Salem Witchcraft in the Classroom

With bewitching results

Like many other professors, I have often offered seminars on subjects related to my current research interests. Teaching a topic to either undergraduate or graduate students forces me to review the secondary literature thoroughly and to clarify interpretive themes and identify promising historical questions. Thus, some years ago, when I first began to consider writing a book on the Salem witchcraft crisis of 1692, I started occasionally teaching advanced (four-hundred-level) seminars—courses required of all our history majors—on the subject of “Witchcraft in Early Modern England and America.”

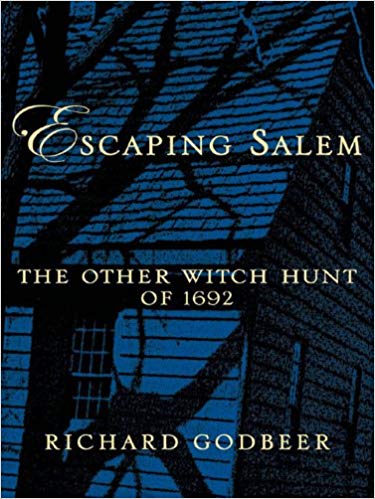

After the 2002 publication of In the Devil’s Snare, my book on the events of 1692, I at first thought with regret that I could no longer offer witchcraft seminars because I now knew the answers to the questions that had puzzled me for so long. But then I realized that my research had revealed many yet-unexamined aspects of the Salem crisis and that, if I could point students specifically in the direction of those subjects, I could still offer a course that I found intellectually stimulating. A two-hundred-level seminar—aimed primarily at introducing prospective history majors to primary-source research by requiring them to write ten- to fifteen-page term papers along with other shorter essays—seemed to me the ideal vehicle for pursuing this goal.

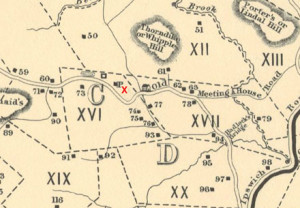

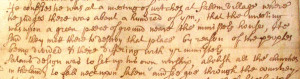

And so, in the fall of 2003 I offered such a lower-level seminar on Salem witchcraft. Sixteen students enrolled, representing every class from freshmen to seniors and including a mature woman in Cornell’s employee degree program. After having the students read several general works on witchcraft in Europe and America, I focused the course exclusively on Essex County in 1692 and assigned both Bernard Rosenthal’s Salem Story and my own book. Throughout the semester the students and I referred frequently to the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive, a Website run by Ben Ray of the University of Virginia, which includes images of the surviving original documents and keyword-searchable transcriptions from Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum’s three-volume edition of The Salem Witchcraft Papers (1977), along with literary and visual representations of the crisis and other source material. I used the Website both to teach the students how to read seventeenth-century handwriting and to show them the importance of comparing the sometimes flawed published transcriptions with original documents.

The course turned out remarkably well, as the students developed their own topics under my guidance. With the support of Ben Ray, I held out the prospect of “publication” on his Website for the best papers, and that proved to be a strong incentive for several of the students. In the end, four papers stood out as making truly original contributions to scholarship on Salem witchcraft. Two students wrote biographies of executed women who had attracted scant attention from earlier scholars: Jacqueline Kelly researched Mary Parker of Andover in an innovative way, and Mark Rice uncovered the background to the accusation of Margaret Scott of Rowley. The other two students examined hitherto overlooked groups of accused people: Darya Mattes analyzed the very youngest accused children, and Jedediah Drolet studied accused women from Gloucester. At the time they enrolled in the class, Darya was a junior (a dual major in history and anthropology), and the other three were freshmen, two of whom have since chosen to major in history.

Fortuitously the completion of the course coincided with a gift to the department by Cornell parents Nick and Judy Bunzl, who sought to encourage professors to work with undergraduates to present their research at professional meetings. I asked the four students if they were interested in continuing to pursue their projects, and all readily agreed. Knowing that the Thirteenth Berkshire Conference on Women’s History was scheduled for June 2005 at Scripps College in Claremont, California, and that the “Big Berks,” as it is familiarly known, had a long tradition of openness to young scholars, I proposed to the program committee a first-ever undergraduate panel. After some discussion, they accepted the proposal.

Over the intervening year and a half, the students continued to refine their papers, occasionally consulting me in the process. Two made summer trips to do additional research, financed by the Bunzel’s generous gift—one to Salem, one to Gloucester. In the months before the conference, we held two rehearsals at which I listened to and critiqued the revised papers as they were read aloud. The big day came on Sunday, June 5, 2005, at 8:30 in the morning. Given the timing, the audience was small (ten or twelve people), but it was nevertheless knowledgeable and enthusiastic. The students performed beautifully, presenting their papers well and answering questions with great assurance. Elizabeth Reis of the University of Oregon, the commentator, warmly complimented their work. They also attended additional conference sessions, again thanks to the Bunzel’s gift, and they greatly impressed other conferees, several of whom sought me out to tell me of encounters with them. In short, I was thrilled by the results.

In the sciences, more and more emphasis is being placed on integrating undergraduates into research groups early in their college careers. My experience with this group of Cornell students has convinced me that historians should follow the scientists’ example within our disciplinary context. In all likelihood, because of the success of this experiment, the next Big Berks will include a specific call for undergraduate panel proposals; regional historical gatherings might also be amenable to them. Accordingly, I encourage other professors to contemplate the possibility of engaging undergraduates in similar projects. This has been among my most rewarding experiences as a teacher of undergraduates.

The four students’ papers together add new dimensions to historians’ knowledge of the 1692 crisis. Scholarship on the crisis has traditionally focused on Salem Village (now Danvers), where the witch hunt originated. Residents of the village have been investigated in detail, most notably by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, in Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft (Cambridge, Mass., 1974), but few historians other than Carol Karlsen (in The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England [New York, 1987]) have paid much attention to any accused witches from elsewhere in Essex County. Almost all of Darya Mattes’s accused children and Jackie Kelly’s subject, Mary Ayer Parker, lived in Andover, a town that produced more accused witches than Salem Village. Even so, the witch hunt in Andover has been the subject of only one scholarly article and an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Therefore, my students are among just a handful of researchers who have seriously examined the behavior of people from that town in 1692. Likewise, Jedediah Drolet’s study of the accused witches of Gloucester broke new ground by exposing the close familial ties between women with differing surnames who bore no immediately obvious relationship to each other. Finally, Mark Rice carefully reconstructed the life of Margaret Scott of Rowley. Because the testimony and other documents in her case became separated from the bulk of the surviving legal records, they were not printed in Boyer and Nissenbaum’s Salem Witchcraft Papers, and thus few scholars have paid any attention to her.

Brief versions of the papers follow, with links to full texts of the revised papers (essentially as presented at the Berkshire Conference) on the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive Website.

Darya Mattes developed her topic independently, with little input or guidance from me. Her focus on the accusations of very young children and their confessions highlighted the importance of family ties in the Salem crisis and exposed some fundamental Puritan assumptions about the nature of childhood.

Darya Mattes, “Accused Children in the Salem Witchcraft Crisis”

The witchcraft crisis in Essex County, Massachusetts, in 1692 has long been known for its unusual list of accused witches; however, one atypical group of accused has been largely overlooked in the literature on Salem. Over the course of the crisis, at least eight children under the age of twelve were accused of witchcraft, and most were indicted. Certain commonalities exist in all of the children’s cases: the evidence offered against the children dealt with spectral sightings rather than personal harm, all of the children confessed to being witches, and each of the eight children had an accused witch for a mother. A study of these unusual cases, in conjunction with an examination of the ways in which Puritan individuals were situated within the family and the religious sphere, can thus offer insights into the infamous events of 1692.

A brief description of each case serves to highlight their recurring themes and possible implications. Two of the best-documented cases of accused children were those of Sarah Carrier and Thomas Carrier Jr. of Andover, aged seven and ten respectively. The Carrier children’s case offers a clear example of witchcraft accusations as linked to family ties: their mother and two older brothers were accused and convicted witches as well. Sarah and Thomas Carrier reinforced this connection in their confessions, directly implicating their mother in their own “witchcraft.” The case of Margaret Toothaker, a third child witch who was ten in 1692, exemplifies this emphasis on family connections in a different way. Not only were both of Margaret’s parents accused witches, but Margaret’s name never appears in the court records; she was referred to repeatedly as the daughter of her father or her mother, or even as a cousin, but never as an individual. Abigail Johnson was eleven years old when she was accused and, like the others, had family members—in her case, her mother and older sister—who were accused as well. Additionally, she was accused by prominent “afflicted girls,” a situation that is representative of many of the children’s cases. Three more accused children, Abigail Faulkner Jr, Dorothy Faulkner, and Johanna Tyler, were eight, ten, and eleven when accused, and all had accused-witch mothers. Whereas these seven children all came from Andover—Margaret Toothaker had moved to Billerica from Andover before the trials, while the others still lived there—the last accused child, Dorothy Good, was from Salem Village. Dorothy was only four or five at the time of the trials, and she was accused several months before the other children. However, she too was accused by “afflicted girls,” confessed to witchcraft, and implicated her mother, who was also an accused witch.

Significantly, the notion of a child as a witch did not contradict Puritan belief. Because the focus in Salem was on spectral torment, a witch in 1692 was primarily defined as one who had made a covenant with the devil and who worked with him to afflict other individuals. Because the devil worked through people in this way, even a very young, inexperienced person could, for a Puritan, conceivably be a witch. Puritan adults also viewed the children as religiously precocious. Puritan communities were deeply and pervasively religious, and adults often read religious meaning into their children’s actions, perhaps even beyond children’s actual comprehension. Compounded with the little theological knowledge that Puritans expected in a believable witch, this fact meant that the notion of children as witches was not at all incongruous in Puritan belief.

In fact, the religious climate in Salem in 1692 may have made children more likely than adults to believe that they were actually witches. With its rhetoric of original sin and eternal damnation, Puritan doctrine may have worked with childhood fears to convince children of their own inherent immorality and unworthiness. They would have been likely, therefore, to confess to crimes that were already credible according to Puritan beliefs about both witchcraft and childhood.

The institution of the family was integral in Puritan society as well, occupying a central role in personal identity and spiritual well-being. Individuals, particularly women and children, were consistently referred to through their linkages to others, as “wife of,” “daughter of,” or “son of.” Interestingly, the children accused of witchcraft were most often referred to as the daughters of their mothers. Because mothers, in Puritan society, were charged with setting a spiritual example for their families, having an accused witch for a mother almost necessarily implied that a child would have been tainted as well. Indeed, because Puritan religion was learned within the family, the “inheritance” of witchcraft from mother to child was an inversion of Puritan doctrine, in which adherents followed the devil instead of God but in which the primary means of initiation was the same.

Witchcraft accusations of young children at Salem thus serve to highlight the strength and focus of Puritan belief, particularly exemplifying Puritan notions of witchcraft, religion, and family relations. These ideas, in turn, can help illuminate not only the cases of children but the crisis as a whole.

Jedediah Drolet followed up my suggestion that students look at clusters of accusations in towns that had attracted little scholarly attention. His meticulous examination of the genealogical links among the little-known accused witches of Gloucester—based in part on summer research conducted in Gloucester’s manuscript town records after the seminar had ended—demonstrated that even women from substantial families could be the objects of suspicion.

Jedediah Drolet, “The Geography and Genealogy of Gloucester Witchcraft”

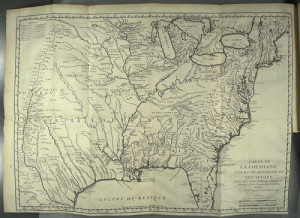

Other towns in Essex County besides Salem experienced witchcraft allegations in 1692. One of these towns was Gloucester, which produced more witchcraft accusations than any other town except Andover, Salem Village, and Salem Town. This paper puts forth a new explanation for this phenomenon: conflicts among the town’s elites during a period of high social stress throughout the colony.

The Gloucester residents accused of witchcraft in 1692 fall neatly into a few discrete groups. This paper will focus on two groups, which were closely connected. Phoebe Day, Mary Rowe, and Rachel Vinson were accused sometime in the fall of 1692. There is no record of their accusation or examination extant, but their names were on a petition to the governor and council signed by a group of prisoners held at Ipswich jail. A warrant for the arrest of another group of women, Esther Elwell, Abigail Rowe, and Rebecca Dike, was issued on November 3, 1692, for afflicting Mrs. Mary Fitch. This paper will focus on these women, their accusers, and the possible connections between them and the first group of three.

When Mary Fitch became ill in the fall of 1692, Lieutenant James Stevens sent for the “afflicted girls” of Salem Village to find out who had bewitched her. The girls named Rebecca Dike, Esther Elwell, and Abigail Rowe as the witches, and Stevens subsequently filed a complaint with the magistrates. A warrant for the three was issued November 5. James Stevens, the complainant, was an important figure in town, a deacon of the church, and a lieutenant in the militia. He married Susannah Eveleth, daughter of Sylvester Eveleth, in 1656. At his death in 1697 his estate totaled £239 19s.

Esther Dutch was born around 1639 and married Samuel Elwell in 1658. At the death of Samuel’s father, Robert Elwell, the value of his estate totaled £290 10s. Rebecca Dolliver married Richard Dike in 1667. They lived at Little River. Over the years Richard’s landholdings there steadily grew through grants from the town and purchases from neighbors such as Joseph Eveleth, the son of Sylvester Eveleth and brother of James Stevens’s wife Susannah.

Abigail Rowe was born in 1677 to Hugh and Mary Prince Rowe. The fact that she was only fifteen years old in 1692 shows the peculiarity of her case. While it was certainly not unheard of for children to be accused of witchcraft, they were generally accused along with other family members. Seeing a teenaged girl accused along with two adult women is quite unusual, but she was not the only woman in her family accused of witchcraft. Her mother was one of the three women listed in the petition from Ipswich jail, and her grandmother was Margaret Prince, accused early on and also listed in the Ipswich petition. The apparent link between the Ipswich prison group and the November accusations becomes stronger because of the connections between the Rowe family and the Day and Vinson families.

Hugh Rowe and his older brother John received equal portions of their father John’s estate of £205 16s. 10d. Five years later, Hugh and John entered into an agreement witnessed by Robert Elwell, who owned land near theirs. In 1685, Hugh Rowe received three parcels of land from his “father-in-law” William Vinson, likely the father of his first wife, Rachel Langton. Hugh and Rachel Rowe’s daughters married sons of Anthony Day. Another of Anthony Day’s sons, Timothy, married Phoebe Wilds, one of the women mentioned in the Ipswich petition.

Thus Hugh and Mary Rowe lived near Robert Elwell and had a close relationship to William Vinson and the Day family. Mary was also the daughter of Margaret Prince. All of the Gloucester women whose accusations are known only from the Ipswich petition were connected to the Rowe family. This provides clear evidence that there was a connection between their accusations and the accusation against Esther Elwell, Rebecca Dike, and Abigail Rowe. The likely cause of the accusations was animosity between different members of the town elite, which spiraled out of control in the context of the witchcraft panic and other tensions facing Massachusetts at the time.

These accusations all involved people of high social and economic status. The Gloucester accusations involved no singling out of poor, marginal women. All of the recorded estates of these families were valued at more than two hundred pounds. They all had comparatively large holdings of land and held many town offices. The cases seem to have been based on fear and suspicion among the upper class against a backdrop of paranoia throughout the county.

To my knowledge, Jacqueline Kelly is the only person who has ever seriously investigated Mary Ayer Parker’s statement in her own defense that she had been arrested erroneously, mistaken for another woman of the same name. And, remarkably, Jackie found that Goody Parker’s defense was most likely true. To me, her findings offered an important insight into the disarray of the legal process during the last set of trials, in September 1692.

Jacqueline Kelly, “The Untold Story of Mary Ayer Parker: Gossip and Confusion in 1692”

Mary Ayer Parker was tried and convicted of witchcraft in September 1692 by the Court of Oyer and Terminer in Salem, Massachusetts. In less than one month, she was arrested, examined, found guilty, and executed. Historians have paid little attention to her case, one in which it is nevertheless possible to discern where confusion and conspiracy could have arisen, leading to her untimely death.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of Mary’s examination was her forceful claim to her examiner: “I know nothing of it [witchcraft] . . . There is another woman of the same name in Andover.” Her denial was quickly dismissed, but she did not lie. In fact, there were not one but three other Mary Parkers in Andover. One was Mary Ayer’s sister-in-law, Mary Stevens Parker, wife of Mary Ayer’s husband Nathan’s brother Joseph. The second was Joseph and Mary’s daughter Mary. The third was the wife of Mary and Joseph’s son, Stephen. To complicate things further, there was a fourth Mary Parker living nearby in Salem Town.

By asserting she was not the Mary Parker the court sought, Mary insinuated that another woman was a more probable culprit. And, true enough, the reputations of two of these Mary Parkers could indeed have sullied the namesake. Mary Ayer Parker’s sister-in-law had a documented history of mental instability. Essex County Court records from the period showed that both Joseph’s wife and his son Thomas were perceived to be mentally unstable or ill. At the time, insanity was sometimes associated with other deviant behavior, including witchcraft. Rebecca Fox Jacobs, long regarded a lunatic in Essex County, confessed to witchcraft in 1692. Her mother Rebecca Fox petitioned both the Court and Massachusetts’s Governor Phips for her release on the grounds of her mental illness.

The reputation of “Mary Parker” was further tarnished by the lengthy criminal history of Mary Parker from Salem Town. Throughout the 1670s, Mary appeared in Essex County Court a number of times for fornication offenses, child support charges, and extended indenture for having a child out of wedlock. She was a scandalous figure and undoubtedly contributed greatly to negative associations with the name Mary Parker.

A disreputable name could have been enough to kill the wrong woman in 1692. In a society where the literate were the minority, the spoken word was the most damaging. Gossip, passed from household to household and from town to town through the ears and mouths of women, was the most prevalent source of information. The damaged reputation of one woman could be confused with another as tales of “Goody so-and-so” filtered through the community. For example, Susannah Sheldon, one of the so-called afflicted girls that led many of the witchcraft accusations in1692, mistakenly attributed gossip about Sarah Bishop to Bridget Bishop when she accused her. The confusion associated with their cases proved how the bad reputations garnered by Mary Parker the fornicator from Salem and the mentally ill Mary Stevens Parker of Andover could have significantly affected the vulnerability of Mary Ayer Parker.

William Barker Jr., who testified against Mary Ayer Parker, may have been confused as well. In his own confession, William accused a “goode Parker,” but he did not specify which Goody Parker he meant. There was a good possibility that William Barker Jr. heard gossip about one Goody Parker or another, and the magistrates of the court took it upon themselves to issue a warrant for the arrest of Mary Ayer Parker without making sure they had the right woman in custody.

The other suspicious side of the proceedings involved the women who testified against Mary Ayer. Hannah Bigsbee and Sarah Phelps were both members of the prominent Chandler family of Andover. Captain Thomas Chandler, who signed the indictment, was father and grandfather to the women respectively. There was virtually no evidence of any previous strife between the Parker and Chandler families. Nathan, Mary Ayer’s husband, and his brother Joseph settled in Andover at the same time as the Chandlers. Nathan, Joseph, and Thomas served public offices together and maintained property adjoining each other’s. Joseph Parker’s will referred to Thomas as his “dear friend.” However, the relationship between the families, at least Nathan’s branch, must have soured sometime after the 1680s, when both Parker brothers had died. The powerful and influential Chandler family gave credibility to the case against Mary Ayer Parker, and they indeed knew which Mary Parker she was. While clear evidence of a rift is not extant, the bad blood is evident.

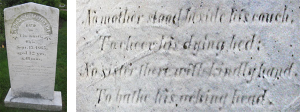

Mary Ayer Parker was convicted on little evidence, and even that seems tainted and misconstrued. The Salem trials did her no justice, and her treatment was indicative of the chaos and ineffectualness that had overtaken the Salem trials by the fall of 1692. Salem historians, who have studied her little and written misinformed accounts of her case, have only extended this confusion. However, the possibility of her wrongful execution provides an excellent case study of how the Salem trials had grown so unruly and misguided by the end of 1692. Although historians cannot exonerate Mary Ayer Parker, perhaps they can acknowledge the possibility that amidst the fracas of 1692, a truly innocent woman died as the result of sharing the unfortunate name “Mary Parker.”

Mark Rice chose to examine the case of Margaret Scott, a stereotypical witch accused and tried late in the crisis. Mark showed that precisely because she was a classic witch, accused of maleficium (bewitching her neighbors’ livestock and children) as well as of spectral attacks on the afflicted, her fate was essentially sealed by the fact she was tried after the Court of Oyer and Terminer had come under sharp attack from critics of the court’s seeming reliance on spectral evidence.

Mark Rice, “Specters, Maleficium, and Margaret Scott”

Until recently, the story of Margaret Scott, executed September 22, 1692, as part of the Salem witch trials, was a mystery. With the discovery of depositions related to her trial, it is now possible to use the names, places, and events mentioned in the court records to finally discover Margaret Scott’s story. The information yielded by these documents shows that Margaret Scott was a victim of bad luck and even worse timing. These two aspects, more than any supernatural forces, led to the demise of Margaret Scott.

Margaret Scott fits the stereotype of the classic witch identified and feared for years by her neighbors in Rowley, Massachusetts (a small town to the north of Salem). Margaret had difficulty raising children, something widely believed to be common for witches. Her husband died in 1671, leaving only a small estate that had to support Margaret for years. Margaret, who was thus forced to beg, exposed herself to witchcraft suspicions because of what the historian Robin Briggs has termed the “refusal guilt syndrome.” This phenomenon occurred when a beggar’s requests were refused, causing feelings of guilt and aggression on the refuser’s part. The refuser projected this aggression on the beggar and grew suspicious of her.

It also appears that when Margaret Scott was formally accused, it occurred at the hands of Rowley’s most distinguished citizens. Formal charges were filed only after the daughter of Captain Daniel Wicom became afflicted. The Wicoms also worked with another prominent Rowley family, the Nelsons, to act against Margaret Scott. The Wicoms and Nelsons helped produce witnesses, and one of the Nelsons sat on the grand jury that indicted her.

Frances Wicom testified that Margaret Scott’s specter tormented her on many occasions. Several factors may have led Frances to testify to such a terrible experience, including her home environment and its relationship with Indian conflicts. She undoubtedly would have heard first-hand accounts of bloody conflicts with Indians from her father, a captain in the militia. New evidence shows that a direct correlation can be found between anxiety over Indian wars being fought in Maine and witchcraft accusations.

Another girl tormented by Margaret Scott’s specter was Mary Daniel. Records show that Mary Daniel probably was a servant in the household of the minister of Rowley, Edward Payson. If Mary Daniel, who received baptism in 1691, worked for Mr. Payson, her religious surroundings could well have had an effect on her actions. Recent converts to Puritanism felt inadequate and unworthy and at times displaced their worries through possession and other violent experiences.

The third girl to be tormented spectrally was Sarah Coleman. Sarah was born in Rowley but lived most of her life in the neighboring town of Newbury. Her testimony shows the widespread belief surrounding Margaret Scott’s reputation.

Both the Nelsons and Wicoms also provided maleficium evidence—a witch’s harming of one’s property, health, or family—against Margaret Scott. Both testimonies show evidence of the refusal guilt syndrome.

However, what sealed Margaret Scott’s fate was the timing of her trial and its relation to the witchcraft crisis. Evidence from the girls in Rowley coincided chronologically with important events in the Salem trials. Frances Wicom initially experienced spectral torment in 1692, “quickly after the first Court at Salem.” Frances also testified that Scott’s afflictions of her stopped on the day of Scott’s examination, August 5. Mary Daniel deposed on August 4 that Margaret Scott afflicted her on the day of Scott’s arrest. The third afflicted girl, Sarah Coleman, testified that the specter of Margaret Scott started to afflict her on August 15, which fell ten days after the trial of George Burroughs and Scott’s own examination. Additionally, the fifteenth was only four days before the executions of Burroughs and other accused witches who were not “usual suspects” and thus brought considerable attention to the Salem proceedings.

By the time that Margaret Scott appeared in front of the court, critics of the proceedings had become more vocal, expressing concern over the wide use of spectral evidence in the Salem trials. The court probably took the opportunity to prosecute Margaret Scott to help its own reputation. Margaret Scott’s case involved not only spectral evidence but also a fair amount of testimony about maleficium. Scott exhibited many characteristics that were believed common among witches in New England. The spectral testimony given by the afflicted girls further bolstered the accusers’ case. To the judges at Salem, Margaret Scott was a perfect candidate to highlight the court’s effectiveness. By executing Scott, the magistrates at Salem could silence critics of the trials by executing a “real witch” suspected of being associated with the devil for many years.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.2 (January, 2006).

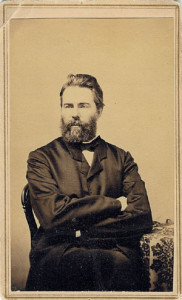

Mary Beth Norton, for 2005-6 the Pitt Professor of American History and Institutions at the University of Cambridge, has taught at Cornell University since 1971; her most recent book, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, was published by Alfred Knopf in 2002, with a Vintage paperback edition in 2003.