1810, John Pintard commissioned the publication of a broadside containing a picture of St. Nicholas in the form of a rather stern, magisterial bishop, bringing gifts for good children and punishments for bad ones. Two weeks later, and presumably in response to Pintard’s broadside, a New York newspaper printed a poem about St. Nicholas. Moore almost certainly knew of this poem; in fact, it is just barely possible that he wrote it. The poem is narrated by a child who is essentially offering a prayer to the stern saint.

The poem is in–what else?–anapestic tetrameter. It opens: “Oh good holy man! whom we Sancte Claus name, / The Nursery forever your praise shall proclaim.” It goes on to catalogue the presents St. Nicholas might be hoped to leave, followed by an entreaty that he not come for the purpose of punishment (“[I]f in your hurry one thing you mislay, / Let that be the Rod–and oh! keep it away.”) And it concludes with a promise of future good behavior:

Then holy St. Nicholas! all the year,

Our books we will love and our parents revere,

From naughty behavior we’ll always refrain,

In hopes that you’ll come and reward us again.

Like Clement Moore, the knickerbockers who brought St. Nicholas to New York were a deeply conservative group who loathed the democrats and the capitalists who were taking over their city and their nation. Washington Irving disdainfully summarized in the Knickerbocker History an episode which clearly represented to his readers the Jeffersonian Revolution of 1800: “[J]ust about this time the mob, since called the sovereign people . . . exhibited a strange desire of governing itself.” And in 1822 (a year before the first publication of “The Night before Christmas”), John Pintard explained to his daughter just why he was opposed to a new state constitution adopted that year, a constitution that gave men without property the right to vote: “All power,” Pintard wrote, “is to be given, by the right of universal suffrage, to a mass of people, especially in this city, which has no stake in society. It is easier to raise a mob than to quell it, and we shall hereafter be governed by rank democracy . . . Alas that the proud state of New York should be engulfed in the abyss of ruin.”

During these same years, Clement Moore’s large home estate (named Chelsea) was being systematically destroyed by the city of New York, divided up by right of eminent domain into a new series of numbered streets and avenues that were a product of the city’s rapid northward expansion. (Chelsea extended all the way from what is now called Eighteenth Street to Twenty-fourth Street, and from Eighth to Tenth Avenues–a large chunk of real estate indeed, and one that is known to this day as the Chelsea District.) In 1818, Moore published a tract protesting against New York’s relentless development. In that tract he expressed a fear that the city was in what he termed “destructive and ruthless hands,” the hands of men who did not “respect the rights of property.” He was pessimistic about the future: “We know not the amount nor the extent of oppression which may yet be reserved for us.”

“In the real world of New York, misrule came to a head at Christmastime.”

In short, both Moore himself and his fellow knickerbockers felt that they belonged to a patrician class whose authority was under siege. From that angle, the knickerbocker interest in St. Nicholas was part of a larger, ultimately quite serious cultural enterprise: forging a pseudo-Dutch identity for New York, a placid “folk” identity that could provide a cultural counterweight to the commercial bustle and democratic misrule of the early-nineteenth-century city. (Incidentally, Don Foster should be wary about taking Henry Livingston’s “Dutch” persona wholly at face value, as a lingering manifestation of traditional folk culture; I’m inclined to suspect it was highly self-conscious.) The best-known literary expression of this larger knickerbocker enterprise is Irving’s classic story “Rip Van Winkle” (published in 1819), the tale of a lazy but contented young Dutchman who falls asleep for twenty years and awakens to a world transformed, a topsy-turvy world in which he seems to have no place.

In the real world of New York, misrule came to a head at Christmastime. As I have shown in my book The Battle for Christmas, this season had traditionally been a time of carnival behavior, especially among those whom the knickerbockers considered “plebeians.” Bands of roving youths, lubricated by alcohol, went about town making merry, making noise, and sometimes making trouble. Ritual usage sanctioned their practice of stopping at the houses of the well-to-do and demanding gifts of food and especially drink–a form of trick-or-treat commonly known as “wassailing.” After 1800, this Christmas misrule took on a nastier tone, as young and alienated working-class New Yorkers began to use wassailing as a form of rambling riot, sometimes invading people’s homes and vandalizing their property. One particularly serious episode took place during the 1827 Christmas season; one newspaper reported it to have been the work of a mob that was not only “stimulated by drink” but also “enkindled by resentment.” The newspaper warned its readers not “to wink at such excesses, merely because they occur at a season of festivity. A license of this description will soon turn festivals of joy, into regular periods of fear to the inhabitants, and will end in scenes of riot, intemperance, and bloodshed.” (There is no evidence that Clement Moore’s Chelsea home was disturbed by roving gangs, despite the new cross-streeted vulnerability of the property, but in “A Trip to Saratoga” he noted that noisy drunken hotel guests often made “the sounds of strife or wassail, in the night.”)

Washington Irving and John Pintard were both nostalgic for the days when wassailing had been a more innocent practice, and both were concerned about the way Christmas had lately become a season of menace. Each, in his own way, engaged in an effort to reclaim the season. Irving wrote stories of idyllic English holiday celebrations (he did much of his research at the New-York Historical Society), and Pintard went about devising new seasonal rituals that were restricted to family and friends. His introduction of St. Nicholas at the Historical Society after 1804 was part of that effort.

And “The Night before Christmas,” published in 1823, became its apotheosis. What these enduring verses accomplished was to address all the problems of elite New Yorkers at Christmastime. Using the raw material already devised out of Dutch tradition by John Pintard and Washington Irving, the poem transformed stern and dignified St. Nicholas into a jolly old elf, Santa Claus, a magical figure who brought only gifts, no punishments or threats. Just as important, the poem provided a simple and effective ceremony that enabled its readers to restrict the holiday to their own family, and to place at its heart the presentation of gifts to their children–in a profoundly gratifying, ritual alternative to the rowdy street scene that was taking place outside. “The Night before Christmas” moved the Christmas gift exchange off the streets and into the house–a secure domestic space in which there really was “nothing to dread.” And don’t forget that in real life, prosperous people did have something to dread–after all, those wassailing plebeians might not be satisfied to remain outside.

“The Night before Christmas” contains a sly allusion to that possibility: for Santa Claus himself is a personage who breaks into people’s houses in the middle of the night at Christmastime. But of course this particular housebreaker comes not to take but togive–to wish goodwill without having received anything in return. “The Night before Christmas” raises the ever present threat–the “dread”–but only in order to defuse it, to offer jolly assurance that the well-being of the household will not be disturbed but only enhanced by this nocturnal holiday visitor.

Did Clement Clarke Moore write “The Night before Christmas”? I believe he did, and I think I have marshaled an array of good evidence to prove, in any case, that Moore had the means, the opportunity, and even the motive to write the poem. Like Don Foster’s, my evidence must necessarily be circumstantial, but I believe mine is better than his. Some of my evidence is quite straightforward. All of it is based on the belief that historical circumstance helped make Clement Moore a figure of greater complexity than either his admirers or his detractors have recognized, and that he might well have revealed that complexity in a poem he almost certainly did regard as nothing more than a throwaway children’s piece. But, then again, what more likely occasion for a curmudgeonly patrician to confront his inner demon?

Especially when he could turn him into a jolly old elf.

Further Reading:

Don Foster’s essay appears as chapter 6 of his book Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (New York, 2000). Section 3 of the present essay is based on chapters 1 and 2 of my book The Battle for Christmas (New York, 1996); see also Charles W. Jones, “Knickerbocker Santa Claus,” The New-York Historical Society Quarterly 38 (1954): 356-83. The only biography of Clement Clarke Moore, albeit hagiographic, is Samuel W. Patterson, The Poet of Christmas Eve: A life of Clement Clarke Moore, 1779-1863 (New York, 1956); see also Arthur N. Hosking, “The Life of Clement Clark Moore,” appended to a facsimile reprint of the 1848 edition of Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (New York, 1934). Another satirical account of a visit to Saratoga is James K. Paulding, The New Mirror for Travelers; and Guide to the Springs (New York, 1828); himself a knickerbocker, Paulding also wrote The Book of Saint Nicholas (New York, 1836). The transformation of New York City can be followed in Paul A. Gilje, The Road to Mobocracy: Popular Disorder in New York City, 1763-1834 (Chapel Hill, 1989); Raymond A. Mohl, Poverty in New York, 1783-1825 (New York, 1971); Christine Stansell, City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 1789-1860 (New York, 1986); and Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788-1850 (New York, 1984); see also Susan G. Davis, Parades and Power: Street Theatre in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1986). For the notion of “invented traditions” (such as St. Nicholas in New York), see Eric J. Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: 1983).

This article originally appeared in issue 1.2 (January, 2001).

Stephen Nissenbaum’s book The Battle for Christmas (1996) was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in history; he teaches history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.