War of Words

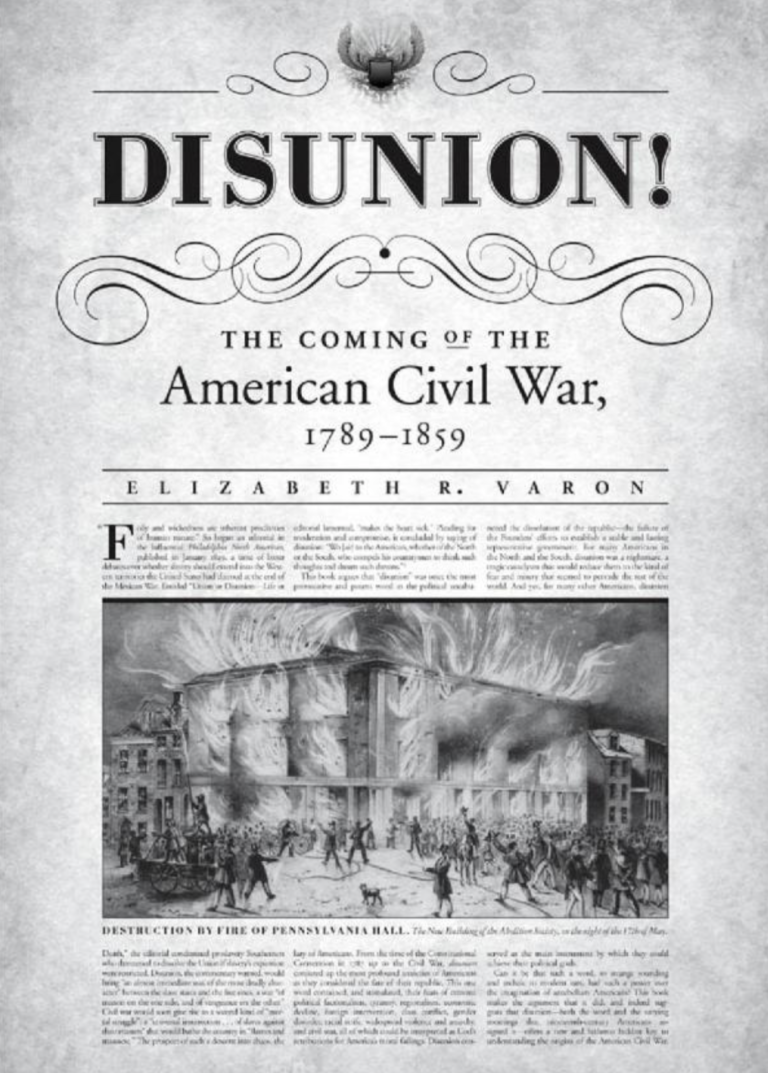

Among many new syntheses of the decades preceding the Civil War, Elizabeth Varon’s Disunion!: The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859 is one of the most insightful, innovative, and readable. Interweaving recent scholarship on race, gender, and popular culture with traditional political history, Disunion! provides both a valuable synthesis and a compelling argument about the political significance of language. At a glance, her conclusion that “disunion” rhetoric proliferated and evolved over the decades preceding the Civil War seems obvious. But Varon has much to add about the power and breadth of this word. The tendency to conflate “disunion” with “secession,” Varon suggests, is the primary culprit for our lack of attention to disunion discourse. “Secession” was the formal policy act of withdrawal from the Union. “Disunion” was far more capacious.

Varon clarifies these two terms and provides a useful taxonomy of disunion rhetoric. From 1789 through 1859 the word appeared primarily in five “distinct but overlapping” registers that together made the idea of disunion central to political conflict over slavery’s fate in (or outside of) the American republic. Disunion as a “prophecy” warned of “national ruin” if slavery was allowed to become divisive. Politicians, especially Southerners, frequently used disunion as a “threat” to extract concessions. Moderates employed disunion as an “accusation of treasonous plotting” to besmirch political adversaries, especially abolitionists and Southern fire-eaters. Over time, disunion rhetoric came to describe a “process of sectional alienation” whereby the free North and slave South became increasingly incompatible. Finally, some extremists in both sections, and by the late 1850s many Southern political leaders, advocated disunion as an actual policy “program for regional independence” (5).

Varon shows how slavery magnified popular forebodings over internal and external threats to a republic’s survival. For prophets of disunion, fears about sectional division over slavery came to encapsulate the many perils of disunion, including foreign invasion, popular uprising, economic collapse, race war, and disruption of traditional social, especially gender, hierarchies. Already in the Constitutional Convention, disunion threats surfaced as a Southern tactic for securing protections for slavery, but the compromises of the Constitution seemed to obviate further conflict and establish a strong, durable union. Disunion rhetoric as both an accusation and a threat, however, flourished as a partisan device for Federalists and Jeffersonians arguing over Alexander Hamilton’s economic program, Federalist foreign policy, Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase and 1807 embargo, the War of 1812, and, on an early occasion, over slavery in a spirited 1790 House debate incited by Philadelphia Quakers’ petitions against the African slave trade.

Northern congressional attempts to eliminate slavery in Missouri raised the stakes of disunion rhetoric and made its sectional undertones explicit. Yet, even in the Missouri crisis (1819-1821), disunion rhetoric remained “a kind of political gamesmanship or parliamentary maneuvering.” Neither slavery extensionists nor restrictionists in the early republic intended disunion “as a process or program.” By invoking disunion so often, though, participants on both sides of the Missouri debate further ensconced the term in the national political lexicon. Additionally, “the Missouri controversy racialized the discourse of disunion by adding lurid word pictures of ‘servile war’ to the ‘language of terrifying prophecy,'” especially in light of the black revolution in Haiti and Gabriel’s abortive rebellion in Virginia in 1800 (44-45). Meanwhile, burgeoning free-black communities in the North propagated a new theory that only emancipation and racial equality could ensure perpetuity of the Union.

By organizing political history around a rhetorical concept, Varon makes new space for the politically marginalized. By showing that slavery’s politicization hinged on popular discourse as much as on votes cast and decisions rendered, Varon enables us to see how those excluded from conventional policymaking still profoundly influenced national politics. Famous black radicals like Nat Turner, David Walker, and Frederick Douglass powerfully shaped the debate over disunion. More to the point though, Varon shows that countless enslaved and free blacks heightened sectional tensions by challenging proslavery authority, not least by fleeing slavery and protecting fugitive slaves in their communities. Varon also elucidates how women antislavery activists’ disregard for antebellum gender conventions intensified sectional alienation by convincing Southerners (and conservative Northerners) that abolitionists aimed to revolutionize the American social order.

The emergence of immediatist abolitionism in the 1830s transformed the discourse of disunion. Familiar disunion language suffused the rabid, widespread anti-abolitionist responses to the growing radical movement. The new abolitionist challenge, embodied in the postal propaganda campaign of 1835 and subsequent congressional petition drives, inspired new arguments about slavery as a “positive good.” Furthermore, already in the initial 1836 debates over a prospective House gag on antislavery petitions, proslavery extremists like South Carolina’s James Henry Hammond invoked disunion as a process well underway. Abolitionists retorted that slavery was the “root danger” to the Union and dismissed Southern disunionism as “empty bluster” (122).

Over the next few years, abolitionists developed two comprehensive responses to proslavery disunionism, both of which reinforced Southern anxieties about protecting slavery in a half-free republic. One was William Lloyd Garrison’s espousal of an antislavery disunion philosophy, which argued that the Union was fundamentally corrupted by slavery and that conscientious Northerners could no longer bear the moral burden of participation (152-154). The much larger group of (male) abolitionists who joined the Liberty Party and later the more moderate Free Soil Party devised the Slave Power Conspiracy argument. Political abolitionists established their commitment to the Union by smearing the Slave Power—the proslavery politicians that controlled the federal government and infringed on Northern liberties—as the real menace to national unity. Varon seems to argue that Garrisonians did more to contribute to polarization over the fate of the Union than the political abolitionists who decried the Slave Power. Perhaps, but political abolitionists played an indispensable role in inciting the aggressive Southern political responses that so escalated sectional conflict, precisely because Southerners deeply feared their efforts to channel abolitionism into concrete antislavery policy. Through those battles the Slave Power argument gained currency across the Northern electorate, making compromise on slavery, and especially its westward extension, an ever thornier project.

The midcentury sectional crisis over slavery in California and New Mexico and the Compromise of 1850 constitute a crucial pivot in Varon’s history of disunion discourse. Never before this crisis had support for disunion as a program been so pervasive. The compromise’s apparent success at mollifying friction between Northern and Southern moderates only further inflamed radicals on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act corroborated abolitionist charges of Northern complicity in the slave system and soon generated unprecedented “northern outrage” (235). Black resistance in the urban North to the odious law especially disturbed slavery’s champions. These Northern responses in turn “legitimized a long-standing argument of the South’s proslavery vanguard—that Northerners could not be trusted to keep their promise” (235). Southern politicians demanded renewed assurances that the federal government would protect slavery, but their new affronts—the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott decision, insistence on the fraudulent proslavery Lecompton Constitution for Kansas, and calls for reopening the African slave trade—gave further credence to antislavery charges that a Slave Power Conspiracy was propelling the nation toward disunion.

The Republican Party that coalesced across the North in response to these aggressions strove to prove its unionism at the moment when Southern secessionists were growing boldest. As “disunion threats materialized into a regional program, and as images of revolution and invasion swirled in the political atmosphere,” Republicans grew increasingly antagonistic towards Southern ultimatums, as famously demonstrated in William Seward’s “irrepressible conflict” speech (320). These tensions crystallized in the aftermath of John Brown’s insurrectionary raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Brown’s invasion and the sympathetic Northern reaction elicited by his antislavery martyrdom terrified Southerners across the political spectrum and, for many, made disunion seem unavoidable.

Brown’s 1859 raid rather than the outbreak of the Civil War seems a curious choice of denouement (notwithstanding a brief epilogue on secession and the war years). It was likely dictated by the editors of the Littlefield History of the Civil War Era series, which will include a separate book on the secession crisis from 1859 through 1861. A more complete discussion of the actual mechanics by which disunion became secession (through different trajectories in various Southern regions) would have better completed Varon’s narrative and further strengthened her important point about the complicated relationship between “disunion” and “secession.”

Varon impressively brings together social, cultural, and of course political strands in a very manageable volume. (By contrast, recent prize-winning syntheses of this period by Sean Wilentz and Daniel Walker Howe are twice the length of Disunion!.) In trying to incorporate all the key highlights from conventional political histories of the period as well as new insights about the antislavery movement, Varon’s chronological narrative occasionally strays from its focus on the power of “disunion” rhetoric but never for too long. By delivering her arguments through an accessible narrative framework, though, Varon has crafted a synthesis that speaks to specialists and remains approachable for undergraduates, scholars in other fields, and general readers. In the process, Varon offers fresh and enlightening conclusions about the power of “disunion” in the seven decades before the war of words over slavery became a war of arms over union.