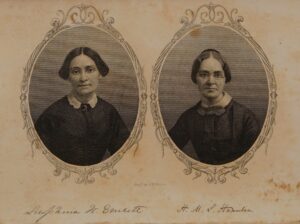

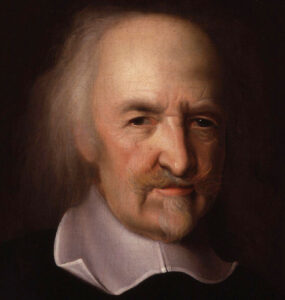

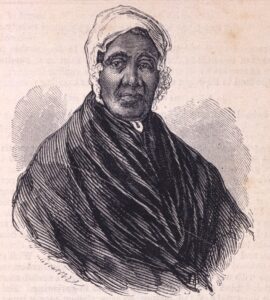

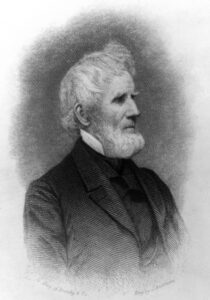

For their part, Graham’s son-in-law and daughter didn’t mention the women’s relationship in the biographies they crafted of Graham at all. One reason for the silence may be because the family told a selective story about Graham and slavery, presenting her as a slaveholder with moral qualms about slavery. New research in original documents has turned up more enslaved people in Graham’s life than the family revealed and likewise raises questions—possibly irresolvable—about the story her daughter Joanna Bethune, who was firmly antislavery, told about her mother’s views. Graham’s son-in-law also had a nephew who was a “colored lad.” Perhaps sensitivity about that relationship was another reason the family avoided a story about an interracial partnership, even one involving religious friendship. As sectional tensions over slavery rose, newer editions of Graham’s biographies cut out references to Graham’s reported opposition to slavery. Critics of the change charged Graham’s grandson, the Rev. George Bethune, with trying to “conciliat[e] slaveholders with silence upon the evils of slavery. By 1860, when George Bethune came to write a memoir of his mother, Joanna Bethune, he credited her with being “The Mother of Sabbath-schools in America.” “[T]he facts and dates,” he insisted, “show that Providence intended for Mrs. Bethune the distinction” birthing the Sunday school movement in the United States. Joanna Bethune, an influential philanthropist in her own right and indeed a key leader of the Sunday school movement, had long been in her mother’s shadow and now her son wanted to put her in the limelight. There was no room in this origins story for a formerly enslaved Black woman.

Hailed by some and ignored by others, in both cases because of the politics of race, Ferguson and Graham’s unlikely cooperation to spiritually educate underserved children was one dimension of each woman’s role as a founding philanthropist.

The Widows Society was fading by the mid-1900s. But one of its spinoffs, a child welfare agency originally known as the Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York and now known as Graham Windham, remains in operation today and has been supported by the cast and crew of Hamilton: An American Musical. Over two centuries after Ferguson and Graham, separately and to some degree together, cared for New York’s vulnerable children, Graham Windham has a Black women president, Kimberly Watson, an ordained minister.

Further Reading

Anne M. Boylan, “Benevolence and Antislavery Activity among African American Women in New York and Boston, 1820-1840,” in Jean Fagan Yellin and John Van Horne, eds., The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994).

Anne M. Boylan, The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797-1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

Bettye Collier-Thomas, Jesus, Jobs, and Justice: African American Women and Religion (New York: Knopf, 2010).

Jane E. Dabel, “‘I Have Gone Quietly to Work for the Support of My Three Children’: African-American Mothers in New York City, 1827-1877,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 27 (no. 2, 2003).

Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Allen Hartvik, “Catherine Ferguson: Black Founder of a Sunday School,” Negro History Bulletin 35 (no. 8, 1972): 176-77.

Robert J. Swan, “John Teasman: African-American Educator and the Emergence of Community in Early Black New York City, 1787-1815,” Journal of the Early Republic 12 (no. 3, 1992): 331-56.

Kyle B. Roberts, Evangelical Gotham: Religion and the Making of New York City, 1783-1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Margaret Washington, “Going ‘Where They Dare Not Follow’: Race, Religion, and Sojourner Truth’s Early Interracial Reform,” Journal of African American History 98 (no. 1, 2013): 48-71.

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century accounts of Ferguson and Graham include:

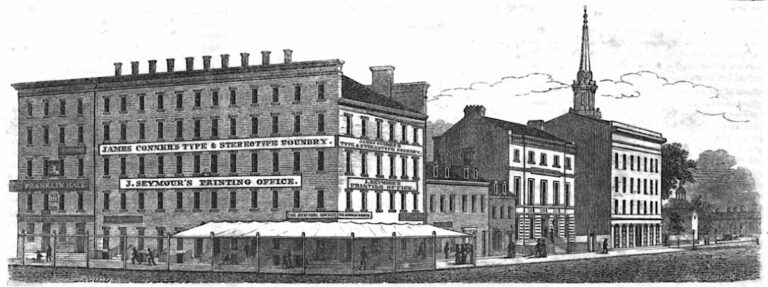

[Divie Bethune], The Power of Faith Exemplified in the Life and Writings of the Late Mrs. Isabella Graham (New York: J. Seymour, 1816).

[Joanna Bethune], The Power of Faith, Exemplified in the Life and Writings of the Late Mrs. Isabella Graham. A New Edition. Enriched by Her Narrative of Her Husband’s Death and Other Select Correspondence (New York: American Tract Society, 1843).

Joanna Bethune, The Unpublished Letters and Correspondence of Mrs. Isabella Graham: From the Year 1767 to 1814; Exhibiting Her Religious Character in the Different Relations of Life (New York: Theological and Sunday School Bookseller, 1838).

Memoirs of Mrs. Joanna Bethune, by her Son, the Rev. George W. Bethune, D.D. With an Appendix, Containing Extracts from the Writings of Mrs. Bethune (New York: Harper Brothers, 1863).

“Catherine Ferguson” in “City Items” section, New-York Daily Tribune, July 20, 1854. This obituary was republished, in modified form, in various antislavery and evangelical periodicals. Later in the century, writers retold the story in religious periodicals. See, for example, “Katy Ferguson,” New York Evangelist 62:5 (January 29, 1891).

Mrs. John W. Olcott, “Recollections of Katy Ferguson” in The Southern Workman 52 (1923): 463.

Primary sources on Ferguson include:

“For the Commercial Advertiser,” New-York Spectator, July 14, 1821.

“The donations for the slave Jack, amount to $937 50,” New York Journal of Commerce, August 27, 1835.

See also listings for Catherine Ferguson in the Longworth’s New York City Directories from 1814-1850 (available digitally from the New York Public Library).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Modupe Labode, Crystal Moten, Kyle Roberts, and Sarah Jones Weicksel for helpful conversations about Ferguson and Graham.

This article was originally published in August 2022.

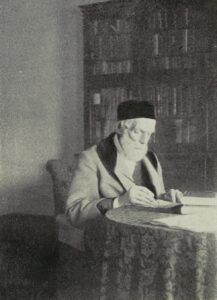

Amanda B. Moniz, Ph.D., is the David M. Rubenstein Curator of Philanthropy at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Her book, From Empire to Humanity: The American Revolution and the Origins of Humanitarianism, was awarded ARNOVA’S inaugural Peter Dobkin Hall History of Philanthropy Book Prize. She is currently working on a biography of Isabella Graham.