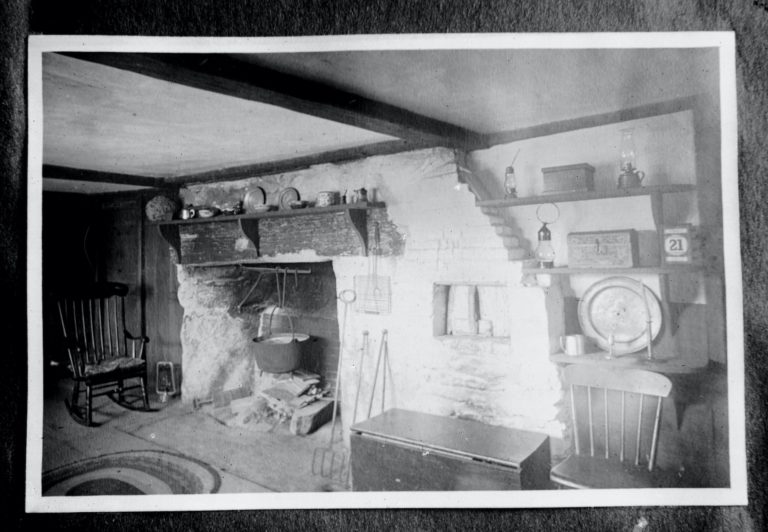

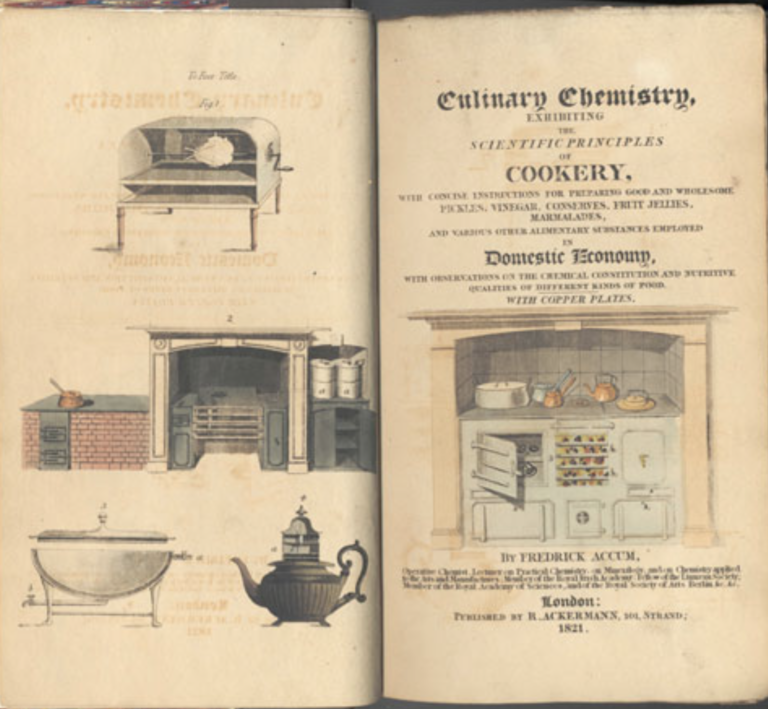

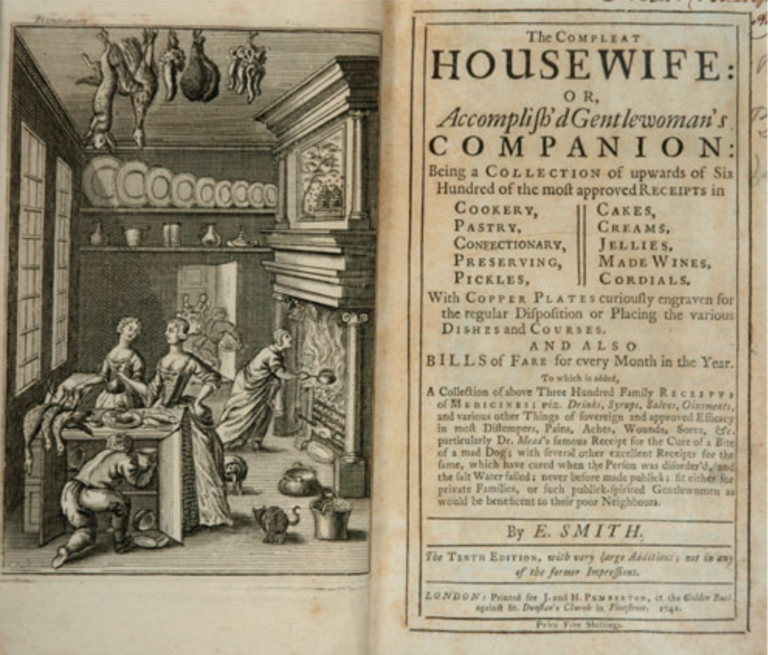

The following recipes have been extracted from assorted cookbooks published during the Age of Experiment. Most recipes predating 1840 were designed for hearthside cookery; those post-1840, for cookstove preparation. As you will see, they are facsimiles, reprinted here exactly as they were written for nineteenth-century cooks. The challenge and pleasure of updating them for the twenty-first century kitchen are yours. Bon appétit!

Soups

Black Bean Mock Turtle Soup

Take the usual quantity of beans (the Spanish, a black bean) wash them, put them into the pot with the proper quantity of water, boil them until thoroughly done, then dip the beans out of the pot and press them through a colander, return into the water of the pot in which the beans are boiled, the flour of the beans thus pressed through the colander, tie up some Thyme, put it in the pot, and let it simmer a few minuts, then boil a few eggs hard, take the shells off, quarter the eggs and put them into the soup, together with a sliced lemon, and season with pepper and salt and butter, and you will have a soup so nearly approaching the flavor of the real turtle soup, that few, except for the absence of the meat, would be able to distinguish the difference. Those who like wine in their soup, can, of course, add it, so as to suit their taste.

This bean is called the ‘Black Dwarf,’ and was we believe, introduced into our country by that friend of agriculture, Mr. George Law, of our city, to whom the farming public is indebted for many good things before and since. The American Farmer, 3, 2 (June 1848), p. 390.

Butter Bean Soup 1

Butter beans should be full grown, but tender. Hull them, rinse and boil them tender, in clear water, with a little salt. Thicken the soup with butter, flour, pepper and cream, and serve it up with toasts or crackers. Mrs. Lettice Bryan, The Kentucky Housewife (Cincinnati: Shepard & Stearns, 1839), p. 22

Butter Bean Soup 2

Boil a fat young fowl till about half done; then put in your butter beans, and boil them with the fowl till all are done, seasoning it sufficiently with salt, pepper and butter. Mash the beans to a pulp, make it into small cakes, and put over them yolk of egg and flour. Remove the skin from the fowl mince the breast and some of the other parts, and put them in the soup, with the cakes; stir in enough flour and cream to thicken it, boil it up, and serve it. Dried butter bean soup may be made in either of these ways, after parboiling them in clear water. Mrs. Lettice Bryan, The Kentucky Housewife (Cincinnati: Shepard & Stearns, 1839), p. 22.

Catfish Soup

An excellent dish for those who have not imbibed a needless prejudice against those delicious fish Take two large or four small white catfish that have been caught in deep water, cut off the heads, and skin and clean the bodies; cut each in three parts, put them in a pot, with a pound of lean bacon, a large onion cut up, a handful of parsley chopped small, some pepper and salt, pour in a sufficient quantity of water, and stew them till the fish are quite tender but not broke; beat the yolks of four fresh eggs, add to them a large spoonful of butter, two of flour, and half a pint of rich milk; make all these warm and thicken the soup, take out the bacon, and put some of the fish in your tureen, pour in the soup, and serve it up. Mrs. Mary Randolph, The Virginia Housewife: or, Methodical Cook (Baltimore: Plaskitt, Fite & Co., 1838), p. 19.

Cold Cherry Soup

Boil a pound of stoned cherries with sugar, until soft, and put by. Bruise the stones, and pour over them a quart of water, a piece of cinnamon, and some lemon-peel; let it boil for a quarter of an hour, add to it a bottle of wine and a half a pound of sugar, and let it cool; then pour this liquid over the boiled cherries and some broken crackers into the tureen. William Volmer, The United States Cook Book (Philadelphia: John Weick, 1859), p. 25.

To Make a Chowder

1st. Procure a hard-fleshed fish, like a striped bass—than which nothing is better—one of six pounds will be sufficient for an ordinary family. Clean the fish in the coldest well water; split it from head to tail, and cut it then into pieces, half as large as your hand.

2d. An old-fashioned round-bottomed pot is indispensable.

3d. Take half a pound of salt pork, slice it and fry it in the pot; then remove the pork, leaving the fat.

4th. Make a layer in the pot of pieces of fish; then season this with a little salt, red and black pepper, and a little (only a little,) ground cloves and mace, on this sprinkle a small quantity of chopped onions, and a part of the friend pork chopped or cut into fine pieces.

5th. Cover this with a layer of split crackers.

6th. Another layer of fish, seasoning, chopped onions, and pork, as above.

7th. Another layer of cracker, and so continue till all the fish is used, letting the top layer be of crackers.

8th. Pour into the pot just water enough to cover the whole, set it on the fire and let it simmer half an hour or so till the fish is tender to the touch of a fork. Great care should be taken that it does not come to a hard boil, but keep it at just the boiling point. Then removed the fish, crackers and all, with a skimmer, to a deep dish, leaving the gravy in the pot.

9th. Thicken the gravy with pounded crackers, add to it the juice of a lemon, half a tumblerful of good claret, and if it needs more seasoning, a little red and black pepper to your taste.

10th. Pour the gravy over the fish and crackers and all; garnish the dish with clices of lemon, serve warm, eat, and return thanks. American Farmer’s Magazine 12 (January 1859), 57-58.

Clam Chowder

Procure a bucket of clams and have them opened: then have the skin taken from them, the black part of their heads cut off, and put them into clean water. Next proceed to make your chowder. Take half a pound of fat pork, cut it into small thin pieces and try it out. Then put into the pot (leaving the pork and drippings in) about a dozen potatoes, sliced then some salt and pepper, and add half a gallon of water. Let the whole boil twenty minutes and while boiling put in the clams a pint of milk and a dozen hard crackers, split. Then take off your pot, let it stand a few minutes. Clams should never be boiled in a chowder more than five minutes; three is enough, if you wish to have them tender. If they are boiled longer than five minutes they become tough and indigestible as a piece of India rubber. Too much seasoning is offensive to many people, the ladies especially. Excursion Letters from Mr. [Nathan] Willis Number XIV, Home Journal 38, 188 (September 15, 1849), p. 2.

Fine Clam Soup

Take half a hundred or more small sand clams, and put them into a pot of hard-boiling water. Boil them about a quarter of an hour, or till all the shells have opened wide. Then take them out, and having removed them from the shells, chop them small and put them with their liquor into a pitcher. Strain a pint of the liquor into a bowl, and reserve it for the soup. Put the clams into a soup-pot, with a gallon of water, and half pint of the liquor; a dozen whole pepper-corns, half a dozen blades of mace; but no salt, as the clam liquor will be salt enough; add a pinto of grated bread-crumbs, and the crusts of the bread cut very small; also a tea-spoonful of sweet-marjoram leaves. Let the soup boil two hours. Then add a quarter of a pound of fresh butter, divided into half a dozen pieces, and each piece rolled slightly in flour. Boil it half an hour longer, and then about five minutes before you take up the soup, stir in the beaten yolks of three eggs.

As the flavour will be all boiled out of the chopped claims, it will be best to leave them in the bottom of the soup-pot, and not serve them up in the tureen. Press them down with a broad wooden ladle, so as to get as much liquor out of them as possible, while you are taking up the soup. This soup will be better still, if made with milk instead of water; milk being an improvement to all fish-soups. Miss Leslie, The Lady’s Receipt-Book (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1847), pp. 13-14.

Dixie Soup [Chicken & Oyster Soup]

Cut up a chicken and put it, with a sliced onion, into a soup pot; fry it brown in a little hot butter or lard; then pour on it 3 quarts of water, and boil it slowly until the meat separates from the bones. Skim off all grease, and remove the bones; add 1 pint of oyster liquor, and boil for 30 minutes; then add 1 quart of oysters. When the gills turn, stir 1 table-spoon of butter, rolled in flour, to thicken the soup. Put some nicely toasted bread, cut into squares, into the tureen; pour upon them the soup, and serve. Knuckle of veal or rabbits can also be prepared in this manner. Miss Tyson, The Queen of the Kitchen; a Collection of ‘Old Maryland’ Family Receipts for Cooking (Philadelphia: T. B. Petterson & Brothers, 1874), p. 93.

Duck Soup

Half roast a pair of fine large tame ducks; keeping them half an hour at the fire, and saving the gravy, the fat of which must be carefully skimmed off. Then cut them up; season them with black pepper; and put them into a soup-pot with four or five small onions sliced thin, a small bunch of sage, a thin slice of cold ham cut into pieces, a grated nutmeg, and the yellow rind of a lemon pared thin, and cut into bits. Add the gravy of ducks. Pour on, slowly, three quarts of boiling water from a kettle. Cover the soup-pot, and set it over a moderate fire. Simmer it slowly (skimming it well) for about four hours, or till the flesh of the ducks is dissolved into small shreds. When done, strain it through a sieve into a tureen over a quart of young green peas, that have been boiled by themselves. If peas are not in season, substitute half a dozen hard boiled eggs cut into round slices, white and yolk together.

If wild ducks are used for soup, three or four will be required for the above quantity. Before you put them on the spit to roast, place a large carrot in the body of each duck, to remove the sedgy or fishy taste. This taste will be all absorbed by the carrot, which, of course, must be thrown away. Miss Leslie, The Lady’s Receipt-Book (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1847), pp. 12-13.

Fish Stock

Take a pound of skate, four or five flounders, and two pounds of eels. Clean them well and cut them into piece: cover them with water; and season them with mace, pepper, salt, an onion stuck with cloves, a head of celery, two parsley-roots sliced, and a bunch of sweet herbs. Simmer an hour and a half closely covered, and then strain it off for use. If for brown soup, first fry the fish brown in butter, and then do as above. It will not keep more than two or three days. An Experienced Housekeeper, American Domestic Cookery (New York: Duyckinck, 1823), pp. 129-130.

Fish Chowder

Take a bass weighing four pounds, boil half an hour; take six slices raw salt pork, fry them till the lard is nearly extracted, one doz. Crackers soaked in cold water five minutes; put the bass into the lard, also the pieces of pork and crackers, add two onions chopped fine, cover close and fry for twenty minutes; serve with potatoes, pickles, apple sauce or mangoes; garnish with green parsley. Anon., The Cook Not Mad, or Rational Cookery (Watertown: Knowlton & Rice, 1831), p. 20.

Gumbo Soup, a favorite New Orleans Pottage

Take a fowl of good size, cut it up, season it with salt and pepper, and dredge it with flour. Take the soup kettle, and put in it a table spoonful of butter, one of lard, and one of onions chopped fine. Next fry the fowl till well browned and add four quarters of boiling water. The pot should now, being well covered, be allowed to simmer for a couple of hours. Then put in twenty or thirty oysters, a handful of chopped okra or gumbo, and a very little thyme, and let it simmer for half an hour longer. Just before serving it up, add about half a table spoonful of feelee powder. This soup is usually eaten with the addition of a little cayenne pepper, and is delicious. “Okra, and the Science of Soups,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, 3 (September 1847), p. 118.

Jerusalem Artichoke Soup

Have a knuckle of veal (weighing about five pounds) for dinner. When all have dined, return the bones into the stewpan, with the liquor in which it was boiled, a nice, white onion, and two turnips. Boil some Jerusalem artichokes in milk, (skim milk will do,) then beat up all with the liquor, which, of course, must be first strained, then thickened with a small quantity of flour rubbed smooth in a tea cup, with a little milk. Use white pepper for the seasoning, to keep the color pure. Mrs. J. C. Croly, Jennie June’s American Cookery Book (New York: Excelsior Publishing House, 1878), p. 29.

Excellent Lobster Soup

Take the meat from the claws, bodies, and tails, of six small lobsters; take away the brown fur, and the bag in the head: beat the fins, chine, and small claws in a mortar. Boil it very gently in two quarts of water, with the crumb of a French roll, some white pepper, salt, two anchovies, a large onion, sweet herbs, and a bit of lemon-peel, till you have extracted the goodness of them all. Strain it off. Beat the spawn in a mortar, with a bit of butter, a quarter of a nutmeg and a tea-spoonful of flour; mix it with a quart of cream. Cut the tails into pieces, and give them a boil up with the cream and soup. Serve with forcemeat balls made of the remainder of the lobster, mace, pepper, salt; a few crumbs, and an egg or two. Let the balls be made up with a bit of flour, and heated in the soup. An Experienced Housekeeper, American Domestic Cookery (New York: Duyckinck, 1823), p. 130.

Maigre, or Vegetable Gravy

Put into a gallon stewpan three ounces of butter; sit it over a slow fire; while it is melting, clice four ounces of onion; cut in small pieces one turnip, one carrot, and a head of celery; put them in the stewpan, cover it close, let it fry till they are lightly browned; this will take about twenty-five minutes: have ready, in a saucepan, a pint of pease, with four quarts of water; when the roots in the stewpan are quite brown, and the pease come to a boil, put the pease and water to them; put it on the fire; when it boils, skim it clean, and put in a crust of bread about as big as the top of a twopenny loaf, twenty-four berries of all-spice, the same of black pepper, and two blades of mace; cover it close, let it simmer gently for one hour and a half; then set it from the fire for ten minutes; then pour it off very gently (so as not to disturb the sediment at the bottom of the stewpan) into a large basin; let it stand (about two hours) till it is quite clear: while this is doing, shred one large turnip, the red part of a large carrot, three ounces of onion minced and one large head of celery cut into small bits; put the turnips and carrots on the fire in cold water, let them boil five minutes, then drain them on a sieve, then pour off the soup clear into a stewpan, put in the roots, put the soup on the fire, let it simmer gently till the herbs are tender (from thirty to forty minutes), season it with salt and a little cayenne, and it is ready. You may add a table-spoonful of mushroom ketchup. You will have three quarts of soup, as well colored, and almost as well flavored, as if made with gravy meat. To make this it requires nearly five hours. To fry the herbs requires twenty-five minutes; to boil all together, one hour and a half; to settle, at the least, two hours; when clear, and put on the fire again half an hour more. A Boston Housekeeper, The Cook’s Own Book, and Housekeeper’s Register (Boston: Munroe & Francis, 1840), p. 206.

New England Chowder 1

Have a good haddock, cod, or any other solid fish, cut it in pieces three inches square, put a pound of fat salt pork in strips into the pot, set it on hot coals, and fry out the oil. Take out the pork, and put in a layer of fish, over that a layer of onions in slices, then a layer of fish with strips of fat salt pork, then another layer of onions, and so on alternately until your fish is consumed. Mix some flour with as much water as will fill the pot; season with black pepper and salt to your taste, and boil it for half an hour. Have ready some crackers soaked in water till they are a little softened; throw them into your chowder five minutes before you take them up. Serve in a tureen. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Ellet, The Practical Housekeeper (New York: Stinger & Townsend, 1857), p. 187.

New England Chowder 2

Cover the bottom of a pot with slices of boiled salt pork, with a little onions; on this place a layer of fish in large pieces, season with pepper, and cover it with a layer of biscuit soaked in milk, and a layer of sliced potatoes. Put above this another layer of pork, as before, with fish, &c., the biscuit being on the top of all. Pour in a pint and a half of water, cover, and boil it slowly an hour; then skim and turn it into a deep dish. Thicken the gravy with butter rolled in flour, and parsley. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Ellet, The Practical Housekeeper (New York: Stinger & Townsend, 1857), p. 187.

Okra Soup

The pods are of a proper size when two or three inches long, but may be used while they remain tender; if fit for use, they will snap asunder at the ends, but if they merely bend, they are too old, and must be rejected; for a few of such pods will spoil a dish of soup.

Take one peck, cut them across into very thin slices, not exceeding one-eight of an inch in thickness, but as much thinner as possible, as the operation is accelerated by their thinness; to this quantity of okra add about one-third a peck of tomatoes, which are first pealed and cut into pieces. This quantity can be increased or diminished, as may suit the taste of those for whom it is intended. A coarse piece of beef (a shin is generally made use of) is placed in a digester, with about two and a half gallons of water, and a very small quantity of salt. It is permitted to boil for a few moments, when the scum is taken off, and the okra and tomatoes thrown in.

These are all the ingredients absolutely necessary, and the soup thus made is remarkably fine. We, however, usually add some corn cut off from the tender roasting ears: the grains from three ears will be enough for the above quantity: we sometimes take about half a pint of Lima beans. Both of these improve the soup, but not so much as to make them indispensable; so far from it, that few add them. The most material thing to be attended to is the boiling, and the excellence of the soup depends almost entirely on this being faithfully done: for, if it be not boiled enough, however well the ingredients may have been selected, the soup will be very inferior, and give little idea of the delightful flavor it possesses when properly done. I have already directed that the ingredient be placed in a digester. This is decidedly the best vessel for boiling this, or any other soup in, but should there be no digester, then an earthen pot should be prepared; but on no account make use of an iron one, as it would turn the whole soup of a black color; the proper color being green, colored with the rich yellow of the tomatoes.

The time which is usually occupied in boiling okra soup is five hours. We put it on at 9 a.m, and take it off about 2 p.m., during the whole of which time it is kept boiling briskly; the cook at the same time stirring it frequently, and mashing the different ingredients. By the time it is taken off, it will be reduced to about one half; but as on the operation of the boiling being well and faithfully executed depends its excellence, I will state the criterion by which this is judged of:—the meat separates entirely from the bone, being done to rags, the whole appears as one homogenous mass, in which none of the ingredients are seen distinct, the object of this long boiling being thus to incorporate them. Its consistence should be about that of thick porridge. Mrs. Mary L. Edgeworth, The Southern Gardener and Receipt-Book (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1860), pp. 135-136.

Pepper-Pot

To three quarts of water put vegetables according to the season; in summer peas, lettuce, and spinach: in winter, carrots, turnips, celery: and onions in both. Cut small, and stew with two pounds of neck of mutton, or a fowl, and a pound of pickled pork, in three quarts of water, till quite tender.

On first boiling, skim. Half an hour before serving, add a lobster, or crab, cleared from the bones. Season with salt and Cayenne. A small quantity of rice should be put in with the meat. Some people choose very small suet dumplings boiled with it. Should any fat rise, skim nicely, and put half a cup of water with a little flour.

Pepper-pot may be made of various things, and is understood to be a due proportion of fish, flesh, fowl, vegetables, and pulse. An Experienced Housekeeper, American Domestic Cookery (New York: Duyckinck, 1823), p. 126.

Red Pea Soup

One quart of peas, one pound of bacon, (or a hambone,) two quarts of water, and some celery, chopped; boil the peas, and, when half done, put in the bacon; when the peas are thoroughly boiled, take them out and rub them through a cullender or coarse sieve; then put the pulp back into the pot with the bacon, and season with a little pepper and salt, if necessary. If the soup should not be thick enough, a little wheat flour may be stirred in. Green peas may be used instead of the red pea. [Sarah Rutledge], The Carolina Housewife, or House and Home: by a Lady of Charleston (Charleston: W. R. Babcock & Co., 1847), p. 44.

Squirrel Soup

Take two fat young squirrels, skin and clean them nicely, cut them into small pieces, rinse and season them with salt and pepper, and boil them till nearly done. Beat an egg very light, stir it into half a pint of sweet milk, add a little salt, and enough flour to make it a stiff batter, and drop it by small spoonfuls into the soup, and boil them with the squirrels till all are done. Then stir in a small lump of butter, rolled in flour, a little grated nutmeg, lemon and mace; add a handful of chopped parsley and half a pint of sweet cream; stir it till it comes to a boil, and serve it up with some of the nicest pieces of the squirrels. Soup may be made in this manner of small chickens, pigeons, partridges and pheasants. Mrs. Lettice Bryan, The Kentucky Housewife (Cincinnati: Shepard & Stearns, 1839), p. 14.

Turtle Soup

Your turtle must be cleaned and prepared for the soup the day before you make it. Let the meat lie in weak salt water all night; early in the morning put it on the fire, about two gallons of water to a moderate sized turtle. Let it boil steadily but very slowly about four hours. Then put two potatoes, two small onions, one turnip and one carrot, all cut up very small, (these should be put in a cloth,) and let them boil until you put in the thickening. A tea-spoonful of cloves and as much ground black pepper, if not strong, a small table-spoonful. A tea-spoonful cayenne pepper, a table-spoonful of salt and the same of sweet marjoram, summer savory and thyme. If this is not enough to your taste, add more, two middle sized nutmegs. Boil all these until the soup is reduced one-half; then take out the cloth of vegetables and the turtle, and pick the latter clean, cut it into pieces large enough to eat with your soup, and return it to the pot, and afterwards mix three or four table-spoonsful of browned flour, with half a pound of butter; add this to the soup-let this be very smooth, or your soup will be covered with small black floating particles. Put two table-spoonsful of catsup and one-half pint of white wine. These last must be to your taste. In making turtle soup the lower shell should be boiled with the soup.

With [turtle] soup have always forcemeat balls; to make which take a pound and a half of veal not cooked, chop it fine, put a small quantity of beef, salt, some crumbs of bread, say half as much as meat-season the mixture highly with sage, sweet herbs and pepper, nutmeg and salt, roll the balls round and then flatten them and fry them in butter a light brown, and when the soup is ready to be served drop them in: either celery tops or parsley in small quantity is an improvement to the soup; they must be cut very small.

A lady. Southern Planter 4, 9 (September 1844), p. 203.

Fish and Seafood

Cat Fish

Cut each fish in two parts, down the back and stomach; take out the upper part of the back bone next the head; wash and wipe them dry, season with cayenne pepper and salt, and dredge flour over them; fry them in hot lard of a nice light brown. Some dress them like oysters; they are then dipped in beaten egg and bread crumbs and fried in hot lard. They are very nice dipped in beaten egg, without the crumbs, and fried. Lady of Philadelphia, The National Cook Book (Philadelphia: Hayes & Zell, 1856), p. 27.

Clam Bake, Steamer, or Bake Out

There is an Indian feast, quite common on the sea shore, that is known by either or all of these names. The Barnstable (Mass.) Patriot says it is got up in this wise:

It is prepared by first laying a bed of stone six or eight feet square, on which a fire is built and kept burning until the stones are red hot; a layer of wet sea weed is then thrown upon them and upon the sea weed a layer of quahaugs or clams. Over these is placed another layer of wet sea weed; on this layer, fish is laid stuffed and wrapped in cloths; and after another layer of sea weed vegetables may be put, or they may be placed between the fish and quahaugs. Over the whole is thrown a thick layer of sea weed which keeps in the steam which is generated by the heat of the stones, and which thoroughly penetrates the whole mass. In a short time the ‘bake’ is opened and all the culinary preparations are found completed ‘to a charm’ and ready for the table. In this way and with little trouble or time, a rich feast may be served for a large company. The Indians doubtless prepared their public dinners in this summary mode, and it is from them that their white brethren are indebted for this art in cookery. There is another way for preparing shell fish, probably derived from the same source, that is common on festive occasions in the villages on the south side of this town. It is called a ‘roast nut’ and is prepared by placing a large quantity of clams of quahaugs on the ground, joint downwards, and placing over them some light dry brush, which is set on fire and soon causes the clams or quahaugs to open their wide mouths just far enough to secure the prize within, without losing the delicious water. They are then taken up and are ready to serve. Thus a very large party may be provided with a dish of clams or quahaugs at the shortest notice in the most primitive style. Niles’ Weekly Register 2, 23 (August 5, 1837), 356.

To Fry Soft Shell Clams

When taken from the shell, and the black skin taken off, wash them in their own liquor, and lay them on a thickly folded clean cloth, to dry out the moisture; then have a pan of hot lard and butter, equal parts, roll the clams well in flour, and fill the pan, let them fry until one side is a fine brown, and before turning the other side, dredge it well with flour; serve with their own gravy. Grated horse-radish moistened with vinegar, to eat with them, and plain boiled or mashed potatoes. In city markets they will be found ready opened and cleaned. Mrs. T. J. Crown, Every Lady’s Cook Book (New York: Kiggins & Kellogg, 1854), p. 86.

Baked Cod

A fish weighing six or eight pounds is a good size to bake; it should be cooked whole to look well. Make a dressing of bread-crumbs, pepper, salt, parsley, and onion, and a little salt pork chopped fine; mix this up with one egg, fill the body, sew it up, lay it into a large pan; lay it across some strips of salt pork to flavor it; put one pinto of water and a little salt into the pan; bake it an hour and a half; baste it often with butter and flour. Dollar Monthly 20, 2 (August 1864), 156.

Slices of Cod-fish fried

Cut the middle or tail of the fish into slices nearly an inch thick, season them with salt and white pepper or Cayenne, flour them well, and fry them of a clear equal brown on both sides; drain them on a sieve before the fire, and serve them on a well-heated napkin, with plenty of crisped parsley round them. Or, dip them into beaten egg, and then into fine crumbs mixed with a seasoning of salt and pepper (some cooks add one of minced herbs,) before they are fried. Send melted butter and anchovy sauce to tabe with them. From 8 to 12 minutes to fry.

Obs.—This is a much better way of dressing the thin part of the fish than boiling it, and as it is generally cheap, it makes thus an economical, as well as a very good dish: if the slices are lifted from the frying-pan into a good curried gravy, and left in it by the side of the fire for a few minutes before they are sent to table, they will be found excellent—would be quite spoiled, if they are boiled with the fish. Garnish the dish with slices of hard boiled eggs, and serve with egg-sauce. Sarah Josepha Hale, Mrs. Hale’s New Book of Cookery (New York: H. Long & Brother, 1852), p. 35.

Crab Patties

Boil hard crabs, clean them nicely and pick out the white meat; season them with butter, pepper, and salt, and hard boiled yolk of egg grated; put in a few bread crumbs, give the mixture one boil, and fill crusts baked in patty-pans. Mrs. Sarah A. Elliott, Mrs. Elliott’s Housewife (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1870), p. 35.

Lobster Salad

With a lobster weighing two pounds in the shell, cut one large head of fresh lettuce. Then, for the dressing, mix 6 table-spoonsful of olive oil, 6 tablespoonsful of vinegar, 2 table-spoonsful of sugar, 2 tea-spoonfuls of mustard, 1 tea-spoonful of salt, and 2 hard-boiled eggs. The mustard may be used either dry or wet, and should be rubbed with the oil before the vinegar and other ingredients are added. All of the articles must be of good quality, especially the oil; and then the preparation is delicious. Scientific American7, 8 (August 23, 1862), p. 117.

Mackerel Boiled

This fish loses its life as soon as it leaves the sea, and the fresher it is the better. Wash and clean them thoroughly (the fishmongers seldom do this sufficiently) put them into cold water with a handful of salt in it; let them rather simmer than boil; a small mackerel will be done enough in about a quarter of an hour; when the eye starts and the tail splits, they are done; do not let them stand in the water a moment after; they are so delicate that the heat of the water will break them. Flag of our Union 13, 23 (June 5, 1858), p. 183.

To stew Muscles [Mussels]

Open them, put them into a pan with their own liquor, to which add a large onion and some parsley with 2 table-spoonful of vinegar; roll a piece of butter in flour, beat an egg, and add it to the gravy, warming the whole up very gradually. Sarah Josepha Hale, Mrs. Hale’s New Book of Cookery (New York: H. Long & Brother, 1852), p.64.

Best Pickled Oysters

Take fine large oysters, put them over the fire with their own liquor, add to them a bit of butter, and let them simmer until they are plump and white; when they are so, take them up with a skimmer, have a large napkin folded, lay the oysters, each spread nicely out, on it; then take of the oyster liquor and vinegar equal parts—enough to cover the oysters, have a large stone pot or tureen, put in a layer of oysters, lay over it some whole pepper, allspice and cloves, and some ground mace, then add another layer of oysters, then more spice, and then a layer of oysters, and spice, until all are done; then pour over the oyster liquor and vinegar, let them stand one night, and they are done—the vinegar and liquor must be warm. Oysters prepared in this way, are delicious. American Farmer, and Spirit of the Agricultural Journals of the Day 1, 7 (Baltimore January 1846), 22.

Oyster Sausages

Shred very small a pound of the lean of a leg of mutton, and two pounds of beef suet; in larger bits, a pint and half of oysters; and very small, half a handful of sage, or savory. Mix all together with the liquor of the oysters; season it with pepper and salt, adding half a dozen pounded cloves, and a blade or two of beaten mace; break among it three eggs; and work up the whole with grated bread crumb. Make them up as they are wanted, either in skins or cakes, and fry them in butter. Priscilla Homespun, The Universal Receipt Book (Philadelphia: Isaac Riley, 1818), p. 67.

To Fry Perch

Small perch should be fried whole. Scale and clean them immediately after they are killed; rinse them clean in two or three waters, wipe them dry with a cloth, season them with salt and pepper, and sprinkle on them a little flour or fine Indian meal. Put some lard into a frying-pan, set it on the fire, and when it boils up, and then becomes still, put in your fish; turn them over once, but do not break them. As soon as they are a light brown and crisp on both sides, serve them up. Send with them to table a boat of plain melted butter, to be seasoned with catchup, &c., as may be preferred. Large black perch may be fried in this manner, having them first split in two. Mrs. Lettice Bryan, The Kentucky Housewife (Cincinnati: Shepard & Stearns, 1839), p. 149.

To Bake a Rock Fish

Rub the fish with salt, black pepper, and dust of cayenne, inside and out; prepare a stuffing of bread and butter, seasoned with pepper, salt, parsley and thyme; mix an egg in it, fill the fish with this, and sew it up or tie a string round it; put it in a deep pan, or oval oven and bake it as you would a fowl. To a large fish add half a pint of water; you can add more for the gravy if necessary; dust flour over and baste with butter. Any other fish can be baked in the same way. A large one will bake slowly in an hour and a half, small ones in half an hour. Elizabeth E. Lea, Domestic Cookery, Useful Receipts, and Hints to Young Housekeepers (Baltimore: Cushings & Bailey, 1859), p. 35.

To Cook Shad

With iron the shad should never come in contact. A piece of planed plank, two feet long and one foot wide, with a skewer to impale the fish upon it, are all the culinary implements required. A fire of glowing coals, in front of which the shad is placed, gives you a shad cooked as shad should be. Apicus himself could desire nothing more delicious. Ballou’s Dollar 12, 1 (July 1860), p. 88.

Sheep’s-Head

This delicious fish is finer in the Norfolk, Virginia, market than any part of our country, and will not bear transportation without being packed in ice. After the fish is nicely cleaned and rinsed in two waters, put it on a fish-slice over a boiler of water, cover it and let it steam till perfectly done. When ready to serve, put in a dish with butter sauce poured over it. Garnish it with hard boiled eggs, cut in round slices, and curled parsley, and have butter sauce in the tureen to serve with it. Odenheimer, Worcester, or tomato sauce as an accompaniment. Mrs. Sarah A. Elliott, Mrs. Elliott’s Housewife (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1870), pp. 24-25.

Shrimp Pie

To two quarts of peeled shrimps add two tablespoonfuls of butter, half a pint of tomato catsup, half a tumbler of vinegar; season high with black and cayenne pepper; salt to taste; put into an earthen dish; strew grated biscuit, or light bread crumbs very thickly over the top; bake slowly half an hour. This may be varied by using Irish potatoes boiled and mashed, in place of the bread crumbs; or use a layer of shrimps, then macaroni, previously soaked in hot sweet milk. Mrs. A. P Hill, Mrs. Hill’s New Cook Book (New York: Carleton, 1872), p. 44.

Stewed Fish, Hebrew Fashion

Take three or four parsley-roots, cut them into long thin slices, and two or three onions also sliced, boil them together in a quart of water until quite tender; then flavor it with ground white pepper, nutmeg, mace, and a little saffron, the juice of two lemons, and a spoonful of vinegar. Put in the fish, and let it stew for twenty, or thirty minutes; then take it out, strain the gravy, thicken it with a little flour and butter, have balls made of chopped fish, bread-crumbs, spices, and the yolk of one or two eggs mixed up together, and drop them into the liquor. Let them boil, then put in the fish, and serve it up with the balls and parsley-roots. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Ellet, The Practical Housekeeper (New York: Stinger & Townsend, 1857), p. 214.

Fowls

To roast Wild Fowl

The flavour is best preserved without stuffing. Put pepper, salt, and piece of butter, into each. Wild fowl require much less dressing than tame: they should be served of a fine colour, and well frothed up. A rich brown gravy should be sent in the dish: and when the breast is cut into slices, before taking off the bone, a squeeze of lemon, with pepper and salt, is a great improvement to the flavour. To take off the fishy taste which wild fowl sometimes have, put an onion, salt, and hot water into the dripping-pan, and baste them for the first ten minutes with this; then take away the pan, and baste constantly with butter. An Experienced Housekeeper, American Domestic Cookery (New York: Duyckinck, 1823), p. 117.

Duck

Clean and wipe dry your duck; prepare the stuffing thus; chop fine and throw into cold water three good sized onions; rub one large spoonful of sage leaves, add two ditto of bread crumbs, a piece of butter the size of a walnut, and a little salt and pepper, and the onions drained. Mix these well together, and stuff the duck abundantly. Always keep on the legs of a duck; scrape and clean the toes and legs, and truss them against the sides. The duck should be kept a few days before cooking to become tender. Three quarters of an hour is generally enough for an ordinary sized duck. Dredge and baste like a turkey. A nice gravy is made by straining the drippings; skim off all the fat; then stir in a spoonful of browned flour, a teaspoonful of mixed mustard, and wine glass full of claret; simmer this for ten minutes. Serve hot. With the duck currant jelly is necessary. A Practical Housekeeper, Cookery as it Should Be (Philadelphia: Willis P. Hazard, 1856), p. 53.

Canvasback Duck

Of the two dozen species of American wild-ducks, none has a wider celebrity than that known as the canvas-back; even the eider-duck is less thought of, as the Americans care little for beds of down. But the juicy, fine flavored flesh of the canvas-back is esteemed by all classes of people; and epicures prize it above that of all other winged creatures, with the exception, perhaps, of the reed-bird or rice-bunting, and the prairie-hen. These last enjoy a celebrity almost, if not altogether equal. The prairie-hen, however, is the bon morceau of western epicures; while the canvas-back is only to be found in the great cities of the Atlantic. The reed-bird—the American representative of the ortolan—is also found in the same markets with the canvas-back. The flesh of all three of these birds—although the birds themselves are of widely different families—is really of the most kind; it would be hard to say which of them is the greatest favorite. The canvas-back is not a large duck, rarely exceeding three pounds in weight. Its color is very similar to the pochard of Europe; its head is a uniform deep chestnut, its breast black; while the back and upper part of the wings present a surface of bluish-gray, so lined and mottled as to resemble—though very slightly, I think—the texture of canvas; hence the trivial name of the bird. It is the roots of the wild celery that the flesh of the canvas-back owes it esteemed flavor, causing it to be in such demand that very often a pair of these ducks will bring three dollars on the markets of New York and Philadelphia. Littell’s Living Age 3, 490 (October 8, 1853), p. 86.

Chickens Fried in Batter

Make a batter of two eggs, a tea-cup of milk, a little salt, and thickened with flour; have the chickens cut up, washed and seasoned; dip the pieces in the batter separately, and fry them in hot lard; when brown on both sides, take them up on a dish, and make a gravy . . . Lard fries much nicer than butter, which is apt to burn. Elizabeth E. Lea, Domestic Cookery, Useful Receipts, and Hints to Young Housekeepers (Baltimore: Cushings & Bailey, 1859), p. 27.

Chicken Corn Pie

First, prepare two chickens as for frying, then put them down and let them stew in a great deal of good, rich highly seasoned gravy until they are just done. Then, have ready picked two dozen ears of corn; take a very sharp knife and shave them down once or twice, and then scrape the heart out, with the rest already shaved down; then get a baking pan (a deep one,) and place a layer of the corn on the bottom of the pan or dish, then a layer of the chicken, with some of the gravy, and then a layer of the corn, and so on, until you get all of the chicken in. Then cover with the corn, and pour in all the gravy, and put a small lump of butter on the top, and set it to baking in not a very hot oven. It does not take long to cook; as soon as the corn is cooked, it will be ready to send to the table. It can either be sent in the pan it is baked in, or turned out into another dish. There must be a great deal of gravy, or it will cook too dry. Saturday Evening Post (September 26, 1857), p. 4.

Fowl Pillau

Put one pound of rice into a frying pan with two ounces of butter, which keep moving over a slow fire, until the rice is lightly browned; then have ready a fowl trussed as for boiling, which put into a stewpan, with five pints of good broth; pound in a mortar about forty cardamom seeds with the husks, half an ounce of coriander seeds, and sufficient cloves, allspice, mace, cinnamon, and peppercorns, to make two ounces in the aggregate; which tie up tightly in a cloth, and put into the stewpan with the fowl; let it boil slowly until the fowl is nearly done; then add the rice, which let stew until quite tender and almost dry; have ready four onions, which cut into slices the thickness of half crown pieces; sprinkle over with flour, and fry, without breaking them, of a nice brown color; have also six thin slices of bacon, curled and grilled, and two eggs boiled hard; lay the fowl upon your dish, which cover over with the rice, forming a pyramid; garnish with bacon, fried onions, and the hard-boiled eggs cut into quarters, and serve very hot. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Ellet, The Practical Housekeeper (New York: Stinger & Townsend, 1857) p. 362.

Quails Cured in Oil

Procure a sufficient number of fine, plump quails. Pluck them, draw them, clean them thoroughly, cut them open so that they will lie flat, as broiling, and rub them over with salt. Let them lie in the salt, turning them every morning, for three days. Let them dry; and then pack them down close in a stone jar, covering each layer of quails tightly with fresh gathered vine leaves. Fill the jar with pure salad oil, and cover it securely with bladder, so as quite to exclude the air. When they are wanted, take them out and broil them. They make a delicious dish for breakfast. S. Annie Frost, The Godey’s Lady’s Book Receipts and Household Hints (Philadelphia: Evans, Stoddart & Co., 1870), p. 136.

Meat

To broil Beef Steaks

The steaks should be from half to three-quarters of an inch thick, equally sliced, and freshly cut from the middle of a well kept, finely grained, and tender rump of beef. They should be neatly trimmed, and once or twice divided, if very large. The fire must be strong and clear. The bars of the gridiron should be thin, and not very close together. When they are thoroughly heated, without being sufficiently burning to scorch the meat, wipe and rub them with fresh mutton suet; next pepper the steaks slightly, but never season them with salt before they are dressed; lay them on the gridiron, and when done on one side, turn them on the other, being careful to catch, in the dish in which they are to be sent to table, any gravy which may threaten to drain from them when they are moved. Let them be served the instant they are taken from the fire; and have ready at the moment, dish, cover, and plates, as hot as they can be. From 8 to 10 minutes will be sufficient to broil steaks for the generality of eaters, and more than enough for those who like them but partially done.

Genuine amateurs seldom take prepared sauce or gravy with their steaks, as they consider the natural juices of the meat sufficient. When any accompaniment to them is desired, a small quantity of choice mushroom catsup may be warmed in the dish that is heated to receive them; and which, when the not very refined flavor of a raw eschalot is liked, as it is by some eaters, may previously be rubbed with one, of which the large end has been cut off. A thin slice or two of fresh butter is sometimes laid under the steaks, where it soon melts aand mingles with the gravy which flows from them. The appropriate tureen sauces for broiled beef steaks are onion, tomato, oyster, eschalot, hot horse-radish, and brown cucumber, or mushroom sauce. Sarah Josepha Hale, Mrs. Hale’s New Book of Cookery (New York: H. Long & Brother, 1852), pp. 88-89.

Beef a-la-mode (a Philadelphia Receipt)

Cut the bone out of a round of fresh beef, and put into several incisions a dressing made of bread-crumbs, sweet herbs, and two small onions, chopped fine, with seasoning of salt, pepper, mace, and butter. Lard the beef, and fasten up the slits, and tie it firmly with tape.

Put into a kettle a pint and a half of water, with a few slices of pork; and put in the beef, stuck with a few cloves; cover closely, and bake it several hours. When it is cooked through, dish it and pour over the gravy, which may be increased in quantity by the addition of a little boiling water, and flour to thicken it, with a spoonful of brown sugar, and a glass of wine. Serve this gravy in a tureen, moistening the meat with it, and garnishing with sliced carrots and beets, and parsley or celery. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Ellet, The Practical Housekeeper (New York: Stinger & Townsend, 1857), p. 264.

Jerking Meat

So pure is the atmosphere, in the interior of our continent that fresh meat may be cured, or jerked, as it is termed in the language of the prairies, by cutting it into strips about an inch thick, and hanging it in the sun, where in a few days it will dry so well that it may be packed in sacks, and transported over long journeys without putrefying.

When there is not time to jerk the meat by the slow process described, it may be done in a few hours by building an open frame-work of small sticks about two feet above the ground, placing the strips of meat upon the top of it, and keeping up a slow fire beneath, which dries the meat rapidly.

Salt is never used in this process, and is not required, as the meat, if kept dry, rarely putrifies. Spirit of the Times, 29, 42 (November 26, 1859), 497.

Veal Sweet-Bread

Trim a fine sweet-bread; parboil it for five minutes, and throw it into a basin of cold water. Roast it plain, or beat up the yolk of an egg, and prepare some fine bread crumbs. When the sweet-bread is cold, dry it thoroughly in a cloth; run a skewer through it; egg it with a paste-brush, powder it well with bread crumbs, and roast it. For sauce, fried bread crumbs round it, and melted butter, with a little mushroom catsup and lemon-juice, or serve them on buttered toast, garnished with egg sauce or with gravy. S. Annie Frost, The Godey’s Lady’s Book Receipts and Household Hints (Philadelphia: Evans, Stoddart & Co., 1870), p. 116-117.

Frogs

This ugly, noisy animal is considered equal to young chicken by some epicures, and I give a receipt from early recollection when my father enjoyed them alone. Take the hind legs of the large bull-frog, skin them and throw them in boiling water and let them remain ten minutes, then put them in cold water to cool, wipe them dry, sprinkle a little salt and corn meal over and drop them in hot lard to fry until a light brown. Mrs. Sarah A. Elliott, Mrs. Elliott’s Housewife (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1870), p. 40.

Lamb Chops

Take a loin of lamb, cut chops from it half an inch thick, retaining the kidney in its place; dip them into egg and bread crumbs, fry and serve with fried parsley. When chops are made from a breast of lamb, the red bone at the edge of the breast should be cut off, and the breast parboiled in water or broth, with a sliced carrot and two or three onions, before it is divided into cutlets, which is done by cutting between every second or third bone, and preparing them, in every respect, as the last. If house-lamb steaks are to be done white-stew them in milk and water till very tender, with a bit of lemon-peel, a little salt, some pepper and mace. Have ready some veal gravy and put the steaks into it; mix some mushroom-powder, a cup of cream, and the least bit of flour; shake the steaks in this liquor, stir it, and let it get quite hot, but not boil. Just before you take it up, put in a few white mushrooms. S. Annie Frost, The Godey’s Lady’s Book Receipts and Household Hints (Philadelphia: Evans, Stoddart & Co., 1870), pp. 100-101.

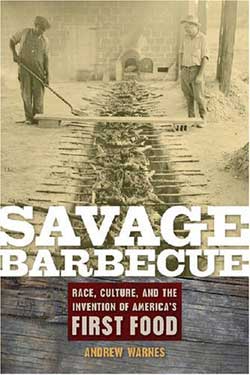

To Barbeque a Pig

Cut it open on the back, cut off the feet and clean the head as for roasting; wash it well, then dry it and sprinkle over Cayenne pepper, salt and sage. Put the inside on a gridiron and let it remain an hour, taking care to baste the skin with sweet oil, then turn it and take three fourths of a pound of butter to one pint of Port wine, melt the butter in it and baste the inside which lies uppermost, continually with it. Two hours will cook one of seven pounds’ weight. For sauce, take the inwards and boil them an hour, with a dozen cloves, a little salt and a few pepper corns, then chop them fine, add sweet herbs, a little sage if you like it, considerable white wine, some of the liquor in which it was boiled, more pepper and salt if necessary. P. H. Mendall, The New Bedford Practical Receipt Book (New Bedford: Charles Taber & Co., 1862), p. 4.

To Barbecue Any Kind of Fresh Meat

Gash the meat. Broil slowly over a solid fire. Baste constantly with a sauce composed of butter, mustard, red and black papper, vinegar. Mix these in a pan, and set it where the sauce will keep warm, not hot. Have a swab made by tying a piece of clean, soft cloth upon a stick about a foot long; dip this in the sauce and baste with it. Where a large carcass is barbecued, it is usual to dig a pit in the ground outdoors, and lay narrow bars of wood across. Very early the morning fill the pit with wood; set it burning, and in this way heat it very hot. When the wood has burned to coals, lay the meat over. Should the fire need replenishing, keep a fire outside burning, from which draw coals, and scatter evenly in the pit under the meat. Should there be any sauce left, pour it over the meat. For barbecuing a joint, a large gridiron answers well; it needs constant attention; should be cooked slowly and steadily. Mrs. A. P Hill, Mrs. Hill’s New Cook Book (New York: Carleton, 1872), pp. 139-140.

Boiled Chitterlings [Chitterlings & Gravy]

In buying the chitterlings, see that they are white and fresh. Wash them in warm water, rub in some salt, let them stand for an hour in fresh water, put them in a pot of boiling water to the fire, and let them boil, till soft. Then brown very slightly in a piece of butter, the size of a hen’s egg, three spoonfuls of flour, add a little vinegar, some lemon-peel, whole peeled onion and some nutmeg, pour off the water from the chitterlings, stir quite smooth with it the browned flour, cut the chitterlings in pieces and put them into the sauce, pour over a glass of wine, let it boil half an hour and then dish it. You may also, before dressing, add some chopped parsley and the yolks of a few eggs. . . .You may also, if you like, cut them up and bake them after they have been boiled. William Volmer, The United States Cook Book (Philadelphia: John Weick, 1859), pp. 92-93.

Hash

Now listen all ye matrons, who would save your husband’s cash,

Are you willing on a washing day to dine on savoury hash,

And save yourselves the trouble of roasting, and of boiling,

And the fear that each and every dish is in the course of spoiling:

I’ll teach how, by wise economy, you may save your scraps of meat

That are left from plenteous dinners, and make a hash complete.

Take beef that has been roasted, and rather underdone,

And from it take off all the fat, the skin, and every bone,

Then cut it up in pieces, see no cartilage remains,

Pick out each little piece of bone, and all the stringy veins,

And pound it in a mortar, or with sharp chopping knife

Mine it like meat in winter, when Christmas pies are rife.

Now boil some white potatoes, which, having mashed with care,

You must pass them through a wire sieve, to see no lumps are there,

Then mix them with your minced meat, and rub throughout the whole

Some little bits of butter, which well in flour you roll;

Or you may use the dripping that oozes from the roast.

Which every good and careful cook takes care shall not be lost.

Now season well with pepper, with salt, a little sage

And cayenne, but for this spice your taste must be the gauge,

You may chop a little onion, or chives, to give it zest,

The taste of your own family, of course you know the best;

Some much dislike an onion, or shallot, in the food,

You may leave them out with safety—’tis equally as good.

Your hash now being seasoned, you turn it in a plate,

And smooth or flour it o’er the top, and set before the grate,

Or place it in an oven, ’till handsomely ’tis browned,

And send it to the table hot—a nice dish ‘t will be found.

If any other meat you have, as mutton, veal or lamb,

‘Twill serve the purpose just as well if only minced with ham.

T., Dwights American Magazine 3, 16 (April 17, 1847), p. 244.

Hog’s head-cheese

Boil with the meat jelly half an unsalted pig’s head. When the calves’ feet are soft take them out, cover them with a cloth, so that the air may not dry up the meat, and the following day, when it is quite cold, cut it up in small dice. If there are four spoonfuls of meat, boil two spoonfuls of clarified aspic and a spoonful of very finely cut shallots, down to less than one half, mix in the meat, pour the whole, whilst still warm into a smooth deep form, in which a wet napkin has been laid, then close the napkin on top, and put it to cool. When wanted, the head-cheese is taken out of the napkin, is cut into nice-looking pieces and ornamented with aspic. When the pig’s head is too fat, it is well to put some lean boiled beef, or salt beef’s tongue with it; also fry the head-cheese before putting in into the napkin, if not sufficiently seasoned, remedy it by putting some strong vinegar, salt and pepper.

A more simple and perhaps better head-cheese, may be made in the following manner: take a pig’s head, the tongue and the ears, split the former in two, rub in a good deal of salt and some saltpetre, (to six pounds of salt take half an ounce of saltpetre,) and let it stand for three days. Then boil the head and some large pieces of fresh pig’s skin, with three bay leaves, pretty soft, in the necessary quantity of water, take it out, bone it, cut it, whilst quite hot, into dice, season it with salt and pepper, mix it well, and put it into a smooth form, which has been lined with the soft-boiled pig’s skin, and let it cool. William Volmer, The United States Cook Book (Philadelphia: John Weick, 1859), p. 100.

Preparation of Lard

The following is our mode of trying up lard, of which we make three qualities; that from the intestines, that from the leaf-fat, and that from the upper part of the back-bones. The latter is the super-fine. So soon as the intestines are taken from the hogs, while yet warm, the fat is rid off and thrown into cold water, where it remains to soak some hours; it is then washed out and put into other fresh water, in which it remains until next morning. It is then cut up into pieces not more than two or three inches long, rinsed again and immediately put on in iron boilers thoroughly cleansed. The fire is then applied, which must be free from smoke during the whole process of boiling, which should be continued for at least twelve hours. It is very frequently stirred during the boiling, and the bottom of the boiler scraped hard with the sharp edge of the iron ladle, to keep the cracklings from adhering and burning, which they are apt to do towards the end of the process if the fire is strong and the boiling rapid. When the cracklings begin to turn brown, and the lard becomes clear as water and scarcely any evaporation is visible, the fire should be slackened. The bubbles rising to the top will be as clear as cut glass. Continue the simmering gently until the cracklings are quite brown. They never become crisped; but although brown and entirely done, will be soft and flabby. The clearness of the lard, the brown color of the cracklings, the crystal purity of the bubbles, and the nut-like scent arising, indicate the end of the boiling. Take the boilers off the fire, or extinguish the fire, and when the lard is so cool that you can bear its heat on your finger dipped into it without pain, strain it off into clean tight vessels. Exclude the air; and you will have a nice article even from gut fat. John Lewis, Llangollen KY Southern Planter 1, 11 (December 1841), 238.

Mutton

Mutton is in its greatest perfection from August to Christmas. For roasting or boiling allow fifteen minutes for each pound. The saddle should always be roasted, and garnished with scraped horse radish. The leg and shoulder are good roasted; but the best way of cooking the leg is to boil it with a bit of salt pork. If a little rice is boiled with it the flesh will look whiter.

For roasting, mutton should have a little butter rubbed over it, and salt and pepper sprinkled on it. Allspice and cloves, some like. Put a piece of butter in the dripping pan, and baste it often. The bony part should first be presented to the fire, for roasting.

The leg is good to bake, gashed and filled with a dressing made of soaked bread, pepper, salt, butter, and two eggs. A pint of water, and a little butter should be put in the pan.

The leg is good, too, sliced and broiled. Also boiled, after corned a few days.

The rack is good for broiling. Each bone should be separated, broiled quick, buttered, salted, and peppered.

The breast is fine baked. The joints of the brisket should be separated; the sharp ends of the ribs sawed off; the outside rubbed over with a small piece of butter; salted; and put into a bake pan, with half a pint of water. When baked enough, take it up, and thicken the gravy with a little flour and water, adding a small piece of butter. A spoonful of catsup, cloves and allspice, improve it. The neck makes a good soup. Mrs. A. L. Webster, The Improved Housewife, or Book of Receipts (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, and Co., 1853), p. 41.

Mutton Hams

Mix two ounces of brown sugar with an ounce of fine bay salt and half a table spoonful of salt petre; rub the ham therewith, and lay it in a deep dish; baste and turn it twice a day for three days; throw away the pick which in this time will have drained from the ham, and wipe it dry. Rub it again with the same mixture of sugar, etc., one day, and baste it the next, for ten days, turning it every day. Smoke for ten days, (with green hickory, if possible.) The hams are best eaten cold. New England Farmer 3, 28 (April 15, 1825), 299.

To make Scrapple

Take the heart, kidneys, sweet-bread, milt and liver, and put them to boil. The liver will be done sufficiently in an hour. Chop all very fine, take the skins and scraps unfit for sausages, the feet and tongue, boil them all very tender, chop them fine and return them to the liquor they were boiled in, salt, pepper and sage must be added according to the taste; when boiling, stir in buckwheat meal to the thickness of mush, keep it stirring while it boils to prevent it from burning; it need not boil long. P. H. Mendall, The New Bedford Practical Receipt Book (New Bedford: Charles Taber & Co., 1862), p. 10.

Possum

As an article of food the opossum is considered by many a very great luxury, the flesh, it is said, tastes not unlike roast pig. In cooking the ‘varmint,’ the Indians suspend it on a stick by its tail, and in this position they let it roast before the fire; this mode does not destroy a sort of oiliness, which makes it to a cultivated taste coarse and unpalatable. The negroes, on the contrary—and, by the way, they are all amateurs in the cooking art—when cooking for themselves do much better. They bury the body up with sweet potatoes, and as the meat roasts thus confined, the succulent vegetable draws out all objectionable tastes, and renders the opossum ‘one of the greatest delicacies in the world.’ T. B. T. Louisiana, October 1841, Spirit of the Times 11, 40 (December 4, 1841), 469.

Fricassee of Squirrels

Put two young squirrels into a pot with two ounces of butter, one or two ounces of ham, some salt and pepper, and just water enough to cover them. Let them stew slowly until tender. Take them up, and pour half a teacup of cream and beaten yolk of egg into the gravy, and when it has boiled five minutes, pour over the squirrels in the dish. Some persons prefer a wineglass of red wine, and omit the cream and egg. Mrs. Barringer, Dixie Cookery: or How I Managed my Table for twelve years (Boston: Floring, 1867), p. 26.

To Roast Venison

The best joints to roast are the haunch and the loins, which last should be cut saddle fashion, viz, both loins together. If the deer be fat and in good season, the meat will need no other basting than the fat which runs from it; but as it is often lean, it will be necessary to use lard, butter, or slices of fat bacon to assist the roasting. Venison should be cooked with a brisk fire—basted often—and a little salt thrown over it; it is better not overdone. Being a meat very open in the grain and tender, it readily bastes with its juices, and takes less time to roast than any other meat. Mrs. C. P. Traill, The Canadian Settler’s Guide (Toronto: Toronto Times, 1857), p. 152.

Brown Fricassee of Venison

Fry your steaks quite brown, in hot dripping; put them in a stewpan with a very little water, a bunch of sweet herbs, a small onion, a clove or two, and pepper and salt. When it has boiled for a few minutes, roll a bit of butter in flour, with a table-spoonful of catsup or tomato-sauce, and a tea-spoonful of vinegar; stir this into the fricassee, and dish it quite hot. Mrs. C. P. Traill, The Canadian Settler’s Guide (Toronto: Toronto Times, 1857), p. 152

Sauces

Chestnut Sauce for Roast Turkey

Scald a pound of ripe chestnuts, peel them, and stew them slowly about two hours in white gravy; then thicken with butter and flour, and serve the sauce poured over the turkey. Pork sausages, cut up and fried, are sometimes put into this sauce. Sarah Josepha Hale, Mrs. Hale’s New Book of Cookery (New York: H. Long & Brother, 1852), p. 201.

Indiana Sauce

One ounce of scraped horseradish, one ounce of mustard, one of salt, half an ounce of celery seed, two minced onions, and half ounce of cayenne, add a pint of vinegar; let it stand in a jar a week, then pass it through a sieve, and bottle it up securely. Mrs. A. M. Collins, The Great Western Cook Book (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1857), p. 32.

Lobster Sauce

Take out all the meat and soft part from the body; cut it up very fine, and put it into a sauce-pan with a pint and a half of white stock. Braid into a quarter of a pound of butter a large spoonful of flour; stir it in, and add a little salt, pepper, and vinegar; give it one boil. Send it to the table, in an oyster-dish, as sauce for boiled fish. Dollar Monthly 20, 3 (September 1864), 240.

Pepper Catsup

Fifty pods of large red peppers, with the seeds. Add a pint of vinegar, and boil until the pulp will mash through a sieve. Add to the pulp a second pint of vinegar, two spoonfuls of sugar, cloves, mace, spice, onions, and salt. Put all in a kettle and boil to a proper consistency. S. Annie Frost, The Godey’s Lady’s Book Receipts and Household Hints (Philadelphia: Evans, Stoddart & Co., 1870), p. 78.

Tomato Catsup

Take two quarts of skinned tomatoes, two tablespoonfuls of black pepper, and one of allspice, a little Cayenne, two tablespoonfuls of ground mustard; mix and rub these thoroughly, and stew them slowly in a pint of vinegar, for three hours; then strain the liquor through a sieve, and simmer it down to one quart of catsup. Put this in bottles, and cork it tight. Mrs. J. Chadwick, Mrs. Chadwick’s Cook Book. Home Cookery: a Collection of Tried Receipts (Boston: Crosby, Nichols, & Co., 1853), p. 100.

Vegetables

Baked Beans

Put a quart of white beans to soak in soft water, at night; the next morning wash them out of that water; put them into a pot with more water than will cover them; set them over the fire to simmer until they are quite tender; wash them out again and put them into an earthen pot, scald and gash one and a half pounds of pork, place it on top of the beans and into them, so as to have the rind of the pork even with the beans; fill the put with water, in which is mixed two table-spoonsful of molasses. Bake them five or six hours; if baked in a brick oven it is well to have them stand over night. Mrs. Putnam’s Receipt Book (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1850), p. 64.

Pickled Beets

Parboil some of the finest red beet roots in water; then cut them into a sauce-pan with some sliced horse-radish, onions, shallots leaves, pounded ginger, beaten mace, white pepper, cloves, all-spice, and salt; and boil the whole in sufficient vinegar to cover it for at least a quarter of an hour. Strain the liquor from the ingredients, put the slices into a jar, pour the strained liquor over them, and if higher colour be wanted, add a little powdered cochineal when the pickled is quite cold, and keep it closely covered with bladder or leather. A little oil may be poured on the top of this pickle which will assist the better to preserve it without prejudice to the beet root, which is common served up in oil, its own liquor, and small quantity of powdered loaf sugar poured over it. Some also add mustard, but this is by no means necessary, and certainly does not improve the colour of this fine pickle. New England Farmer III, 9 (Sept. 25, 1824), p. 67.

Broccoli and Buttered Eggs

Keep a handsome bunch for the middle, and have eight pieces to go round; toast a piece of bread to fit the inner part of a dish or plate; boil the broccoli. In the mean time have ready six (or more) eggs beaten, put for six a quarter of a pound of fine butter into a saucepan, with a little salt, stir it over the fire, and as it becomes warm add the eggs, and shake the saucepan till the mixture is thick enough; pour it on the hot toast, and lay the broccoli as before directed. This receipt is a very good one, it is occasionally varied, but without improvement, the dish is however nearly obsolete. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Ellet, The Practical Housekeeper (New York: Stinger & Townsend, 1857), p. 388.

Brussels Sprouts

This delicate vegetable can be cooked in several ways; but the following method, communicated to the author by a gentleman many years resident in Brussels, will be found to produce, as old Gerrard used to say, ‘a dainty dish.’ After the sprouts have been frosted, a process which renders them more tender and sweet, they may be gathered; (the more close and compact they are the better.) Immerse them in clear soft water for an hour or two, to cleanse them from any dirt or insects; then boil them for about twenty minutes rather quickly, using plenty of water; when soft they must be taken up and well drained; they are then to be put into a stew-pan, with cream, or with a little fresh butter thickened with flour, and seasoned with pepper and salt, and stirred until they are thoroughly hot. They are served up to table with a little tomato vinegar, which greatly heightens their flavour. Southern Agriculturist, Horticulturist, and Register of Rural Affairs 3 (March 1841), 144.

Cabbages

There are more ways to cook a fine cabbage than to boil it with a bacon side, and yet few seem to comprehend, that there can be any loss in cooking it, even in this simple way. Two-thirds of the cooks place cabbage in cold water, and start it to boiling, this extracts all the best juices, and makes the pot liquor a soup. The cabbage head, after having been washed and quartered, should be dropped into boiling water, with no more meat than will just season it. Cabbage may be cooked to equal broccoli or cauliflower. Take a firm sweet head, cut it into shreds, lay it in salt and water for six hours. Now place it in boiling water, until it becomes tender—turn the water off, and add sweet milk when thoroughly done, take up a colander and drain. Now season with butter and pepper, with a glass of good wine and a little nutmeg grated over, and you have a dish little resembling what are generally called greens. Southern Planter 14, 9 (September, 1854), 271.

Saur Kraut

Take as many drum-head cabbages, or any other kind having a firm head, as you wish to preserve, tear off the outer leaves, quarter them, cut out the stalks, and chop the remainder into small pieces by hand or with a machine. Then, to every one hundred pounds of cabbage take three pounds of salt, one-quarter pound of caraway seed, and two ounces of juniper berries, and mix them together in a dish or bowl. Then procure as many clean casks, strongly hooped with iron, as may be required, and fill them with layers of chopped cabbage, about three inches thick, sprinkling each layer, as it is pressed in, with the mixture of caraway seed, juniper berries and salt. When each cask is full, lay over it a coarse linen cloth and a wooden follower or lid, just fitting within the mouth of the cask, upon which must be placed a stone or weight sufficiently heavy to prevent it from rising, and allow it to ferment for a month. The cabbage produces a great deal of water, which floats around the sides of the casks to the top of the follower or lid. This must be poured off, and its place supplied with a solution of lukewarm warm water, whole black pepper and common salt, taking care that the cabbage is always covered with brine. In order to keep the kraut fresh and for a long time, the casks should be placed in a cool situation as soon as a sour smell is perceived. Southern Planter 8, 3 (March 1848), 88.

A Carrot Pudding

You must take a raw carrot, scrape it very clean, and grate it; take half a pound of the grated carrot, and a pound of grated bread; beat up eight eggs, leave out half the whites, and mix the eggs with half a pint of cream; then stir in the bread and carrot, half a pound of fresh butter melted, half a pink of sack, three spoonfuls of orange flower water, and a nutmeg grated. Sweeten to your palate. Mix all well together; and if it is not thin enough stir in a little new milk or cream. Let it be of a moderate thickness: lay a puff-paste all over the dish, and pour in the ingredients. Bake it, which will take an hour. It may also be boiled. If so, serve it up with melted butter, white wine, and sugar. Susannah Carter, The Frugal Housewife, or Complete Woman Cook (New-York, C & R Waite, 1803), pp. 166-67.

Fried Cauliflower

Having laid a fine cauliflower in cold water for an hour, put it into a pot of boiling water that has been slightly salted, (milk and water will be still better,) and boil it twenty-five minutes, or till the largest stalk is perfectly tender. Then divide it equally, into small tufts, and spread it on a dish to cool. Prepare a sufficient quantity of batter made in the proportion of a table-spoonful of flour, and two table-spoonfuls of milk to each egg. Beat the eggs very light; then stir into them the flour and milk alternately; a spoonful of flour, and two spoonfuls of milk at a time. When the cauliflower is cold, have ready some fresh butter in a fry-pan over a clear fire. When it has come to a boil and has done bubbling, dip each tuft of cauliflower twice into the pan of batter, and fry them a light brown. Send them to table hot. Miss Leslie, The Lady’s Receipt-Book (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1847), p. 40.

Indian Corn or Roasting Ears

Who don’t know how to cook roasting ears? But if every body does know how to cook them, it is seldom we find green corn upon the table, with all its good qualities preserved. It is no wonder that our negroes are so greedy for pot liquor, when in nine cases out of ten, it contains all the best of the vegetables. Corn boiled in the ear should be dropped into boiling water with salt to season. Corn cut from the ear, and boiled in milk seasoned with butter, pepper and salt, is an excellent dish. Corn cut from the cob after boiling, and mixed with butter beans, seasoned with butter, pepper and salt, makes succotash, a capital dish. Corn oysters is a delicious dish: grate the green corn from the cob, season with salt and pepper, mix in batter, and fry in butter. Green corn pudding is a great delicacy: grate the corn from the cob, mix sweet milk and flour until of the consistency of paste, season with anything the taste may dictate, and bake in a hot oven—it should bake quick. Southern Planter 14, 9 (September, 1854), 271.

A Crookneck or Winter Squash Pudding

Core, boil and skin a good squash, and bruise it well; take 6 large apples, pared, cored, and stewed tender, mix together; add 6 or 7 spoonsful of dry bread or biscuit, rendered fine as meal, half pink milk or cream, 2 spoons of rose-water, 2 do. Wine, 5 or 6 eggs beaten and strained, nutmeg, salt and sugar to your taste, one spoon flour, beat all smartly together, bake. Lucy Emerson, The New-England Cookery (Montpelier: Josiah Parks, 1808), p. 49.

To Stew Cucumbers

Peel and cut cucumbers in quarters, take out the seeds, and lay them on a cloth to drain off the water; when they are dry, flour and fry them in fresh butter; let the butter be quite hot before you put in the cucumbers; fry them till they are brown, then take them out with egg-slice, and lay them on a sieve to drain the fat from them (some cooks fry sliced onions, or some small botton onions, with them, till they are a delicate light brown color, drain them from the fat, and then put them into a stewpan with as much gravy as will cover them); stew slowly till they are tender; take out the cucumbers with a slice, thicken the gravy with flour and butter, give it a boil up, season it with pepper and salt, and put in the cucumber, as soon as they are warm, they are ready. The above, rubbed through a tamis, or fine sieve, will be entitled to be called “cucumber sauce.” This is a very favorite sauce with lamb or mutton cutlets, stewed rump-steaks, &c., when made for the latter, a third part of sliced onion is sometimes fried with the cucumber. A Boston Housekeeper, The Cook’s Own Book, and Housekeeper’s Register (Boston: Munroe & Francis, 1840), p. 60.

Dandelion

Pick and wash your dandelion and cut off the roots. Drain it, and make a dressing of an egg, well beaten, a half a gill of vinegar, a tea spoonful of butter, and salt to the taste. Mix the egg, vinegar, butter and salt together, put the mixture over the fire, and as soon as it is thick, take it off, and stand it away to get cold. Drain your dandelion, pour the dressing over it and send it to the table. Lady of Philadelphia, The National Cook Book (Philadelphia: Hayes & Zell, 1856), p. 94.

Egg Plant

The purple is better than the white; they must be boiled in plenty of water until tender, then take up, and take off the skins, and drain; cut them up and wash in a deep dish or pan; mix some grated bread, powdered sweet marjoram, a piece of butter, and a few pounded cloves; grate a layer of bread over the top, and brown in the oven; send to the table in the same dish. It is generally eaten at breakfast. Mrs. Laura Trowbridge, Excelsior Cook Book and Housekeeper’s Aid (New York: Mason, Baker & Pratt, 1870), p. 87.

Broiled Egg Plant

Split the egg plant in two, peel it, and take the seeds out, put it in a crockery dish, sprinkle on chopped parsley, salt, and pepper; cover the dish, and leave thus about forty minutes; then take it off, put it on a greased and warmed gridiron, and on a good fire; baste with a little sweet oil, and seasoning from the crockery dish, and serve with the drippings when properly broiled. It is a delicious dish. Pierre Blot, What to Eat, and How to Cook It (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1863), p. 182.

Mustard

There are two species of this plant, the white and the brown seeded or black mustard. The white is used as a salad. It is the black mustard which bears the seed used in commerce and from which the condiment is obtained.

In the manufacture of mustard some white seed combined with the black is said to make the best. They are ground in a mill and sifted to a fine flour. One of the grand secrets of making it good, is to keep it perfectly dry from the seed to the time of use. The pungency of mustard, the quality by which it raises blisters on the skin and bites the tongue is owing to a volatile oil which is not originally present in the dry flour. It is created by the chemical action of two substances which compose it (known to the chemists as emulein and myronic acid.) These do not act upon one another until water is added.—When the flour is moistened they quickly form the oil. Vinegar diminishes this changes. It is, therefore, a great mistake to use it in preparing mustard. Tepid water is the proper fluid both to mix up the condiment and to make the irritating poultice. As we have before said, the oil is of a valuable character and will after awhile fly away and leave the mustard without strength. It should then be prepared but a few hours before the time when wanted for use. Southern Planter 8, 1 (January 1848), 27.

Stewed Onions

Young onions should always be cooked in this way: Top, tail, and skin them; lay them in cold water half an hour or more, then put into a saucepan with hot water enough to cover them; when half done, throw off all the water except a small teacupful—less, if your mess is small; add a like quantity of milk, a large spoonful of butter, with pepper and salt to taste; stew gently until tender, and turn into a deep dish. If the onions are strong and large, boil in three waters, throwing away all of the first and second, and reserving a very little of the third to mix with the milk. Mrs. Washington, The Unrivalled Cook-Book and Housekeeper’s Guide (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1886), p. 199.

Parsnip Fritters