Poems

Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet)

I had been twice to Pond

before I learned you had

not only been there, but filmed it.

Of course I felt stupid, losing

the trail so clearly marked.

Each time we went, all hundred

of us plus the Russian crew, some

older one who saw the steep climb

from the beach, the long dirt road

to the store and cultural center

became visibly daunted and then

was offered a ride on a four-wheeler

by a passing elder.

Each time drugs were offered

by teenagers on the co-op steps

(coop, I kept seeing). I want to kill myself.

One of the black poems inked

on the porch rail. Once,

a whale (narwhale, beluga) rolled

in the tideline chip. Just spine

and gristle, but the rope

that tied it a brilliant yellow

and its lungs the lapis of Keats.

After throat singing and Arctic

games, I bought a copy

of your film. It is on the shelf

by my desk, still wrapped

two years later. There are

so many reasons I am

afraid to watch it.

On Beechy

The stones on the graves, like all the other stones, are fossils:

corals and crynoids from the old seas of an old climate. There is a lot to say

about Franklin, the man who ate his boots and whose grave

is not among these, is not yet known. And Lady Franklin,

who made sure his ghost was chased across the Arctic, his name

hove into news. On the point above Somerset House,

built and stocked should he return, ruining in Arctic time,

my favorite cairn: rocks topped by a steel plaque, metal etched

with a man in thick-framed glasses. Caricature of a scientist

from a time even stranger than Franklin’s, another lapsarian age.

Iron hoops that once ringed barrels of food and fuel

decorate the shore, circle stones. A ship’s mast points out

toward where they might have gone: horizon, heaven, hell.

We wander. We avoid what’s forbidden. We wonder

what’s in the brass tubes laid out like kindling. Someone

keeps watch for bears. Someone talks about history.

I pry a fossil from frozen mud. I don’t want to leave

anything of myself, but to take a mnemonic of what I’ve marked,

marred? That tribute feels right.

Thinking of Places I Have Begun to Know

Yearn, yearn

what bloom has gone

to paper now, brown?

What bulbil ready

on which stalk?

Campion, gather

your snow drift

Your loess-blanket

Which bay is iced?

Which glacier slows?

Leaves here, south burnish

Then an odd warmth

& grass sprouts

Which lead? Which polynya

What hunt now

at Pond, at Clyde?

What, shot, drapes

the snow-go,

the towed sledge?

Oh my holiday knowledge

My Augusts Deep

in years but not broadened

to seasons I try

to picture it Caribou

over the tracks of caribou

left last year that

I walked Fox white

Ducks gone And what remains

and so belongs

Things I think you’d hate about Provincetown in 2008

Portuguese families cashed out and moved to Truro.

Apples, chokecherries, peach plums, rose hips, blueberries ungathered. Fallen.

Not so sure about whale watching—you may have even liked it.

Condos on the edge of the quaking bog.

That so little’s changed (taffy, kites, summer’s ephemera).

That town hall still stands but this year’s town meeting will be in the basement of the high school annex, hall condemned and funds for repair uncertain.

Fast ferries.

Unsure about the old museum with its ½-scale model of the Rose Dorothea repurposed as the library; the old library a real estate office.

(Where did the art, the horse-drawn fire truck, the model of Harry Kemp’s dune shack go?)

Drag queens balanced on segues.

You’d love the West End Racing Club—Flyer in his eighties still teaching the kids to swim and sail, still terrifying in his blustered love.

Wired Puppy—fancy coffee sipped while blogging.

Maybe Ellie, who each night sings in the town square, linebacker shoulders, short skirt, heels.

My slant attention and squint questions.

Maybe me—childless (you were, too), paired to a woman twelve years older than me (thirty years between you and Miriam), calling this place home and yet so often afield (your ship not even housed here, but halfway north, in Maine).

Statement of poetic research

In the Wake of:

MacMillan Pier:

I’d worked on boats that docked there for years before thinking to ask who it was named for.

On the Display at the Museum:

Stuffed polar bears? A kayak? What did they have to do with this place, with what the town’s landmark tower was built to commemorate: the landing of the pilgrims?

Discovery:

Maybe it was Flyer (or Dan?) who told me about MacMillan. It started to come together. I was leaving Alaska, half returning. I was done with the manuscript of poems about explorers and ice. I was moving to California for a fellowship and my love was moving back to Cape Cod. How are distances bridged? How do you return to a place that once was home? I looked for role models I could fight with. Hello, Donald B. MacMillan.

Sleuthing:

I read all of Mac’s books. Hunted down his old National Geographic articles. Got into the museum archives to read his cranky letters about the proper management of collections. Tried to get to Bowdoin to visit the Peary/MacMillan museum (just a drive away but for some reason still unseen). Found a goal: go north.

A Plan is Hatched:

I pulled strings. I schemed. I got work on a boat in the Eastern Canadian Arctic.

Getting Hooked:

More than I ever expected, the landscape and history resonated. Deeply. There is nothing like the world above treeline–small flowers huddling together to create enough warmth to bloom, seasonally thawed ground soft/hard/rolling/mushy underfoot, horizon. And to come upon rings of lichen-covered stones that, centuries ago and then just decades ago, held down skin tents? Ancient foundations with old copper kettles and monofilament fishing line? To feel miles and hours and moods of looking suddenly collapse to a single, hot point: Bear. Musk ox. Walrus.

I am a slow writer. I know this now. A late bloomer. A deliberator. I hide under a rock and try and be the rock. Quiet. Spying can you teach a lot. I spy on myself. I try not to get caught. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle applies: the observer changes that which is observed. Observing changes what is observed.

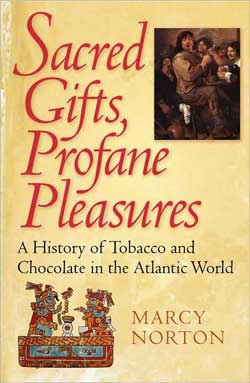

After writing the poems of my second book, Approaching Ice, which investigated the romance of polar exploration as an armchair traveler, I wanted to write into the high latitudes differently. Living in Alaska made the Arctic less theoretical. More familiar and also more complex. It was no longer distance and discovery that moved me, but the concept of a storied land. A land beautiful and inhabited for millennia.

I wanted to be culpable, to find a way to look at place more deeply and with more at stake personally. The idea of investigating place through a conversation between two people (myself and MacMillan), two places (Provincetown, the Arctic), and two times and all the awarenesses of each (his, mine) began to develop. It would be an intimate dance, a wrestling match of cultures, a frustrated love song.

The fact that all our lives, here and there, are being affected by climate change and other human-sourced impacts was part of the draw. Cape Cod is low-lying and sandy. Sea level rise is on the minds of insurance underwriters. The Arctic is a place on the globe where temperatures are warming more than elsewhere. The most toxic lake in the world is on a remote island north of Norway–airborne mercury and organo-pollutants fall out across the north. What will happen when all the methane stored in permafrost is released? What will happen when ice no longer covers and so reflects light back from the ocean’s surface?

How does a poet write about highly politicized issues in a way that is integrated with both nature and culture? In a way that is seductive? In a way that isn’t didactic?

Donald B. MacMillan made thirty voyages to the Arctic. He almost went along with Peary when Peary made his dash for the pole. And he was born in Provincetown. A place with deep meaning for me. I was not born on Cape Cod. I wasn’t even born on the East Coast, but I came of age there, in a way. I moved east for love, stayed, and fell in love with the place, too.

What drew me to Provincetown was both its physical beauty and its culture. I even liked its tacky fringe. There were boats, artists, oddballs, writers, and secrets, which for me is an ideal mix. Queerness is the norm (although there a conservative countermelody can be heard on the wharf, in the schools, tossed from rolled-down windows of cars stopped in traffic), which allowed me to live without needing to consider sexuality, to defend it or figure out how it might or might not define me against. I can’t say strongly enough what a freedom this was and is.

MacMillan didn’t spend his whole youth in Provincetown. His father died in a fishing accident, leaving his mother to raise him. She couldn’t quite manage, so he left to live with relatives in Maine. As an adult, he returned. He married a woman thirty years his junior who, when she was growing up, “played MacMillan.” I haven’t yet figured out how to wrestle with that strangeness.

Mac, as people called him, built a schooner, the Bowdoin, and took it north. He brought Miriam. He brought color film. He brought boys in a floating classroom. He died near the time that I was born. We didn’t quite overlap, but it was close. I am not a continuation of him, and yet

I don’t know how the story will end, how the book these poems begin will shape its arc. I’m trying to hold off a bit. Next summer, I’m scheduled to work again in the Arctic, and for the first time part of the trip will be in Greenland. Mac spent a lot of time up there. How my trip will shape the way I see him and his trips, how I see the Arctic itself, how I interpret his interpretations of the land and people, is a blank on the map.

Meanwhile, things accrue. Home, I walk by Mac’s old house every once in a while. The broken antler on the strange orange elk mounted over the front door dangles for the fourth year, still not broken off. Would Mac have fixed it? Or would he not have noticed, too busy living again, from home, his time away?

I’m going to try and convince the owners to let me go through the house. Or maybe sit on the porch. Look out over what has changed, what hasn’t. Try and figure out how to celebrate, castigate, laugh and mourn at once.

Further Reading

Biographies of MacMillan range from the young-adult-appropriate Captain Mac: The Life of Donald Baxter MacMillan, Arctic Explorer, by Mary Morton Cowan (Honesdale, Pa., 2010) to Everett S. Allen’s hero-worship-esque Arctic Odyssey: The Life of Rear Admiral Donald B. MacMillan published by Dodd, Mead and Company (New York, 1962)–note the suspicious overlap of publishers between Allen and Miriam MacMillan. Miriam MacMillan, whom Donald married at age 60, wrote a fair amount for the general public, and one can sense the hand of Mac behind them: Etuk: The Eskimo Hunter, Dodd, Mead and Company (New York, 1950), Green Seas and White Ice: Far North with Captain Mac, Dodd, Mead and Company (New York, 1948). I had high hopes for juicy tidbits in Miriam’s I Married An Explorer (London, 1952), but alas. Samples of MacMillan’s own voice can be found in his two full-length autobiographical accounts of his explorations, both written fairly early in his career: Four Years in the White North (New York, 1918) and Etah and Beyond, or, Life Within Twelve Degrees of the Pole(Boston, 1927). I do wish he’d done more writing in his later years. Kah’da: Life of a North Greenland Eskimo Boy (New York, 1930) is a more romantic/fictionalized view of the North by MacMillan. Mac’s articles in National Geographic are also rich. One of my favorite moments is his explanation of why the musk ox rubs its hoof to its eye.