King Philip’s Hand

Prologue

I had begun so many times.

With snow, with leaves, with wind and rain,

with a white initial A of sail,

with a woman’s voice recalled, with syllables

stilled centuries ago, with faces in the trees,

in the windows, in the fog.

I had begun so many times

before the tiny rubric of the crab’s claw appeared

in my palm, curling out from its scavenged shell,

just before the fog.

Before the cold rain began in my shoulders.

Before the fog.

Down where the ocean melts to a sheen,

looking back toward dune grass, the charred log

where my family sat, I watched the infiltration of the pines,

the vanishing of the islet we had planned to explore.

Then it was upon them,

or rather it erased us all—it poured through everything,

until I had just ten yards of water, sand, and white air to see,

the sun a spun nickel at my shoulder.

I was being brought about again.

Mutterings wavered up, strangers trembled past with awful smiles

and disappeared.

So now, say it, they said, say what

you knew of the earth, the where of it, the truth of it,

what soil, sea, what wind prevailed, what voices in your blood,

when it was blood, when it was wind,

when stars sang into your body as you lay there on the stones,

breathing there, remember, so long

it came to seem looking out as from the whole

planet’s vast, sloping side.

What was given you to know?

Ogwhan

Ogwhan

Let the boat drift

Nickquenum nittauke: mishquawtuck

home to cedar trees.

Wunnagehan sowanniu.

before a southwest wind.

Belong there, settle, claim

at last the scents and leaves, the moody tidal song

of channel bells.

You will lose them just this way,

lose life after life.

I have begun so many times.

Begin again.

King Philip’s Hand

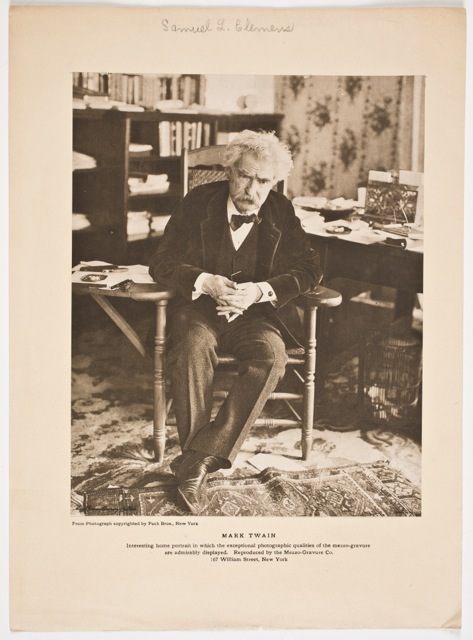

In Memoriam E. M. F. 1900-1978

It is characteristic then, of what I have called ‘angelic’ consciousness that it does not develop a separate, hidden, inner world of private thoughts and feelings. These Beings reflect, or pass on, the light they receive from above; and that is their inner life. Or we can put it that they do indeed have an inner life, but do not feel it as being exclusively their own…not in the sense of [it] being at their disposal. …On the occasion of the Fall, all this was changed by the intervention of Lucifer. Lucifer induced man to begin hiding and hoarding his inner life, and to take pride in it—as a ‘room of one’s own’—making it into something separate and detached alike from its outward manifestation (nature) and from the inner world of spirit beings… Man is now started on the long road which ends in his present normal relation to Nature, wherein nature is not merely his own outward manifestation, nor that of the higher Spiritual Beings who shine through him; whereinnature is not a manifestation at all, but an object—a finished work.

Owen Barfield

There they were, dignified, invisible, Moving without pressure, over the dead leaves, In the autumn heat, through the vibrant air, And the bird called….

T.S.Eliot

Everything only connected by “and” and “and.”

Elizabeth Bishop

When the old Plymouth lost its brakes

on the bridge’s far slope she didn’t say

a word, just shifted down to an empty lot,

stopped them short with the parking brake,

raised a hand to her lips, and smiled at him.

Ten years later, when he’d drive her to market

or the clinic, and she’d say “Home, James”

in her amused, quavering voice, he’d recall

the flicker of triumph on her face that day,

as though she’d been modestly enjoying

what she’d have called pluck, what now

was letting her live out winters alone

beside the bay. She had a cheerful dignity,

humorous self-possession, and a streak

of unpredictable severity, but he could bear

her gentle admonitions, about speeding,

sex, seamanship—even her once saying

she hoped he wouldn’t always be an angry

young man. So he keeps yearning her back

across the lost waves, the old moraines,

longing, and fearing her arrival.

She was interested

in history, (they were on the way

to Gilbert Stuart’s house the morning

the brakes failed), and so one summer

suggested he accompany his cousin

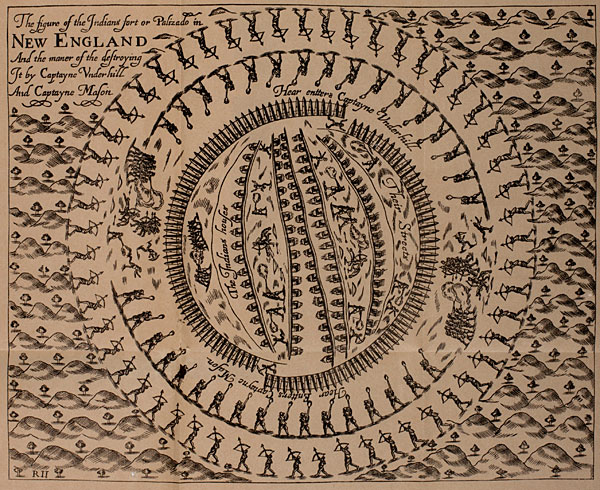

to the museum, near Philip’s last

stronghold on Monthaup, his people’s

summer home—a spring, the granite throne.

There they sorted moccasins, and built

a wigwam with a student of anthropology

from Brooklyn, a young bearded man

whose anger took an ironic, Marxist form.

The museum was near the bridge, minutes

from an estate where they learned tennis.

No wonder he had them pegged: no hope,

or worse, the first who would perish

in the revolution’s maw. In their whites

and sneakers they were helping make a story

out of items—that gentle catalogue of what’s

presumed an extinct way of life, recalled

as a romance by those who murdered it.

Arrowheads and spearpoints, wampum

and beads—that frail dome of saplings

and bark they struggled to lash up said more

about their habits than lost cultures, but their

lives depended on finishing that hut, upon

reading labeled items under glass, selected

and arranged like stones for a path the mind

might follow down to the waters…

*

Mud became the shale the glacier

crushed to stones we heaved as

children by the hour into whitecaps,

to become the gravel becoming

the sand piling at the tidemark. Legend

says that with the Devil’s help, Philip

could throw a stone from Mount Hope

a mile across the harbor to Poppasquash…

I would call her back, who passed

such history on to me. But I never

learned the faith she used to compose

past and future, that let old portrait

figures, villains, heroes, plain,

goodhearted sorts from several

centuries go about their lives

and works all at once in her mind,

as in some busy village Brueghel

painted. Now as the land she knew

is vanishing, her shadow comes

in me to belong somehow with Philip’s,

like contraries the mind feels

obliged to hold together—the strange

comfort of distinction made and

overcome at once…

That is not your piping voice, not

your deliberate passage from the porch

to the kitchen, not your sigh heaved through me,

but it is, it isn’t merely a gust of southwest wind.

The cardinal in the big oak isn’t answering,

he is keening twice, then eight bunched,

rising whistles back to me, three times,

and then he adds cadenzas, until I cannot

say it back.

Cuppyaumen.

Pashpishea.

Mequaunamiinnea

Now you are there.

Moonrise.

Remember me.

Memory, no wish to be a hero

made Philip sayI am determined not

to live until I have no country.Even if

his scattered bones calcified beneath

this earth, no prayer, no spell, no

moonrise will bring the lost to voice.

Salt wind on our skin is not their touch.

Aloof and disappointed, they only seem

to wake in episodes of our making, beneath

the wind-ridden trees, the driven clouds.

| Cowwewonck. | ||||

| Soul. | ||||

| Wunnicheke. | ||||

| Hand. | ||||

| Keesauname. | ||||

| Save me. |

In her last years she wondered aloud

only whether she would recognize

her husband. I pretended to remember him

more clearly than the sharpest recollection

I have—clinging to his shoulders as

he swims toward a float. Could I reach

him, or even Philip in their afterworld,

I’d ask if they could locate her. And look

what I have done now, stranding her under

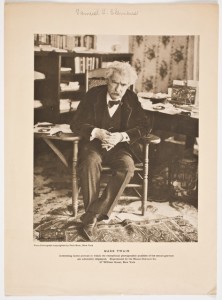

Matteson, in my life’s encyclopedia,

across from Metacomet, far from her William.

Surely someone who knew them both to love

will put this right. And I think she would

forgive me, having called me more than

once by her lost son’s name, dead suddenly

at about the age I was when she died.

Yes, I seek him rowing there among

a moonlit fleet of boats at anchor. There are so many

places to look.

|

Halyards gently slapping, an unlashed tiller some twenty years apart… just the continental wind… |

The wind is long and shadow-flagged The breath upon your knuckles |

Mere associations

that’s all, dissolving from reverence to humor,

disappointing hope with common sense.

My ancestors read and read their holy

dictionary for signs of their god’s will;

the random verses they lit upon made

metaphors with practical results—

destinies, space for English names to creep

west across the blank, benighted maps.

The winters here are hard, the bright spaces of the snow as

smooth as vellum. Deerprints and sticks look like words I

cannot read, just at the dark edge of the forest.

Listen, poor shadow, whirled among

the cedars. The bell, whose bird-limed

clapper we held silent for five minutes

one moonlit wild night years ago,

the bell goes on, telling the channel passage

to the ships, searing the darkness white

an instant, clanging, clanging.

This is the passage through, the right of way,

all else is damnation, a wilderness of death.

Now that you wander, I know why

you told us more than once of that

Longley cousin. Taken, after

witnessing the slaughter of his parents,

he begged his captors to let him

return, just to set his father’s cows to forage.

When he kept his promise and returned

to the tribe, they adopted him, and when years

later relatives redeemed him, the story goes

they had to bring him back by force. Claimed

by twenty stark Quebec seasons, he had

wandered, couldn’t return to ownership,

the stonewalled plots of Groton. He grew

old, of course, and well-to-do (why

his story survived), but I have always

wondered what became of his two

sisters, and if you trembled to think

of them, or envied how they really

must have come to know the countryside?

As we know it now. Disaforested, routed, claimed,

a prospect of some acquiring mind. The dead have always known

what they, what you have done.

Fear their smiling. I was a teller of

stories. I am a story now.

The living suppose the stories belong to them.

But you seemed to bless my reverence

for waves and stars and trees. Because

it was your nature to love kinships,

affinities, or just the apt and lovely names

of things, I thought you left mere causes

and effects to the sententious…

It is not as you suppose. I pass freely in the light between the worlds.

No one needs to hold the quahog shut, answer the bird, fasten the blossom

underneath the apple.

We can hear the sad improvisations inside the silent one, the snarl within

that one’s smile, all the threnodies of resignation, shame, desire,

but we cannot connect them, only listen.

When you spoke your hand would

undertake a gentle dance, fingers

tamp your thumb, drumming

syllables out upon a chair’s arm,

a table, your lap. When you lay

down beneath a shawl on the daybed

under the window, your eyes

would strangely drift and close

while you spoke, but your hand

would flutter up with remembrance,

as if in the chambers of the years

to choose, cherish, caress what those

chambers would contain.

Items.

Exhibits. Evidence. That way of taking

the world was old and well in New England,

brought here like the germs thrashing

inside the Pilgrims, before they were the land’s…

Exempla, symbols, wonders, the argot of god.

Divers Indian baskets filled with corn…

Today, on the way to cross

the Mount Hope Bridge we paused

beside the old stone walls near the north end

of the road. Hooves that forever changed this

soil (trampling the maize of Satan’s children)

stamped in the clover, while my sons counted

the black, fly-tormented backs.

And I saw that all I can give to them

are curiosities, assembled under glass

or foggy legend: the sachem’s jawbone

Cotton Mather kept, the black stone Philip

hurled across the harbor, the brass button

he tore from the emissary’s coat, saying

this, this, is what your English religion

means to me, the Tyrian whorls inside

the quahog shell, the vile self-regard

of believers in the mirror of their faith,

the scalp’s hot, moist peeling from

forehead to nape, the word of twenty

natives valued as that of one who prayed,

the mourning dove’s doxology, the sachem’s

son, nine years old, spared, to be sold

in the Indies. Items. Dis-rememberment.

Poor shade, walker, old woman I loved,

gone now with all the lost, lost one, you

didn’t say this land you gave us once

belonged to Church, deeded him in

gratitude by the magistrates he saved

from the great, doleful, dirty, naked beast.

Their holy war came down to musket balls

and butchery, but the tale’s essence isn’t

cruelty, gross injustice, nor ferocious

piety. It’s how fitting was the payment

made to the one who betrayed the sachem’s

whereabouts to Church, and how he displayed

the wonder of it all around New England,

surviving on the coins he charged to view it.

And they didn’t fear it, all those avid

readers of signs and wonders…

Now in my imagination a kindred

habit lives—gorging on remorseful

supposition, sometimes with the terror

of one holding closed a grievous wound,

it works at telling the world back whole

as it knew, beginning with the accidental

talismans, details that almost cohere,

but will not comfort. How naturally

it seemed to come to you, a dominion

I would covet if it still seemed possible—

whatever flower, bird, fish, or person

found dead or living, named, gathered in…

whose bodiless curse would be a thousand

times more terrible than any word to me…

I cannot revive the song that water and wind

and your old house sang in me, nor

the sons you lost, the son I was when we

played evening checkers, your ancient,

waist length, wild hair, drying in firelight,

nor that terror when I found you waiting

up past midnight on the stairs, to warn me,

frighten me, look right through my after-

glowing rapture with some girl…

All I picture now

is your hand upon the tablecloth—

liver-spotted, translucent skin, the palm

pale, vulnerable, the fingers beating

gently beneath your words. Your hand.

And Philip’s hand, Metacomet’s stiff,

burled hand, cured in a pail of rum.