Fires in the Hearth

My Great Great Grandparents Read

George Moses Horton and David Walker

Northampton County, North Carolina 1852

I

“My heart to lift…”

—from George Moses Horton’s “Myself”

To see her carrying tomatoes

up the low path round the side

of the rose bushes, hair tied back,

might a man take a break, sit down

in the miracle of his eyes to see

how it feels to have a woman open

him up wider than he thought

wide could ever be, and sing

to what lays up inside tomorrow,

that kind of being free, that timber

in this land where woe will give way

someday. The horse’s leg in his lap,

he knows a hoof is softer than stone,

but taps ground to make the sound

of a dream sitting on top a wish,

the high place where things begin.

II

To walk out into a world,

to hear a bird’s wing sing

riddles of masks and clouds,

a man must trust a city

with his weak assembly,

the beating of his joints

into where they make whole

a pile of bones and wishes,

a body or a ship sailing

in dreams that cannot name

themselves, moving the night

aside to where he can trade

the business of making chains

for the wild fears of love.

III

At night his hammer found

its way to her across the heads

of cabbage around back, sounds

soft, then hard, then nothing,

a message she thought went up

to a star he must have known

from where he went sometimes,

slipping out of sight inside

the carriage house, invisible

in between the big clock

that banged in the mansion,

some power, she thought, not

his but what belongs to What

made us flesh with air to breathe.

IV

Wrapped into his eyes,

she listens until his voice

is sucked into the calm,

a lace let down easy over all

the field, him making words

sing off the pages, correcting

him when he falters, a teacher

to the man she loves, the poet

they read held in a heaviness

of chains from the black metal

of law in Northampton, black

skin every shade of what

can be seen, what can be sung.

V

“…troubling the pages of historians…”

from David Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles; Together

with a Preamble, to the Colored Citizens of the World

It was done when the leaves

shut up the clatter of wind against them,

the last hound ripping the peace

until the candle shivered, blood

giving way to the child’s first cry,

Walter holding Walker’s Appeal

in his hand, the midwife wiping

sweat from Mary’s forehead,

calling God Allah, their son Ruffin,

a name born in wishes, a name

to travel for a hundred years

to the spirits of poets in an Irish town,

Baltimore, where their songs are

the music of the corner, the corner

an altar to a people’s will to love.

Poetic Research Statement

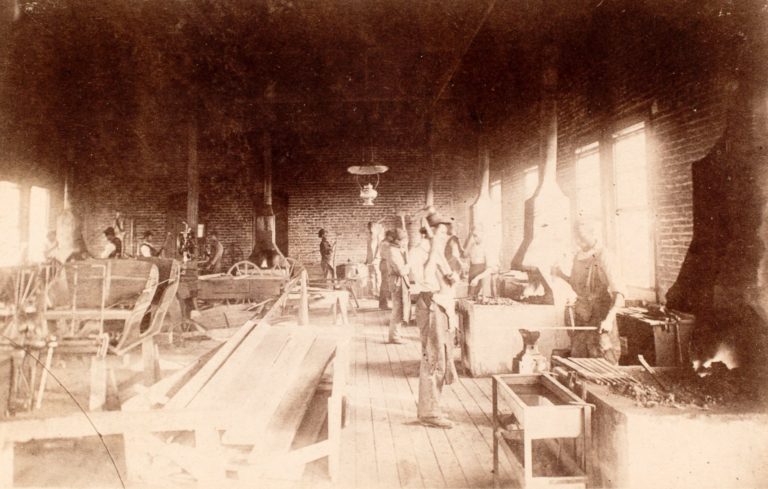

In Courtship and Love Among the Enslaved in North Carolina, Rebecca J. Fraser notes that North Carolina was the only place on the North American mainland where the West Indian and Caribbean John Kooner parades took place. Black folk took on clothing resembling traditional West African dress and had mock performances where they overturned the southern hierarchy, acting out scenes subverting the status enforced in the day to day operations of plantation life. When I came upon this information, I was reflecting on my completed poem “My Great Great Grandparents Read/ George Moses Horton and David Walker,” and I felt affirmed. I have no way of knowing the actual facts of the romantic life of my paternal great-great-grandparents. Such is the tragedy of slavery. What I do have is a faith in the ability of black people to maintain loving structures despite the pressures of slavery.

The opportunity to write a poem rooted in research for Common-Place was an opportunity to continue a writing method that began forty-three years earlier, when in 1974 I sat with elders and listened to oral histories of how things came to be. In 1994, along with my father and one of my sisters I drove from Baltimore down to Northampton County, North Carolina, to visit my Aunt Janet, my father’s oldest sister. We took her to Shoney’s, a buffet restaurant. She was a small woman, about the same size as her mother, Grandma Mariah. They shared a mysterious stillness in their being, an air that commanded our attention. So I was immediately entranced when Aunt Janet declared, “Michael, I have something to tell you.” In the world of my grandparents and great-grandparents, the elders often passed vital information to the oldest children, and there I was in that part of the country where my family traces its origins. My mother’s side of the family traces back to this same piece of land stretching across the state line from North Carolina into Virginia, just seventy-five miles west of the Dismal Swamp, where black folk escaped from slavery and took the perilous journey into the swamp to set up a community. So I leaned forward to listen as Aunt Janet told the story of her father’s parents, my great-grandparents.

She told us of two little sisters who were kidnapped as children in West Africa and taken to the coast, where they were separated and placed on two different ships, never to see each other again. The one whose name was Phoebe survived the voyage to the western hemisphere and landed in the U.S., where she married a Native American. In 1852, they had a daughter whom they named Elvira. When Elvira became an adult, she married a man by the name of Ruffin Weaver, and they had several children, including my grandfather, Joseph Lundy Weaver, who inherited his mother’s height. The oral history of Elvira and Ruffin was well known to us as a family, and I was able to verify the facts in census reports, and records of birth, death, and marriage that I found on ancestry.com. Phoebe’s parents are listed as “unknown,” identities lost in the grief of the Middle Passage or Maafa, the African Holocaust.

Aunt Janet passed away, and I held onto the story for years, checking now and then with relatives to see if any of them had heard the story of Phoebe. It seemed my Aunt Janet had passed on to me something of a family jewel, the story of this little girl who survived the trip across the Atlantic and became a matriarch of the Weaver clan. The best clue I had as to why the story was so little known was in what my Uncle Andrew, the youngest of the twelve siblings, explained to me. He said the elders often gave such information only to the eldest sibling, so Aunt Janet was keeping a tradition.

Almost two decades later, I had a chance to make good use of the way Phoebe inspired me. In 2012, I was asked by politically conservative friends in Wisconsin to write a book of poems about African American history, and I chose to write a series of thirteen poems entitled A Hard Summation to illustrate significant themes in this history, with a focus on ordinary people. The story of my great-great-grandmother became the origin, and I wanted to verify that the children in Aunt Janet’s story were indeed shipped to the U.S. I went to the Emory University website slavevoyage.org and found the Jesus Maria, a ship where the human cargo was, by and large, children. Their names were listed in the log. Phoebe had to have been shipped into the Caribbean and enslaved by plantation owners until she eventually landed in the area of North Carolina and Virginia, where Elvira was born. With that information I set out to write the thirteen poems inspired by history. I was now driven by a passion rooted firmly in the history of my own origins, which provided the creative strategy for writing the suite of poems featured in this column.

When I came across that ship and saw the children’s names I felt a web of emotions: grief, horror, sadness.

In the case of “My Great Great Grandparents Read/ George Moses Horton and David Walker,” again love seemed to be the only choice, but it was a more complex choice in this instance. Phoebe’s son-in-law Ruffin was my father’s grandfather, and my father bore his first name as his own middle name. I began to imagine Ruffin’s parents, Walter and Mary, in the context of George Moses Horton, an important poet, a founder of the tradition, and David Walker, a man who gave his life to the act of resistance and liberation. I wanted to imagine them as connected to the larger pulses of their time. So I spent several weeks trying to get the poem to open to me, to present a central image and an emotional access point.

The poem did not begin until I literally walked into a magical moment with my partner, Kristen, on one of our evening strolls in rural Connecticut where we live on what was once one of the largest working farms in the area, complete with cows and rolling hills. It was a cool evening this past summer, an unusually cool summer, so my partner and I were a bit chilled as we walked up the road back to the house, along the edges under the trees hanging over the small roads that line the county. There was the duck and geese pond at the knoll just opposite us, a few yards farther up the incline. Bales of freshly rolled hay lay in the shades lengthening under the sun setting over the lumpy rise and fall of the foothills around us. The dogs were mostly not minding us, as we halfway minded them. I looked at my partner and was flooded with love. The whole moment was transformed, and I saw an image of my great-great-grandmother Mary carrying a basket of tomatoes around the edge of the pond, an embodied gift from my imagination and my memories.

The other pieces of the poem that suggested themselves during my research now took on form, and I made a decision to make it an assembly of short lyrical pieces. They were as much the product of research as they were my memories of Aunt Janet with her husband, my Uncle Louis, sitting by their fireplace one evening in 1974, when I traveled to the family homeland in Virginia and North Carolina with a notebook and tape recorder. Aunt Janet and Uncle Louis told me stories handed to them by their ancestors, including Ruffin, the son of Walter and Mary, and the woman he married, Elvira, whose mother was Phoebe, the little girl stolen from her home in West Africa. That trip formed the seed of what would become my first book, Water Song. It appeared in 1985, a little over a decade after that evening by the fireplace.

In structuring this essay about Walter and Mary, I have had a chance to revisit foundational parts of my writing process. History has always been important to my work, and although I never thought of my poetry as research, that is indeed what it has been and continues to be. My gaze on the past is one where I invest a lyric tone in what I perceive. When I try to write lyrically in the present, it is with the awareness of the paradox of history, as the only real time is the now. That leaves the poet the joy of celebrating the central place of poetry in human consciousness, that central place where we poets live. In winters here in rural Connecticut, my partner and I look forward to using the fireplace. On the mantle are books that have been important to either or both of us, books we have read from while the fire burned in the hearth, books that speak to humanity and justice. The sun rises and sets on fields that have not changed since the time when Walter and Mary enjoyed a life together, reading by the fireplace, bound in slavery, but freed by the power of love to dream.

This article originally appeared in issue 18.2 (Spring, 2018).

Afaa M. Weaver’s latest collection is Spirit Boxing (2017). He has received four Pushcart prizes, the Kingsley Tufts Award, the Phillis Wheatley Book Award, and fellowships from the Pew and Guggenheim foundations, among other awards.