Slavery and American Catholicism

or, Please Don’t Accuse Me of Being Theodore Parker Incarnate

Whenever I attend panels or professional conferences that are about religious toleration—such as the wonderful conference the Newport Historical Society recently hosted to mark the 350th anniversary of Rhode Island’s charter (The Spectacle of Toleration)—I am usually struck by the way scholars who don’t specialize in American Catholic history speak about the anti-Catholicism that characterized American life in the nineteenth century.

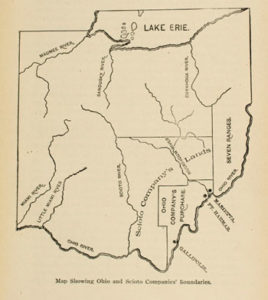

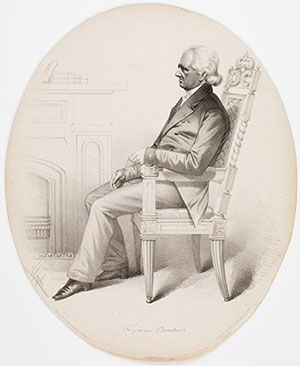

“It was clearly wrong” is the message that is almost always conveyed—implicitly for the most part, but sometimes even overtly. The religious leaders and politicians who railed against the evils of popery and warned of the dire consequences that would develop if immigrants who had been “educated under the despotic governments of Catholic Europe” were allowed to “settle down upon the unoccupied territory of the West” were obviously religious bigots. In the case of ministers like Lyman Beecher and Jedidiah Morse, we’re looking at men whose status at the top of the theological food chain was threatened by Unitarianism and disestablishment, and so they lashed out at the Church of Rome because Catholics were the clearest evidence of the Gomorrah they believed America was slouching towards. In the case of mayors like Philadelphia’s Robert Conrad and Boston’s Jerome V.C. Smith, we’re looking at men whose status at the top of the political food chain was threatened by an influx of immigrant Catholic voters into the Democratic party’s ranks, and so they leveraged the anti-slavery sentiment in their cities and got their supporters to the polls by emphasizing long-standing, Protestant associations between Catholicism and slavery.

Rarely at these conferences does anyone give serious consideration to the possibility that people like Morse, Beecher, Conrad, and Smith might actually have been correct—not in the extremity of their paranoia, of course, but in their basic insistence that there was something a little bit incompatible between the mindset of pre-Vatican II Catholics and the understanding that most Americans had in the nineteenth century of what freedom was and how it ought to operate on the individual soul or voter.

Is it any wonder that American Catholic thinkers have drawn upon W.E.B. Dubois’ idea of “twoness” to describe the “unreconciled strivings” that come with being an American and a Catholic?

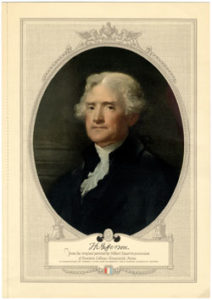

What is curious about this unwillingness of non-specialists in American Catholic history to entertain the possibility that nineteenth-century anti-Catholicism might have been rooted in something real is that historians who focus on the American Catholic experience have acknowledged for many years now that there was (and to some extent still is) a fundamental tension between “American” and “Catholic” values. Granted, polemicists like George Weigel and Michael Novak would have us believe that there is a seamless philosophical and even theological line running from “Thomas Aquinas to [the Italian Jesuit] Robert Bellarmine to the Anglican divine, Richard Hooker; then from Hooker to John Locke to Thomas Jefferson.” In an essay kicking off the American Catholic bishops’ campaign against the Affordable Care Act in 2012, Weigel insisted that the United States owes more to Catholics for its tradition of religious liberty “than the Sage of Monticello likely ever knew.”

But among those writers on Catholicism who have been motivated by a desire to engage with a faithful rendering of the past (rather than a desire to use history to dismantle the signature legislative achievement of a Democratic president), the consensus is that American Catholics have been animated, in historian Jay Dolan’s words, by “two very diverse traditions,” one exemplified by “Thomas Aquinas and Ignatius of Loyola,” and the other exemplified by “Jefferson and Lincoln.”

Dolan has been joined by John McGreevy, Jim O’Toole, Mark Massa, and others in acknowledging that—to quote Massa —”in the history of Western Christianity, there have been two distinctive (and to some extent, opposing) conceptual languages that have shaped how Christians understand God and themselves.” The first language—which shapes the world of people who have been raised as Catholics, American or otherwise—”utilizes things we know to understand things we don’t know, including and especially God.” The Church, in this language, becomes an incarnation of Jesus—its community and the doctrines and hierarchies that govern that community and can be known and experienced by the community’s members become a tangible (dare we even say “fleshy”?) way for Catholics to comprehend God and the salvation that God promises. The mindset that emerges from a language such as this, according to Mark Massa, is one that exhibits a “fundamental trust and confidence in the goodness of … human institutions.”

The second language, utilized by Protestant theologians from Martin Luther and Jean Calvin to Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich, emphasizes the “fact of human estrangement and distance from God.” In this language, it is the Word—the message of judgment and grace, embodied in Christ and found not in the institution of the Church, but in the sanctified lines of Scripture—that convicts the soul, convinces it of its sinfulness, and “prepares us for an internal conversion that makes us true children of God.” The mindset that emerges from language such as this is one that tends to be suspicious of institutions and sees them as distractions that stand between the individual and the Word. Doctrines and hierarchies are “potentially an idolatrous source of overweening pride,” Massa writes; the danger in them is that they are corruptible examples of human beings’ mistaken belief that they can save themselves.

Not all Protestant denominations, of course, have felt the need to jettison the sacramental language that uses the institution of the Church to know and understand God, even as they have embraced an understanding of salvation that sees it as an individual exercise centered entirely upon Scripture. High Church Anglicanism and certain strains of Lutheranism are examples of Protestant denominations that continue to emphasize the idea that the Church—its rituals and traditions—is the embodiment of Christ.

Lutherans and High Church Anglicans, however, did not dominate the political and cultural landscape in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century America. Neither did Roman Catholics. Congregationalists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Unitarians dominated that landscape. And these groups, then—and the staunchly Protestant understanding they had of the relationship between God and humanity, the individual and the community, liberty and authority, and rights and responsibilities—were what shaped American identity during those first few decades that followed independence from Great Britain. Given this reality, is it any wonder that American Catholic thinkers have drawn upon W.E.B. Dubois’ idea of “twoness” to describe the “unreconciled strivings” that come with being an American and a Catholic?

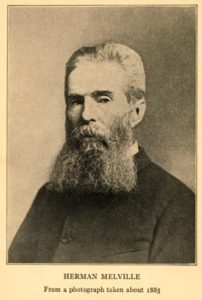

Theodore Parker recognized the unreconciled nature of American and Catholic strivings, and he worried—passionately—that when push came to shove, American Catholics would privilege their respect for hierarchy and authority over any respect for liberty and individual rights that they might have developed during their time in America. Naturally, Parker did not phrase his concerns in quite this way; the outspoken minister from Massachusetts who believed that Unitarianism, of all things, was in need of liberal reform was never one for subtlety. “The Roman Catholic Church … is the natural ally of tyrants and the irreconcilable enemy of freedom,” Parker announced in a sermon that he delivered in Boston in June of 1854. As such, “it hates our free churches, free press, and above all our free schools.”

Abolitionists in Boston were up in arms that summer, thanks to the arrest and trial of the fugitive slave Anthony Burns, who was subsequently returned to his master in Virginia in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Theodore Parker wanted his listeners to understand that they would not be able to count on Boston’s growing Catholic population to support the abolitionist movement. “Individual Catholics in America are inconsistent,” he conceded, and did, occasionally, “favor the progress of mankind.” Such people were “exceptional,” however, as the vast majority of Catholics did whatever their priests told them to do. “The Catholic worshiper is not to think, but to believe and obey,” Parker instructed his Protestant audience. The problem with that prescription was that “the Catholic clergy are on the side of slavery.” The labor system was “an institution thoroughly congenial to them,” and recognizing that slavery was “an ulcer which will eat up the Republic,” Catholic priests and bishops in America sought to “stimulate and foster [slavery] for the ruin of democracy, the deadliest foe of the Roman hierarchy.”

There was some truth to what Parker was saying—as discomfiting as that fact may be to twenty-first-century scholars, steeped as they are in the principles of religious pluralism. As George Weigel’s comments about Aquinas and Jefferson make clear, Catholicism is a faith that prides itself on its conservatism and points proudly to its unbroken, historical and theological connection to the earliest propagators of global Christianity: Peter and Paul, who spoke of the mutually beneficial relationship between a master and his slave; Augustine of Hippo, who insisted that slavery, while not a requirement of Natural Law, was a natural consequence of Original Sin; Thomas Aquinas, who believed that slavery brought order to a fallen world where some people were born without an ability to govern themselves; and St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order that served the Catholic population in colonial and early-national America and was responsible for the church’s early institutional and intellectual development in the United States, who implied that slavery could be a powerful tool in the church’s fight against the spread of Protestantism.

Theodore Parker was not wrong to have observed that Catholicism had constructed a complex understanding of slavery’s necessary role in human relations. Long before evangelical leaders managed to convince Protestant planters that it was fine for them to hold their fellow Christians in bondage (and fine, therefore, for them to allow ministers into the slave quarters to effect evangelical conversions among their bondsmen), Catholics in early eighteenth-century Maryland were having their slaves baptized—and then burying them years later in cemeteries that also held the remains of white Catholics. They were designating their slaves as godparents to their own, white children and arranging for priests to oversee slave marriages, even though slaves were not legally allowed to marry in the colony. There was nothing about the Catholic understanding of human existence, in other words, that suggested slavery was incompatible with the will of God.

Even Pope Gregory XVI’s 1839 condemnation of the international slave trade, In Supremo Apostolatus, stopped short of calling for the emancipation of people who were already enslaved. This was not an oversight, according to Charleston’s Bishop John England. Yes, the papal letter referred to human trafficking as “inhumane commerce” and admonished “all believers in Christ” to not “unjustly … reduce to slavery Indians, Blacks, and other such peoples.” But Gregory’s use of the words “unjustly” and “reduce”—in Latin, injuste and redigere—was not accidental, England wrote to Secretary of State John Forsyth, who had previously served as the governor of Georgia. It meant that Pope Gregory was not condemning slavery as it was practiced in the United States; after all, no one in America was “reducing those who were previously free into slavery” anymore.

Theodore Parker’s mistake was not his observation that there was something “congenial” about Catholicism’s relationship with slavery, even or especially slavery in the United States. His mistake was his conviction that Catholics thought of slavery as an “ulcer” that would “eat up the Republic,” and that they supported slavery, therefore, as part of their plan to bring about the “ruin of democracy.” In fact, quite the opposite may have been true.

Historian John McGreevy has pressed modern-day Catholics to accept that the support lent to slavery by Catholic leaders such as Philadelphia’s Bishop Francis Kenrick and Augustin Martin, bishop of Natchitoches, Louisiana, was more than just an angry response to the anti-Catholic tenor of the abolitionist movement. Answering the question of why “so few Catholics … became abolitionists,” McGreevy tells us, “requires consideration of the divide separating liberals from Catholics during much of the nineteenth century.” Catholics had a “wariness about liberal individualism,” seeing it as a source of “social disorder.” This wariness, McGreevy writes, helps to explain why they were “predisposed … to resist pleas for immediate emancipation.”

But the divide between nineteenth-century Catholics and the liberal individualism that defined American identity did more than simply cause Catholics to resist the idea of immediate emancipation. It also made them deeply dependent upon the institution of slavery for their understanding—and, more important, their acceptance—of the republican foundation upon which America’s political culture was built. This foundation was, in many respects, anathema to Catholicism. In the words of Father Joseph Mobberly, a Jesuit who was born in Maryland in 1779, it was “a brother to the great protestant principle that … ‘every man has a right to read and interpret the Scriptures, and consequently, to form his religion on them according to his own notion.'” It’s not that there were no rights within Catholicism; it’s not that there was no freedom. True freedom, however—at least for a Catholic—was not the purview of the individual, the way it was for an American. True freedom could be found only within the community and with the assistance of the leadership of the Church.

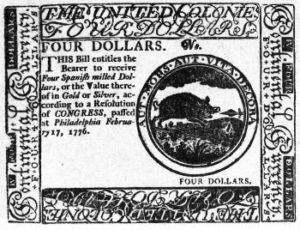

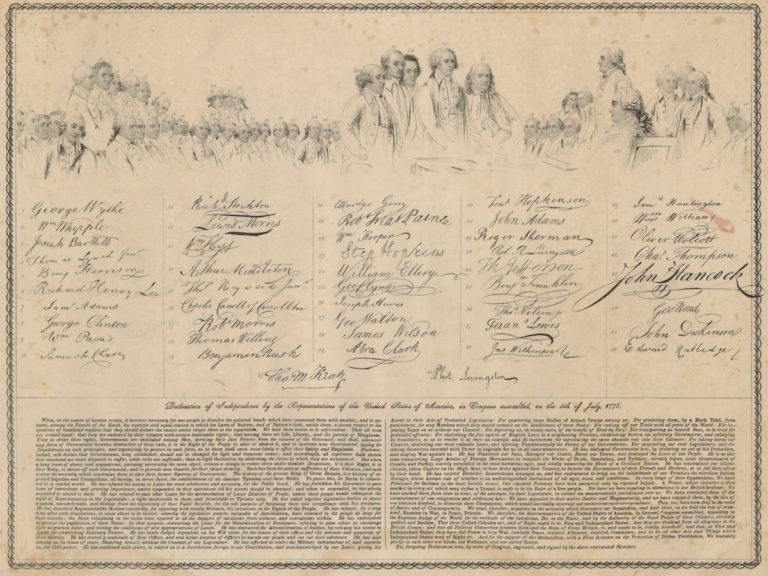

Yet, support for the independence movement in colonial America—a liberal movement that emphasized individual freedom and promised republican government—was greater among Catholics than it was among Protestants, except, perhaps, for the Protestants living in Massachusetts and Virginia. In the late eighteenth century, Maryland was home to the vast majority of English-speaking Catholics in British North America. Men there such as Henry Neale, Luke Mattingly, and Ignatius Combs enlisted in the Continental Army and served on Committees of Safety, even as Catholic leaders in Europe, such as Father Arthur O’Leary of Ireland, condemned the war as a “sedition” that would almost certainly “exclude [them] from the kingdom of Heaven.” Ignatius Fenwick, John Dent, and Thomas Semmes helped to draft a new constitution for Maryland as Charles Carroll of Carrollton signed the Declaration of Independence and Thomas Sim Lee, a prominent Catholic convert, ran for and won the governor’s seat in the free state of Maryland before the war was even over.

An astounding 79 percent of the 145 Catholic men who married in St. Mary’s County between 1767 and 1784 swore their allegiance to the free state of Maryland, donated money and supplies to the American war effort, and served in the Continental Army or the St. Mary’s County Militia. Fifty-eight percent of the men who belonged to the Jesuits’ congregation at St. Inigoes Manor in 1768 did the same, and an analysis of the lives of more than 2,000 men from St. Mary’s County who aided the independence movement reveals that more than half of them were probably Catholic, at a time when the Catholic population of St. Mary’s County was between 25 and 32 percent.

In contrast, the most generous estimates argue that just 40 to 45 percent of the white population in all thirteen colonies actively supported the independence movement—and that average includes Massachusetts and Virginia, where support for the Revolution may have been as high as 60 percent. Maryland was home to one of the largest contingents of loyalist soldiers, and Maryland’s merchants were among the last to sign onto the colonial non-importation agreement in the wake of the Stamp Act. Protestants in the colony, in other words, seem to have been ambivalent about independence; that ambivalence, however, was not shared by their Catholic neighbors.

This willingness to challenge traditional authority and to insist on a right to determine the course of some of the affairs governing their lives continued among America’s first Catholics in the decades that followed the American Revolution. In 1786, the members of New York City’s first Catholic parish insisted on the right to choose their priest and determine his salary as a part of the parish’s founding. Five years later, Catholics in Kentucky wanted their priest, Stephen Badin, to provide them with a constitution—an idea that Badin resisted, but one that Bishop John England proved willing to implement in South Carolina and Georgia just three years after his arrival in Charleston in 1820. In 1818, the members of one, tiny Catholic parish in Richmond, Virginia, were so dissatisfied with their indecipherable French priest that they wrote to Thomas Jefferson, pleading with him to use his political influence to pass a federal law that would require the congregational election of all pastors in the United States, regardless of denomination. Their effort failed to move Jefferson, but it testifies to the strongly republican tenor of Catholicism in early America.

Scholars who specialize in American Catholic history have traditionally pointed to what the celebrated British observer of early American culture, Harriet Martineau, called “the spirit of the time” when seeking to comprehend this fiercely republican period in the American church’s development. The period was more or less over by the mid-nineteenth century, brought to an end by the combination of an influx of Irish immigrants—who tended to exhibit a more deferential or “ultramontane” approach to their church’s hierarchy—and a coordinated effort on the part of America’s bishops to stymie what they believed was a “scandalous insubordination toward lawful pastors” and an “evil that tends to ruin the Catholic discipline to schism and heresy.”

Nevertheless, for the first few decades of the Catholic Church’s development in the new United States, lay Catholics were “influenced by broader American notions of authority,” according to historian Jim O’Toole. They were “accustomed to the republican idea that ordinary people such as themselves were the source of power in civil society,” and they assumed, then, that that meant they were the source of at least some power within the Catholic Church, as well.

Undoubtedly, early American Catholics were influenced by the broader American notions of authority that animated their time. This explanation for the Catholic republicanism that characterized the early national period has many merits. The church’s weak infrastructure during the early years of the republic also played a role. John Carroll, the first bishop of the United States, understood that because there were few priests in the country—and virtually no episcopal framework—the Catholic Church was dependent upon the laity for its survival. Carroll had a love-hate relationship with this dependence. As a member of the Society of Jesus, which had been disbanded by Pope Clement XIV in 1773, he felt no particular obligation to advance the Vatican’s authority among Catholics in the United States. Nevertheless, Carroll was a Catholic—which meant he understood the Church and its hierarchy to be the incarnation of Christ. As such, he found some of the laity’s efforts to exert control over their priests to be examples of “libertinism and irreligion,” and he worked, therefore, to increase the number of priests ministering in the United States and to create an episcopal framework for the country.

John Carroll, in many respects, exemplifies why a narrative that points simply to the “spirit of the times” when explaining Catholic republicanism is insufficient. He was a native-born American who supported the independence movement and even traveled to Canada at one point on behalf of the Continental Congress, in an effort to convince the Catholic residents of Montreal to join the Patriots’ movement. He extolled the merits of the First Amendment in public, even though the Vatican would not formally endorse an individual right to religious liberty until 1965. Carroll promised the members of New York’s first parish that he would “extend a proper regard” to their claim that they were entitled to a voice in “the mode of the presentation and election [of pastors].” But even as he promised New York’s Catholics that he would give them this regard, he fretted that they were acting “nearly in the same manner as the Congregational Presbyterians of your neighboring New England states.”

Carroll, in other words, took the “conceptual language” of Catholicism seriously, even as he embraced America’s political culture. He had a “fundamental trust and confidence in the goodness of … human institutions,” and like all Catholics, he believed there was something a little bit dangerous (a.k.a. “Protestant”) about the radical individualism that characterized American life. Catholics’ disproportionate support for the independence movement and their republican approach to the issue of church governance obscures the reality that America’s first Catholics were not a people who challenged authority easily. This does not mean that they were the patsies their Protestant contemporaries often made them out to be; to be Catholic anywhere in the English-speaking world in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, after all, constituted a challenge to authority on some level. Catholicism, however, embraces hierarchy as something that is necessary in a fallen world, and it teaches that institutions, rightly formed, are mechanisms through which humanity can come to know God. To be Catholic, therefore, has always been to accept the goodness of boundaries that define relationships in terms of order and obligation. Why, then, were the Catholics who initiated and then oversaw America’s transformation from a collection of British colonies to an autonomous republic willing to challenge the authority of their church and their king?

The answer may have something to do with the reality that the republicanism these Catholics embraced was formulated in a slaveholding context.

When the United States was founded, most of America’s Catholics lived in communities where slavery was the foundation of the economy and the framework onto which all social relations were built. In the eighteenth century, the Chesapeake Bay region was home to the second-largest concentration of slave labor in the burgeoning British Empire. Only the sugar colonies in the Caribbean relied on slavery more. In 1790, when the first formal census of Maryland’s population was taken by the United States’ government, roughly a third of the state’s entire population was enslaved. The majority of these slaves belonged to “elite” planters, whom historians define as landowners whose personal estate was worth more than £650 by the mid-eighteenth century. Among these elite planters, Catholics seem to have been the ones who owned the largest number of people.

Between 1743 and 1759, the average number of slaves owned by an elite planter in Maryland was 22; in contrast, the average number of slaves owned by a Catholic—elite or clerical—during this same period was 31. Some Catholic owners had a relatively small number of slaves; Father Joseph Mosley, for instance, reported to his sister in 1766 that he had just “some Negroes” living with him on his eastern-shore farm. Other Catholics were among the largest slaveholders in the colony. Charles Carroll of Annapolis, for example, had 386 slaves living on his four western-shore estates in 1773. His father, Charles Carroll the Settler, owned 112 people at the time of his death in 1720. When Henry Darnall died in 1711, he had 100 slaves living on his estate in Prince George’s County.

Catholics owned more slaves than Protestants did, not because slavery was more attractive to them as members of the Roman Catholic faith, but because they tended to be the colony’s wealthiest residents. This wealth was a consequence of the recusancy laws that had governed the lives of their Catholic ancestors in early-modern England. By the mid-seventeenth century, England’s Catholics were more affluent than their Protestant countrymen, partly because the Society of Jesus had deliberately targeted gentry families when attempting to sustain Catholicism, illegally, throughout the Elizabethan period, and partly because wealthy families were the ones who could most afford to pay the recusancy fines that James I levied against anyone who failed to attend Anglican worship services during his reign.

These wealthy, English Catholics came early to Maryland, a colony that had been founded in 1634 by a Catholic nobleman. They brought their wealth with them and augmented it, then, with the tobacco harvests they were able to reap from the large tracts of land they received in exchange for the indentured servants they brought to the colony. By 1758, ten of the colony’s twenty largest estates belonged to Catholics, although Maryland’s governor estimated that Catholics were just seven percent of the white population.

The world that America’s first Catholics lived in, therefore, was similar to the world that historian Edmund Morgan’s “most ardent American republicans”—i.e., colonial Virginians—lived in. The republicanism that Catholics embraced, consequently, was not built on a foundation of individualism (or, increasingly, anti-Catholicism), the way it was for northern Protestants like Jedidiah Morse and Lyman Beecher. Catholic republicanism—like the southern, “herrenvolk” republicanism that Ed Morgan, Gene Genovese, and Lacy Ford have all identified—was a racialized republicanism, built on a foundation of ordered relationships that were defined and defended by the institution of race-based slavery.

Republican society for southerners and early-national Catholics alike was not one in which freedom and individualism ran amok, the way they did in The Planter’s Northern Bride, an 1854 novel by Caroline Lee Hentz, whose depiction of the horrors of the industrializing North was at least as accurate as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s rendering of the brutality of the slaveholding South. For Catholics and southerners, republican society , at least rhetorically, was one in which communal obligations were honored and relationships were ordered in such a way as to allow for the basic, human needs of all individuals to be met, while at the same time giving a growing number of men—white men—the freedom to cultivate their individual talents.

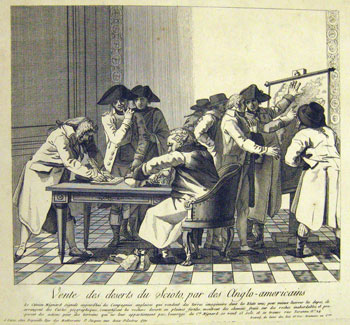

This “positive good” argument for slavery gained traction in the South in the 1820s and ’30s, primarily as a defensive response to the controversy over the Missouri Compromise and the fear that Nat Turner’s Rebellion provoked in 1831. Its roots, however, can be found in the earlier responses of southerners like Parson Weems and Timothy Ford to the French Revolution and the efforts of yeoman farmers in South Carolina to expand their representation in the state’s legislature by not allowing low-country planters to count their slaves when determining district apportionment. Weems insisted that the sans culottes misunderstood “equality,” since the condition, properly speaking, was a matter only of “equal dignity … in appropriate station.” Ford believed, self-servingly, that slaves should be counted in the process of apportionment because slavery helped societies realize the liberal ideal. “In the country where personal freedom and the principles of equality were carried to the greatest extent ever known,” he wrote in 1794, referring to ancient Sparta, “domestic slavery was the most common, and under the least restraint.”

The reality of race-based slavery and the rhetoric that planters increasingly used to justify it made republicanism and individual freedom “safe” for early-American Catholics to embrace by ensuring that the bonds of hierarchy and reciprocal obligation that were so important to the Catholic understanding of human relations remained intact. America’s first Catholics did not worry that what one late-nineteenth-century priest disparagingly referred to as “the principle of private judgment” would “produce disruption in civil as well as in religious society.” Early American Catholics—not just the laity, but even some clergy, like Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore and Bishop John England of Charleston—believed that they could challenge lawful authority, even to the point of waging war, and it would not lead to “exaggerated fanaticism” or “render government impossible, unless by brute force.” They believed they could do this, because even as they challenged authority, America’s first Catholics did so in a context that had clearly defined boundaries of prerogative and duty.

To say that slavery played a role in the making of an early-American Catholic identity is not to say that America’s first Catholics were “slavish.” It is also not to agree with Theodore Parker that Catholicism was or is an “irreconcilable enemy of freedom.” The argument does not even require us to accept that Catholics could not have embraced the republican tenets of American identity without the mitigating influence of slavery. The Irish Catholic newspaper editor Matthew Carey, after all, became a staunch advocate of republicanism after he arrived in Philadelphia in 1784, at a time when slaves made up less than one percent of Pennsylvania’s population. As Edmund Morgan wrote with regard to his fiery Virginians: “This is not to say that a belief in republican equality had to rest on slavery, but only that in Virginia (and probably other southern colonies) it did.”

Matthew Carey aside, the fact is that America’s first Catholics did, by and large, embrace republicanism in a slaveholding context, and we will never know if Charles Carroll, Ignatius Fenwick, or Thomas Sim Lee would have accepted the ideology at the heart of the American Revolution without the reality of race-based slavery. What we do know is that the only active, Catholic loyalists in the colonies were not from Maryland; the “Roman Catholic Volunteers” were a group of around 200 Catholics from Pennsylvania who, unlike their religious brethren to the south, did not encounter the freewheeling, individualistic qualities of republicanism in a slave-holding context.

We also know that in the years that followed the American Revolution, as non-slaveholding alternatives to lived republicanism became available to white southerners—thanks in large part to a deliberate easing of manumission laws in the Upper South—Catholics eschewed these alternatives, even as some of their Protestant neighbors chose to accept them. This Catholic unwillingness to see slavery as incompatible with individual freedom may have been a consequence of the fact that the slaveholding context in which Catholics embraced the tenets of American identity made republicanism less radical—and therefore more palatable—to a group of people whose religious worldview had clearly defined boundaries of authority and obligation.

In the seven years that followed the end of the Revolutionary War, between 7,000 and 10,000 slaves in Maryland were freed by their masters—a phenomenal spike in manumissions that scholars have pointed to as a sign that some slaveholding members of America’s founding generation recognized that slavery could not be easily reconciled with the ideology of the American Revolution. Few, if any, of these manumitting masters seem to have been Catholic.

Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Edward Fenwick (Ignatius’ son), and Thomas Sim Lee did consider releasing some of their slaves from bondage—but not until well into the nineteenth century. Carroll, who died in 1832, made arrangements in his will to free one slave, Bill, out of the more than 300 people he owned. He also manumitted seven slaves in 1808 who claimed to be descended from a free white woman, Nell Butler, and were already suing for their freedom. Thomas Sim Lee manumitted one of his slaves, Nell, and all of her children in June of 1815. The woman’s name suggests that she, too, may have claimed an ancestral connection to Nell Butler, as quite a few slaves in Maryland did. Edward Fenwick promised in 1825 to let his slave Michael purchase his freedom for $318. By 1830, Michael had paid Fenwick $218, and he had found a man named Gardiner who was willing to provide the remaining $100. Fenwick agreed to release Michael after he had worked for Gardiner for three years. In 1833, however, when Gardiner petitioned for Michael’s release, Edward Fenwick refused.

In 1790, the Catholic strongholds of St. Mary’s, Charles, and Prince George’s counties had the highest free-black-to-slave ratios in all of Maryland. In Prince George’s County, the ratio of free black to enslaved was 1 to 68, meaning that 99 percent of the people of African ancestry in Prince George’s County were enslaved. In contrast, the heavily Calvinist Anne Arundel County had a free-black-to-enslaved ratio of 1 to 13. Planters in both counties cultivated tobacco, a very labor-intensive product. Yet, in spite of the need for labor, in Anne Arundel County, more than 7 percent of the black population enjoyed a modicum of freedom.

Much to the frustration of historians, very few manumission papers actually list the slaveholders’ reasons for freeing their slaves. That being said, several records from Maryland in the 1780s and 90s—the brief period after the war that saw a spike in manumissions—do point to the belief that slavery violated “the inalienable rights of Mankind,” or that a slave was entitled to the “free enjoyment of his rights and liberty.” It is noteworthy, therefore, that none of the records after 1802 point to these principles when explaining a manumission. While some slaveholding Americans may have been keenly aware of the disconnect between their property and their principles in the aftermath of the American Revolution, that awareness seems to have worn off as time marched on, and historians believe that the slave manumissions that occurred in the nineteenth century, then—that is to say, the period when Catholics tended to manumit their slaves—were motivated by other factors, such as the declining profitability of slavery in the Upper South.

None of this information requires that Catholics be condemned as a group for failing to manumit their slaves in the immediate wake of the American Revolution. The truth is that most Methodists, Anglicans, and Calvinists did not free their slaves during this period, either. But some did. And the fact that Catholics did not suggests that they may not have seen the hierarchical and authoritarian reality of slavery as inconsistent with the republican principles they embraced when they became Americans.

In this respect, then, Theodore Parker ought not to be dismissed as a religious bigot, simply because he frequently observed that he “never knew of a Catholic … who favored freedom in America.” Parker probably didn’t ever meet or read about a Catholic who embraced freedom as he—a liberal Unitarian—understood it. Freedom, for him, was something wholly and completely individual; it manifested itself most clearly in the “personal self-rule of modern times.” Theodore Parker never spoke of the U.S. Constitution as an example of “well-regulated republicanism,” the way Bishop John England of Charleston did; he never lauded the American system as one that embodied “the conservative principle of freedom” that respected “the spirit of the community …without such a spirit, and such precautions, no true liberty can exist.” That’s because Theodore Parker didn’t share John England’s very Catholic belief that republicanism needed to be “regulated” or reined in by anything other than individual virtue.

It is probably still true that the politicians and religious leaders who railed against Catholicism in the first half of the nineteenth century were motivated by a certain degree of status anxiety—some, perhaps, such as Lyman Beecher, more than others. But it is also true that these leaders were motivated by a real sense that the Catholic understanding of freedom was different from theirs, and they were right to see Catholics’ support of the institution of slavery as the embodiment of this difference. Freedom, for Catholics, was corporate; it was born of the “reciprocal duties” that one priest from colonial Maryland insisted all people had to one another. Freedom, for Catholics, was not “personal,” the way it was for Protestants like Theodore Parker.

It is no small irony, therefore, that modern-day Catholics like Bishop William Lori of Baltimore have been appealing to personal freedom in their attempt to protect the collective freedom of the Catholic Church from the mandates of a law that supporters say defines healthcare as a “requirement of a free life that the community has an obligation to provide.” In 2012, on the eve of the Church’s first “Fortnight for Freedom”—a now annual event that highlights “government coercions against conscience” such as the birth control provision in the Affordable Care Act—Lori made his reasons for opposing the healthcare overhaul clear: “If we fail to defend the rights of individuals,” he warned, “the freedom of institutions will be at risk.”

It was an assertion that—could he have heard it—might have confounded Mr. Parker, or at the very least given him pause.

Further Reading:

For more on the differences between a Catholic and a Protestant mindset—and the challenges, then, that those differences posed for Catholic assimilation into American culture—see: Jay Dolan, In Search of an American Catholicism: A History of Religion and Culture in Tension (New York, 2002); Mark S. Massa, Anti-Catholicism in America: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (New York, 2003); John T. McGreevy, Catholicism and American Freedom (New York, 2003); and James M. O’Toole, The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America (Cambridge, Mass., 2008).

For more on traditionalist Catholic claims to religious liberty and the recent “Fortnight for Freedom” movement sponsored by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops see: Michael Novak,“The Return of the Catholic Whig,” First Things, March 1990; George Weigel, “‘Fortnight for Freedom’: U.S. Catholics and Religious Liberty: The Origins,” First Things, June 20, 2012; Melinda Henneberger, “Is the Catholic ‘Fortnight for Freedom’ really a ‘Fortnight to Defeat Barak Obama?’” op-ed, Washington Post, June 7, 2012; Rich Daly, “What the 112th Congress Faces,”National Catholic Register, January 21, 2011.

Theodore Parker’s comments about the link between Catholicism and slavery can be found in his essay “The Rights of Man in America” (1854) in The Rights of Man in America, F.B. Sanborn, ed. (Boston, 1911). Bishop John England’s interpretation of In Supremo Apostolatus can be found in his letter to Secretary of State John Forsyth, September 29, 1840, in Letters of the Late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth, rpt. (Independence, Ky., 2012).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3 (Spring, 2015).

Maura Jane Farrelly is associate professor of American Studies at Brandeis University, where she directs the Journalism Program. Before joining Brandeis, she worked as a full-time reporter in Atlanta, Washington, D.C., and New York. Farrelly is the author of Papist Patriots: The Making of an American Catholic Identity (2012).

!["Ch[arles] Carroll of Carrollton," lithograph by Albert Newsam after the painting by Thomas Sully, published by Childs & Inman Lithographers (Philadelphia, 1832). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](http://commonplace.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/15.3-Farrelly-6-214x300.jpg)

![Elizabeth Whitman's headstone, on the left, damaged by relic seekers, as it has appeared since the late nineteenth century. The new stone, at the right, was installed by the Peabody Historical Commission and Peabody Institute Library in 2004 and mimics the design of Eliza Wharton's headstone in Hannah Webster Foster's The Coquette. Photo courtesy of the Salem News, Salem, Massachusetts. [The photo was used in an article on 24 July 2007]](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/9.3.Waterman.1-300x245.jpg)