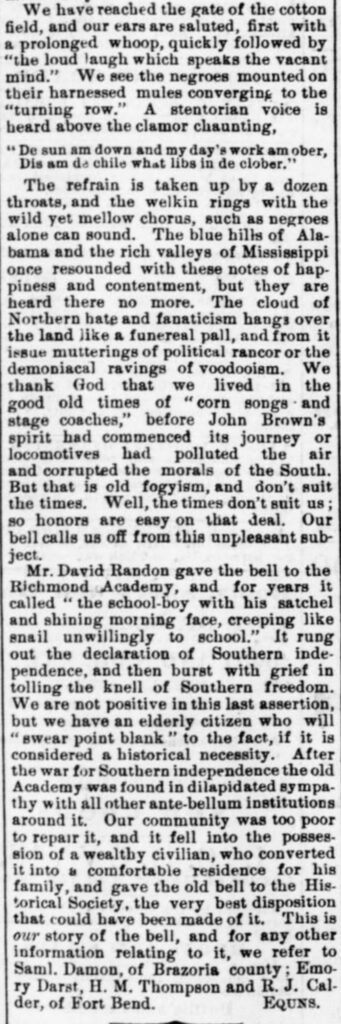

Missing lecture transcripts: Over the course of the 19th century, popular American authors often delivered speeches on the lecture circuits of their day—primarily in lyceums, library associations, local clubs, and subscription-based societies—as a way of engaging the public and securing supplemental income. Some lectures were reprinted or carefully transcribed (see Emerson’s, for example). Others were not. Nevertheless, missing lecture transcriptions may still exist in archived or digitized newspapers from the period. Twain, for example, lectured on Hawaii (then called the Sandwich Islands) after returning from an assignment there in 1866. In all, he delivered fifteen or sixteen such speeches, primarily in Grass Valley, California, and Nevada City, Nevada. Other than their general subject matter, these lectures are considered entirely lost. In his book on the subject, Walter Francis Frear not only assumes that the lecture notes were destroyed by the author, but also considers attempts at their reconstruction to be futile, since “the more or less scanty newspaper accounts necessarily lack much in diction and manner of presentation by the lecturer” (177, 184). Nevertheless, it may be possible to locate more complete descriptions (if not transcripts) of these lectures in digitized newspaper archives. Other authors have similarly incomplete lecture corpuses, including Frederick Douglass, Herman Melville, Henry Ward Beecher, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Douglass’s and Beecher’s numerous lectures and sermons have been scrupulously catalogued, but they gave so many during their lifetimes that their lecture bibliographies are almost certainly incomplete. Gilman’s situation is practically the inverse: scholar Carol Farley Kessler notes that though Gilman “delivered so many lectures on ethics, economics, and sociology that she . . . lost count” (97), less than one hundred notices of her lectures have been found in print.

Further Reading

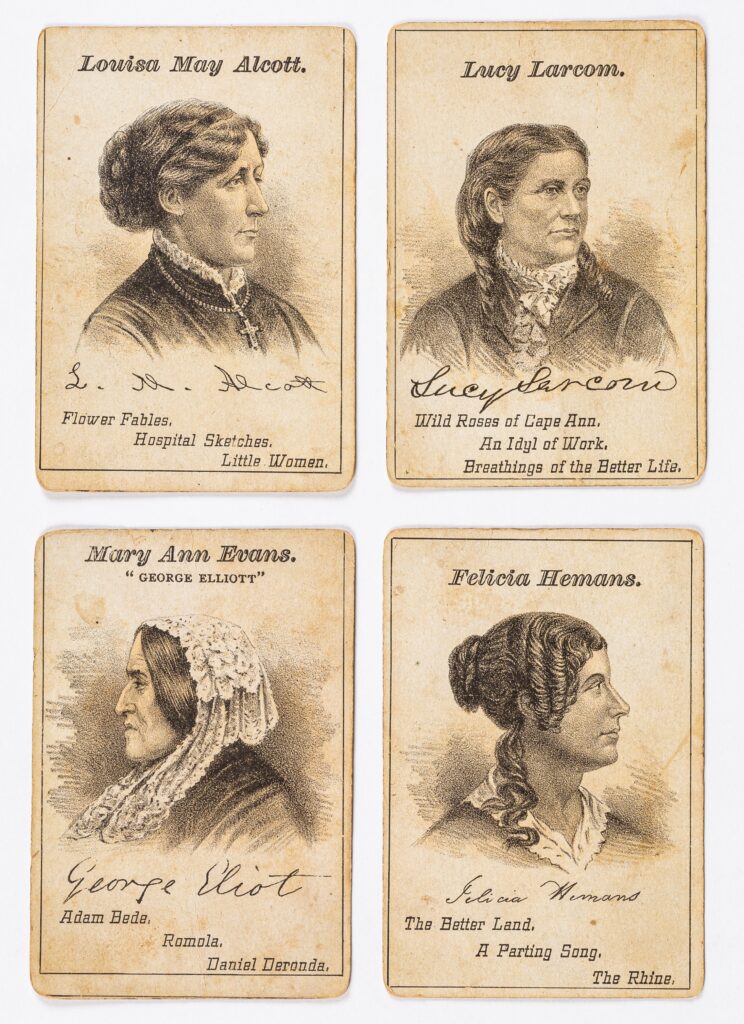

Louisa May Alcott, The Journals of Louisa May Alcott. Edited by Joel Myerson, Daniel Shealy, and Madeleine B. Sterne (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997).

Francis Bacon, The New Organon, ed. Lisa Jardine and Michael Silverthorne (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

P. T. Barnum, The Humbugs of the World (New York: Carleton Publisher, 1866).

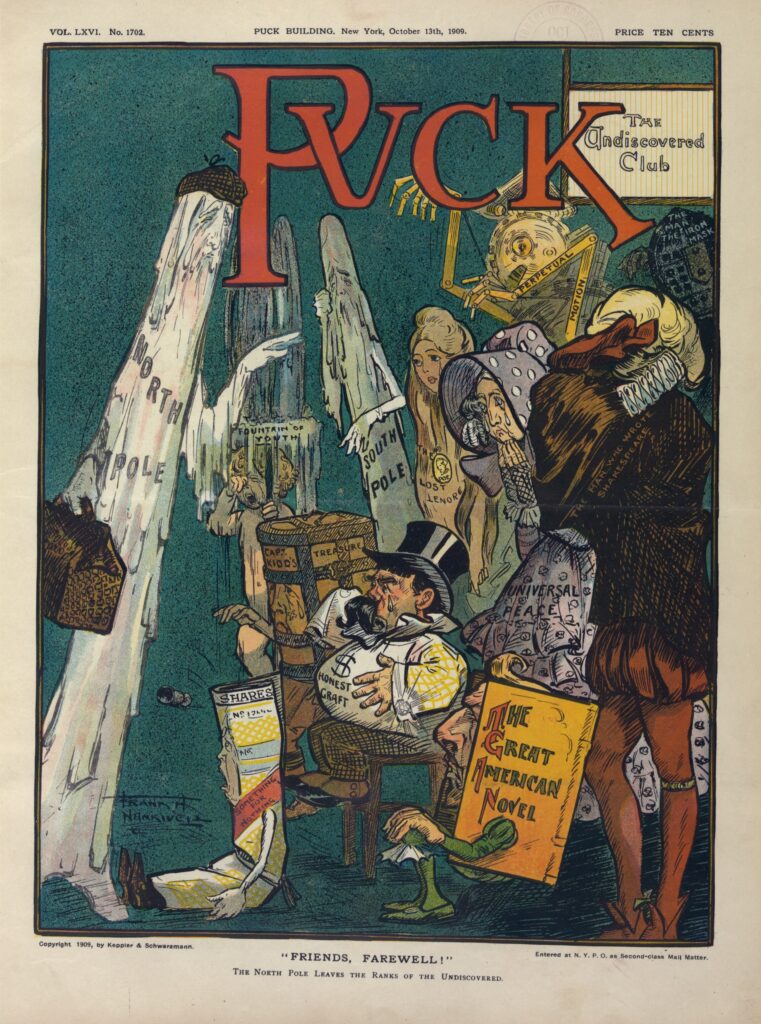

Lawrence Buell, The Dream of the Great American Novel (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2014).

Hannah Crafts, The Bondwoman’s Narrative, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. (New York: Time-Warner Books, 2002).

Karen Dandurand, “Another Dickinson Poem Published in her Lifetime,” American Literature 54 (no. 3, 1982): 434-37.

Karen Dandurand, “New Dickinson Civil War Publications,” American Literature 55 (no. 1, 1984), 17-27.

Karen Dandurand, “Publication of Dickinson’s Poems in Her Lifetime,” Legacy 1 (no. 1, 1984), 7.

[John William de Forest,] “The Great American Novel,” The Nation 6 (no. 132, January 9, 1868): 28.

Brigitte Fielder, “Nineteenth-Century African American Literature Recommendations,” The Dickens Project, UC Santa Cruz, August 6, 2022, https://dickens.ucsc.edu/news-events/news/afam-lit-recommendations.html .

Walter Francis Frear, Mark Twain and Hawaii (Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1947).

Caroline Gebhard, Katherine Adams, and Sandra A. Zagarell, “Recovered from the Archive: Two Stories by Alice Dunbar-Nelson,” Legacy, 33 (no. 2, 2016): 404-7.

Julian Hawthorne, Nathaniel Hawthorne and His Wife, A Biography, 2 vols. (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1884).

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Letters, vol. 15, ed. William Charvat, et al. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989).

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Selected Letters of Nathaniel Hawthorne, ed. Joel Myerson (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2002).

Merle Johnson, A Bibliography of the Work of Mark Twain, Samuel Langhorne Clemens (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1910).

Carol Farley Kessler, “Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1860-1935,” Modern American Women Writers ed. Elaine Showalter, Lea Baechler, and A. Walton Litz (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993).

Herman Melville, Correspondence, ed. Lynn Horth (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1993).

Johanna Ortner, “Lost No More: Recovering Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Forest Leaves,” Commonplace 15 (no. 4, Summer 2015).

Hershel Parker, “Herman Melville’s The Isle of the Cross: A Survey and a Chronology,” American Literature 62 (no. 1, 1990): 1-16.

Basem L. Ra’ad, “‘The Encantadas’ and ‘The Isle of the Cross’: Melvillean Dubieties, 1853-54.” American Literature 63 (no. 2, 1991): 316-23.

Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (New York: Macmillan, 2010).

Bonnie James Shaker and Angela Gianoglio Pettitt, “‘Her First Party’ as Her Last Story: Recovering Kate Chopin’s Fiction,” Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers 30 (no. 2, 2013): 384-96.

Zachary Turpin, “Searching for Proud Antoinette: Evidence and Prospects for Whitman’s Phantom Novel,” WWQR 37 (no. ¾, Winter/Spring 2020): 225-47.

William White, “Whitman’s First ‘Literary’ Letter,” American Literature 35 (no. 1, March 1963): 83-5.

Walt Whitman, The Early Poems and the Fiction, ed. Thomas L. Brasher (New York: New York University Press, 1963).

Walt Whitman, Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, ed. Zachary Turpin (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2017).

Walt Whitman, Prose Works 1892, vol. 1, ed. Floyd Stovall (New York: New York University Press, 1962).

“Wild Frank’s Return,” Story of the Week, Library of America, October 18, 2013, http://storyoftheweek.loa.org/2013/10/wild-franks-return.html .

Harriet E. Wilson, Our Nig, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Richard J. Ellis (New York: Vintage Books, 2011).

This article originally appeared in October 2023.

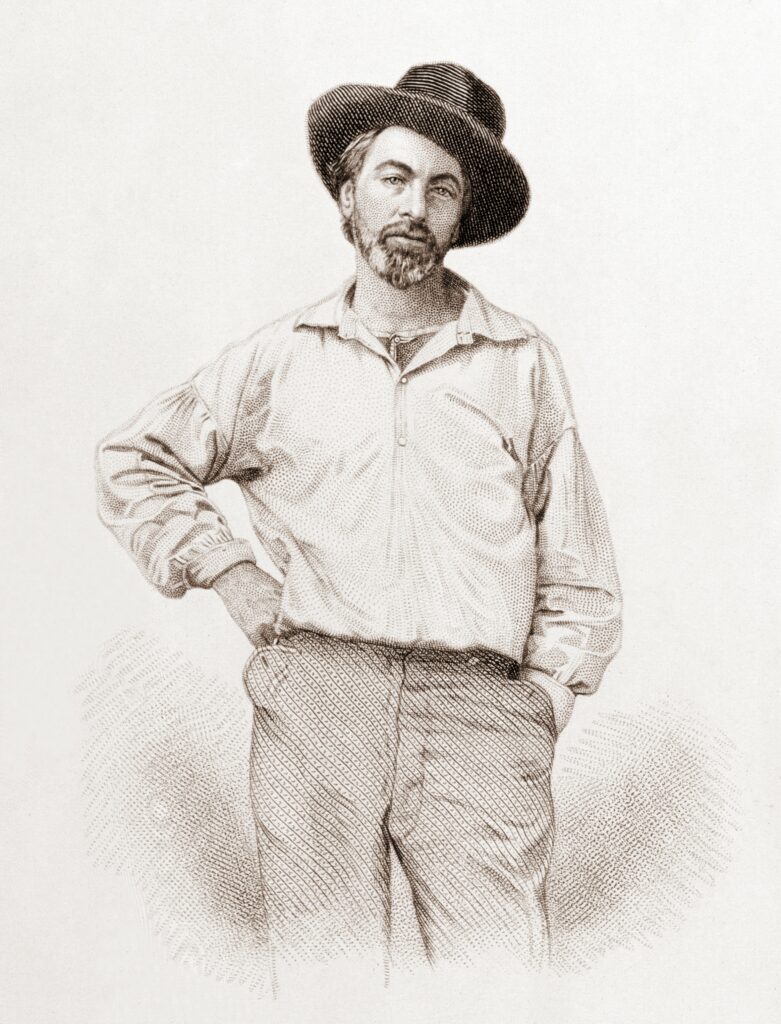

Zachary Turpin is an Associate Professor of American Literature at the University of Idaho, a former Kluge Fellow at the Library of Congress, and a former Peterson Fellow at the American Antiquarian Society. A scholar of nineteenth-century American periodical culture, as well as physical and digital archival research methods, he specializes in recovering the lost writings of nineteenth-century authors, including major works by Walt Whitman, Emma Lazarus, and Rebecca Harding Davis. His writings have appeared inJ19, ESQ, the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, PMLA, and elsewhere.