Picturesque California

How westerners portrayed the West in the age of John Muir

In the late 1880s the far western states were attracting new residents from across the United States and around the world. This was especially true of the largest western state, California, which had joined the union in 1850: by 1880 its population surpassed 860,000 and would grow in the next decade to over 1.2 million—less than Virginia’s but more than Maryland’s, two states that had been absorbing immigrants since the seventeenth century. With several rail lines now completed, many immigrants, as T. S. Van Dyke wrote in Picturesque California, came in “Pullman cars instead of ‘prairie schooners’” and “built fine houses instead of log cabins.” Yet for most Americans, the Far West was still largely unknown. The great exceptions were the region’s prime natural wonders, Yosemite Valley, the giant sequoias, Yellowstone National Park, and the Grand Canyon. Some would have seen oil paintings, stereographs, or photographs of these famous sites, and many more would have seen wood-engraved illustrations in inexpensive periodicals with national circulations.

In 1888, the San Francisco-based publisher James Dewing (ca. 1846-1902) launched a project to provide the most comprehensive visual coverage of the Far West yet available: Picturesque California and the Region West of the Rocky Mountains, from Alaska to Mexico. Edited by John Muir, who wrote much of its text, it was the first major illustrated work on the West produced primarily by westerners. Sold by subscription, the work first appeared serially in thirty parts, with more than eight hundred images produced by an array of printing technologies.

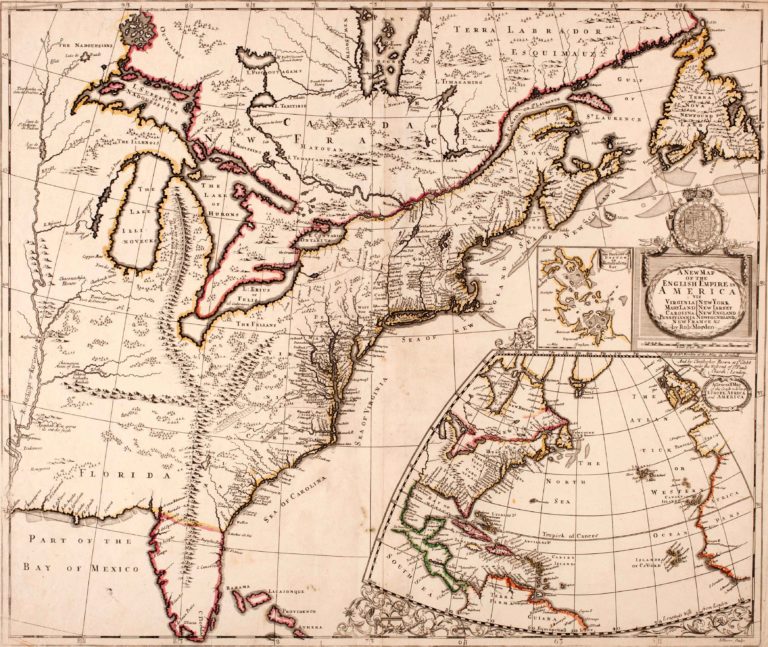

A brief overview of what came before will help us understand Picturesque California’s contribution to the imagery of the West and its place in the history of graphics more generally. In the 1830s and 1840s several works published in Europe depicted the topography and indigenous peoples along the upper Missouri River. Few Americans saw these expensive works and their magnificent large plates—either aquatints or lithographs with hand coloring. They were designed for a wealthy European audience. Following the close of the Mexican War in 1848, when the United States acquired California and other western territory and the Gold Rush was in full swing, the U.S. government sponsored expeditions to explore the newly annexed territories and identify the best railroad routes. These expeditions yielded many volumes containing small lithographs and engravings of the landscape, the inhabitants, the geology, and the flora and fauna of these regions. Such reports were distributed primarily to government officials but sometimes reached a wider public. Interest in the West burgeoned after the Civil War and especially after the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. Popular, inexpensive periodicals, such as Harper’s Weekly, mainly based in New York, sent artists west to make sketches for wood-engraved illustrations, and Currier & Ives and other firms produced inexpensive lithographic views of western scenery and towns.

From 1872 to 1874, New York’s D. Appleton and Company published a work illustrating the scenery and cities of the entire country that was clearly a model for Dewing: Picturesque America, edited by the eminent poet William Cullen Bryant. Other similarities besides the title were the large format, the variety of media—both wood and steel engravings—and the serial publication (forty-eight parts at fifty cents each). But the earlier work covered only a few areas of the West—the San Francisco region and northern California, the Columbia River Valley, Yellowstone National Park, the Colorado Rockies, and the Grand Canyon—and the writers and artists were travelers from the East. Picturesque California’s treatment of the region would be much more comprehensive, and it was published by a San Francisco firm, with text and many images produced by westerners.

James Dewing, originally from Connecticut, had joined his brother in San Francisco after serving in the Union Army. By 1871 he was a partner in Francis Dewing and Company’s publishing firm. After Francis’s death in 1883, James Dewing operated a bookstore and publishing office and with other family members manufactured and sold pianos, organs, and school furniture. In January 1887 the J. Dewing Company was incorporated with a capital stock of $250,000, presumably from investors interested in Picturesque California’s publication. By 1888 the firm had established a New York office, no doubt to help promote the book.

Little is known about Picturesque California’s early genesis. But clearly, Dewing was well enough connected to engage John Muir (1838-1914) as editor and principal writer. Muir was not yet the household name he is today or even the nation’s premier conservationist (he would found the Sierra Club in 1892). Still, he was well known for his expertise on the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the Yosemite Valley, which President Lincoln had made a state park in 1864. An early review of Picturesque California described him as “the man of all others who has most lived with and expressed nature in California.” His articles expounding his theories on Yosemite’s formation and describing the glaciers he had found in the Sierras had appeared in the San Francisco periodical the Overland Monthly from 1872 and in Harper’s and Scribner’s, the nation’s leading illustrated monthly magazines, from 1875 through the 1880s. Dewing’s invitation to edit Picturesque California came at an opportune time for Muir. As a father and principal breadwinner, exploring the Sierras and California’s other natural wonders had become impractical for him. He accepted the commission and reworked some of his earlier articles in preparing his contributions.

Picturesque California was eventually issued in many different formats, at different prices, a marketing tactic popular with publishers of elegant illustrated works. The initial issue was in thirty 16 x 12-inch parts, at one dollar each, distributed monthly. At least part of the printing was done in New York. The December 1888 Overland Monthly described the parts as “laid within grey cloth book-covers, tied with ribbon” and stamped in red with a vignette of the old Carmel Mission and mountains and a pine and palm in the background. The review explained that in more expensive editions many of the illustrations were printed on India paper (a thin, fine-quality paper) and in the most expensive, on satin. The array of boxes and bindings offered is suggested by the entries on Picturesque California in John Muir: A Reading Bibliography. An alternative, longer title was sometimes used: Picturesque California: The Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Slope. California, Oregon, Nevada, Washington, Alaska, Montana, Idaho, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Etc. Eventually, in 1894, less expensive, shorter versions were issued on poorer quality paper, without the plates. The short title, Picturesque California, is in keeping with the work’s focus: of thirty-one separate articles, twenty-one pertain to regions of California, whereas the other areas are covered in one article each, with Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada each receiving only four or five pages (and Idaho none at all).

The title page’s assertion that the work is “Illustrated with Etchings, Photogravures, Wood Engravings, Etc. By Eminent American Artists” is entirely justified. Picturesque California’s illustrations aestheticized the West using all the most popular processes of the moment—following the fashions of the East. In some processes, like etching, the artist created the image on the printing surface, while others, like photogravure and photoengraving used photography to prepare the printing surface. (The technology for printing photographs via the half-tone process was just being developed and was used sparingly in the book.) The etchings, photogravures, and photoetchings constitute the 120 “plates” on heavier paper that are interspersed between every four pages of text. The text paper is coated and lighter weight. At least thirty-seven different artists from across the country contributed to the work, all skilled and some quite well known. Many of the plates featured works of California painters, especially Thomas Hill (1829-1905), who had long painted Yosemite and other scenic regions; William Keith (1838-1911), a friend of his fellow Scotsman John Muir; Julian Rix (1850-1903); and Charles Dormon Robinson (1847-1933).

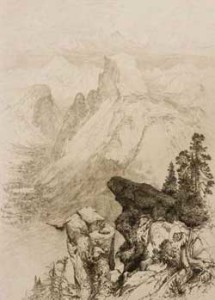

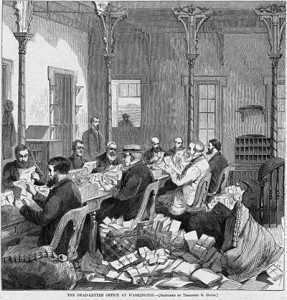

The original etchings, numbering only fifteen among the 120 plates, are some of the most appealing of the book’s illustrations. To prepare an intaglio etching, the artist uses etching needles and other tools to scratch through the ground covering the metal plate and then uses acid to bite the lines he or she has created. The incisions hold the ink and with the pressure of the printing press the ink is absorbed by the paper. The late 1870s and 1880s saw a revival of interest in the centuries-old process in the United States and publishers began including etchings in their most elaborate illustrated books (fig. 1). (The four photoetchings among the book’s plates have less of the artist’s touch.)

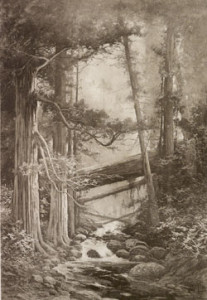

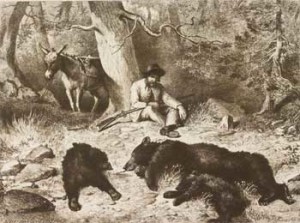

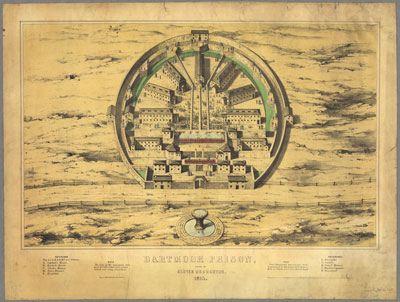

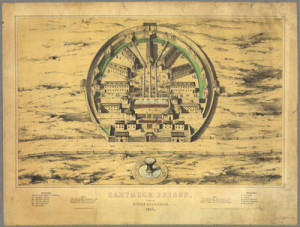

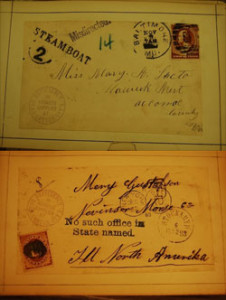

The majority of the plates, 101, are photogravures, a process that was first used in the 1880s to produce high-quality monochrome reproductions of paintings and photographs. It used photography to make intaglio printing plates. The prospectus for Picturesque California claimed that “by means of a new process of photo-gravure . . . the painter’s work is reproduced as in a mirror,” “losing nothing” of the artist’s “individuality” or “style.” Although admired by some at the time, most of the photogravures reproduced landscape paintings characterized by soft textures and little detail, and, without full color, the results are often rather muddy and dull. Photogravure more successfully reproduces photographs or works with distinct details (figs. 2 and 3).

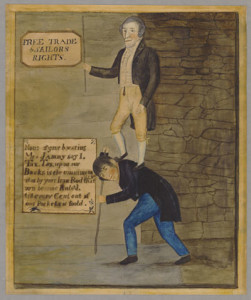

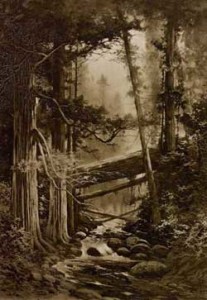

Even more of the illustrations—the seven hundred printed along with the text—were produced either by wood engraving or the newer photoengraving, which could reproduce the artist’s lines through photographic means. Because both utilized a relief printing surface, they could be printed at the same time as letterpress type and were less expensive to produce than plates printed on an intaglio press. Most of the text illustrations are photoengravings; the few wood engravings may be identified by an engraver’s name in addition to the artist’s. Some of the text illustrations faithfully reproduce delicate ink drawings (fig. 4), and many are examples of the still-popular composite approach, with highly irregular shapes and overlapping or interlocking images (fig. 5).

Further novelty was introduced by printing some of the plates and text illustrations in other colors besides the usual black or brown; some were printed entirely in either red, green, blue-gray, or reddish-brown. Picturesque California was initially published before the color half-tone process came to be used, so the publishers chose this unusual means of introducing color.

The writers for Picturesque California were primarily prominent Californians who wrote about areas they knew well. Next to Muir the best known was the colorful Joaquin Miller (1837-1913), whose long poem Song of the Sierras (1871) and subsequent travelogue My Life among the Modocs (1873) purportedly chronicled his California adventures. Others had already written about California: Charles Howard Shinn (1852-1924) had published Mining Camps: A Study in American Frontier Government (1885); George Hamlin Fitch (1852-1915) was the literary critic of the San Francisco Chronicle; T. S. Van Dyke (1840-1923) published Millionaires of a Day (1890), a critique of California real estate speculators; and the widely published naturalist Ernest Ingersoll (1852-1946) had covered Colorado and New Mexico in his The Crest of the Continent (1883).

The primary theme of Picturesque California is a dual one: that these western regions contain both countless natural wonders—surpassing those of the East—and impressive works of civilization. Further, these features make the region a worthy alternative to foreign travel. Indeed, for some of the contributors the natural wonders of the West promised visitors a nearly religious experience. As Muir wrote of the Sierras, “Visions of ineffable beauty and harmony, health and exhilaration of body and soul, and grand foundation lessons in Nature’s eternal love, are the sure reward of every earnest looker in this glorious wilderness.” The illustrations provide images of more peaks, mountain ranges, and waterfalls than had been included in any one publication previously—places both celebrated and unfamiliar. On the other hand, there is little attention to the barren desert regions of the West, which, after all, did not conform to the variety, irregularity, and contrast of the picturesque aesthetic.

The parallel emphasis on advancing civilization, including growing cities, tourist facilities, railroads, and agricultural expansion contains the implicit message that the region’s natural beauty can coexist with population growth and economic development. The writers expect that further amenities will make life in the West comparable to life in the East. In addition, they explain, southern California offers an idyllic environment unique in the United States—a sunny climate year round, with semi-tropical plants, fruits, olives, and vineyards—features that prompted the by-now-familiar comparison to Italy. For example, George Hamlin Fitch claimed of Santa Cruz, “Italy has no place on which the sun rests fairer, where the roses bloom more luxuriously, where the air is so warm and caressing.”

The superlatives throughout the text suggest the authors had two central purposes: on the one hand, to bolster the growing sense of regional pride among westerners and, on the other, to combat persistent notions of a lawless, uncivilized frontier among easterners. Of the brand-new state of Washington, Muir comments that although it is little known to easterners except as “wild west,” its citizens from diverse European backgrounds have put aside “sectarianism” to work there in harmony. John P. Irish implicitly chides those who might denigrate the West by pointing out a wheat field in the irrigated Sacramento Valley nearly twice the size of Rhode Island and worth more than sixteen million dollars, the same amount the federal government paid Mexico in 1848 for California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of Colorado and New Mexico.

With Muir as editor, it is no surprise that mountains—both forbidding and accessible—receive more attention than any other feature of the region. Unlike earlier explorers such as Clarence King who used metaphors of battle to describe his ascents, Muir emphasized the “enduring blessing” and harmonious feelings of such excursions (despite the dangers he frequently encountered). And because many of the great western mountains were accessible, such experiences were not limited to the hardiest climbers. Muir pointed out that the southern Sierras have less ice and snow than the passes of Switzerland, and with the railroad to Sacramento, “everybody with money may go to Mount Shasta, the weak as well as the strong” (figs. 6 and 7).

Images of rock formations, especially Yosemite’s Half Dome and Sentinel, and waterfalls in many regions abound. The West’s vegetation, so different from the East’s, is depicted—from giant redwoods, sugar pines, and Douglas spruce forests to wildflower meadows with “larkspurs eight feet high and lilies with thirty flowers on a single stalk.” But the messages can be contradictory. While Muir stresses the need to protect some of the ancient forests, he is also impressed that the mills of Puget Sound and California “are said to be the largest and most effective lumber-makers in the world.” Attractive images of logging operations contrast with John P. Irish’s charge that using the trees of the Sacramento Valley for lumber is like breaking up Greek statuary “into stones to wall a well or build a sewer.” Similarly, images portray a wealth of animal life in the region, from hummingbirds to bears, and writers emphasize the excellent opportunities for hunting and fishing. For example, Miller praises the tributary waters of the Sacramento as the most favored spot in the world “for rod and gun,” with an abundance of grizzly bears and the world’s largest mountain elk (fig. 8). On the other hand, Muir notes that “tourist sportsmen” and ranchers are driving away the game.

In images the Indians who have lived for centuries in the West are depicted as picturesque elements in the landscape, but the text is more negative. While illustrations show them in traditional food-gathering activities, such as hunting for eggs of gulls and other seabirds (fig. 9), the writers more often view them as annoying intruders. Muir finds the Mono Indians “mostly ugly, or altogether hideous” but is kinder to the Indians of the McCloud River, who have “better features” and are “ambitious in their way.” Whereas Muir hopes for assimilation, Ingersoll is offended by those who disregard “Indian rights or feelings.” Similarly, while the illustrations of San Francisco’s Chinatown feature its picturesque qualities (fig. 10), Miller harshly describes the Chinese as “ugly” and “asleep for thousands of years.”

By 1888, the agricultural potential of the far West was of more interest than its potential for quick mining wealth. The writers praise several different river valleys as the most fertile in the West, and images of orchards and vineyards abound (fig. 11). For example, Jeanne C. Carr boasts that the irrigated fields of “Orange, Santa Ana and Tustin counties contain a greater wealth of products than any other equal portion of the country.”

Picturesque California also depicts the West’s progress in establishing cities and towns with attractive homes and top-quality educational, religious, and scientific institutions. Text and image depict San Francisco’s magnificent bay, which could hold “all the navies of the world,” its cable cars, the new Golden Gate Park, and the “castles” of Nob Hill (fig. 12). Miller calls San Francisco “the New York of the broader and better side of this continent.” Among many other featured cities are Berkeley, with the University of California; Oakland, with “the most perfect ferry service in the world;” Santa Barbara, with “one of the most beautiful sites anywhere;” Denver, the most important city between Chicago and San Francisco; Vancouver, which has grown from a forest clearing in 1885 to a full-fledged seaport of twenty thousand; and Los Angeles, with sixty-five thousand inhabitants occupying about thirty square miles, served by fifteen railroad lines. Revealing the region’s cultural attainments are the new Lick Observatory, with “the greatest telescope in the world,” and the soon-to-be-completed “Cambridge of the west,” Leland Stanford Jr. University in Palo Alto.

A secondary but important theme derives from nostalgia for the region’s Spanish and Mexican past. This is clear, for example, in the admiration for Monterey, with its tile roofs and adobe walls, and nearby Carmel Mission. Fitch suggests a visit there, where “the dreamy Spanish life . . . takes no account of time or progress,” is “equivalent to going abroad without crossing the ocean” (fig. 13). Interest in identifying places associated with Helen Hunt Jackson’s best-selling 1884 novel about southern California, Ramona, also suggests the strength of romantic notions of California’s past, an interest that will fuel the tourist industry in the region.

This brief overview of the 478 pages and over eight hundred illustrations can only give a taste of Picturesque California’s riches. Soon after publication began, in February of 1890, a report to the Literary World (Boston) judged it the most important current “literary enterprise” in San Francisco. Several western newspapers ranked it high nationally.

According to the San Francisco Chronicle it was “one of the finest illustrated works ever produced in this country” and would “give to Eastern readers for the first time a satisfactory idea of the wonderful grandeur, beauty and variety of California scenery” (fig. 14). Some of California’s politicians and academics endorsed it, as did librarians from as far away as Minneapolis and Brooklyn. The San Bernardino Board of Trade thought the fact that it was “free from direct advertising or ‘booming’” would enable it to gain the attention of the “best people throughout the Union,” the type California needed. Similarly the San Jose Mercury expected it would “draw hither many permanent dwellers, which no other form of temptation could reach.”

Such endorsements, which were quoted in the 1894 edition, must have pleased Dewing, but they were evidently not enough to make the work a financial success. By the spring of 1891 Dewing and Company, at least the San Francisco office, had declared bankruptcy. Although the expense of employing so many artists and such elaborate and varied printing processes to depict the West’s variety and magnificence proved greater than the financial return, the publication no doubt played a part in enhancing the self-confidence of westerners and the respect afforded the region in the rest of the country.

Finally, in terms of its graphics, Picturesque California could and would have been produced only at the particular time it was: when artists still played a major role in landscape images in books; when etching was the new artistic craze; when printing of photogravures was a new (and short-lived) technology; when wood engraving was being gradually replaced by photoengraving; and when, although the allure of color was strong, the technology for four-color printing had yet to be worked out. Picturesque California was a most flamboyant example of the last major publications illustrating scenery and cities before photography and mechanization displaced artists and craftspeople.

Further Reading:

John Muir, A Reading Bibliography, compiled by William F. Kimes and Maymie B. Kimes (Palo Alto, Calif., 1977), contains details of many different issues and editions of Picturesque California. Two overviews of images of the West are: Ron Tyler, Prints of the West (Golden, Colo., 1994) and William H. Goetzmann and William N. Goetzmann, The West of the Imagination (New York, 1986). On Picturesque America, see Sue Rainey, Creating Picturesque America: Monument to the Natural and Cultural Landscape (Nashville, 1994). An excellent history of California in the latter half of the nineteenth century is Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (New York, 1973). On Muir, see Linnie Marsh Wolfe, Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir (New York, 1945), Frederick Turner, Rediscovering America: John Muir in His Time and Ours (New York, 1985), and Sally M. Miller, ed., John Muir in Historical Perspective (New York, 1999). Many of the quotations praising Picturesque California appearing in the text were printed on the back of the part covers of the 1894 edition; the San Francisco Public Library owns a set of this edition. The Sierra Club’s Website includes Muir’s contributions to Picturesque California and the prospectus for the original publication, which was printed inside the front cover.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.3 (April, 2007).

Sue Rainey is editor of Imprint: Journal of the American Historical Print Collectors Society and writes about artists who contributed illustrations to books and magazines in the latter half of the nineteenth century.