Margaret Ann Noodin

Bingwi-nanaandawi’iwe-nagamon

A Sandy Healing Song

1.

Anaambiig, anaamaabik

Under the water, under the rock

mikwendamang giizhgoog

we remember the days

mikwenimangwaa

we remember the ones

gaa mewinzha

who long ago

inosewaad, onosewaad

walked to and from

gichimookomaanakiing

the long-knifed American

zhimaaganishigamigoons

place of war, of distribution

mii baabii’owaad, mii zhigajibii’owaad

then waited, became impatient

bakadewaad miidash gawanaandam

hungry then starving

bedosewaad, niboowisewaad

walking slowly dying

gojigiiwewaad

trying to go home.

2.

Anaambiig, anaamaabik

Under the water, under the rock

mikwendamang giizhgoog

we remember the days

mikwenimangwaa

we remember the ones

gaa mewinzha

who long ago

gabeshiwaad akawaabiwaad besho

made camp in expectation near

gichimookomaanakiing

the long-knifed American

besho zhimaaganishigamig

place of war, of distribution

mii babaamademowaad, mii animademowaad

then crying away from there

animinizhimowaad miinawaa giishkishinowaad

ran terrified and falling in slices

nitamawaawaad, niboowisewaad

murdered, slowly dying

gaawiin wiikaa giiwewaad

never to go home.

3.

Anaambiig, anaamaabik

Under the water, under the rock

mikwendamang giizhgoog

we remember the days

mikwenimangwaa

we remember the ones

gaa mewinzha

who long ago

bagadinmawiyangidwa

made offerings to us

mitaawangaagamaagong, heséovó’eo’hé’ke

Sandy Lake, Sand Creek

ho’honáevo’omēnėstse biinish gichi-ziibi awyaang

we are standing stones and flowing water

gii noondawangidwaa, naadamawangidwaa

we heard them, we helped them

ezhi-inawewaad inawemiyangidwa

they were our relations

ganawenindizoyang endaazhi-bakaaniziyang

caring across one another’s differences

giiwe-gizhibaabizoyang apane.

spinning always home.

4.

Anaambiig, anaamaabik

Under the water, under the rock

mikwendamang giizhgoog

we remember the days

mikwenimangwaa

we remember the ones

gaa megwaa

who right now

gabeshiwaad akawaabiwaad

make camp in expectation

oshki-gichi-akiing

in a new global space

gimoozikaw-zhaabwii-niimi’idiwaad

a sneak up dance of survival

onaakonigewaad ezhi-nagamowaad

they decide how to sing

nanaandawi’iwe-nagamon

a healing song

gaawiin wiikaa wanendamosiiwaad

never forgetting

apane bi giiwewaad

always coming home.

This poem connects the memories of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, which occurred between October 1849 and January 1850, when 400 Anishinaabe men died of starvation and freezing; and the Sand Creek Massacre on November 29, 1864, which took the lives of at least 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho families and soldiers. It was written first in Anishinaabemowin with select Arapaho and Cheyenne place names.

Margaret Noodin, 2015

Sara Marie Ortiz

Oil

I began to write at the age of fourteen. But I think I’d always told myself, and others, stories. Stories about the world as I saw it. Stories about the world as I wanted it to be. Stories to shock, and inspire awe, or captivate, stories that told a version of the truth which helped me to feel like my spot of Pueblo child-earth was a little less inconstant, a little safer, a little more mine somehow. A lesser known ‘fiction’ would be the one I’d ultimately come to know as my adolescence and young adulthood as a working Indigenous woman writer – a ‘fiction’ that I’d dared to begin writing as only a child.

Of thee I sing

strange fruit

Colonel Chivington

Evans and all his many ghosts assembled there

Spring wind rising

Driven from the land

Not really

The ghosts sing a song of me

I lied as a little girl. A lot. I think these earliest fictions, which were sometimes the only truth a child like me knew, were actually early forays into the genre I’d ultimately be rooted in—creative nonfiction. I think my own version of truth-telling, and the ways in which it became food, scepter, and guide wasn’t just a survival mechanism, it was my way of orienting myself in time and space and granting myself ownership over my own Indigenous life, selfhood, and vision. I’d soon learn that the people I emerged from, Pueblo people, had all told stories in this way—not just in order to survive, but to sing the world and everything in it into being.

Sing a song of us

But this is not a scary story to tell in the dark, no,

this is our morning song, our staying awake through the night song,

our survival-somehow song

We were not driven from this land

We were not relocated

Not really

The enterprise failed.

Our brown bodies are only half the story.

The great-great half-Pueblo granddaughter of a businessman and mill owner named Van Winkle who owned slaves and built a good deal of the infrastructure of NW Arkansas in the civil war era. Heroin and crack-addled caretakers. A venerated alcoholic Pueblo poet-father. A manic, yet dutiful, actress-turned-lawyer mother. A part-Navajo, part white schizophrenic baby brother. A girl child born to the brown girl at fourteen. Crack deals gone bad. Murders and missing women. The vastly beautiful New Mexican landscape—a rapture unto itself. Constant travel, across Indian Country, and even a little abroad. Stories. So many. And ghosts. So many. How could I not write them?

#Blacklivesmatter

Denali or McKinley

Either way

Drilling for oil in the arctic

Every plastic bobble

Every cell phone

Every pen

A legacy

Oil into plastic

Bones into oil

The ghosts of them dance and rise up

I can’t say that I have a ‘favorite poet’; books, their contained poems and prayers, and the scribes who get them down—they are all nourishing to me, sometimes beautiful and terrifying in just what their little forms mean. I left Santa Fe for Seattle; left most of my beloved books behind, along with my daughter, my mother, my little brother, my land, my rivers, and my sky.

They are one fabric of voice and loss.

I miss them all terribly.

Some of the writers whose names rise, and whose poem-song-prayers continually strike me:

Mei-mei Bersenbrugge

Arthur Sze

Natalie Diaz

dg Nanouk Okpik

Lorca.

I am impelled by, dragged along the seam of, language. Its history and its mysterious interplay, its codices, and vertices of light, that glimmer and wane—I am enrapt within and by it. It haunts. It nourishes. It maddens. It is all we have. Silence, void: they, too, are language. I aspire to that, according to Aristotle, ‘highest good’, a greater depth and breadth of knowledge. I want to know the seemingly unknowable, even say it a little, if only just that and sometimes. I want to stare into the heart of darkness, cross the river Hades, return with dried orchids placed on the graves of men I dared to love, let love me, and leave. I have known so many broken-hearted children who would be fathers. I have known so many fathers who would be ghosts, and live many years, without knowing that they were. I am driven forward, always, by a wind that says “tell your story, child. It will be enough after all.” Film, music (it is proof), driving, dreams, conversations, things heard in passing, flight, bad TV, emails, letters, texts, posts to friends, sounds of birds, and every sort of light: it is all food, it is all a bit of balm and song. The Muses – they are mad, and they are many. I have been blessed to meet a few. They don’t visit me as often as they once did. But my door is always open.

They never left

We never left

We will never leave

A la Silko – stories, they is all we are.

They is all we have.

They is all we were, are, and will be.

Blood and bones into oil; oil, bones, and blood back into light.

Hashtag: we are still here

we are still here

we are still here.

I talk a lot. Most likely too much. I have a really big mouth, so in a way I’m always partially within that architecture of ideation and rendering the world into more suitable reels of omni-sensual experience. If I don’t write them, I say them out loud, and that can get me in trouble. I don’t always write in earnest and all the time. I’m not what you’d call ‘a disciplined writer’ and I’ve never been. I usually write at least a little each day or night, usually on my smartphone, little notes, little word and world ephemera just to remind myself of little things, and to orient myself in time and space.

Pueblo child

Born of Methodist and Baptist kinfolk too.

No turnin’ away from the hallelujah sing-you-clean

but never clean enough spirituals of old.

Child come up in the time of MTV blinking awake,

gangster rap, the LA riots, and memories of 1680

too far to cull back and through the gentle clap and clamor

of latch-key child PSAs, late night trips to this locale or that, and school

days on the west-side too near where all those missing and murdered brown women lay.

These bits come when they come, ebbing into more evolved forms as they need to, regardless of the time of day. I think there were periods where I wrote more at night, and then others when I wrote mostly in the day. I seem to write with the same urgency and lucidity regardless of where I am when I most need to write. When I’m overworked, super stressed, taken by a less-than-fruitful ennui, inundated with non-sensual language, underexposed to new or stimulating ideas, or forms, gone too long away from home, when I go hours or days, even months, without being allowed the space and time to really engage in the process of writing, not being allowed to enter fully into a deep enough, protected, familiar, cathartic, hyper-acute, and hyper-active sort of reverie, that ends up producing much of my work, I’m a pretty terrible person. I stop dreaming. I want to take a black Sharpie to the walls of the world. Everything goes a matted thatched shade of dark. But when I emerge from that dark? Like a group of survivors of a zombie-attacked world, just emerged from an underground compound; what else do you do? You begin again.

Simon Ortiz

From Sand Creek: A Vision for Peace and Continuance

Violence is even

beautiful.

Mastery

of pain

is crucial

to this work.

A senator

did not need to hawk

Biblical phrases.

It was

all ordained and certain.

They clamored for salvation,

those stalwart victims

sent

as messengers,

already avengers

fore-running justice,

to Colorado.

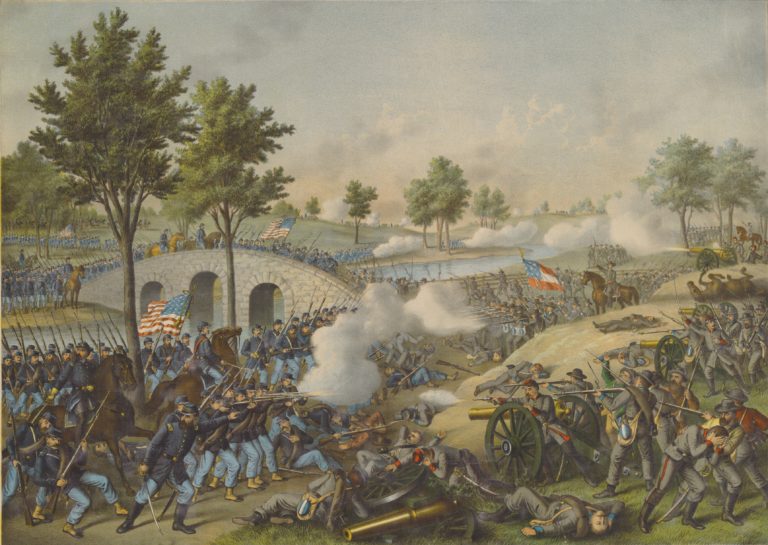

One should know better. In 1974 when I learned about the November 29, 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, I didn’t know anything. In 1941 when I was born, the U.S.A.—my nation I was told and had come to know as fact—was at war. In 1974, the U.S.A.—I’d been told a million times I was a U.S. citizen–was still at war. In 1864, when the Arapaho and Cheyenne were massacred at Sand Creek by a citizens’ militia called Colorado Volunteers and U.S. military soldiers from Fort Lyon, my grandfather, Mayai-shaatah, was 9 years old. And also, yes, that was when the U.S. was fighting two wars: the wars against Indigenous Americans—known popularly as “the Indians”– and the war against its own brothers and sisters which it called the American Civil War.

One should know better is not a dictum, as far as I know, but it can serve as one when I think about the United States of America and war. The nation was born in war when it revolted against its British Empire origins and mother homeland, and it continues in war mode today in Afghanistan and perhaps soon in Syria and in almost countless instances of conflicts stemming from invasions, occupations, conflicts, police actions, and so forth over the past years. War has been endless in our nation’s history; it’s almost as if there’s never been a time in my lifetime when there has been no war. War and its trauma, even when it’s not happening in our front yard or backyard, is vastly negative. The greater part of our culture and society is experiencing and suffering PTSD—do you know that? Do we know that? Do we want to know that? Should we know that? I think so. We have to in order to address PTSD and its root causes.

Aacquh—Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico—was destroyed in January 1599 AD by Spanish invaders led by Don Juan de Oñate during the initial colonial conquest of the Indigenous Southwest. According to Spanish records, 800 Aacqumeh people were killed, and the Pueblo was utterly destroyed. It’s a long time ago in some respect, but it’s not really. Remember my grandfather Mahyai-shaatah who I mention above? He was 96 years old when he passed away in 1951. That means he was born a few years before the American Civil War in the 1860s, and in fact he was born 9 years before the Sand Creek Massacre. So in the way of calculating time and noting its passage in the manner of speaking within the oral tradition, my memory of the Civil War and the Sand Creek Massacre is fresh because of Mahyai-shaatah, my grandfather. I can almost literally say I have an intimate sense of recall when I put it into the context of oral tradition and how one is placed within the narrative structure and power of Indigenous oral knowledge. That’s a validation that’s needed but not provided in scholarship which, as a result, limits Indigenous knowledge to some degree since dissertation and research committees do not fully recognize and accept oral tradition knowledge as equivalent to Western-derived knowledge. If any people have been affected directly by violent and traumatic warfare in the Western hemisphere, it has been Indigenous American people more than other cultures and communities.

Perhaps I shouldn’t say this but I will in order to make a point of it: violent and traumatic warfare has been so endemic to Indigenous American people and their lives that it has become virtually normalized. Part of it has to do with the image created by the narrative recitation of “Indians,” a term that is defunct even though it is still used presently as an entirely valid construct of fact. Upon initial Spanish European arrival, there were innumerable tribal communities of Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas, living across both continents of the Western hemisphere. Population figures range from 65 million to 140 million people upon the arrival of Europeans i.e., Columbus’s landfall in 1492 AD, and these millions were not known as “Indians.” Columbus’s chronicler records show Columbus recognized and identified the Indigenous people who first greeted him and his men as “gente en Dios.” People of God. En Dios soon became bastardized as in dios. And in dios became indios that as a term was used to identity all Indigenous peoples in the Americas thereafter. “Indians” later became the general derivation that has stuck through the span of more than 500 years. In any case, pliable terminology became an easy and convenient way to construct imagery that served colonialism more than it served to protect the integrity of Indigenous land, culture, and community. “Indians” is inaccurate, very prone to expropriation, easy to undermine since by inference it’s more abstract than actual and solid, and the term has very little semantic basis on sound legitimate knowledge. Therefore imagery regarding Indigenous people as “Indians” is suspect and prone to convenient use that is detrimental, dismissive, misleading, and damaging. Such use of imagery affects Indigenous people negatively because horrendous events like the Sand Creek massacre may not be understood and not seen in terms of the horrific, traumatic, and devastating experience it was but rather something constructed by Hollywood films or exaggeration or even fiction. No, the massacre was not a Hollywood production nor an exaggeration or a literary fiction. The Sand Creek Massacre was real, and we have to deal with it as reality!

Violence and trauma transform and transform, and change takes place. On and on until changes become a force that one doesn’t know what to do with. Society and culture are formed in the modern age by past historical experiences that are practically impossible to understand because they happened so long ago that one has no cognizance of them. Yet despite that, one tries to make sense of present day patterns of social behavior and structure, usual and ordinary relationships between people, responsibilities that are guided by local, state, and federal laws. And even when one doesn’t truly comprehend society and culture, there is acceptance and going along with public or common practice and belief.

When Indigenous people like Maiyai-shaatah were born in the mid-1800’s the American republic was not 80 years old yet. Settlement in the Americas was in full swing. The Spanish had been in the Americas since 1492, almost 300 years already! Northern Europeans like the British and French were coming ashore as immigrants since the early decades of the 1600’s, for 200 years along the eastern seaboard from present-day North Carolina to Nova Scotia. With almost no major cognition of violence and trauma, Europeans were becoming Americanized rapidly. Since the goal of Euro-Americanism was acquisition of gold, slaves, and resources useful for Europe, the overriding impulse was determined by the New World’s wealth because of the power that would result upon conquest: gold, slaves, resources.

Looking for Billy,

I knew he wasn’t anywhere

nearby.

Like his words,

he could be anywhere.

He was the shadow.

Memory was his lost trail.

West, then south, then east,

a swirl of America

in his brain.

Looking for shadow,

he could be anywhere.

In a way, democracy, like religion, could be anything. Or nothing. As Indigenous children, we were sent to school like everyone else in the nation. It was the law. It was U.S. policy with reference to Indigenous people. And the U.S. government was enforcing/enacting the law by requiring Indigenous children to go to school. Education was the law; it was required. However, since it was the law and the law governed “Indian reservations,” as Indigenous children we were doubly required to go to school. It was against the law not to go to school; it was against the law not to become educated. For me to not go to school at six years of age, my parents and I would be defying the nation’s law. Our parents-guardians would be law breakers. Our own concept of Indigenous tribal law said the law served the people: it was security, safety, preservation, health, and wholeness. Law made sense; so the people obeyed. It was like living on the reservation: that’s where “Indians” were supposed to live. That was the law: reservations were where “Indians” belonged. Not in the cities, not on state lands, not anywhere else but on the “Indian rez”. That was the policy. We had to live by it. The rest of America believed that was the way it was. It was inconceivable it could be any other way. We, as Indigenous people, had no choice.

You wouldn’t believe it but it made sense to go along with the federal government. They, the officials, i.e., the bureaucrats, had tremendous hope and patience and a special cynical faith—well, they couldn’t lose either—that willed them to believe “in the Indians”. No matter what. No matter what one Indian agent said, God will carry us through. That’s God’s will. We have to have the determination that God’s will will carry us through. And he’d repeat it. Believe in God, he’d say, and the Indians. In the 1930s, the government planners built the irrigation system on our Acoma reservation. It’s our duty, I’m sure the Bureau of Indian Affairs “Indian agent” said. Ideally, that was the belief in the belief, consistent, persistent. Congress, Senators, bureaucrats, the President, even the missionaries believed in the belief. In the 1860’s, it was to clear the prairie of the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Pawnee, Blackfeet—the “Red Devils”, as newspapers would have it—and in the 1930’s it was to build an irrigation system to water “Indian land”—land of the same Red Devils—all done in the name of believing the belief. Yes, even the parish priest had in the church sacristy WPA photos of Aacqumeh men and boys working on the irrigation system at home on the reservation.

Billy believed beyond the belief. He was always trying to get away from the VA hospital. Run away. Just leave. He’d be gone for a day. Or two or three days. He’d make it to Pueblo or Colorado Springs or Trinidad or another town not far away, and they’d bring him back. Once he was gone for a week. Made it to Kansas I heard. The police saw him, I’m sure, wandering around downtown in that slow rhythmic lope he had. And he was back at the VA locked up in Lock Ward for a couple of days looking lost, trapped, and empty. And, soon, Billy was back outside wandering around with his handy empty smile. Of all the guys at the VA hospital, Billy was the only one who was always trying to get away. That’s what I mean by Billy believing beyond the belief. He knew he could live outside the confines of the reservation the VA joint was. He just knew he could. One day, two days, or a week of living beyond the belief. That was all Billy needed to believe in forever.

It made sense for Indigenous people to believe the land with its animal and plant life was enough. In fact, it was more than enough. As people, they were related to it as mother, father, sister, brother, grandma and grandpa; they believed, just like Billy, it provided everything. Land, people, animals, plants, everything was sustainable. Creator—Dzah-yaa-yuutyah—provided for everything and everyone in all creation. Sky, land, ocean, tree, bush, weed, insect, fish, animal, molecule, atom, all bits and pieces of creation, nothing was left out, everything was sustainable. Connections, relationships, responsibilities, obligations, laws, understandings, common sense, great ideas, little ideas, all were part of the mix. Billy was part of it; he believed in forever. Society was part of him; he was part of society. He wasn’t Indigenous like Native people of the Americas but it didn’t matter; he was part of the land, culture, and community. That was the main strength he had—his innocent belief in the connections he had to everything. It didn’t matter what or who. Repeat: it didn’t matter what or who, just as long as he was connected/related to everything contained in the land, culture, and community.

In the Dayroom,

the Oklahoma Boy sits

sunken into the arms

of a wooden and leather couch

that has become his body.

The structure of his life

and the swirl of his mind

have become lead.

There is beauty

in his American face,

but the dread implanted

by the explosive

in Asia denies it.

The life he now matters by

is pushed away without pity

by the janitor’s broom

which strikes his shoe.

Only the corners

of his eyes and the edge

of his shoe know the quality

of the couch he has become.

It is the life he has submerged

into, a dream needing a name.

He has become the American,

vengeful and a wasteland

of fortunes for now.

We feel we have wasted nothing as Americans. There is no wasteland. Not a bit. It is a belief. Plenty means plenty. The American Dream is not a dream at all but a principle beyond anything we have ever known. It is patriotism unneedful of understanding or comprehension. Or acceptance. It just is. That’s all. Simple as simple, something we simply don’t understand. As Americans, belief is first, then everything follows. Even if failure is fate, it doesn’t count. Should fate be failure, then we don’t have to win. Victory is American despite fate as failure. We have nothing to prove. Even when we have nothing to lose.

America is not a dream at all. We have arrived. Our schools teach that. There is no choice. In fact, we don’t even learn to question. Accept, accept, accept, accept—that’s the order of the day. That’s the only order. On the “Indian reservation” I went to a day school run and paid for by the federal government. Obey. Obey. Obey. Obey. Sounds like accept, accept, accept, accept doesn’t it? In fact, that’s what it means. Same thing. “Indians” were to learn to be Americans. Nothing more. Nothing less. We learned the ABC’s. That’s the way success was spelled. Nothing more. Nothing less. ABC spells success. Learn English: writing, speaking, no more, no less: that’s success.

Accept. Obey. Learn ABC. Learn success. Nothing more. Nothing less. Especially learn English. I did. Learn to spell. We did. Learn well. I did. Learn success. We did. ABCs spells accept, obey, learn, success. Our grandmothers tried to shelter us behind their dresses, behind their knees, within their homes. Call them teepees, call them hogans, call them stone and mud, call them huts, call them our homes. We lived in them. They were home. Nothing more, nothing less. Our homes our lives. Our way our own. Our hearts, breaths, names, spirits. Our past, our future. Our heritage, our destiny.

What more could America be. A natural land of plenty. Land with dirt, rivers, valleys, mountains, deserts, canyons, oceans. Forests, prairie grass, cactus, willows, swamp grass, seaweed. Sky so wide, winds that blow for days, hurricanes to bring water to the land, rains and snows and mistiness for days on end. And sun so plentiful, constant, bright, brilliant, shining, forever without end. Land upon land, expansive for miles and miles. What more could America be? From seashore to seashore: east west north south. Galaxy to galaxy, we lived within and without. What more could America be is not a question at all; it is wonderment and awesomeness beyond our short memory and constant forgetfulness. A vision that beholds us, waiting for us to return its gaze so we can both see ourselves in the other.

I wish now I talked with the Oklahoma Boy about the dream that America isn’t. The dream he left in his dry homeland back when in Oklahoma when he went to Vietnam. The years ago sand and dust and wind and time gone that are still there. Waiting. Yeah, waiting for him to return. The rivers that ran dry before he was born and grandma and grandpa remembered for him and maybe told him and his sisters about them a time or two or more. Many times I’m sure. The dreams they knew. Dreams poor people have. The ones we hold precious even though we may have thought they were just lies. That’s okay though. That dream is real even if it’s hard to believe because it’s hard to keep track of. That’s part of the dream though we must remember. Unfortunately—fortunately also—the way we learn is by missing the sand, dust, constant dry wind, the rain we feel even when it hasn’t fallen for years. Believing is believing facts–and lies too sometimes. Yes, lies too that we come to bet our factual lives upon. No matter what we feel and what we must deal with, the dreams we have do matter, especially the dreams the Oklahoma Boy wanted to tell me but didn’t.

Don’t fret now.

Songs are useless

to exculpate sorrow.

That’s not their intent anyway.

Strive

for significance.

Cull seeds from grass.

Develop another strain of corn.

Whisper for rain.

Don’t fret.

Warriors will keep alive in the blood.

Genocide is genocide. It is a fact. There is no other way to look at the death of a people caused by another people who are uncaring, unfeeling, unwielding, unrelenting. Death of Indigenous people of the Americas took place. Death was not caused by the Indigenous people themselves. It was caused by another people who coveted the lands and resources of the land that Indigenous people lived upon. Genocide was caused by a senseless hatred of the love human beings have for human beings. It made no sense to kill people because of love, some said. It makes perfect sense if it keeps people safe, others said. Which way do we choose? No one knows directly. Or say they don’t know. But we do know genocide is wrong and evil. And that’s all we need to know.

As a human culture and society, we are responsible for each other on this planet Earth. We have no choice but to be responsible for one another. That is called obligation. Human beings taking care—great care—of each other. Food, shelter, clothing, respecting, honoring, protecting. When we have no choice in the matter of relationships with each other, that sense of obligation comes to the forefront. Even enemies know this; they fear and hate and detest as a result. Obligation: caring for others; seeking to feed, clothe, and shelter others is not a foreign concept. A mother gives birth to a child, and everything is obligation from then on. The infant is dependent on the mother for nourishment both physically and emotionally; human nature begins at the very moment an infant child cries for sustenance and the parent has no choice except to reply instantly to her child’s cries, pleas, demands for sustenance. And vice versa also, the parent is dependent upon the children’s needs and requirements. Responsibility, obligation, interdependency is the sacred nature of human culture and society.

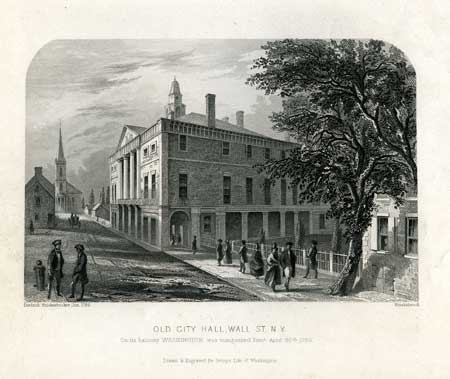

When Black Kettle went to Washington, D.C. in 1863 to meet with the U.S. government and its president, Abraham Lincoln, Black Kettle was presented with a U.S. flag that symbolized the responsibility, obligation, interdependency and the sacred nature of human culture and society. A year later in November 1864, the genocidal attack on the Cheyenne and Arapaho took place in sheer, utter, and absolute violation of the sacred nature of human culture and society. During the attack, that symbolic flag flew from Black Kettle’s lodge. The elder had raised it because he believed the U.S. flag would protect him and his people. In fact, one can even say Black Kettle believed in the vow the U.S. government had made to him and Indigenous people across the vast lands they lived upon. I’ve never read or heard of remarks or comments President Lincoln may have uttered when he was told about the massacre at Sand Creek. Perhaps the U.S. President never said anything since this was the same era in which he ordered the mass execution by hanging of 38 Indigenous warriors who were protecting their land, culture, and community in Minnesota territory. As for us, we must remember this: responsibility, obligation, interdependency is the sacred nature of human culture and society. We must always remember this, no matter what.

In this remembering is the vision for peace and continuance that we must live, no matter what. Repeat: in this remembering is the vision for peace and continuance that we must live, no matter what.

Simon J. Ortiz, Tempe, AZ

September 17, 2014

Frances Washburn

A Dry Thunder

Brown grass burned brittle in the fierce summer heat crunched beneath their feet as Becca followed her father up the steep hill to the little church. Overhead the sun glared from a brassy sky, while the usual thunderheads hovered on the horizon, grumbling in the distance. Sweat beaded on the back of Becca’s neck, runneled down her spine to soak the waistband of her jeans.

Lee’s faded brown uniform shirt showed dark sweat circles beneath the arms and a dark tee patch across the shoulders and down his spine. The wind picked up, blowing dust from the mass grave outside the church, rattling dry weeds.

Lee sat down on one side of the narrow cement line that formed the rectangular perimeter of the grave patting the ground beside him. His daughter bent her knees and sat on the hot ground. A grasshopper leaped onto her knee, observed her, and hopped away.

“Dad? Are all those people really buried under here?” Becca asked. “It doesn’t look big enough.”

“You’d be surprised how many people you can put in the ground if the hole is deep enough. And if you fling them in any old way,” he answered, looking not at the grave but at the thunderheads building in the west. “Shhh. Listen.”

The wind rising and falling found a voice in a loose shingle on the church roof, whistling and howling. Distant thunder grumbled. Down on Route 27, an old Chevy station wagon with a loose muffler bumped over the pot holes in the broken blacktop, going south. A blue bottle fly licked sweat from Becca’s arm before she could twitch it away.

Lee lifted his cap, letting the wind ruffle his thinning gray-streaked hair, reached out and tousled Becca’s hair.

“Why are we here?” He asked.

Becca knew he expected her answer to be more than the casual, factual, “because we come up here twice a year.” She remembered other visits over the past thirteen years of her life, walking up the hill through snow ankle deep, or slipping in mud, or when the grass was green and a breeze blew softly upon her face, when her sister, Connie was still alive, chattering, running, and jumping alongside her father, and her father, rarely speaking, always sitting on the rim of the grave, and asking that same question.

“Why are we here?”

“Because they were here first,” she answered. That was not right answer; she knew that, she felt like she was getting no closer to what her father wanted her to say, to know, to understand about this sacred place. He asked her that question often, not just here on the top of this lonely hill.

****

He asked that question when she sat beside him, outside the pen of birds as now and then, not often, he wrote a few words with a black ball point pen in the spiral blue notebook he held in his lap. Last time he asked the question outside the pen, as they sat on grass burned as brown and brittle as here, she answered “Observing,” and his eyes has widened, his glance had caught hers, but he hadn’t answered. She didn’t expect an answer. She believed there might not be an answer. The question intended her to think deeper, not to find a conclusion.

She had glanced at the words he had written in the notebook: Martha and George. That was the name the workers at the refuge gave the tamest two of the nineteen trumpeter swans brought to Lacreek from Red Rocks, Montana six months earlier, the last of the trumpeters that all the specialists believed would be extinct soon. Lacreek would be their last refuge. Endangered species, doomed, unless Lacreek could get them to breed, get the females to sit on their eggs until they hatched, get the chicks to live, grow to adulthood, mate, and continue the cycle.

****

The creek wound around the base of the hill, dry, lined with brittle brush and squat trees with tired gray-green leaves. More than seventy years ago, they had tried to escape up that creek, gunned down, bludgeoned, old men, women, and children, their red blood spilling out on the white snow, their screams and cries carried on the wind. Distant guns thundered.

Becca stood, stretched, moved back to sit on the cracked cement church steps in a narrow strip of shade. Half a dozen brown beer bottles nestled in the weeds to one side, the labels faded and peeling. She looked to the thunderheads in the west that seemed no nearer.

Lee stood, removed his cap and wiped his hand across his forehead, turned to Becca.

“What do you hear?” he asked.

The wind howled beneath the shingle on the church roof.

“I hear their voices in the wind,” she said.

He nodded.

“Looks like we won’t get any rain,” he said, “those clouds are going south. Let’s go.”

At the bottom of the hill, he stopped where a sign lay on its face, toppled over in the weeds and the dirt, turned it over. It read only, “Wounded Knee Battle Site,” in faded black letters on a white background.

“Not a battle,” he said. “A massacre.”

Becca slammed the car door three times before the latch caught.

Lee cranked the engine that whined and complained before the motor turned over. He put the car in gear, circled it, and drove slowly away, dust billowing behind them.

“I’ll buy you an orange pop at the Trading Post,” he offered.

“Okay,” she said, her dry mouth already beginning to water.

Distant thunder grumbled, a harbinger of rain somewhere else.

“Dad,” she asked, “are we an endangered species?”

“Not yet.”

Michael Wasson

In Winters, as Ghosts

any lack

of light might do

had we the opening

to the sky

where the snow begins

to fall

on all our daughters

which is to say

I might find anyone of them

among the dead as every bird

is crushed in the throat

of a direction leading south

& my mother said

there’s no hell here

her eyes black

a moonless night still scatters enough

moonlight on our skin

*

there is a hole where we are

up through my head some witness

left between that & tonight

come father me

again the body begs

I’m dreaming of you

shredding your

c’ic’ál’ into a single

metal jacket that is

your eyelids unblinking

& you’re dreaming

of me

aren’t you the shadow of my father

are you not?

so the winter speaks

a memory

of blood

carried like a heavy rope

in the failing

of hands & look

you’re dead still

& bared arms

wait

with nothing of flesh

but a ghost

watching the snow break

apart by gathering.

Lit in the Mouth [Or for the Woman Who Died of Song & Loneliness]

There we are

the boy might say

to the bone

white in the night méetmet q’o’ manáa

hinú’ kem kaa páayno’

& he stares silent as how one might

find a body left at the edge

of a field

meeting

a burned tree is what he’s been

ashamed to know

i

Open your ears

for you are nothing

without this sound

‘ee himc’íyo ‘áatwaynim

she will hear you

when you move ‘ee ‘iim

even when you are

nothing

like a ghost

i

kál’a c’ic’ál’ hiicéem kiyéewkiyew

I confess I’m young

& you take a flame

to my tongue

c’ic’ál is lit in the mouth c’ic’ál again

‘ipnéetetmipniye was a bluing

vessel tied from the back

of the throat

to the manáa yox ̣ hice?

inside my confession

i

manáa yox ̣ hice? asks the naked pine

above me manáa yox ̣ hice? asks the star buried

beneath a haze of moonlight manáa yox ̣ hice? asks the bird that forgot

to ignite an evening of birdsong manáa yox ̣ hice? sing the crickets

with small mouthfuls of night manáa yox ̣ hice? ticks the slight burn

of the sunset a mouth pauses

in awe

i

c’ic’ál hiicíix kiyéewkiyew

sometimes to remember this living

we let a word

fire from the opened hole in the face

& tell me how to swallow what light does

to the tongue at rest

i

kúnk’u hinwíhna because death is what shadow does

to the body climaxing

& hidden in the dark

t’úmm kál’a ‘íske naqsníix & because that sound is just like another

single dusk draining off

its slow-motion blood

máwa pehíne? máwa pu’úuyiye? because when is the best question

I can muster

kál’a sáw is a silence

you’ll never forget & hit’úxnime because she burst

into a din

& sáw sáw sáw sáw

because ‘ipí ‘áatway kál’a c’álalal c’álalal & who can say

they’ve been so close

to a loneliness like this before?

i

Who is it that the dead

remember? the moon

finally asks me

i

Say pá’ipciwatx ̣

hiwe’npíse could be herself singing

& say konó’

‘ipnéeteti’nke could be she sang

herself to death & remember wéet’u’

máwa hinéeshewtuk’iye hinmíitx was that

she never caught up in singing herself

& so there we were again

us alone again after dusk.

* this poem borrows language from kiyéewkiyew (Katydid), a nimíipuu story told by weyíiletpuu

Mouthed

But is it not

for the flesh

nor the prayer

you recite in the house

outside an autumn

rusting the edges

of the dead leaves?

if not to grieve

history burning

the space between

our bodies

our long hair

still sewn into

our stripped scalps

then what?

is it not for

the suffering?

tell me it is

for the emptiness

like this plea caught

in the air of a town

with no name

a land ghosted

with the ashes

plumed by the war

so are we not

the ash? is it that we’re

the names dissolving

into your throat

pleading for your life

us a sound like a dark

blued field crowded

with katydids

in their sáw sáw

sáw sáw herding

you to your loneliness?

& is that not you desperate

for relief & mouthless

seeking for any

exit of your body?

& is that not you

I hear drowning

in the living room

hunched down to what

we never called god

to kill the clock

god please the clock

to pull back the hand

to unwind your life

back together again?

is that scope of light

pointed to your skull

clear-eyed enough

in its hunger? is it

about to swallow the dark

of our bodies &

claim boy it’s all in

your head now

don’t be scared my son

O answer me please

so call it beauty

call it the emptiness

left with a twist

of smoke unbraiding

from a hot chamber

call it our survival

to carve a clean thread

through the head

of a silenced deer

& call its full heart

in my hands an ache

as I’m remembering

how to part

the skin & sing properly

that yes it gave its body

to us in our appetite

remember us

for our nourishment

to reduce the burning

plea into a resin

of blood drying

in my fingernails

remember please this

opened hole

burst from your head

here in the house

crushed by autumn

can only be yes

your closing word.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Crisosto Apache is an enrolled Mescalero Apache member from New Mexico. He is an alumnus from IAIA (AFA 1992 / MFA 2015) and Metropolitan State University of Denver (BA, 2013) in English and Creative Writing. His work is published in Future Earth Magazine, Black Renaissance Noire, Yellow Medicine Review (2013/2015), Tribal College Journal, Denver Quarterly (Pushcart Prize Nominee 2014), Toe Good Poetry, Hawaii Review, Cream City Review, and Plume anthology. Crisosto also appeared on MTV’s “Free Your Mind” ad campaign for poetry (1993). His work includes Native LGBTQI / “two spirit” advocacy and public awareness.

When Byron Aspaas writes, he creates stories using vivid imagery of landscape which is etched with experience upon white space. Byron is Diné. He has earned his BFA and MFA in creative writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts. His ambition is to incorporate his writing toward teaching and becoming a storyteller. His work is strung through journals and anthologies such as RedInk, Yellow Medicine Review, 200 New Mexico Poems, Weber: The Contemporary West, As/Us: A Space for Women of the World, Semicolon, and Denver Quarterly. Byron wants to influence readers along this literary journey. He is of the Red Running into the Water People and born for the Bitter Water People. He resides with his partner, Seth Browder, his three cats, and four puppies in Colorado Springs. Currently, he is working on a memoir.

Poet, photographer, and scholar Kimberly Blaeser is the current Wisconsin Poet Laureate. A professor at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, she teaches creative writing and Native American literature. Blaeser has authored three poetry collections—Apprenticed to Justice, Absentee Indians, and Trailing You. Her poetry and scholarly essays are widely anthologized, and selections of her poetry have been translated into several languages including Spanish, Norwegian, Indonesian, Hungarian, and French. She is at work on a collection of “Picto-Poems.”

Lance David Henson is Cheyenne, Oglala, and French. He was raised on a farm near Calumet, Oklahoma, by his great-aunt and uncle, Bertha and Bob Cook. He grew up living the Southern Cheyenne culture. He served in the U.S. Marine Corps after high school, during the Vietnam War, and is a graduate of Oklahoma College of Liberal Arts (now University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma) in Chickasha. He holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Tulsa. Lance is a member of the Cheyenne Dog Soldier Society, the Native American Church and the American Indian Movement (AIM). He has participated in Cheyenne Sun Dance on several occasions as both dancer and painter. Lance has published seventeen books of poetry, half in the U.S. and half abroad. His poetry has been translated into twenty-five languages and he has read and lectured in nine countries. His readings include the One World Poetry Festival in Amsterdam, the International Poetry Festival in Tarascon, France, and the Geraldine Dodge Poetry Festival in New Jersey. He has co-written two plays, one of which, Winter Man, had a successful run at the La MaMa Experimental Theatre Company. His play Coyote Road played to sell-out audiences in Versailles, France, in December 2001. A new remix of a jazz and poetry CD titled Another Train Ride (1999) has appeared in collaboration with Brian Eno, titled The Wolf and the Moon, from Materiali Sonori, Milan, Italy (2001).

Toni Jensen is a Métis writer whose first story collection, From the Hilltop, was published through the Native Storiers Series at the University of Nebraska Press. Her stories have been published in journals such as Denver Quarterly, Ecotone, and Fiction International, and have been anthologized in New Stories from the South, Best of the Southwest, and Best of the West: Stories from the Wide Side of the Missouri. Her short story “At the Powwow Hotel” won Nimrod International Literary Journal’s Katherine Anne Porter Prize for Fiction. She teaches in the programs in creative writing and translation at the University of Arkansas.

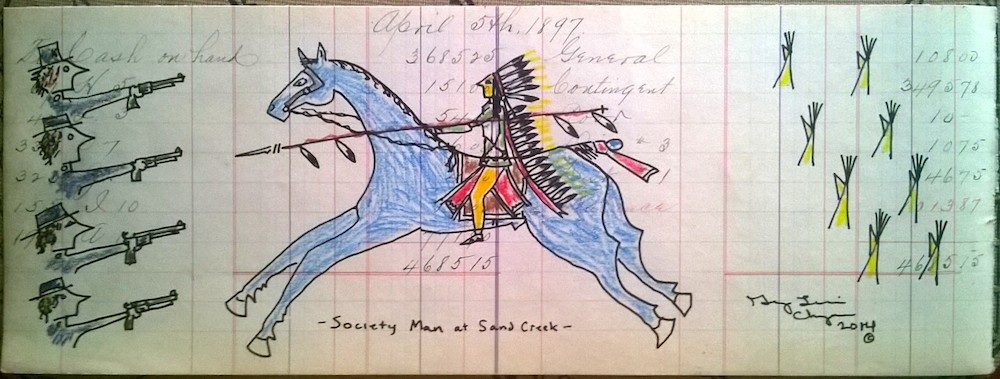

Brent Learned is an award-winning and collected Native American artist who was born and reared in Oklahoma City. He is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. Brent graduated from the University of Kansas with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts. He is an artist who draws, paints, and sculpts the Native American Indian in a rustic, impressionistic style. He has always appreciated the heritage and culture of the American Plains Indian. He tries to create artwork to capture the essence of the American Plains Indian way of life with accuracy and historical authenticity. Although Brent has many different styles, he is typically known for his use of bold, vibrant colors in his depictions of the American Plains Indian. Brent’s work resides in museums such as the Smithsonian Institute-National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., the Cheyenne/Arapaho Museum in Clinton, Oklahoma, the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, and the University of Kansas Art Museum in Lawrence. He has work in private collections such as the Governor of Oklahoma Private Collection, the governor’s mansion in Oklahoma City, the Haskell Indian University in Lawrence, Kansas, and the Kerr Foundation Private Collection in Oklahoma City. Brent also has the honor of having one of his paintings displayed in the Democratic National Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

George Levi is Cheyenne and Arapaho. Husband, father, Kit Fox Society member. Sand Creek descendent. He is also an artist specializing in ledger art, acrylics, and watercolors. His art has been exhibited at the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institute and the Denver Art Museum, among other places.

Margaret Noodin received an MFA in creative writing and a PhD in English and linguistics from the University of Minnesota. She is currently an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where she also serves at the director of the Electa Quinney Institute for American Indian Education. She is the author of Bawaajimo: A Dialect of Dreams in Anishinaabe Language and Literature and Weweni, a collection of bilingual poems in Ojibwe and English. She is a member of Miskwaasining Nagamojig (the Swamp Singers) a women’s hand drum group whose lyrics are all in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe). To see and hear current projects visit www.ojibwe.net, where she and other students and speakers of Ojibwe have created a space for language to be shared by academics and the Native community.

Sara Marie Ortiz is a twenty-eight-year-old Acoma Pueblo memoirist, poet, scholar, aspiring filmmaker, youth trainer, and Indigenous Peoples advocate. Her work has been widely published and garnered numerous awards, among these the Truman Capote Literary Fellowship, the Native American Literature Symposium Morning Star Award, and an American Indian Graduate Center Fellowship. Her book of experimental poetry, Red Milk, was released in 2013. She is the proud daughter of Simon Ortiz.

Simon J. Ortiz, Acoma Pueblo, author-writer-editor of more than 25 books of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and children’s literature, Regents Professor of English and American Indian Studies at Arizona State University. Honors: 2 NEA awards (1970 and 1980); Lifetime Achievement Award from Returning the Gift—Native North American Writers (1993); Lifetime Achievement Award, Western States Arts Federation (1999); Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Writers Award (1996-1998); Lannan Foundation, Artist Residency Award (2000); New Mexico Humanities Award (1985), Golden Tibetan Antelope Prize for International Poetry, Qinghai, China (2013). Ortiz is father of three grown children and grandfather of nine beautiful grandkids.

Billy J. Stratton currently teaches contemporary Native American/American literature and film in the Department of English at the University of Denver. His scholarly and creative writings have been included in numerous books and journals. His monograph on the development of the Indian captivity narrative genre, Mary Rowlandson and King Philip’s War, titled, Buried in Shades of Night, was published in 2014. His latest project is an edited collection that addresses the fiction of Stephen Graham Jones.

Frances Washburn was born and raised on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. She earned her PhD from the University of New Mexico and was a visiting professor at the University of Nebraska before coming to the University of Arizona, where she is currently an associate professor in the American Indian Studies Program and the Department of English. She is the mother of two children, Lee and Stella. Her first novel, Elsie’s Business, was published is 2006, and a second novel, The Sacred White Turkey, came out in 2010. Her latest novel, The Red Bird All-Indian Traveling Band, was published by the University of Arizona Press as part of its renowned Sun Tracks series in 2014. She also recently completed a biography of Louise Erdrich for Praeger Press (2013). In addition to fiction, she has published scholarly articles and poetry in a variety of venues such as Wíčazo Ša Review, Weber, and Denver Quarterly.

Michael Wasson’s poems appear in American Poets, Prairie Schooner, and DIALOGIST, among others. He is Nimíipuu from the Nez Perce Reservation and lives in rural Japan.