Big Money Comes to Boston

The curious history of the Pine Tree Shilling

According to the 1652 act of the General Court that authorized the creation of the Massachusetts mint, the coins were supposed to be square.

“for forme flatt & square on the sides & Stamped on the one side with N E & on the other side with xiid. vid & iiidaccording to the value of each peece together with a privie marke which Shalbe appoynted every three monethes by the governor & knowne only to him & the sworne officers of the mint.”

In other words, Massachusetts would issue square coins, without pictorial design or embellishment, nothing but the letters N E (for New England) on one side and their value in Roman numerals on the other. Each coin would bear a secret mark, changed every few months at the governor’s discretion, to assure the public that the money was trustworthy.

But even as the committee appointed to implement this legislation was just forming, John Hull, the newly named mintmaster, began to undermine the concept of square coins and sketched designs for circular coins in the margins of the committee’s minutes. Before the first coins were minted, the General Court changed its orders and declared that Hull and his assistants “shall Coyne all the mony that they mints in A Round forme till the Gennerrall Corte shall otherwise declare their minds.” Even for Puritans given to iconoclasm, who would never think to put a graven image on their coins, square pegs simply could not fill the round holes that legitimate money occupied in their pockets and imaginations.

Why did the General Court contemplate this deviation from circular custom, and why did the mint committee reject it? An answer lies in the depths of European tradition concerning money and its representation of sovereignty and economic power. In the modern era, money has become nationalized. Each nation-state is expected to have its own exclusive currency. But before the middle of the nineteenth century, the basic division of the world’s moneys lay not along national lines but between what we might call “big money” and “little money.”

Big money was commodity money, money in which the claims about value and quality stamped on a coin’s surface were consistent with its value as a material substance, a sterling silver shilling or a gold florin. Big money was coined by monarchs and states, traded by international traders for expensive commodities in large volumes, and regulated carefully for consistency and stability.

Little money was fiduciary money, money made of an inexpensive and plentiful substance that bore little relation to the value stamped on it. It came in small denominations and was often issued by local authorities, corporations, or associations rather than by states or monarchs. Little money was not well integrated with big-money currencies, often fluctuating wildly in value from place to place or else circulating across narrowly confined geographical areas.

Cowrie shells performed this little-money function in Africa, India, China, and Southeast Asia, the areas linked by the Indian Ocean. Cowries, measured out in bags and bushels, were useful for trade in many different goods over an enormous geographical area, but it was difficult to correlate the fluctuating value of cowries with that of the high-grade gold and silver coins issued by the Mughal of India. In Europe, plentiful cheap metals were more commonly employed for similar purposes. In early seventeenth-century London, more than three thousand different businesses and organizations issued farthing coins of copper, tin, or lead, which circulated within only a few city blocks. Cowrie shells and farthings were prime examples of little money.

Square coins have always been rare, but before the Massachusetts General Court’s flirtation with the idea, square coins seem to have been associated with little money. The 1497 statute of Ferdinand and Isabella, specifying the weight, quality, and design of Spanish silver reales, ordered the coinage of various denominations, including the half-, quarter-, and eighth- real pieces. The whole, half, and quarter coins were to be round, but the smallest coin to be issued, the eighth real, would be square: “e que los ochavos sean quadrados.” Similarly, a description of early English monetary practices in Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577) claimed that “King Edward I did first coine the penie and smallest peeces of siluer roundwise, which before were square.”

Before 1652, Massachusetts had been a little-money economy. The gold and silver coins that some of the early migrants brought from England quickly flowed back across the Atlantic in payment for imported goods. In the absence of a circulating medium, colonists turned to substitutes like wampum and musket balls to conduct their local exchanges. But these forms of fiduciary money did not meet all the needs of the people of Boston, especially the merchants who began to enter the Atlantic trading economy in the 1640s. The General Court’s decision in 1652 to begin coining high-quality silver shillings expressed a desire among the colony’s leaders to move from a little-money to a big-money economy. The initial call for a square coinage may reflect a latent uneasiness about making such a bold move. Perhaps the square design was meant to disguise the fact that Boston was attempting to enter the world of big money by presenting their coins in what was traditionally a small money form. But Hull and his fellow merchants knew better—they were making big money, and big money, commodity money, was supposed to be round.

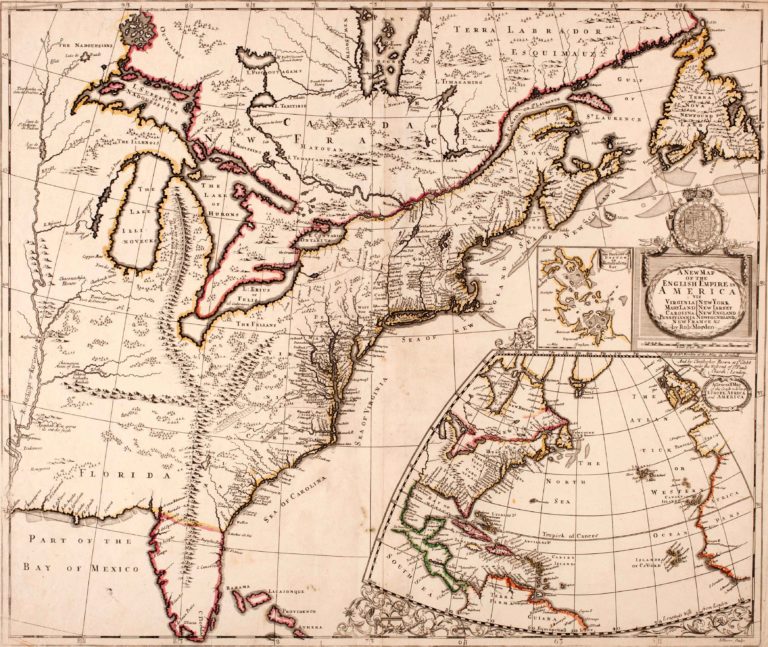

Entering the world of big money meant encountering the challenges of empire. Bostonians would inevitably face consequences for meddling in the affairs of the great imperial powers competing for dominion over the Atlantic world—Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands, England, even Sweden and the native American nations and confederacies that surrounded them. All these constituted threats to the autonomy to which Bostonians believed they were entitled by their founding charter and on which their newfound livelihood depended. Accepting the challenge of empire meant playing the complicated game of maintaining their autonomy in the face of external threats by means of negotiation, alliances, the payment of tribute, the development of mutually beneficial trading relationships, trickery, and if need be, by means of violence and war.

Boston’s move to enter the world of empire grew out of the city’s own modest imperial designs. Boston’s founders and commercial leaders were committed to gaining control over as much of the New England region as possible. To accomplish such a goal, this small, weak, and resource-poor commonwealth had to extend its authority over territory beyond its borders, martial its own meager resources to exploit the material wealth of alien regions, and influence the political economies of other places enough to suit their own needs.

These twin forces of imperial competition and transatlantic commerce presented the greatest challenges to Bostonians’ aspirations in the seventeenth century. Their desire, as a Puritan colony, for autonomy and brotherly interdependence would be severely tested by the incessant reach of empires and by the corrosive power of trade to measure all values in cash. But survival in the Atlantic world required coming to terms with the forces of empire and commerce, and for that reason, Boston had to resolve its money problems and the restricted commercial and political power that its small money signified.

Boston’s ability to dominate the New England region was initially constrained by the severe geographical limitations of its charter. The charter granted Massachusetts only a narrow band of coastline, between the Charles and Merrimac Rivers and a few additional miles on either side. These limits meant that upon settlement, Bostonians found that they had little access to the fur trade because the Charles and Merrimac could be navigated only a short distance into the interior. In addition, the key to the fur trade was wampum, the strung beads made from whelk or clam shells that the Dutch at New Amsterdam had transformed from an item of ritual diplomacy among Indians into a monetary system throughout the region. But the clams needed for wampum production and the Indians with the skill to make it lived only along the coast of Long Island Sound, well beyond the reach of Massachusetts.

To remedy this problem, Bostonians made their first attempt at imperial expansion, a simultaneous effort to hive off new colonies in Connecticut and to assert their dominance over the Pequot and Narragansett Indians who controlled wampum production. Intrusive colonization and blundering diplomacy quickly gave way to aggressive warfare. By 1637, Massachusetts had driven out the Dutch, destroyed the Pequots, and made tributaries of the Narragansetts, Niantics, and Mohegans. Over the course of the next forty years, Boston collected thousands of pounds sterling worth of wampum, enough to subsidize a substantial part of the cost of New England colonization.

In a remarkably short time span, between 1633 and 1637, Bostonians recognized the potential value of wampum and exploited that potential to achieve dominance over extraterritorial lands, to gain access to furs, and to organize political relations among Indians and colonists of the coastal northeast. Yet in subsequent years, in almost as short a period, the value of wampum collapsed. After a decade and more of inflation and devaluation, in 1661 the Massachusetts General Court demonetized wampum, ordering that no one could be forced to accept payment in wampum against their will.

By contrast, the cowrie shell money produced in the Maldive Islands of the Indian Ocean, which became the small money of the West African slave trade, remained relatively stable and reliable for centuries. Wampum seemed to have all the advantageous qualities of cowrie shells—decorative and ceremonial uses, lightweight, durable, uncounterfeitable, and available in large yet still limited supplies. What’s more, European merchants did not have to transport wampum across thousands of miles of ocean or desert to reach the markets where it was most in demand, and they had far greater control over its production and acquisition than the Dutch and English East India Companies had over cowries. So why did wampum fail?

The answer lies in understanding the difficult challenge of integrating local economies and small moneys into international trade and tributary networks. When sixteenth-century Portuguese traders arrived in coastal West Africa, they discovered that cowrie shells, despite their very low denominational value, were already part of an integrated and complex economy that spread across North Africa to the Indian Ocean and beyond. Once the Portuguese found their own source of shells, it was simple to extend that economy a bit further, to use shells to buy slaves for the sugar-producing islands off the African coast that they had recently acquired.

The Dutch and English traders who entered Long Island Sound in the 1620s believed they had found something like cowrie shells, but they were wrong. At the time they first encountered it, wampum was not money—it was a useful item in a native gift economy that was more like diplomacy than commerce. But by mistaking wampum for money, the Dutch monetized it, giving it a value as a currency and expanding the geography of its usage to new places. Still, wampum’s value as a currency was limited primarily to the American Northeast, in particular the regions adjoining the member tribes of the Iroquois League. Its exchange value depended on its value to those groups, the chief suppliers of furs to New England traders.

As Bostonians soon discovered, wampum’s utility as money vanished when it could no longer be relied on to produce furs for export to European markets. By the mid 1640s the fur-bearing animals that could be reached by New England’s rivers were disappearing. At the same time, New England’s expansion into Connecticut and across Long Island Sound in the 1630s, gave New Englanders easier access to wampum. The end result was the collapse of wampum’s value as more and more of this indigenous currency chased fewer and fewer pelts. In the late 1640s, Boston’s merchants dumped as much of their wampum as possible on the Dutch merchants of New Netherlands, who had once taught them its value and from whom they had struggled to wrest it only a decade before.

By the 1640s, as Bostonians began to trade in the West Indies, foreign currency began to wash up in New England, much of it clipped or counterfeit and all of it confusing in terms of value. With wampum’s value in rapid decline, Boston seized this opportunity to coin its own money. The timing of this decision hinged on developments at the opposite pole of the Western hemisphere. Most of the Spanish coins that drifted into Boston were made of silver mined in Potosi, the enormous silver mountain high in the Andes. Pieces of eight minted at Potosi were among the most common coins in early Boston, but at the end of the 1640s, word began to spread through the Atlantic of a scandal. The master of the mint had been issuing debased coinage for over a decade, skimming the difference for his personal profit. The resulting widespread distrust in the Spanish money supply motivated Bostonians to make their own coins.

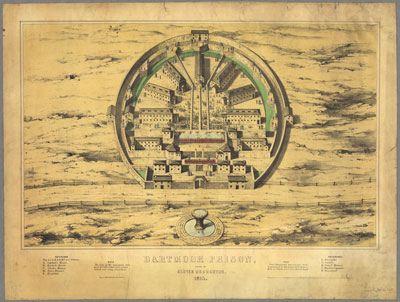

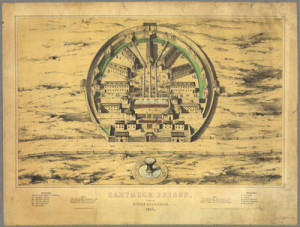

For a colony to coin its own money was to usurp a privilege that monarchs jealously guarded. Of course, in 1652, there was no king in England, and Boston’s mintmaster, John Hull, followed the model of Cromwell’s commonwealth in casting the coinage. Like the Commonwealth shilling, the Massachusetts coins bore no human image, no images at all. But these first coins were so crude and so easily clipped that they were rapidly replaced by a more elaborate design, though still without a human image. These were the so-called Pine Tree Shillings. On the reverse was the date, 1652, the value in Roman numerals, and as a superscription on the two sides of the coin, the words “Masathusets in New England.” John Hull was ordered to produce coins of the same quality alloy as English sterling but only three-quarters the weight of their English equivalents. That is, a Massachusetts shilling was lighter and smaller than an English one, though valued at the same rate within New England. The lighter weight was to insure that Massachusetts currency would stay in Massachusetts, as foreign merchants would be less willing than local ones to accept underweight shillings.

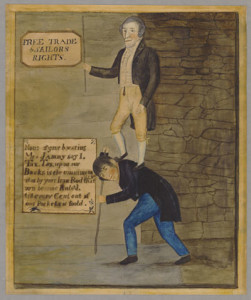

During the years of Oliver Cromwell’s rule, the Massachusetts shillings went unchallenged, but after the Restoration of the monarch in 1660, King Charles II demanded a reckoning of the colony’s conduct. Massachusetts’s interests were represented by Sir Thomas Temple, who had lived and traded in Boston during the 1650s. Charles II questioned Temple closely about the Massachusetts currency, claiming that it was an invasion of his royal prerogative. Temple attempted to explain that the colony was ignorant of the law and had meant no harm in coining money strictly for their own use, and as he explained, he brought out a Massachusetts coin and presented it to the king.

“Charles inquired what tree that was? Sir Thomas informed him it was the royal oak; adding, that the Massachusetts people, not daring to put his majesty’s name on their coin, during the late troubles, had impressed upon it the emblem of the oak which preserved his majesty’s life. This account of the matter put the king into good humor and disposed him to hear what Sir Thomas had to say in their favor, calling them a parcel of honest dogs.”

In this dexterous act of verbal tribute, Temple insisted that Massachusetts had usurped nothing—that, in its coinage, the colony had been honoring the king in a hidden and invisible way. For the moment, the bluff succeeded.

Within a few years, pressure would be renewed when the crown sent a royal commission to investigate the laws of Massachusetts. In May 1665, the commission demanded that the law establishing “a mint house, &c, be repealed, for Coyning is a Royal prerogative.” In response, the General Court neither complied nor sent a representative to London to defend their case. Instead, they offered Charles more tribute: “It is ordered, that ye two very large masts now on board Capt Peirce his ship . . . be presented to his majty . . . as a testimony of loyalty and affection from ye country, & that all charge thereof be paid out of the country treasury . . . ” Meanwhile, they went right on minting their coins.

A decade later, facing another royal commission, Boston’s leadership decided to bluff once more. John Hull, now the colony’s treasurer as well as the mintmaster, consigned aboard his own ship The Blessing a handsome tribute consisting of eighteen hundred and sixty codfish, ten barrels of cranberries and three barrels of samp (high-grade cornmeal mush). Although it seems unlikely that the king accepted these commodities as adequate tribute, from Boston’s point of view, these gestures “worked”—John Hull continued to make Pine Tree Shillings. Only when the colony’s charter was vacated in the 1680s under pressure from James II did the mint stop producing coins.

By the time of its demise, the Pine Tree Shilling had done its appointed task. Massachusetts was now a big-money economy, the port of Boston was the second busiest shipping entrepot in the British empire, and its mercantile community had solidly established ties of credit around the Atlantic world. The notes these relationships produced would become the basis for various experiments in paper money in decades to come. Despite its lack of natural resources, or perhaps because of this very absence, Boston managed to become a thriving port city, an integral part of the Atlantic economy, and the powerful hub of New England, by finding and making money of the appropriate size.

Further Reading:

For a more extensive discussion of the Pine Tree Shilling and its role in Boston’s commercial and diplomatic affairs of the later seventeenth century, see Mark Peterson, “Boston Pays Tribute: Autonomy and Empire in the Atlantic World, 1630-1714,” in Allan Macinnes and Arthur Williamson, eds., Shaping the Stuart World, 1603-1714: The Atlantic Connection (Leiden and Boston, 2006). My discussion of fiduciary and commodity, or “big” and “little,” money relies heavily on Eric Helleiner, The Making of National Money: Territorial Currencies in Historical Perspective (Ithaca, 2003). On pre-modern British money, see John Craig, The Mint: A History of the London Mint from A.D. 287 to 1948 (Cambridge, 1953). On cowrie shells and their distribution in West Africa, see Jan Hogendorn and Marion Johnson, The Shell Money of the Slave Trade (Cambridge, 1986). Excellent discussions of wampum in early New England and its relationship to the Atlantic economy can be found in Lynn Ceci, “Native Wampum as a Peripheral Resource in the Seventeenth-Century World System,” in Laurence M. Hauptmann and James D. Wherry, eds., The Pequots in Southern New England (Norman, Okla., 1990); and in David Murray, Indian Giving: Economies of Power in Indian-White Exchanges (Amherst, Mass., 2000). Detailed information on the early currencies of Massachusetts can be found in Louis Jordan, John Hull, The Mint, and the Economics of Massachusetts Coinage (Hanover, N.H., 2002); and Sylvester Sage Crosby, The Early Coins of America, and the Laws Governing their Issue (Boston, 1875).

This article originally appeared in issue 6.3 (April, 2006).

Mark Peterson teaches in the history department at the University of Iowa. He is the author of The Price of Redemption: The Spiritual Economy of Puritan New England (Stanford, 1997) and is at work on a book on Boston in the Atlantic World.