The Pocahontas Archive

For over a decade, English professor and digital humanist Ed Gallagher’s History on Trial Website, hosted by Lehigh University’s Digital Library, has been making its appearance in my early American literature survey. Gallagher describes the site as a “collaborative shared resource” for use in electronic learning environments. The site houses “inquiries into controversies over the representations of history.” These inquiries take the form of curated collections of digital materials for teaching six controversy-inciting events and/or figures in American culture: the “discovery” of the Americas, Pocahontas, filmic adaptations of American history, the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Enola Gay, and the Vietnam War Memorial.

Created and maintained by Gallagher as an open source for faculty and students at universities and high schools, History on Trial is the product of collaborations among graduate students, Lehigh faculty, librarians, technical staff, students, high school teachers, and early Americanists nationally. Operating on the premise that representation matters, the site conveniently archives textual and visual artifacts for teaching about the early Americas. History on Trial provides a digital archive of literary and visual representations related to the six problems of representation Gallagher identifies.

This review focuses on those pages most interesting to readers of Common-place: “The Literature of Justification,” “The Pocahontas Archive,” and “The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy.” The History on Trial main page identifies specific questions that shape each page (or controversy). “The Literature of Justification” focuses on the question, how did Europeans and early settlers rationalize their incursions into North America? Other organizing questions include, did she or didn’t she save John Smith? (for “The Pocahontas Archive”), and, was Jefferson a “hypocrite or hero”? While the controversy template runs the danger of oversimplifying history and representation (more on that later), the rich materials in this archive can be used in complex ways.

Developed from Gallagher’s English graduate course “Early American Literature: America’s Many Beginnings,” “The Literature of Justification” presents chapters on the papacy, New Spain, Roanoke, Newfoundland, Jamestown, Pennsylvania, and the Supreme Court. The “About” tab unpacks the guiding questions of the course, drawn from literary authors, historians, and legal scholars. The guiding questions center on how Europeans narrated the process of settlement, colonization, and expansion. Resources for these questions are listed in the usefully annotated “General Bibliography” tab. The next tab, an interactive version of Ortelius’s 1606 map of North America, shows which entities had stakes in each region. The “Sound Bites” tab includes over three hundred “provocative excerpts from primary and secondary sources” pertaining to the guiding questions. This library of relevant, quick-hitting passages is also keyword searchable, enabling users to compare a range of writing about the colonization of North America from Thomas Harriot to Homi Bhabha. For example, searching the term “rich” yields three sound bites from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, while the word “savage” yields sixty-two from the fifteenth through the twenty-first centuries.

Each chapter of “The Literature of Justification” addresses a specific colonial stakeholder (the papacy, Supreme Court) or colony (New Spain, Roanoke, etc.). The consistent template—introduction, timeline, graduate student essay, annotated bibliography, and image gallery—orients users from chapter to chapter and provides continuity when moving among chapters.

The most evolved chapter, Jamestown, includes WMV videos produced by Lehigh University graduate students and faculty, but they were not operating when I tested them with Safari and Chrome. The “Teaching” tab links to curriculum mapping for “Teaching British Literature Using Writings from Jamestown,” developed by honors English high school teacher Jane McLemore using Virginia Standards of Learning. The “Teaching” and “Introduction” tabs offer the most opportunity for collaboration among faculty and students at various levels; each page invites users to contribute to the work begun by “first and second generation” graduate student editors and authors.

“The Pocahontas Archive” extends the History on Trial motif to the question of Pocahontas’s relationship with John Smith and the cultural mythologies at work in representing the figure known to the Powhatan as Matoaka. Perhaps most impressive is the monumental effort to collect “materials relating to the study of Pocahontas (and, by association, John Smith, Jamestown, and early Virginia) from early America to the present day.” The archive offers a staggering record of the colonial and U.S. obsession with Pocahontas as a foundational figure in its national mythology.

At the “History” tab, one finds three sections. The “Pocahontas Time Line” provides a chronology of events relating to Pocahontas or her representation from 1595 (the probable year of her birth) to 1899 (completed to 1861). Following the time line is a page called “The Facts,” which attempts to compile all mentions of Pocahontas in the historical record using documents through 1630. Finally, this tab includes a page of epithets used to describe Pocahontas from 1608 through 2003. The “Controversy” tab presents native and western responses to the story of Smith’s rescue by Pocahontas. Mattaponi Sacred History is presented as a list of points derived from Paula Gunn Allen’s (2003) and Linwood and Daniels’ (2007) native biographies of Pocahontas. The “Debunking” page provides an extensive annotated bibliography of books and articles that bear on the question of whether or not Pocahontas actually saved John Smith.

Especially impressive and useful for high school and university faculty and students is the annotated bibliography of over 2,000 entries pertaining to Pocahontas, which is sorted chronologically and is fully searchable. As with the “Debunking” bibliography, electronic full-text documents are linked to the listings where possible. Gallagher has also provided a list of key search categories, mostly related to genre (image, dissertation, musical, novel, etc.).

The “Essays” tab leads to faculty and student work on representations of Pocahontas in texts, images, and film, and a section on her purported rescue of Smith. These essays, the work of advanced undergraduates at the University of Minnesota, and graduate students and faculty at Lehigh University, demonstrate how this unique digital collection offers a range of creative possibilities for students and faculty. Indeed, Gallagher invites interested faculty and students to contribute to the “Essay” and “Teaching” sections.

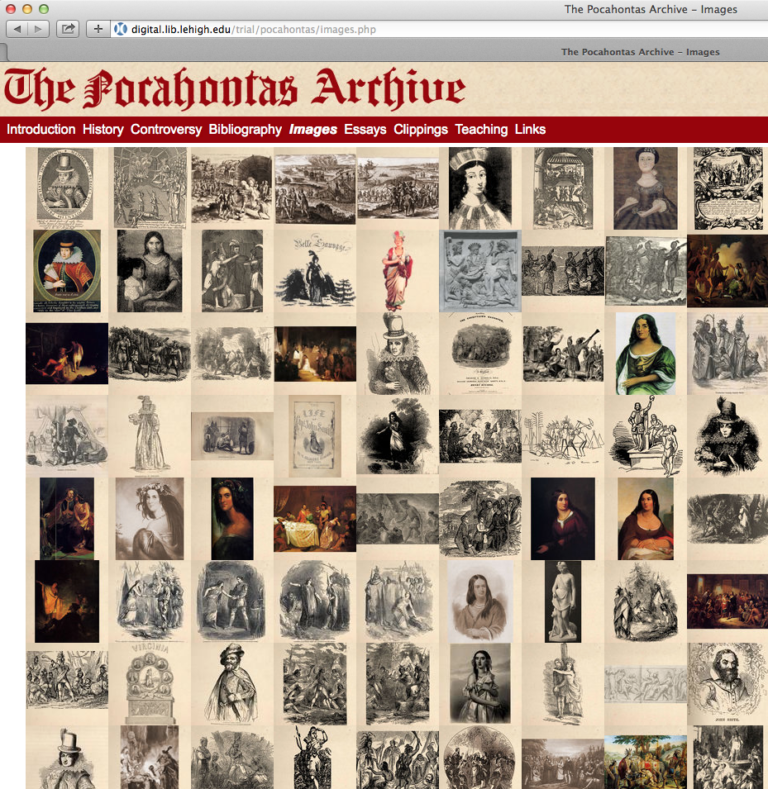

The centerpiece of “The Pocahontas Archive” is its image gallery, which houses approximately 175 visual representations of Pocahontas, beginning with Simon Van de Passe’s 1616 engraving, “Matoaka als Rebecca,” purportedly completed while she was alive. Presented as an index of thumbnails in chronological order, each image, when selected, is carefully cited and, where possible, linked to an electronic version of the original. For students who know of John Smith only from Disney’s Pocahontas, opening up the image index reveals 400 years of representation and appropriation in thumbnail form. The visual gallery showcases how the figure of Pocahontas has been appropriated, demonized, romanticized, and fetishized. The “Clippings” tab accomplishes what the “Image” tab does only via text; this tab collects over three hundred quotations about Pocahontas by diverse authors, such as students, scholars, poets, and playwrights. The clippings are randomized by choice, but users can perform keyword searches or select “Get 5 Random Clippings.” This explicit refusal to sort invites users to make their own meanings with critical thinking. “The Pocahontas Archive” is conducive to in-class activities. Students can explain how particular images construct Pocahontas or explain how specific clippings or texts are illuminated by an image.

“The Pocahontas Archive” is a stunning, living resource that collects diverse media artifacts from their scattered, sometimes obscure locations into one accessible, easily navigable resource. For both faculty and students, the site promises capacity and creative possibilities for critical thinking and bricolage that textbooks cannot. In focusing on problematizing colonization or the figure of Pocahontas, critical engagement is, to some degree, built into the structure of the site. This problematizing works best when presented through a range of perspectives, rather than as a binary opposition. As Miriam Posner observes, the models we use in digital humanities—especially as we are still figuring out what we are doing—often replicate structures of power, including gender and race, in uncritical ways. “The Pocahontas Archive” resists reifying structures of power by placing Mattaponi sacred history on a par with academic scholars and primary texts. Dr. Gallagher could go even further by including more Native American perspectives and contexts, which would eliminate any perceived binary (Mattaponi vs. western academics). For example, what can we know about the roles of Algonquin girls and women from baskets or wampum?

This challenge to avoid replicating the power structures that constitute present-day experience informs the “Jefferson-Hemings Controversy” site, a series of sixteen episodes that track the media representation of Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings from its sensationalized beginnings to the present day. Each episode organizes a cultural moment in the history of the “controversy,” through an overview, primary and secondary sources, clippings, commentary, essays, teaching tools, and images. As with “The Pocahontas Archive,” the information presented for each stage of the controversy is wide-ranging and extensive. And as with Pocahontas, the actual Sally Hemings is noticeably absent from the archive except as a (vilified, sexualized, objectified) figure in Jefferson’s controversy. Because the site is set up as a controversy, the episodes in many ways elide its central fact: A slave woman was raped by her white master. If the controversy drives the site, then Hemings’ position cannot be adequately addressed. Instead of a debate featuring the opinions of those who have been authorized to speak, perhaps a template that challenges binarisms is in order. In “’The Cause of Her Grief’: The Rape of a Slave in Early New England,” Wendy Anne Warren reconstructs the life of an unnamed seventeenth-century slave woman using a dizzying array of far-flung sources to demonstrate what it is possible to know about this overlooked figure. After a spectacular tour of her sources, Warren concludes, “We have known, for a long time, a story of New England’s settlement in which ‘Mr. Maverick’s Negro woman’ does not appear; here is one in which she does.” Warren’s investigation emphasizes the slave woman’s life and imagines her perspective on the events described in the archive. I suspect that dispensing with the binaries of controversy could yield something similarly human: an archive that goes beyond the black and white dialogue that shapes the soundtrack to our twenty-first-century lives.

As Common-place transitions to its new look on our new Website, the Web Library is adding a feature to our collection of reviews of online resources for the study of early American history and culture. The Web Library now includes a searchable list of digital projects on topics in early American studies. We encourage Common-place readers to add to this list of digital resources by contributing to the Zotero group suggestion box for Common-place Web Library or by e-mailing suggestions to Web Library editor Edward Whitley. In addition to our regular reviews of digital resources for scholarship and teaching, the Web Library will also become a forum for reflections on digital humanities practices more broadly conceived—a place where both the users and the creators of digital resources can reflect on the opportunities and challenges that digital methods present to the study of early American history and culture.

Further reading:

Miriam Posner, “What’s Next?: The Radical, Unrealized Potential of Digital Humanities.” Miriam Posner’s Blog, July 27, 2015 (October 1, 2015).

Wendy Anne Warren, “’The Cause of Her Grief’: The Rape of a Slave in Early New England.” Journal of American History (2007): 1031-1049.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.1 (Fall, 2015).

Lisa M. Logan is associate professor of English at University of Central Florida, where she teaches early American literature and feminist theory.

![Fig. 2. Male and female passenger pigeon. Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology, or: The natural history of the birds of the United States, 9 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1808-14) 5: 110-13. The accompanying text refers to the "vast numbers" that are shot and the "waggon loads of them that are poured into the market …[so that] pigeons become the order of the day and dinner, breakfast and supper until the very name becomes sickening." Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/216-300x222.jpg)