“None Need Think Their Sympathy Wasted”

Reading early American books

In their introduction to this issue of Common-place, the editors ask why early American books have remained unread outside university English departments, even as nonfiction studies of Revolutionary and early U.S. history and biography have achieved extraordinary popular success. Scholars of early American literature sometimes gaze wistfully at best-selling biographies and award-winning miniseries and wish that some of that limelight would fall on our texts. We’d like others to share our pleasure in early American texts and to appreciate the insights they offer into American culture, or at least to know that American literature begins before The Scarlet Letter. But many early American texts are reaching audiences outside the academy—audiences of religious readers, for whom the texts remain current and spiritually compelling.

Religious presses have long been reprinting texts by early American writers, including both Puritans and Quakers. Amazon.com offers several paperback editions of Jonathan Edwards’s Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, along with one edition for Kindle and three editions of John Woolman’s Journal (fig. 1). On January 12, 2008, three editions of Sinners were ranked around 250,000, and three editions of Woolman’s Journal were ranked in the top 100,000 items, with one at 52,845. Amazon’s sales figures suggest that these editions are reaching readers, and at least some such texts seem to be having an impact. A recent profile of New Calvinist minister Mark Driscoll in the New York Times Magazine reported that “paperback reprints of old Puritan treatises in the corner of a local bookstore piqued [Driscoll’s] interest in Reformation theology.”

Scholars of early America have long drawn on religious publications for our work; before online digital collections, religious presses’ facsimile reprints of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century texts were the most affordable and available editions of the texts we study. But we’ve generally not viewed pious readers as indicators of early American literature’s popularity, in part because religious editions often encourage readers to emulate their authors and adopt their beliefs. For example, John H. Gerstner’s introduction to Thomas Shepard’s Parable of the Ten Virgins exhorts:

Reader, beware! The Puritans are never “light” reading. However, Edwards is relatively easy alongside Shepard in the Parable … This work is valuable in inverse proportion to its readability. Don’t read it! Study it; a few pages at a time; decipher it. Live with it. Die with it. It may not save you, but it will leave you in no doubt if you are saved and even less if you are not …

If you are a typical church member today, you will learn that you are not prepared for Christ’s coming. Shepard will do everything in human power to get you prepared. When you realize that you have never “closed with Christ,” you will spend the rest of your life seeking and praying that Christ will close with you!

If that’s not worth $29.95, I don’t know what is!

Gerstner offers the book as an aid to spiritual self-knowledge and perhaps even salvation. In our classrooms, we take a very different approach. I often find myself reassuring students that I have no interest in preparing them for Christ’s coming or even in advocating Puritanism, Quakerism, or Deism. And I discourage students who want to judge whose faith is truest, explaining that although we’re interested in how various religious beliefs shaped the texts we’re reading, we aren’t taking sides.

But such claims aren’t entirely honest. While I don’t ask students to assess whether Anne Bradstreet’s or Thomas Shepard’s beliefs are closer to their own, early Americanists do often have allegiances to authors and texts. Perry Miller’s essays on covenant theology and preparationist soteriology reveal impatience bordering on affront with these encroachments on pure Calvinism, perhaps surprising in a scholar who referred to himself as a “goddam atheist.” And in a 1986 lecture that influenced my approach to Puritan texts, when Janice Knight distinguished between the “Spiritual Brethren” and the “Intellectual Fathers” of Puritanism, she called the Spiritual Brethren “my guys.”

Such allegiances enliven and shape our scholarship and our teaching. My own entanglement in Puritan texts emerged from a sense of connection with Anne Hutchinson and from frustration with accounts that seemed to trivialize Hutchinson’s concerns by treating theological issues as secondary. Scholars of Quakerism seem more comfortable acknowledging links between their faith and their scholarship. In his introduction to The Tendering Presence: Essays on John Woolman (2003), Mike Heller praises the collected essays as models of “dispassionate research” by scholars whose “lives also are touched personally and spiritually by Woolman’s writings” (xi). The collection includes a section titled “Scholars Who Became Disciples,” and biographies of several contributors refer to their membership in the Society of Friends. Of course, not all scholars who work in Quaker studies are Friends, and not all Puritanists take sides. But many readers have strong personal responses to early American texts.

Jonathan Edwards, for example, grabs hold of some readers. While most people who learn that I’m an early Americanist assume that I work on The Scarlet Letter, every so often someone says instead, “Oh, Jonathan Edwards?” and then quotes with great relish from Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. My friend David even quoted Edwards at length in a lay sermon he delivered on Shabbat Shuvah, the Sabbath before Yom Kippur. When I asked him later why he had chosen to discuss Sinners—hardly an orthodox text in our fairly traditional synagogue—he explained that he had studied Edwards with Richard Slotkin at Wesleyan University. A former music major who now works in finance, David remembered several course texts favorably, including “Indian stuff,” sermons, Franklin’s Autobiography, and Melville. But he had returned only to Edwards’s sermon, not as the Christian reader envisioned by Protestant presses, but as an observant Jew who rejects many of Edwards’s fundamental assumptions. While David’s sermon challenged Edwards’s view of repentance, reading Sinners nevertheless made a meaningful connection for him. David found Edwards’s visceral appeal and sense of immediacy relevant to his own community; they spoke to his sense “that not everything is optional, and that the synagogue is not the time to take the academic view of God and religion. Particularly, shabbat shuvah is a good time for a ‘spider over the pit of hell’ kind of speech. I was less discussing him [than] I was adopting his view of the world.” While this explanation surprised me, I suspect that many of our students make similar connections as they wrestle with early American texts and that the texts affect readers in ways we don’t anticipate.

Susanna Rowson’s novel Charlotte Temple has provoked intense responses from surprisingly diverse readers since its 1791 publication. Published in more than two hundred editions, Rowson’s novel is, in Cathy Davidson’s words, “one of America’s … all-time bestsellers” (159). Rowson specifically addresses young women (“Oh my dear girls—for to such only am I writing”), but her readers have included aggressively masculine men as well (29). One such reader was Reverend C. H. Covell, a sailor-turned-minister who placed Charlotte Temple at the center of his narrative of sea adventure and spiritual transformation. Indeed, the surprising account that appeared in the March 1906 Springfield Republican claimed that Covell “really owes his life to the book.”

In 1844, having deserted a whaling ship commanded by an abusive captain, Covell found himself stranded at Port Ottoway in Patagonia. Several of his companions starved to death and another “lost his mind,” but fortunately Charlotte Temple intervened by catalyzing the conversion of another sea captain, William A. Brown, commander of the Peruvian. Captain Brown was “one of those harsh unfeeling men that were found in such large numbers in command at that time.” But finding Charlotte Temple among the “promiscuous” reading material on board, Captain Brown was transformed by it. As he read, “The two characters of Montraville and LaRue grew more and more detestable as they revealed themselves to his awakened conscience. He began to question himself: ‘What prevents me from being just as base and as treacherous as they are pictured to be? Why, there is nothing but a pardoning Savior. I am as bad as they are. I have ill-treated my crew, and driven them to suicide; lashed them in the rigging and flogged them upon their bare backs to gratify my violent temper.’” Inspired to pray, “Capt. Brown became a changed man from that time,” reforming both self and ship:

no longer profanity and abuse to be used by his officers upon the sailors, no unnecessary labor upon the Lord’s day, not even standing of mast-heads, which is considered one of the most essential duties on board a whale ship; prayer meetings in the cabin to which all the crew were invited, but none compelled (and here I want to say that the crew numbered 30 men), not a Christian aboard when they sailed from home, but before the close of the voyage 27 of that crew were living true and honest lives. This great change was begun and wrought by one man, who was led to see his condition by reading the story of “Charlotte Temple,” which turned his attention to the book of books for salvation.

Covell credits Charlotte Temple with twenty-eight sailor-converts, along with wondrous material success. For despite Brown’s resolution to do “no unnecessary work … on Sunday, … no lowering of boats even if whales were seen, … he carried into New London the largest cargo of sperm oil ever carried in the same length of time.”

Moreover, while sailing for home, the transformed Captain Brown experienced a recurring vision, seeing “men suffering” in the gulf of Penas “just as plainly as though they were standing before him.” After two days without food or sleep, Captain Brown described his visions to the worried first mate and confessed his fear that they would drive him “crazy.” First mate Howe proposed a detour to the bay, but Brown worried that the men would think he was “losing [his] mind, or … growing childish.” Howe nevertheless approached the crew and explained the captain’s predicament, and they responded “with one accord, … ‘Whatever the captain wants to do, do it. We are willing.’” At Port Ottoway, they found and rescued Covell’s party. Covell’s account concludes, “I have given the bare facts, without detail, of what took place in a man’s life, the beginning of which was reading of the story of ‘Charlotte Temple.’ Blessings on his memory. All names and descriptions are real, no fiction. I am one of the rescued.”

A century later, Rowson’s novel continues to move readers in surprising ways. One afternoon in 2005, a student entered my office and proclaimed dramatically, “Charlotte Temple saved me.” How, you may ask (as did I). My student replied that she had been shopping when an older man approached her. As she began to feel uneasy, the man asked for her phone number. And then, she explained, “I heard Susanna Rowson in my head saying, ‘be assured, it is now past the days of romance: no woman can be run away with contrary to her own inclination’” (29). She walked away, relieved and feeling that Rowson’s guidance remained timely and relevant two centuries after Charlotte Temple’s publication.

Charlotte Temple is also inscribed in the New York landscape, in the form of a grave marked “Charlotte Temple” in Trinity Churchyard (fig. 2). During the nineteenth century, the gravesite was the “Most Popular Spot in Trinity Churchyard,” with almost daily visitors “in good weather.” Who, if anyone, is actually buried there is unclear, as parish records were destroyed by fires in 1750 and 1776. Some accounts suggest that the stone marks the grave of Charlotte Stanley, a young woman seduced by Rowson’s cousin, who may have been the model for Charlotte Temple. According to this theory, “After Mrs. Rowson told her story and all the readers began to visit the grave, the arms of Stanley and the name were removed from the tomb and the name of Temple substituted.”

In 1897, Henry Tyler offered a more skeptical account, interpreting the empty rectangle on the stone as evidence “that a former inscription was effaced and cut out, or else that … a memorial plate of metal, [was] subsequently removed.” The fire of 1776 left Trinity Churchyard “a waste of ruins,” and gravestones were moved during the reconstruction of the church from 1839 to 1846. “Among the waifs and strays was the brownstone slab,” Tyler explained, rhetorically associating the gravestone itself with poor Charlotte. “The metal memorial tablet having been lost or stolen, … some workman, or perhaps some sentimentally inclined parishioner in charge of the work of restoration, conceived the idea of filling in the blank with the fiction-name of Charlotte Temple.” Tyler conceded that this theory was “but a conjecture,” and predicted that “‘Charlotte Temple’s grave’ [would] not cease to attract gentle footsteps along the winding path, and bid them pause for her memory’s sake.” Despite his skepticism, Tyler did not mock such pilgrims: “None need think their sympathy wasted; for alas! there were only too many Charlotte Temples in fact if there was not one who bore the name.”

When my students saw photos of the gravestone, they were fascinated and decided to visit. A New York City transit strike delayed their outing until July, when one student organized a post-graduation field trip. Without believing that this grave held poor (fictional) Charlotte’s actual remains, my students approached the grave with respect for whoever might be buried there and with a powerful sense of connection to generations of readers who have visited the site (fig. 3).

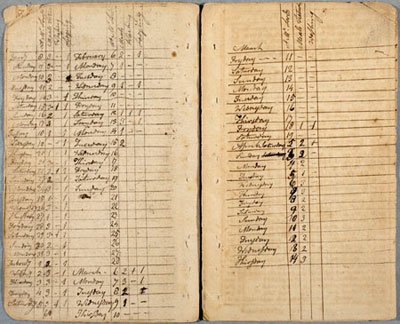

After visiting the Charlotte Temple grave, we explored the rest of the churchyard. At Alexander Hamilton’s grave, we found a woman who was taking photographs and strewing white rose petals (fig. 4). She announced that it was the anniversary of Hamilton’s 1804 duel with Aaron Burr. “Isn’t it sad?” she asked. As I had never actually grieved over the duel, I paused to consider her question.

She became impatient. “Do you know what happened? Don’t you know who he was?” she pressed. “Yes,” I replied and then asked what she was doing. She explained that she had learned about Hamilton in high school and had found his story so compelling that she has brought flowers to Hamilton’s grave annually ever since.

After we wandered away, my students asked me, “How could she ask if you knew who he was? Didn’t she know who you are?” I was touched by their exaggerated sense of my fame. (“Who do you think I am?” I asked gently.) And when they commented on the photographer’s eccentricity, I pointed out that we were the ones visiting the fake grave of a fictional character. Of course, my students were not misled by the name carved on the gravestone; they were fascinated by the way Charlotte Temple had engaged its readers and had come to be embodied in this physical site (and others—Tyler describes “at least three places in the city where it has been ‘always’ said that Charlotte Temple lived, or died”). Hamilton’s eccentric admirer offered an opportunity to reflect on the power of early American texts (and figures) to stir unexpected fascinations. Both in her case and in ours, the impulse to visit the churchyard reflected our sense that these eighteenth-century figures (whether real or fictional) were somehow connected to us.

Students’ connections to early American texts—whether to the spiritual message of Jonathan Edwards, the character of Charlotte Temple, or the generations of readers who have read the same texts—are often powerful and thought provoking. A few years ago, a student writing her senior thesis on Abigail Adams faced both personal and technological challenges, and emailed me to request an extension. Her subject line was “I ask myself: What would Abigail Adams do?” I asked her recently about this subject line and described the questions this special issue of Common-place would raise. While she acknowledged that “early American texts aren’t traditional beach reads,” especially since many readers think of “reading anything from even before the twentieth century . . . as hard work,” she insisted on the payoff: “But once one gets through that difficult layer of establishing how the language flows” and how to interpret “all the structural stuff of period literature—I think the opinions and beliefs and experiences that can be understood from the early American texts become … some of the most unique, special, intimate content for someone like me, at my age, as an American, to be engaged with. It’s just most of us are too lazy to approach that first layer!”

My student’s use of the word “intimate” struck me as apt. The readers I’ve discussed here—Reverend Driscoll, my friend David, Captain Brown, my students, even Alexander Hamilton’s flower-strewing admirer—all experienced intimate connections with early American texts. And having connected with these texts, these readers stepped back to reflect on the implications of those connections for their lives and for their understandings of the world.

Part of me still wants to see early American literature occupying the space of David McCullough’s John Adams—the best-seller list, HBO, the Golden Globes, and the carry-on bags of American travelers. I’d like to see the books I love to read and teach more widely enjoyed, even by those to whom they have not been assigned. I want them to be read not only with pleasure but also forpleasure.

But it’s more important to me that early American texts find readers like those I’ve described. Because beyond the pleasures early American texts offer, I also believe that they offer rich and complex understandings of American culture, politics, media, and religion. I want readers to feel connected to these writers and these texts—even as I understand that their connections may be on different terms than mine. But I also hope that they will reflect on those connections, that they will be provoked to think about parallels and distinctions between early America and the present, and that they will be inspired to learn more.

In short, I’d like to receive more emails like the one sent by former student Risa Garza last fall. Risa commented on the connection she perceived between the thesis she’d submitted the previous year and the 2008 presidential election. “On a side note, Governor Palin makes my need to return to Phillis Wheatley even more urgent. Seems like Palin would break the glass ceiling while crushing women’s lib underfoot; it’s really quite an accomplishment.” I was delighted by Risa’s sense that poetry and politics, Wheatley and Palin, political frustration and scholarly work are all connected. Who needs a Golden Globe?

Further Reading:

John Gerstner’s exhortation is found in his introduction to Thomas Shepard’s The Parable of the Ten Virgins Opened and Applied (1660; reprint London, 1695; reprint Boston, 1852; reprint Ligonier, Pa., 1990): 3-4. Molly Worthen describes Mark Driscoll’s reading in “Who Would Jesus Smack Down?” New York Times Magazine (January 6, 2009).

The Oxford University Press edition (1986) of Charlotte Temple (first published in 1791 as Charlotte, a Tale of Truth) includes an introduction by Cathy N. Davidson. Davidson discusses Charlotte Temple’s publication history in “The Life and Times of Charlotte Temple,” in Cathy N. Davidson, ed., Reading in America: Literature & Social History (Baltimore, 1989): 157-179.

Reverend Covell’s story appeared under the title “Advertising ‘Charlotte Temple’: A True Story of Religious Conversion and Its Mysterious Leading,” in the Springfield Republican 3:13 (March 29, 1906): 13. Accounts of the Charlotte Temple gravestone were printed and reprinted in various magazines and newspapers. Henry Tyler’s investigation of the gravesite, for example, was published in Leslie’s Weekly, then reprinted in the Springfield Republican as “A Shrine of Unhappy Love: Charlotte Temple’s Grave in Trinity Churchyard, New York,” Springfield Republican (November 13, 1897): 3. Speculations about Charlotte Stanley appear in A. b. D., “Who Was Charlotte Temple?” St. Louis Republic 85:22898 (February 19, 1893): 26, and A. b. D., “Charlotte Temple,” Philadelphia Inquirer 128:50 (February 19, 1893): 13. Other examples available through Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers include the following: “Died for Love, and Now, Her Grave is Always Covered with Flowers,” Birmingham Age Herald 21:45 (December 30, 1894): 2, reprinted from the New York Herald, and “Charlotte Temple’s Grave: The Most Popular Spot in Trinity Churchyard, New York,” Grand Forks Daily Herald 14:28 (December 2, 1894): 4. C. J. Hughes describes a December 2008 investigation of the gravesite in “Buried in the Churchyard: A Good Story, at Least” New York Times, December 12, 2008.

Thanks to Risa Garza, Libby Gery, David Marinoff, and Rebecca Rosen for permission to quote them and to Alisa Powers and Rebecca Rosen for permission to include photographs of them.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.3 (April, 2009).

Lisa M. Gordis is professor of English at Barnard College, where she teaches courses in English and American literature and American studies and directs the First-Year Seminar Program. She is the author of Opening Scripture: Bible Reading and Interpretive Authority in Puritan New England (2003) and is currently working on a study of early Quaker theories of language.

!["The Pocket Letter Writer." Color added title page from The Ladies' and Gentlemens' Letter-Writer and Guide to Polite Behaviour (Boston, [ca. 1860]). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/8.3.Henkin.1-182x300.jpg)

![Title page from The Ladies' and Gentlemens' Letter-Writer and Guide to Polite Behaviour (Boston, [ca. 1860]). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/8.3.Henkin.2-186x300.jpg)