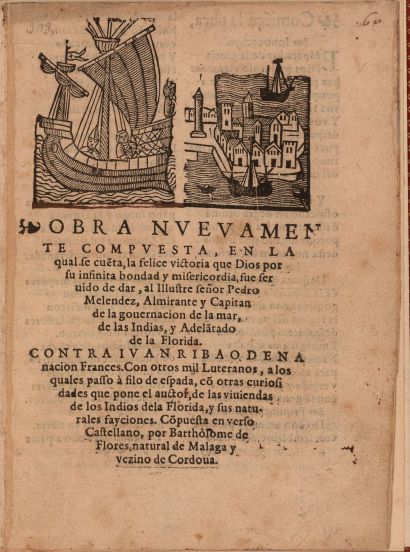

La felice victoria: Bartolomé de Flores’s A Newly Composed Work, Which Recounts the Happy Victory That God, in His Infinite Goodness and Mercy, Was Pleased to Give to the Illustrious Señor Pedro Menéndez (1571)

Translated by E. Thomson Shields Jr. and Thomas Hallock

In spring 1562 the French explorer Jean Ribault cruised the north-flowing St. Johns River, what he called the “River of May,” below present-day Jacksonville, Florida. Two years later, the Calvinist Huguenot explorer René Goulaine de Laudonnière established a fort nearby, challenging shipping lanes off the Atlantic coast. The French Protestant threat caught the attention of Roman Catholic King Philip II, who sent the formidable Asturian Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to eradicate the fort and establish a Spanish fort there. Acting as Adelantado, an entrepreneurial governor who invested his own money in the enterprise, Menéndez answered his charge with military and religious zeal. He demolished the French fort, slaughtered most of the Huguenots, and established St. Augustine—a city that now bills itself as the nation’s oldest continuously occupied city. The year 2015 marks the 450th anniversary of these events, and with the commemoration of St. Augustine’s founding, it serves to recognize that the European contest for la Florida held literary as well as historical importance.

An outsized body of writing emerged from the struggle for this obscure corner of empire, one work being Bartolomé de Flores’s 1571 La felice victoria que Dios por su infinita bondad y misericordia, fue seruido de dar, al Illustre señor Pedro Melendez (The Happy Victory that God, in His Infinite Goodness and Mercy, Was Pleased to Give to the Illustrious Señor Pedro Menéndez). Flores’s poem, published in eight quarto (20 cm x 15 cm) pages and translated here for the first time, has three parts. The first part includes a brief invocation, followed by a description of Menéndez’s charge against the Huguenot settlers, which Flores freely sets against the range of Spanish conquests in the Americas. The second part celebrates the beauty, natural resources, and people of la Florida—again, situating the wonders of one colony against broader imperial claims. A villancico, or carol, finally, sings of a joust, offering Menéndez’s victory as a martial conquest for the Christian realm. The parts may appear disjoined, but in its loose associations, La felice victoria provides a valuable window into Spanish perceptions of empire.

Flores’s verse tribute adds to the substantial—if undervalued—literature about St. Augustine’s founding, a body of work that cuts across several languages and rhetorical positions. Before the Spanish attacked the French Huguenot colonial efforts, Jean Ribault, in England because of the religious wars in France, penned The Whole & True Discouerye of Terra Florida (1563), a book-length promotional account of the St. Johns expedition that mixed pastoral jubilation with topographic detail. At least two early English poems described the far-off territory. Robert Seall’s 1563 broadside, A Commendation of the Adventerus Viage of the Wurthy Captain M. Thomas Stutely Esquyer and others Towards the Land Called Terra Florida, paid tribute to Thomas Stucley (or Stuckley), who vied to set up a colony there. And a slightly better-known 1564 ballad would ask, “Have you not h[e]ard of floryda,” where natives “Fynd glysterynge gold / And yt for tryfels sell?” The swift Spanish victory and dubious Huguenot defense in 1565 sparked a considerable body of writing, much of it legal or procedural, and often with a rhetorical agenda. Multiple biographies of Menéndez chronicle the battle for la Florida, and French survivors penned two accounts. Laudonnière’s L’histoire notable de la Floride (1586) was published posthumously and translated in part by Richard Hakluyt, while Nicolas Le Challeux offered his own version in Discours de l’histoire de la Floride, contenant la trahison des Espangnols, contre les subjects du Roy (1566). The most famous record of this imperial struggle, finally, came from Jacques le Moyne de Morgue, whose 1591 Brevis narratio eorum quæ in Florida Americæ provincia Gallis acciderunt … (Brief Narration of Those Things Which Befell the French in the Province of Florida in America …) included Theodore de Bry’s engravings of native Timucuans, spurious images of Florida’s “first people” that circulate widely to this day.

Many of these sources are known to historians and critics, although La felice victoria has escaped attention. Scholarship on this and other scenes of imperial struggle has remained fixed on the accounts of participant-observers; quasi-literary works have found their way into undergraduate textbooks and appear ripe for commentary, even by scholars who do not read Spanish. But a poem, especially one by a non-participant, does not carry the same historical weight, leading to its neglect. Yet La felice victoria illustrates how empire was understood in Spain, how victories were celebrated, and how the little-regarded territory of la Florida fit alongside more significant triumphs.

What little we know about Bartolomé de Flores comes from his work. Between 1570 and 1572, he apparently experienced a burst of energy, resulting in five verse pamphlets. According to La felice victoria, Flores was “natural de Malaga y vezino de Cordoua,” a Malagueño living in Córdoba. Internal evidence highlights Flores’ being Malagueño, especially the presence of seseo, the Andalucían pronunciation of z and s both pronounced like the letter s in English. Another pamphlet poem identifies Flores as a “colchero,” or quilter, suggesting he was a middle-class tradesman. These verse pamphlets reflect everyday attitudes of the times about Spain’s engagement with the world. Some are laudatory, praising victories in the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula or celebrating the marriage of Princess Anna, daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. Others tell of the 1570 earthquake in Hungary, floods in Flanders, and losses by the Muslim armada of Turkey. The range of subjects indicates that Bartolomé de Flores wrote from reports, not experience. As such, La felice victoria is a valuable record of popular attitudes and beliefs—a source of insight into middle-class Spanish attitudes toward imperial rivalries, perceptions of native peoples and resources in places like la Florida, and for the suggestion of how victories like the one by Menéndez were celebrated.

This translation continues the effort of early Americanists to recover forgotten traditions for twenty-first-century readers. The documentary transcription of the original is included because, although there was an edition of the poem published in 1898, it contains errors and takes a few liberties with the text without marking them. Regarding form, the bulk of La felice victoria is in copla real (with exceptions), i.e., stanzas of ten rhymed octosyllabic lines, with the closing villancico in mainly stanzas of eight octosyllabic lines. Our translation does not attempt the impossible task of replicating the rhythm or rhyme scheme, and because Flores often sequenced his thoughts around end-rhymes, we take some liberty in reordering the lines for fluidity. The goal has been to render a poem in English, not a literal rendering of the Spanish. Those who want to compare the translation with the Spanish are encouraged to use the side-by-side transcription and translation or to consult the page images.

The editors initially worked separately and unbeknownst to one another. E. Thomson Shields Jr. prepared the transcription from a copy at the John Carter Brown Library, and we later consulted scans generously provided by the JCB. The following translation was developed by comparing the two versions, combing through each line for meaning, continuity, and fluidity. Our goal is to present a work that, we feel, helps alter the shape of the early American canon, that argues further for the multilingual roots of what would later become part of the United States, and that documents the difficult attempts to understand events in a new world that cut across imperial boundaries, religious and linguistic differences, and, of course, an ocean.

❧ Obra nvevamente compvesta, en la qual se cuẽta, la felice victoria que Dios por su infinita bondad y misericordia, fue seruido de dar, al Illustre señor Pedro Melendez, Almirante y Capitan de la gouernacion de la mar, de las Indias, y Adelãtado de la Florida.

❧ A newly composed work, which recounts the happy victory that God, in His infinite goodness and mercy, was pleased to give to the illustrious señor Pedro Meléndez,[i] Admiral and Captain of the government of the seas, of the Indies, and Adelantado of la Florida.

Contra Ivan Ribao de na [sic] nacion Frances. Con otros mil Luteranos, a los quales passo à filo de espada, cõ otras curiosidades que pone el auctor, de las viuiendas de los Indios dela Florida, y sus naturales fayciones. Cõpuesta en verso Castellano, por Bartholome de Flores, natural de Malaga y vezino de Cordoua.

Against Juan Ribao of the French nation, with another thousand Lutherans who met the blade of the sword, and with other curiosities provided by the author, on the dwellings of Indians of

la Florida, and their natural features.

[ii] Written in Castilian verse by Bartolomé de Flores, a native of Málaga and resident of Córdoba.

❧ Comiẽça la obra,

❧ Inuocacion.

Emperador de la gloria

Dios poderoso clemente

haz profunda mi memoria

porque con tu gracia cuente

vna tan alta victoria,

Y vos virgen soberana

despertad mi lengua ruda

pues por vos la gẽte humana

tuuo redempcion y ayuda

del daño de la mançana.

Y a mi torpe entẽdimiẽto

ofuscado en negra bruma

dad claridad, y a mi pluma

porque diga lo que siento

desta nueua en breue suma,

❧ The Work Begins,

❧ Invocation.

Emperor of all glory,

Merciful and Powerful God,

grant my memory profundity

so that, by your Grace,

I may tell of a high victory.

And you, the sovereign Virgin,

awaken my crude tongue,

because through you all humanity

has received help and redemption

from the damning apple.

And to my slow understanding

now obscured in black fog,

grant clarity, so this pen

may recount shortly, in brief,

my feelings about this news,

❧ Comiença.

Despues q̃ el rey sinsegũdo

de la Española nacion

gouierna con discrecion

la region del nueuo muudo [sic]

descubierta por Colon.

Embio segun se halla

Naos de armada de Seuilla

para mejor descubrilla

y regilla y conquistalla

con la gente de Castilla.

❧ It Begins.

Ever since the peerless

king of the Spanish nation

governed with discretion

that part of the New World

discovered by Columbus,

he sent, as can be seen,

an armada from Sevilla

for its greater discovery,

conquest and government

by the people of Castilla.

❧ Prouincias ganadas.

Do con animo y pujança

con semblante denodado

la mayor parte han ganado

hiriendo a punta de lança

con coraçon esforçado

Y haziendo a nuestra grey

esta nacion Indiana

de la gente Mexicana

se conquisto por el Rey

la Veracruz y Hauana.

Siguiendo de aquesta vez

la victoria y buen estrena

gano luego a Cartagena

el fuerte Martin Cortes

a Perù con sancta Elena.

Nombre de Dios, y Hõduras

gano luego y la Dorada

a Pamplona la nombrada

las Amazonas y alturas

del Gran reyno de Granada.

Otras prouincias mayores

Españoles subjetaron

do gran riqueza hallaron

mas nuestros conquistadores

la Florida no ganaron.

Que los Indios dela tierra

despues de ser muy ligeros

son indomitos y arteros

y truecan paz por la guerra

porque son grãdes flecheros.

❧ Provinces Won.Where with courage, powerand with bold countenance,

through valiant hearts

and the point of the spear,

the greater part has been won,

and this Indian nation

of Mexican people,

was added to our flock,

Veracruz and Havana were

conquered in the King’s name.

Following that periodof victory and great gifts,

[iii]the mighty Martín Cortés

[iv]then won Cartagena, and through

Santa Elena,

[v] he took Peru.

Nombre de Dios and Honduras

were next won and La Dorada,

then to the famed Pamplona,

to the Amazon and the heights

of the great Kingdom of Granada.

Other greater provinceswere made subjects of the Spaniards,

where they found great riches,

but our conquistadors

could not take

la Florida.

For the Indians of that land,

besides being very agile,

are indomitable and artful,

and because they are great archers,

they trade peace for war.

❧ Como salto en tierra.

Dexando pues esto a parte

de su viuienda y hechura

recontara mi escriptura

de la batalla vna parte

lo de mas de su natura

A veynte del mes de Enero

Pedro Melendez llego

a la Florida y salto

en tierra, y el buen guerrero

su gente desembarco.

❧ How He Reached Land.Leaving aside, then, the restof their life and qualities,

my words will recount

but one part of their nature,

that being the battle.

On the twentieth of January

Pedro Meléndez arrived

in Florida, made landfall,

[vi]and there the good warrior

made his people disembark.

❧ Como vino Iuani.

Do mando luego hazer

alarde de sus Soldados

do todos fueron juntados

para vencer el poder

delos Indios esforçados.

Y estando cabe la mar

con toda su compañia

contra los nuestro venia

Iuani, y empeço a hablar

Francia Francia, en este dia.

❧ How Juani Arrived.[vii]The governor next ordereda muster of his soldiers,

who gathered in formation

to defeat the force

of valiant Indians.

And close by the sea,

with all his company

against ours came Juani,

who had started this day

saying France, France.

❧ Como los metio por vn valle.

La qual razon entendio

el capitan san Vicente

donde luego al continente

el gran Iuani lo metio

por vn valle con su gente.

Veynte y tres millas corrierõ

los Christianos como digo

con aspero desabrigo

y en poco tiempo se vieron

con Iuan Ribao su enemigo.

❧ How He Led Them through a Valley.

The captain San Vicente

then understood who was

nearby on the continent,

the great Juani led him through

a valley with his people.

These Christians, as I said,

ran twenty-three miles,

raw and without cover,

and shortly found themselves

with their enemy, Juan Ribao.

❧ Como los nuestros mataron dos centinelas.

Luego la lengua Iuani

reconocio los paueses

y los luzientes arneses

y a los nuestros dixo ansi

veys a do estan los Franceses

Luego con gran vigilancia

los nuestros ponen sus velas

y encendidas sus candelas

delos Ereges de Francia

mataron dos centinelas.

❧ How Our Soldiers Killed Two Sentinels.

Then the interpreter Juani

spied the pavises, the shields,

and the glowing armor

and he said to our men,

do you see the Frenchmen?

Then with great reverence

our men took their candles

and lit their fuses,

killing two of the French

heretic sentinels.

❧ Como quemarõ el fuerte.

Con esta buena suerte

los nuestros encuentrã luego

y el timulto pueblo ciego

paso dolorosa muerte

con mil maneras de fuego.

su murallon de faxina

quemo nuestros Adelantado

dexando despedaçado

el fuerte y su larga mina

de tierraplene cercado.

❧ How They Burned the Fort.With this stroke of luck,our soldiers discovered them,

and wreaked havoc on the blind people,

bringing a painful death

with a thousand licks of flame.

Our

Adelantado burned down

the daubed wood walls,

leaving the fort in pieces

and the long mine

of terreplein besieged.

[viii]

❧ Como mataron treziẽtos.

Fue cosa de grande espãto

ver los Christianos inuitos

matar a quellos malditos

y su muy esquiuo llanto

dando temerarios gritos

Trezientos y treynta y vno

matan sin dalles clemencia

que no valio su potencia

mas seys cientos de consuno

huyeron sin resistencia.

❧ How They Killed Three Hundred.It was a frightful sightto see the unconquered Christians

slaughtering the damned,

with those heretics crying

back in contempt and scorn.

Three hundred and thirty one

were killed without clemency,

[ix]their strength was useless,

and six hundred more fled,

without any opposition.

❧ Como se retiro Iuan Ribao.

Los Españoles christianos

van matando, y van hiriendo

y ellos se van recogiendo

y España Vandalianos

la victoria van siguiendo

Con arcabuzes y lanças

les dauan guerra sangrienta

y porque entendays la cuẽta

enel campo de Matanças

el Iuan Ribao se aposenta.

❧ How Juan Ribao Retreated.The Spanish Christianswent killing, wounding,

and the French began retreating,

and so the vandals of Spain

[x]secured their victory.

With harquebus and lance,

they waged bloody warfare,

and so that you understand the story,

Juan Ribao takes his place

in the

campo de Matanzas.

[xi]

❧ Como le embio vn correo.

Despojado de su arreo

por seguir tal interesse

a Melendez le paresce

embiar luego vn correo

a Iuan Ribao que se diesse,

Diziendole por su carta

que se diesse a sus prisiones

con amorosas razones

y que se rinda y se parta

el con todos sus varones.

❧ How He Sent a Courier.

Taking off his battle gear

to pursue the course

he then thought proper,

Meléndez sent a courier

with a letter to Juan Ribao,

establishing in writing,

on clement terms, that Ribao

should be put in chains

and surrender his position

as well as all his men.

❧ Como pidio vn cofre Iuan Ribao.

Con el mensagero vn paje

a Iuan Ribao embio

y el Frances quando lo vio

toda su fuerça y coraje

en aquel punto perdio.

Sin hazer casi mudança

lenta su fuerça y ardil

quiso ver por su esperança

y perder la confiança

vn su cofre de Marfil.

❧ How Juan Ribao Asked for a Coffer.

A messenger and page

were sent to Juan Ribao,

and when the Frenchman

saw it, he lost all

courage and resolve.

He barely moved a muscle,

ardor and force slackened,

all hope and confidence

were gone, he wanted to see

his own coffer of ivory.

❧ Como se lo llevo sant Vicente.

Do mando que se tornasse

el paje y el mensagero

y que le den lo primero

el cofre, porque entregasse

las armas gente y dinero,

Vista pues tan buena estrena

y el bien que de todo resta

a la conclusion de sexta

Sant Vicente con Villena

lleuaron cofre y repuesta.

❧ How San Vicente Took It to Him.He asked that the pageand the messenger return,

and when they gave Ribao

the coffer, so he could surrender

his arms, his money and men,

it was seen as a good start,

a good sign for the remainder,

and as the noon hour closed,

[xii]San Vicente returned with Villena,

bearing the chest and response.

❧ Como entrego Iuã Riboa, vna cadena oro cõ vna llaue.

Conuertido en triste lloro

los ojos puestos al cielo

lleno de tormento y duelo

saco su cadena de oro

llorando su desconsuelo,

Y dixo pues que los hados

quieren que tan presto acabe

mi Francelini canabe

saquen doze mil ducados

del cofre con esta llaue.

❧ How Juan Ribao Delivered a Gold Chain with a Key.Moved to mournful tears,

crying over his misfortunewith eyes pressed to the sky,

filled with torment and grief,

Ribao removed his golden chain.

And as he declared, the fates

had wanted this sudden end,

my Francelini Canabe,

[xiii]and with this key he drew

twelve thousand ducats from the chest.

❧ Como se entrego cõ la gẽte.

Enel arena arrojo

su cadena tan preciada

y en ella la llaue atada

y sant Vicente allego

para quitalle la espada,

Mirando con buen subjeto

quan pocos le quedan viuos

de sus Luteros esquiuos

con los demas en efecto

vino a darse por captious.

Y al tiẽpo q̃el sol doraua

los dos cuernos con su rayo

a los diez y seys de mayo

el alua se leuantaua

en las montañas de acayo

Con el color de difunto

la vida esta desseando

sospira siempre llorando

viendo en quã pequeño pũto

esta su vida colgando.

❧ How He Surrendered with His People.Onto the sand he threw

his chain and the attached

key, so precious to him,

and San Vicente stepped forward

to strip Ribao of his sword.

Noting rightly how few

of the wild and disdainful

Lutherans remained left,

Ribao surrendered himself

as captive, along with the rest.

And on the sixteenth of May,the morning broke, with the golden

rays of the sun splitting

the two horns of Taurus

over the mountains of Acaea.

[xiv]The color of a corpse,

still longing for life,

Ribao cried with each breath,

recognizing the tiny point

upon which his life now hung.

❧ La orden que se tuuo para matallos.

El general Vizcayno

manda que ninguno aguarde

porque cerraua la tarde

y en vn hermoso camino

hizo de todos alarde,

Y el adelantado ensaya

lo que bien le satisfaze

que sant Vicente cerrasse

en haziendo el vna raya

con Ribao, y lo matasse.

❧ The Order He Had to Kill Them.

The Biscayne general

ordered that none delay,

the afternoon was ending,

and a handsome path was made

by the men stationed on display.

And the Adelantado declared

it would satisfy his will

for San Vicente to finish

the deed with a stripe

on Ribao, killing him.

❧ Como matarõ seys ciẽtos.

Todos por este concierto

en hordenança passaron

y la señal denotaron

en conclusion q̃ muy cierto

a los seyscientos mataron,

Todos dizen viua el rey

y la fe del redemptor

y Iuan Ribao con dolor

dixo alli memento mei

misericordia señor.

Alli quedo concluyda

la defensa Luterana

y por la gente Christiana

el reyno dela Florida

y sancta yglesia Romana,

con su poder fulminante

Dios cũple nuestros desseos

haga fiestas y torneos

nuestra yglesia militante

con tan subidos tropheos.

❧ How They Killed Six Hundred.Everyone was in agreement,the order was sent down,

and when the sign was given,

in short, it was determined

that they kill the six hundred.

They repeated, long live the King

and the faith of the Redeemer,

and Juan Ribao, in anguish,

recited there his

memento mei[xv]pleading his Father for mercy.

And so the Lutheran defensesin the kingdom of Florida

were brought to an end

by the Christian people

and the All Powerful

holy Roman church.

As God grants our wishes

with such fine trophies,

our triumphant, martial church

holds tourneys and feasts.

❧ Aqui se tratan las grandezas de la rierra [sic] de la Florida.

Y por dar mejor auiso

quiero contar la grandeza

la hermosura y belleza

deste fertil parayso

su gente y naturaleza,

Es vn nueuo mundo lleno

de deleytes y frescuras

con muy diuersas pinturas

prado florido y ameno

con aues de mil hechuras.

❧ Here Is Treated the Grandeur of the Land of la Florida.

And to give better notice

I wish to recount the beauty,

the loveliness and grandeur

of this fertile paradise,

its people and nature.

It is a new world filled

with delights, fresh breezes

and varied painterly scenes,

graced with fields and flowers,

and birds of a thousand kinds.

❧ De vn Rio.

Animales diferentes

Tunas, Palmas, y Higueras,

Auellanos, y Nogueras,

cinco maneras de gentes

y frutas del mil maneras.

Ya segun mi pluma toca

de tan altas marauillas

son cosas dignas de oyllas

que ay vn rio que de boca

tiene quatrocientas millas.

❧ Of a River.Animals of all types,palms, figs, and prickly pear,

walnut and hazelnut trees,

fruits of a thousand kinds,

and five races of people.

[xvi]Now my quill will sing

of such lofty marvels,

things worthy of hearing,

[xvii]including a river that runs

four hundred miles to its mouth.

❧ Gentes de nueue codos.

Y nauegando su altura

cosa digna de contar

puedo por cierto affirmar

tener su legua de anchura

tres mil leguas de la mar

Y en la parte Ocidental

viue gente tan crescida

de gentilidad vencida

que tienen justo y caual

nueue codos por medida.

❧ People Nine Cubits High.And sailing its length,a thing worthy to recount,

I can affirm with certainty

that it is one league wide

three thousand leagues

from the sea.

And in the western parts,

there lives a conquered

pagan people who exactly

stand nine cubits high.

[xviii]

❧ Satriba, y Autina, reyes.

Esta tierra no consiente

enfermedad ni dolencia

ni reyna concupiciencia

de partes del Oriente

esta la nueua Valencia

Aqui reyna Satriba,

con Doresta su muger

el qual tiene tal poder

que el poderoso Autina

jamas lo puede vencer.

❧ Satriba[xix] and Autina, Kings.This country does not consentto either sickness or pain,

nor does concupiscence reign

as it does in the Orient,

it being the new Valencia.

Here reigns Satriba,

who with his wife Doresta,

has such power that even the mighty Autina

cannot conquer him.

❧ Curucutucu, y Alimacani, Reyes.

Tambien Curucutucu

que nunca tal nombre vi

en tierra de Cuncubi

y en la Mocosa el Bacu,

y el fuerte Limacani,

En armas tan esforçado

era el barbaro y ligero

de rostro espantable y fiero

muy velloso y desbaruado

colorado todo el cuero.

❧ Curucutucu, and Alimacani, Kings.[xx]Also Curucutucu, a nameI had never before seen

in the land of Cuncubi,

and in the Mocosa

el Bacu,

[xxi]and the mighty Limacani.

Courageous in arms

and agile, this barbarian

has a terrifying face

and the hair all plucked

from his red hide.

❧ Sus fayciones y hechura.

Sus cabellos denegridos

en forma de cabellera

cortos por la delantera

por las espaldas tendidos

sus carnes todas de fuera.

Iamas no comio comida

que no fuesse por guisar

marisco, y peces del mar

pan de Casabe molida

y vuas cuesco de palmar.

❧ Their Countenance and Form.Their black hair is styledlike a

cabellera,

[xxii]long and straight in back

but cut short in front,

and their bodies, naked.

[xxiii]Food is never eaten

that was not cooked:

shellfish, fish from the sea,

bread ground from cassava

and grape-like seeds of palms.

❧ Natura de arboles.

Vn arbol grande y florido

en aquesta tierra esta

que ninguna fruta da

el qual es atribuydo

en rama y gusto, al Manna.

Es arbol de tanta prez

este, que los Indios tienen

que de muchas partes vienen

a comprallo en cierto mes

que solo del se mantienen.

Otro arbol nasce aqui

que esta verde de contino

de la hechura de Pino

do sacan el Menjuy

y el Estoraque mas fino,

Vn arbol llamado Taca

ay en las Indias de España

del vno cogen con maña

la fina Tacamahaca

y del otro, la Caraña.

❧ Types of Trees.In that country thereis a large, florid tree

that bears no fruit

but is likened to manna

for its appearance and taste.

It is a tree so prized

that Indians from all parts

come to make purchases

during a certain month,

living on this tree alone.

Another tree that grows here

is a type of evergreen,

a pine from which they tap

the aromatic Benjamin,

and the finest storax.

[xxiv]In the Spanish Indies

there is a

taca tree,

from which people skillfully

collect the pure

tacahamaca,

and from the other,

caraña.

[xxv]

❧ Manera de hombres que comen carne humana.

Otros barbaros mayores

de condicion inhumana

ay en tierra de Hauana

que passan a los açores

para comer carne humana.

Otras maneras de hombres

ay dos mil leguas a tras

que jamas viuen en paz

que no se llaman por nõbres

sino baylando de tras.

El reyno de Parica

con el reyno, de Chiri,

la playa de Concubi,

tambien la mar de Arica,

y el gran reyno de Quibi.

Los reynos de Yucatan

con tierra de Patagones

el Brasil, y los Marones,

vencio nuestro capitan,

tambien los Merediones.

La prouincia de Acuti

y el puerto de Chirinagua,

y el cabo de Muloragua

la tierra de Potosi

la ciudad de Nicaragua.

A Ialisco, y Topira,

la nueua Francia Nebrola

Panuco, y el puerto Mola,

Sancta Marta, y Papira,

Cancas, y la Fuen Iirola.

Chichamaga, y tãbiẽ quito

gano y el rio Serrano,

y enel Sur de Magallano,

gano segun esta escrito

Abacal, y a Dastalano,

tambien gano a Tacamala

Veneçuela, y Rumagarta

y porque bien se reparta

gano al Cusco, y Guatimala,

y Apanama, y la Tiarta.

Curiosas cosas no cuento [sic]

de animales ni arboledas

cercadas de fuentes ledas

con otras plantas sin cuenta

nardoscinamomos fresnedas

Las faltas me supliran

pues alo que entiendo y creo

quede corto como veo

mas bien se que entenderan

que fue largo mi desseo.

❧ Fin.

❧ The Type of Men Who Eat Human Flesh.

In the country of Havana

are other great barbarians,

people of an inhuman state

who journey to the Azores

to eat human flesh,

and two thousand leagues away

are other types of men

who never live in peace,

who one does not call by name

without dancing backwards.

The Kingdom of Parica

with the kingdom of Chiri,

the shores of Concubí,

also the sea of Arica

and the great kingdom of Quibi.

The kingdoms of the Yucatán,

with the land of Patagonia,

Brazil, and the Marones,

conquered by our captain,

also the Merediones.

The province of Acutí

and the port of Chirinagua,

and the cape of Muloragua,

the country of Potosí,

the city of Nicaragua.

Also, Jalisco and Topira,

New France, Nebrola,

Panuco and the port of Mola,

Santa Marta and Papira,

Cancas and Fuengirola.

Chichamaga and also Quito

he won, and the River Serrano,

to the south of Magellan,

as written, he also won.

Abacal and in Dastalanos,

also victory at Tacamala,

Venezuela and Rumagarta,

and so he might divide the spoils,

he won Cuzco and Guatemala,

and Panamá and Tiara.

Not of curiosities do I tell,

nor of animals nor of trees,

not of lush springs bordered

by other numberless plants,

nor cinnamon, nards, groves of ash.

These concessions are needed,

for as I know and believe,

as I see, this poem is cut short,

though they may understand

my desires run long.

❧ Fin.

❧ Villancico.

A la justa Cortesanos

ganareys joya de gloria

si derribays con victoria

la cisma de Luteranos.

Iuste pues el que quisiere

que la tela es la prudencia

y el cauallo es penitencia

y la justa es porquien muere

y la espada es la memoria

de la fe delos christianos

Para ganar la victoria

delos falsos Luteranos.

De fortaleza es la lança

y el espaldar de virtud

la Celada es de salud

y el Escudo es temperança

y el titulo dela hystoria

es fuerça de nuestras manos

Para vencer con victoria

la cisma de Luteranos.

La joya del vencedor

del que mejor ha justado

es Christo crucificado

bien del triste peccador

por donde la vanagloria

de los Luteros vfanos

destruye Dios con victoria

a fuerça de los Christianos.

❧ Villancico.

To the joust, Courtiers,

to receive the jewel of glory

if you topple with victory

the Lutheran schism.

Joust, then, he who longs

for the flag that is prudence

and the steed that is penitence,

the joust is for he who dies,

and the sword is the memory

of the faith of the Christians,

securing victory

over false Lutherans.

Of fortitude is the lance,

and the shoulder piece virtue

and the helmet our health,

and the shield temperance,

and the title of the story

is the force of our hands

vanquishing with victory

the Lutheran schism.

The victor’s jewel,

for he who jousts best,

is the sad sinner’s balm,

the crucified Christ,

for where proud Lutherans

once made vainglorious boasts,

vengeful God is now victorious

through Christian force.

❧ Laus Deo. ❧

❧ Laus Deo. ❧

❧ Fue impressa en Seuilla en casa de Hernando Diaz impressor de libros, a la calle de la Sierpe. Año de mil y quinientos y setenta y vno.

❧ Printed in Seville in the house of Hernando Díaz printer of books, on Sierpe Street. The year of one thousand and five hundred and seventy and one.

❧ Con licencia del Illustre señor, el Licenciado Alonso Caceres de Rueda, Teniente dela Iusticia de Seuilla y su tierra por su Magestad.

❧ With license from the Illustrious gentleman, the Licentiate Alonso Cáceres de Rueda, Deputy of the Justice in Seville and its land for his Majesty.

Notes

[i] señor: Less a general title like mister and more an honorific implying master or gentleman.

[ii] The terms viuiendas (viviendas) and fayciones (faiciones) illustrate the variable and changing language of the sixteenth century found throughout the poem. They are noted here as typical examples. Viviendas generally means “dwellings” but has a now obsolete meaning of “modo de vivir” or “manner of living.” And a review of dictionaries from the sixteenth through the early eighteenth centuries available online through the Real Academia Española’s Nuevo tesoro lexicográfico de la lengua española shows no standard way of writing or printing the word, not only the exchange of u’s for medial v’s, but also the exchange of b’s for initial v’s—vivienda, viuienda, bivienda, and biuienda all being found as main entries. Similarly, faiciones comes in several variant spellings (fayciones, faciones, settling in modern Spanish as facciones) and with several possible definitions, from factions to facial features to manners or customs (Nuevo tesoro lexicográfico de la lengua española). There is even an interesting 1604 Spanish-French dictionary entry by Jean Pallet that brings together vivienda and facción, “biuienda, Vie, façon de viure” or “vivienda, See, manner of living [i.e., the now obsolete meaning of facción].”

[iii] estrena: A handsel or gift given for good luck at the start of a new year or new endeavor; according to Covarrubias, the gift recognizes the relationship between vassal and señor, between client and patron, etc.

[iv] A puzzling reference. Hernán Cortés, credited as the Spanish conqueror of Mexico, had two sons named Martín (one legitimate, the other illegitimate); neither participated in the conquest of Peru.

[v] Santa Elena: Most likely Punta Santa Elena in modern-day Ecuador. The other locations in this stanza are locations in South America, mainly in modern-day Colombia.

[vi] Here and elsewhere, Flores has the dates for events in la Florida wrong. Menendez landed and proclaimed the founding of San Augustín on September 8, 1565.

[vii] Juani: Juani appears to refer to Jean François, a mutineer from Fort Caroline (San Mateo), who figures largely in Solís de Merás biography of Menéndez, the Memorial. In Hakluyt’s English translation of Laudonnière, the same man is called Francis Jean and is described as “a traitor to his nation,” being “one of the mariners which stoale away my barkes, & had guided & conducted [the] Spaniards thither.”

[viii] larga mina / de tierraplene: A mina, or mine, is a tunnel dug under a fortification to destroy it with explosives; in this context, however, mina may be a mistake, with a moat, or foso, being meant.

[ix] There was a custom in medieval and early modern European warfare up to the mid-seventeenth century to ask for ransoms in exchange for high value captives taken in battle.

[x] Vandalianos: Natives of Andalucía, a region sometimes known poetically as Vandalia because the Vandals once ruled there.

[xi] campo de Matanças: Literally, field of slaughter, but also where the French were killed, near today’s Matanzas River or Inlet.

[xii] a la conclusión de sexta: The sixth, or noon, hour of prayer; the origin of the word siesta, or nap.

[xiii] Francelini Canabe: Unidentified; possibly an aside to a specific reader.

[xiv] los dos cuernos . . . montañas de acayo: May 16 falls within the astrological sign of Taurus, the Bull, thus the sun “breaking with two horns,” with acayo being the mountain of Achaea, Greece. Flores misdates Ribao’s surrender, which occurred on October 11, 1565.

[xv] memento mei: Remember me. A reference to Luke 23:42: “[A]nd he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom” (KJV).

[xvi] cinco maneras de gentes: Literally, five manners or kinds of people.

[xvii] oyllas: Translated as oir las.

[xviii] nueve codos por medidad: A codo, or cubit, is the length from one’s elbow to the end of one’s finger, making these people of western Florida about thirteen feet tall in Flores’s description.

[xix] Here and below, a misspelling of Saturiba, a sixteenth-century Timucuan; without the letter u, neither line is octosyllabic.

[xx] Alimacani (also Limacani): A Timucuan village on Fort George Island, near present-day Jacksonville.

[xxi] Mocosa el Bacu: The Mocoso were a tribe on the east coast of Tampa Bay and Mocoso was the name of the tribe’s leader; el Bacu is an unclear reference or modifier for Mocoso/a.

[xxii] Sus cabellos denegridos / en forma de caballera: Their hair styled like a caballera most likely means a shock of hair in back, a ponytail, or a wig, the latter which was just coming into vogue by the late sixteenth century but would not be popular until the seventeenth century.

[xxiii] sus carnes todas de fuera: Covarrubias defines “estar en carnes” as going naked, suggesting a pun on food, carne meaning flesh, both as meat and nudity.

[xxiv] Menjuy and Estoraque: Menjuy is also called benjuí, meaning Benjamin or gum benzoin. Estoraque is storax, also called styrax. Both are fragrant gums or resins coming from Asian trees of the genus styrax, used in medicines and perfume and often mentioned alongside other aromatic gums such as frankincense.

[xxv] Tacamahaca and Caraña: Tacahamaca is a Nahuatl word; caraña comes from an unidentified Central American native language. Both are aromatic resins coming from trees native to Mexico and Central America and which were believed to have medicinal qualities.

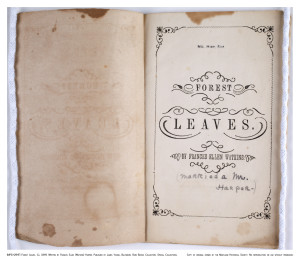

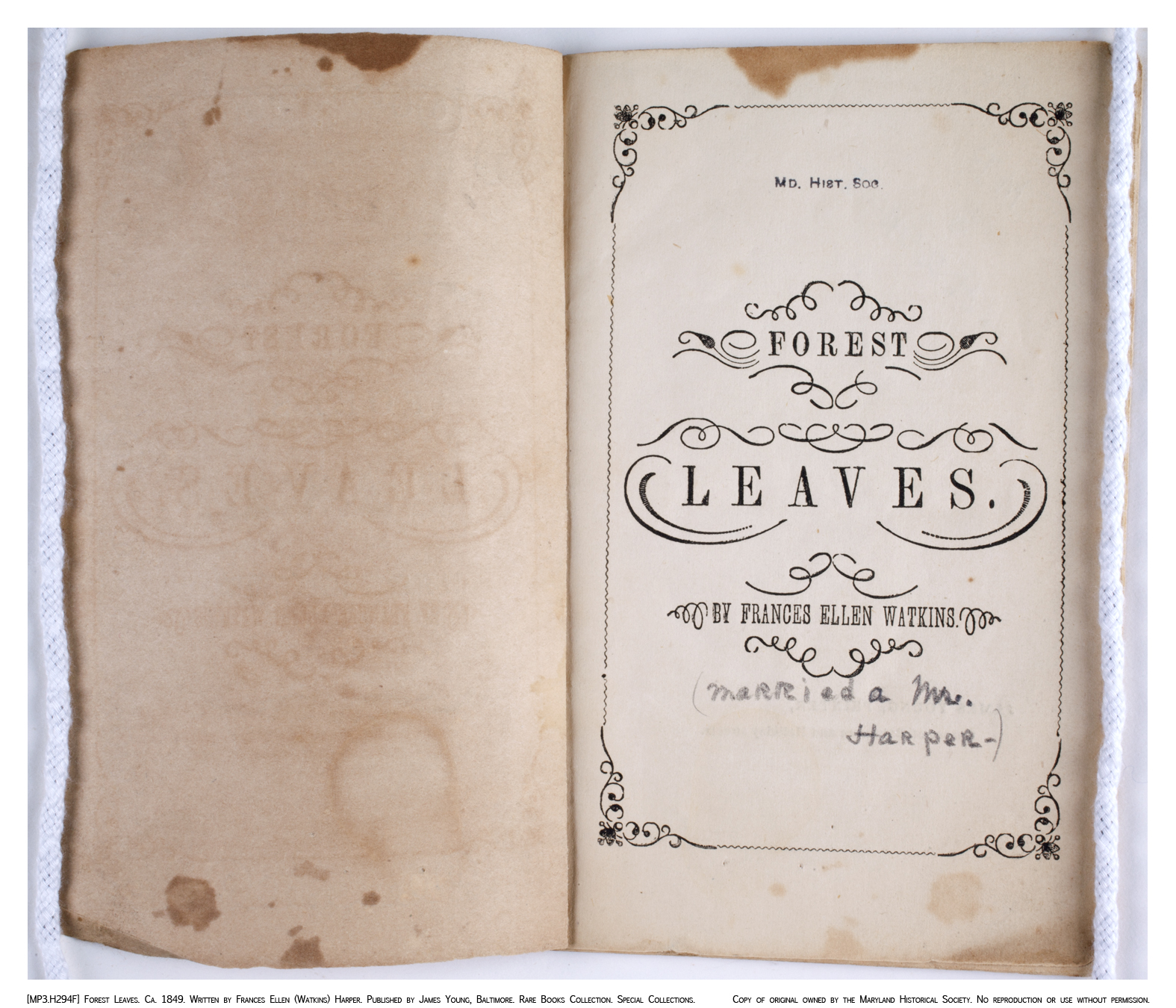

![Title page from Forest Leaves by Frances Ellen Watkins, more commonly known as Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (Baltimore, Maryland, late 1840s). Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, [MP3.H294F].](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/mp3-h294f_01-203x300.jpg)

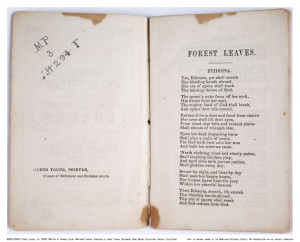

![The first page of Frances Ellen Watkins Harpers’ Forest Leaves. Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, [MP3.H294F].](http://commonplace.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/mp3-h294f_02-300x257.jpg)