Five Poems

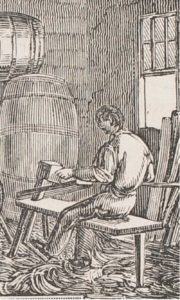

Coopering Lesson, c. 1855

In coopering, the device a cooper uses to hold the stave

is called a shaving horse, or mare.

There’s a rhythm to it,

as Father’s bare hands, arms,

draw the hollowing knife along each

riven stave, legs braced against the

mare’s length, cedar falling in commas

from his aproned waist. It’s the scooping

out that forms each stave’s curve, twenty

or more hollowed in equal arcs before heat,

hoops, windlass, rope bind them in round

certainty—the way parentheses hold in all

we don’t say directly. Next, Father sets

the cask ablaze, char sealing its pores,

flames’ height the clock by which he

gauges time, the line between

destruction and enough.

Commencement

Poem constructed from the words of Henry M. Pierce’s commencement address

to Grace’s class, the first graduating class of Rutgers Female College, 1867.

Of late, the public mind is agitated by the question

of woman’s true position and her proper education.

Equal, I would claim is woman’s place beside of man. I am persuaded

the time is near when we shall marvel this was ever seriously debated.

Along with reason, my opinion rests in Christ’s own Holy view.

How else, in his ideal of marriage, could one truly fuse from two?

It follows that in woman’s preparation for this station,

her schooling should be equal to man’s liberal education.

Graduates, yield not to mean spirits who protest each notch

of woman’s rise is cut from man’s God-given lot.

Civilization’s advance hereafter, or its like decline,

depends on the place each nation gives to womankind.

Stereocard, c. 1893

In the 1870’s, Grace moved to Richmond with her mother;

her sister Minnie remained in New York City.

Dear Minnie,

Thank you for the stereocard, dear sister. Wherever

did you find it? The House of Mansions gone a decade, yet

here, in double, those lancet windows (now rubble) where

once I peered into the heavens. How fast Rutgers outgrew

what seemed enough: crenellated towers, labyrinthine halls.

Moving the college, telescope and all. Do you remember

how, in summer, we’d spread a blanket on grass already

misted with night’s kiss, and I’d read you the stars?

Gazelle is what we saw in Ursa Major, galloping

across the sky (I still do). Why Great Bear?

This card truly transports me to your side.

Still, names recorded are what persist, lines drawn

what we insist on or resist. Take a ship’s register.

At each port, my bare fingers trigger the same label

under “calling”: spinster. As if men study a stereocard

in which a twin image of my spirit is split: half

with laughter, good works, this sisterhood absent

from their senses, pen declaring me only without.

I want to reply, but silence is the only kindness

(can you hear Mother too?). Instead, I recast spinster

to describe how I spin filaments of students’ dreams,

talents, and study into thread, perhaps for blankets

like the one under our heads when we were girls.

At least as Mrs. Young, you’re spared this word,

if not its measure. I recall the line in Mother’s obituary

that halted my tears: Only one of her daughters

is married—Joanna and I as marks against her reckoning.

Love,

Grace

P.S. I should

amend what I said earlier. There is another word

they record sometimes: none.

Böhme’s Theory, c. 1905

Jakob Böhme (1575-1624) was a Christian theologian and mystic.

Dear Minnie,

You mentioned Böhme in your letter, his theory that

God has pressed Himself into the world for us to discover. What if

He is pressed in human invention too? Clothing, buildings, machines.

What if, along with dahlias and the brush of sunrise on the Hudson,

He’s in these things? Then perhaps it’s in these signals combined

that God sends His most urgent messages. Consider those white flags

draped, motionless, on tenement doors, markers hung for children

smothered by summer’s heat—while outside, wind licked and licked

at sheets strung between alleys, nudging corners up like tongues.

This isn’t the reply you expected.

It’s just, of late, I’ve noticed how much around us is designed

to look like something it is not: bloomers like skirts,

chemisette as blouse. Nature deceives as well. Near

Honolulu, the ocean kaleidoscopes with rose,

emerald,

gold,

before settling back to blue.

Yet, it isn’t the sea changing,

but reflections of corals below.

What should we glean from this?

The poem about Death stopping—

you know the one. I rode in such a carriage with loneliness.

Still, I hope for love, companionship. Is this deceit?

At Kenilworth, on our last trip with Uncle Lewis, I plucked holly

from its beautiful ruin and tucked it in my journal. It clings

to green. A pressing? But I worry I overlook more than I see.

Last week, on our block, I discovered steps

sunk into a bank. They led

to a lilac pendant with lavender, house fallen

(or taken) down long ago. How many stairways do we pass

that could lead to our flourishing? Their fragrance lingers

in these halls, that without Mother or Uncle, lengthen. Another deceit.

I miss you, dear sister.

How It Was

Grace Arents died on June 20, 1926. Announcements lauded her philanthropy, some noting surviving relatives. Although Grace left life-rights at Bloemendaal to Mary Garland Smith, her name was not mentioned.

This poem is in Mary Garland’s voice.

How the altar candle wouldn’t catch,

struggling to burn as I struggled for breath.

How people embraced your sister, nephews,

tears passing from cheeks to shoulder sleeves.

How the eulogy, brief as you’d requested,

bid students to mind their studies, parents, prayers.

How they wept into folded hands as I pictured you

kneeling to console each child—arms open, gaze warm.

How when my vision cleared, there was only emptiness

in the pew beside me—the hymns sung, the flame gone.

Walking with Grace: A Documentary Poetry Journey

My journey to learn about Grace Evelyn Arents (1848-1926) began when I moved into a home within walking distance of her last residence, Bloemendaal, now part of a botanical garden named after her uncle Lewis Ginter.

I quickly learned how Grace’s generosity and tenacity transformed the Oregon Hill neighborhood in Richmond, Virginia. Her philanthropy began prior to her uncle Lewis’s death and burgeoned after she inherited a substantial fortune from him in 1897. The mission work of her congregation at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church led Grace to Oregon Hill, a working-class community perched above the James River near Albemarle Paper Company and Tredegar Iron Works. Here, Grace Arents founded St. Andrew’s School and served as its first principal. She funded the building of St. Andrew’s Teachers’ House and a Gothic-style granite and limestone cathedral for St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church (the first in Richmond in which all pews were free), as well as playgrounds, parks, public housing, and public baths. She opened Richmond’s first public library, which later became a branch of the Richmond Public Library, donated money to the city for an elementary school, and helped establish the Richmond Education Association (REA) and Instructive Visiting Nurses Association (IVNA). Throughout her life, she gave of herself and her wealth quietly, and those gifts made a lasting impact. St. Andrew’s School, the church, REA, and IVNA remain active, as does the botanical garden established on land she bequeathed to the city. St. Andrew’s School and Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden (LGBG) continue to be supported, though not solely, by funds left to sustain them by Grace Arents. As I began to understand the extent of Grace’s influence, I realized I was moving about in the legacy of an important local historical figure, but one whose gender and sense of privacy had obscured her story. I was curious: how did a nineteenth-century woman of means accomplish so much, unhampered and unassisted by a husband, and what sort of life did this strong-willed woman live?

Research would not yield these answers easily. In keeping with her private lifestyle, Grace ordered her personal papers burned when she died. Two travel diaries, a commonplace book, and a handful of letters eluded this fate. When I read them, I was struck by the incomplete picture I’d formed of Grace from biographical profiles that depicted her as a prim, religious, shy, determined, private spinster who cared about public education, libraries, public health, parks, gardens, and architecture. I indeed found confirmation of the way she protected her privacy, such as in a letter in which she politely yet firmly declines a friend’s offer of assistance in regard to a scandal involving her niece Edna. Likewise, her diaries and commonplace book affirm her wide range of interests, including several social causes, and her devotion to her faith. Yet Grace also describes natural beauty with a sense of wonder in her diaries, and recounts the fun she had riding a donkey in a street race in Port Said, and times she socialized late into the evening. Alongside sermons, her commonplace book contains poems about love, loss, and friendship. The articles I’d read about her, even collectively, fell short of capturing this complexity.

In addition to these personal documents, I examined census records, historical newspapers, and passenger lists for traces of Grace, and interviewed people who’ve studied her life, like librarians Patty Parks and Janet Woody; Sharon Francisco and Fran Purdum, who portray Grace and her uncle for LGBG’s Heritage Days; Edwin Slipek, professor and editor; and Lewis Ginter’s biographer, Brian Burns. Of all the documents accumulated about Grace in public archives and private collections, photos are the most elusive. A handful taken in profile exist, and there’s a small portrait of her as a child, but because she refused photographs, there’s no front-facing photo of her as an adult, at least none that those I interviewed are confident is her. Yet last year, LGBG included a front-facing photo of Grace in an exhibit about the garden’s history. It could be her, but I’m not convinced. Perhaps I’m resistant to putting a face with her story since she worked so diligently to avoid photographs. Perhaps I’ve grown accustomed to hearing her voice through her words, witnessing her values through her works, and seeing her in that “beside” view of profile photos. Several times throughout this journey, when I might have studied her gaze eye-to-eye across time in a portrait, I’ve instead visited her gravesite in Hollywood Cemetery or walked along the streets and grounds where she lived and worked. With or without a face to picture in my mind, her story inspires me and has drawn me back, again and again, to sources that hold whispers of that story.

When the research process has frustrated me, as I anticipated it would, connective threads between her life and mine have deepened and sustained my motivation to keep searching, studying, and writing. Although Grace lived in a much higher social class than mine, and in a starkly different time, I’ve found echoes of my life in details of hers: her Dutch ancestry, her passion for education and libraries, her move from North to South, and the long-term companionship she found with another woman. And Grace lived and worked and dreamed a mile away from where I’m sitting right now. Let me share some highlights from my journey to create documentary poetry about Grace Arents, using the five poems included in this issue as markers. It’s my hope that the voice and persona in these poems, informed by both research and imagination, convey Grace’s tenacity, mystery, and complex humanity.

One of the first hurdles I encountered, along with the paucity of primary sources extant in Grace’s hand, was developing an authentic vocabulary with which to write the poems. By mining Grace’s words in her travel journals, along with those of poets, writers, and ministers whose lines she copied into her commonplace book, I gleaned lists of nouns, verbs, and adjectives. Then, by delving into subjects on which she focused her energy: education (particularly in home and industrial arts), libraries, public health, horticulture, agriculture, and the Episcopal faith, I expanded this wellspring of words, images, and potential metaphors to form a Grace Arents lexicon. I also kept in mind her affinity for painting and drawing, talents for which she won honors in her graduating class at Rutgers Female College, an affinity reflected in diary entries in which she recorded details about the color, light, texture, and contours of her surroundings, and about the paintings, sculptures, and architecture she noticed.

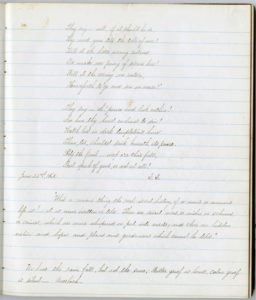

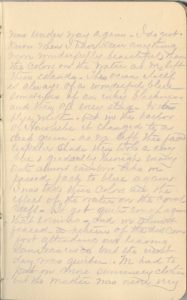

As I immersed myself in the challenge of writing in Grace’s voice, I sensed the tension in the ways she resisted or pushed beyond society’s expectations of women, particularly by overseeing the construction of St. Andrew’s Church. Tension emerged as a recurrent theme in her life, a theme I wanted to introduce early in her story. Several passages she copied into her commonplace book resonate with the tension of things held back or held in, such as the one in fig. 1: “What a curious thing the real, secret history of a man’s or woman’s life is! . . . it is never written or told. There are secret vices, or wishes, or schemes, or crimes, which are never whispered or put into words; and there are hidden virtues and hopes and plans and goodness which cannot be told.”

Her father’s work as a cooper provided an apt metaphor for holding things in, inspiring the poem “Coopering Lesson, c. 1855,” which demanded another layer of vocabulary: the language of barrel-making. Public records show that Stephen Arents died in 1855 when Grace was seven or eight, a fact that established a boundary as to when I could place this poem in time. Fortunately, a verse that Grace copied into her sister Mary’s commonplace book circa 1855, containing lines like “Be thy spirits ever unshrouded,” suggests Grace could read and write formal texts by this same year. It seemed reasonable that she would also have some familiarity with the terminology of her father’s trade. As I revised “Coopering Lesson,” I shaped the form to evoke a barrel so that the poem’s appearance amplifies the tension pressed into its lines.

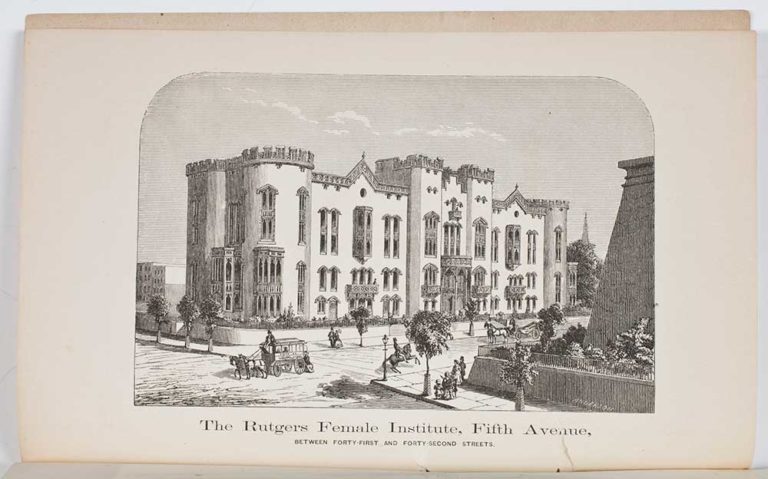

In contrast to the opening poem’s reflection of a broad theme, the spark for “Commencement” came from a specific source, one I found shortly after discovering where Grace attended college. Her 1867 class was the first to graduate after the institution’s name was changed from Rutgers Female Institute to Rutgers Female College. After I uncovered this fact in an article in the June 27, 1867, issue of New York Observer and Chronicle, I found the full text of the president’s address that Henry M. Pierce gave at her commencement in the HathiTrust Digital Library. I had wondered how Grace developed the confidence to operate in spheres typically dominated by men. Pierce’s address provides a glimpse into the educational environment that helped instill such confidence, as reflected in this passage: “I am fully persuaded that the time is not far distant, when it will be thought incredible that the question of the inferiority of woman should ever have been seriously debated. For it is not without higher warrant than that of human reason, that I would claim for woman an equal place by the side of man.” Pierce goes on to assert a faith-based defense for women’s equality and equal liberal education, at one point saying (in relation to an interpretation of Proverbs), “yield not to the mean spirit, that thinks that whatever is conceded to woman, is so much taken from the birthright of man.” As a woman deeply committed to the Episcopal faith (values reflected in her diary and life work), this biblical argument would have resonated with young Grace. The first time I read Pierce’s words, I caught myself holding my breath as I imagined what it must have been like to be a young woman hearing this message nearly 150 years ago. I constructed the poem “Commencement” in the spirit of Pierce’s message, drawing most words for the poem directly from his text.

At this point in the project, my writing stalled. For the manuscript to work, I needed a form that could move the narrative further in one poem than the half-dozen poems I had written so far, a form that could also reveal more of Grace’s personality and language. Taking cues from collections like Natasha Trethewey’s Bellocq’s Ophelia, and Anna, washing by Ted Genoways, as well as advice from my poetry mentor Laure-Anne Bosselaar-Brown, I began to write epistolary poems addressed to the sibling who outlived Grace: her sister Minnie. By addressing Minnie, the poems in Grace’s persona could follow the full arc of Grace’s life. Since Minnie and her daughter Edna accompanied Grace on an overseas trip with their uncle Lewis (as documented in Grace’s 1896 travel diary and in passenger lists) this choice could also provide opportunities to make direct references to their shared experiences. “Stereocard, c. 1893” and “Böhme’s Theory, c. 1905” are among the letter poems that emerged.

“Stereocard, c. 1893” centers on a metaphor evocative of a photographic method familiar to Americans in the Progressive era, particularly to travelers like Grace. Through historic images and newspaper articles about Rutgers Female College and the elegant House of Mansions where the college was located when Grace attended, I learned about the towers, windows, and telescope referenced in the first stanza. Given the building’s stature, it’s likely that a stereocard of the House of Mansions actually exists, although I haven’t found one yet. Ship’s registers in genealogical databases revealed the words “spinster” and “none” listed beside Grace’s name under “calling.” In the third stanza, the italicized text “Only one of her daughters is married” is excerpted from an obituary for Grace’s mother, Jane Arents, that was published on the front page of The Richmond Dispatch on July 30, 1890, a document available through Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

Similarly, “Böhme’s Theory, c. 1905” knits together period details with documentary traces of Grace. Given her wide reading on a variety of topics, Christianity among them, Grace would likely have known of Böhme. Likewise, considering her dedication to improving living conditions for the working-class Oregon Hill community and her continued ties to New York City through family members who remained there, Grace would likely have been aware of tenement conditions. Her frequent inclusion of poems in her commonplace book makes it likely she would have read Emily Dickinson’s poems after they were published in 1890. Along with these historical contexts, Grace’s 1888 travel diary provided details about clothing items like bloomers and the description of shifting colors in the waters near Honolulu, an excerpt which appears in fig. 5. It reads, “I do not know when I have seen anything more wonderfully beautiful than the colors on the water as we left these islands—This ocean itself is always of a wonderful blue sometimes of an inky blackness and then of every stage to a blue white—but in the harbor of Honolulu it changed to a deep green—as we left this faded to a paler shade then took a rosy hue & gradually through many tints almost rainbow like we passed back to blue again. I was told these colors are the effect of the water on the coral reefs.”

Later in the poem, the story about plucking holly from the Kenilworth ruins is drawn from Grace’s 1896 diary, while the phrase “pendant with” echoes her 1888 diary description of forests near Monterey “where for the first time [she] saw. . . Florida moss pendant from the branches of the trees.” Other epistolary poems in the manuscript reflect a kaleidoscope of source material as well.

Along with my desire to understand Grace’s life, ever since I first read about her, I’ve wanted to know more about the companion to whom she left a modest inheritance and lifetime rights to reside at Bloemendaal: Mary Garland Smith. Unfortunately, the last name Smith has made tracing her story even more frustrating than finding fragments of Grace’s life in public documents and historic records. Yet I’m grateful that even this search has yielded a few tiny bursts of research joy. School and census records confirm details commonly recounted in articles about Grace, such as Mary Garland Smith succeeding Grace as principal of St. Andrew’s School. The 1910 census shows that Mary Garland Smith was residing at St. Andrew’s Teachers’ House and “Principal” was noted as her occupation. In 1920 and subsequent census records, she lived at Bloemendaal. The 1920 and 1940 census records also indicate that she was born in Virginia and suggest she may have preferred being called Garland rather than Mary. The 1920 census lists her as Garland M. Smith, the 1940 census as M. Garland Smith. Even if she did not go by Garland with everyone, the codicil to Grace’s will includes this statement: “I have left the Farm with everything on it to Garland for her life.” When I extended my search to genealogical databases, I found her 1922 passport application and a passenger list for the SS Scythia’s voyage from Liverpool to New York that August. In case you’re wondering (as I was), Grace’s name does not appear on the same passenger list. Still, the application reveals Mary Garland’s birthplace as Essex County, Virginia, and includes a photograph and a description of her appearance.

When I make presentations about Grace, people often ask whether Grace and Garland were a couple in the sense that some women, like my wife and me, are today. It’s certainly possible, but since there are no records that suggest romantic ties, I’ve chosen to imagine them as close friends and companions who loved each other, shared a passion for education, and who knew each other for at least 19 years, from 1907 when Mary Garland Smith became principal of St. Andrew’s School until Grace’s death in 1926. In their era, intimate friendships among women sometimes sparked scrutiny; however, women in Grace’s social class were less often subjected to such critical examination. Along with Grace’s fierce protection of her privacy, their choice to live together outside the city on a farm at Bloemendaal further shielded them. It did not surprise me when I discovered that despite their companionship and the life rights Grace granted to Garland in her will, none of Grace’s obituaries mentioned Mary Garland Smith. Although it’s impossible to know how Garland felt about this omission, I expect it mattered little to her compared to the absence of Grace. It is this loss of a dear friend and the sense of emptiness that follows that I’ve tried to capture in “How It Was,” a poem from Garland’s perspective.

My journey with Grace and Garland is still in progress. I’m grateful that my work has already connected more people with their story and augmented the details in the Grace stories that are told, such as the inclusion of her graduation from Rutgers Female College in an LGBG display about the garden’s history. The five poems published here represent part of the narrative arc for a book-length manuscript about Grace Evelyn Arents. Yet questions remain. Where did Grace stand on suffrage? Did she correspond or work with Maggie L. Walker, a famous contemporary of hers? Was she involved in responding when the 1918 influenza epidemic reached Richmond? Did Grace and Garland ever travel together? What did Garland do before she became principal of St. Andrew’s and after Grace’s death? Several poems I envision in the arc of their story require additional research before I put pen to paper. I continue to research, learn, and write, and to walk with Grace—and Garland.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3.5 (July, 2016).

Wendy DeGroat’s poetry has appeared in U.S. and U.K. publications, including Raleigh Review, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, About Place, Mslexia, and TRIVIA: Voices of Feminism. With roots in northern New Jersey where her ancestors’ 1865 cabin was restored by Montclair State University to serve as a site for teaching early American history, she is currently a librarian in Richmond, Virginia, where she also teaches writing workshops and curates poetryriver.org, a resource site for reading and learning about documentary poetry, and for diversifying the poetic voices taught in high school and undergraduate classrooms.