Republicans and Abolitionists on the Road to “Jubilee”

It’s rare for a single work of scholarship to fundamentally change the way I teach a topic in U.S. history, but historian James Oakes’ latest work has done just that. Oakes has thoroughly persuaded me that the Republicans came into the Civil War ready to carry out much of the abolitionist agenda, meaning that they were willing from the beginning to destroy what Francis Lieber called the “poisonous root” of slavery. In his Lincoln Prize-winning book, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (2012), Oakes argues that as early as 1861, congressional Republicans, along with the president and his cabinet, and generals in the field, “insisted that slavery was the cause of the rebellion and emancipation an appropriate and ultimately indispensable means of suppressing it.” The Republicans were moving in lock-step with the abolitionists. As one widely circulated 1861 antislavery petition declared, Congress needed to utilize its “war-power” to destroy the “system of chattel slavery,” which the author of the petition labeled as the “root and nourishment” of the Confederacy.

Until recently, I have followed the trajectory of most textbooks and covered the abolitionist movement from the publication of David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World in 1829 to John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry thirty years later. Over the course of several weeks, we examine a selection of broadsides, pamphlets, images, and letters that have been scanned by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the National Humanities Center and the Boston Public Library. We also discuss how these documents fit in with the PBS documentaries (Africans in America and The Abolitionists) that students watched and responded to online the night before.

After covering the attack on Fort Sumter, I left the abolitionists behind and focused on the Republican Party. The narrative I presented painted the Republicans as reluctant emancipators, a party that had neither the support nor the encouragement of most abolitionists. The trajectory of the war shifted only over the course of several years from a struggle for the restoration of the Union to a no-holds-barred war against human bondage.

I often ask my students whether they think the Confiscation Act would have been issued if hundreds of refugees had not shown up at Fortress Monroe weeks before. They often conclude that the slaves themselves were partly responsible for pushing the legislative agenda in Washington.

Oakes’ scholarship, however, has forced me to ask an obvious but important question: How did the abolitionists succeed in achieving their ultimate goal? In this, Oakes challenges historian Manisha Sinha’s argument that abolitionist precepts were not represented within the ranks of mainstream congressional Republicans and that President Abraham Lincoln “gave short shrift to the abolitionist agenda” in the early years of the war. Though Frederick Douglass was often frustrated with the Republican Party, Oakes argues that Lincoln and the Republicans were committed to achieving what Douglass called for in May 1861: put “an end to the savage and desolating war” being “waged by the slaveholders” by striking “down slavery itself.”

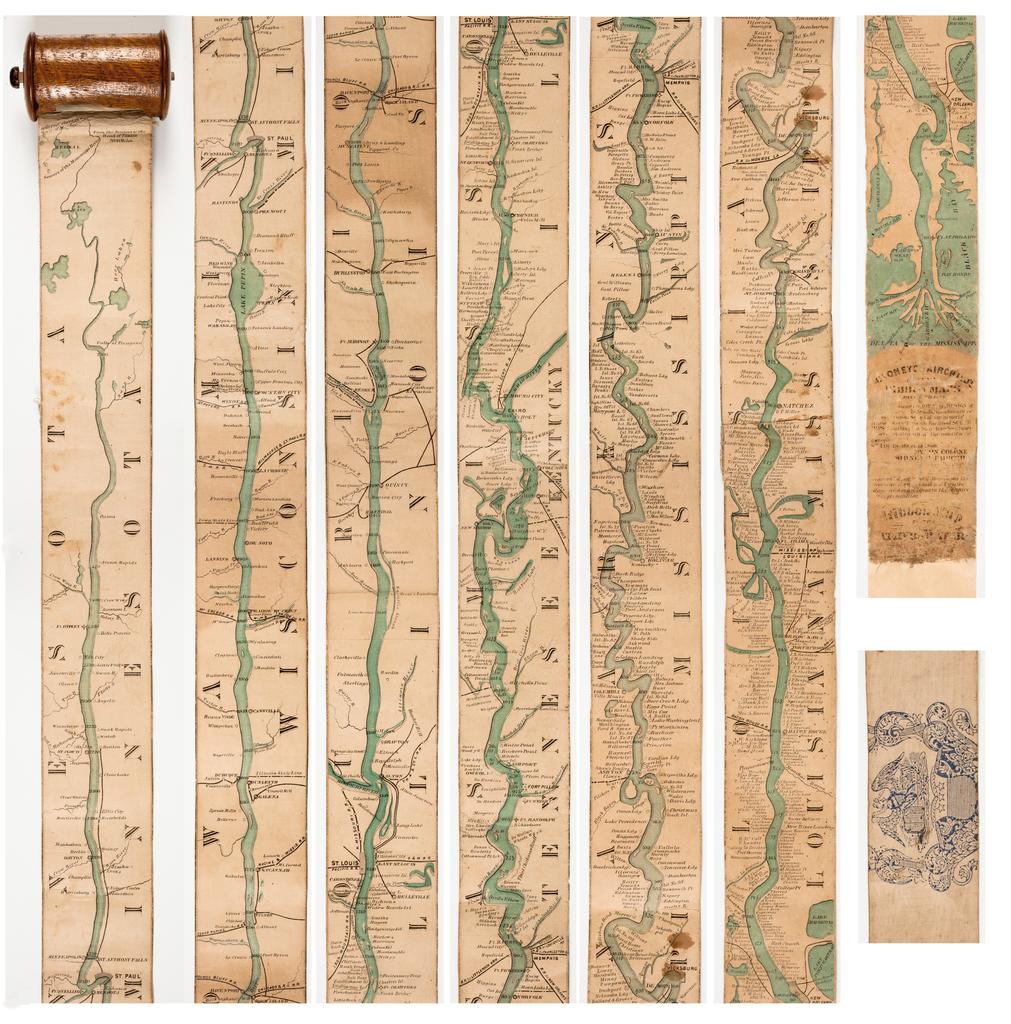

My students have responded enthusiastically to a multi-day lesson utilizing the Visualizing Emancipation Website. This ground-breaking digital history project allows students to map emancipation over the course of the war. Students view the unfolding of emancipation by tracking the movement of slaves toward the Union Army’s lines and the actions of soldiers and generals in the field. The Website can be used alongside the Freedmen and Southern Society Project and the Valley of the Shadow Project.

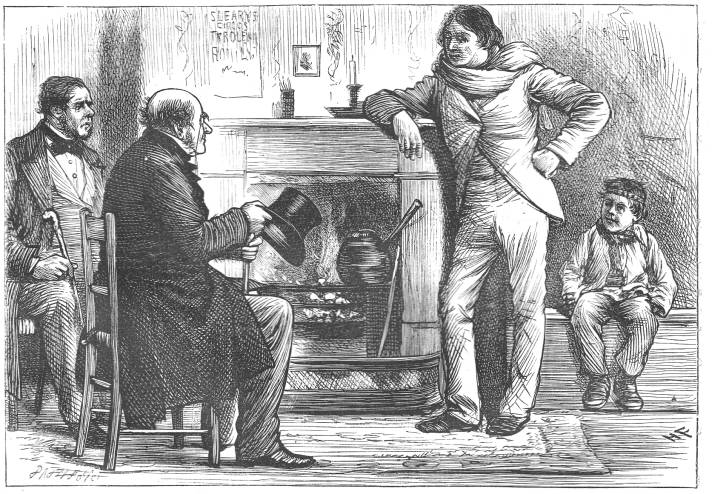

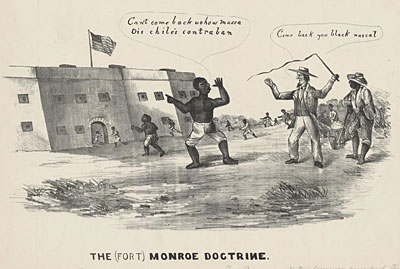

In the classroom, I use the students’ blog posts as a way to start a discussion. During their exploration of Visualizing Emancipation, many students picked up on the number of slaves that flooded Union lines in coastal Virginia not long after the firing on Fort Sumter. During the discussion we focused heavily on the role of General Benjamin Butler. On May 27, 1861, Butler, a conservative Democrat who opposed Stephen Douglas at the party’s 1860 convention, wrote to the Commander of the U.S. Armed Services General Winfield Scott asking him what he should do with the fugitives entering his lines at Fortress Monroe. “As a military question it would seem to be a measure of necessity to deprive their masters of their services … As a political question and a question of humanity can I receive the services of a Father and a Mother and not take the children?” asked Butler. “Of the humanitarian aspect I have no doubt.” What Butler needed was clarification on the political side of the equation. He decided to label the escaping bondmen “contrabands” under the rules of war and refused to turn them over. On May 30, Secretary of War Simon Cameron approved Butler’s decision not to return the “contrabands.” As Adam Goodheart has noted, slavery’s “iron curtain began falling all across the South.”

On August 8, 1861, two days after Lincoln signed the First Confiscation Act, which stated that Confederates who used slave labor to engage in rebellious acts would “forfeit” their claim to such “labor,” Secretary of War Simon Cameron issued instructions for slaves to be “discharged.” With his use of the word “discharged,” Cameron restored language used by Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull in an earlier version of Section 4 of the First Confiscation Act. Whereas Article 4, Section 2 of the 1787 Constitution prevented a “person held to labor or service” from being “discharged” if they escaped to a free state or territory, Trumbull’s amendment called for the military to emancipate or “discharge” enslaved people who reached Union lines. By treating the “contrabands” not as property, but as persons “held to labor,” the confiscation bill lined up with the long-standing view of antislavery Republicans. Cameron’s instructions also answered a question posed by Butler in a letter dated July 30, 1861: “Are these men, women, and children, slaves? Are they free?”

Lincoln never said a word in opposition to Cameron’s far-reaching order, which settled the status of those caught up under the terms of the First Confiscation Act on the side of freedom. There would be no further legal proceedings to debate the question. “Strictly speaking,” the act “freed only slaves used to support the rebellion,” writes Oakes. But “under the War Department’s instruction, all slaves voluntarily coming to Union lines from disloyal states were emancipated.” Indeed, in his December 1861 message to Congress, Lincoln used the word “liberated” when referring to slaves caught up under the provisions of the bill. I often ask my students whether they think the Confiscation Act would have been issued if hundreds of refugees had not shown up at Fortress Monroe weeks before. They often conclude that the slaves themselves were partly responsible for pushing the legislative agenda in Washington. As Steven Hahn has argued, black flight “began to reshape Union policy.”

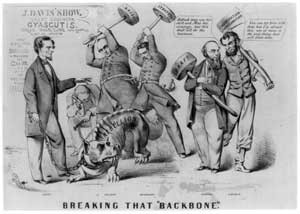

Oakes tackles the long-standing assumption that the “purpose of the war shifted” from one designed to protect the Union to one that promoted emancipation. This is the conventional narrative found in numerous textbooks or classics like Allan Nevins’ multi-volume Ordeal for the Union (1947-1970). Take, for example, the traditional rendering of Lincoln’s battle with General John Frémont in the summer of 1861 and General David Hunter in the spring of 1862. Historians have typically used the clash with Frémont and Hunter to demonstrate Lincoln’s reluctance to embrace emancipation. As Oakes noted in his 2007 book on Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, Lincoln merely ordered Frémont and Hunter to conform to the wording of Section 4 of the First Confiscation Act, which empowered officers to confiscate slaves that were being used against the Army or Navy, along with the subsequent War Department orders. Frémont had gone a step too far in his proclamation, emancipating slaves of all rebels in Missouri; Hunter declared the abolition of slavery in three entire states (South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida) not yet under Union control. Allan Nevins actually called Frémont’s order the first act for emancipation, ignoring the role of General Butler and Secretary of War Cameron.

Frémont and Hunter, in Lincoln’s analysis, had turned themselves into dictators. Lincoln told his friend Orville Browning on September 22, 1861, that he could not allow “this reckless position” to stand. Lincoln did not disagree with the agenda of freeing slaves; he simply wanted it done in a manner that followed what Congress had prescribed. In his order revoking Hunter’s emancipation edict, Lincoln reminded the public that he was still holding out hope that rebellious states would adopt a “gradual” emancipation plan. As Oakes noted in his book on Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, the president wanted to make clear that he was being pushed by the actions of slaveholders; they were the ones who “lit the fuse.” The bomb exploded in 1862.

Virginia slaves continued to escape to freedom as the Army of the Potomac moved south in the spring of 1862. In mid-March, General Ambrose Burnside captured New Bern, North Carolina. Nearly 7,500 blacks from the eastern portions of the state quickly made their way to the city. As one slaveholder declared at the time, the idea of “the ‘faithful slave’ is about played out.” Burnside carried on the same policies Butler had enacted. According to Oakes, a “tacit alliance between escaping slaves and the Union army” was “created with the approval of officials in Washington.” In July 1862, Congress authorized the president to enlist black men. The Second Confiscation Act empowered the president to “employ … persons of African descent … for the suppression of the rebellion.” In November 1862, the prominent abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson took command of the First South Carolina Volunteers, a regiment composed of freed slaves. “No officer in this regiment now doubts that the key to the successful prosecution of this war lies in the unlimited employment of black troops,” wrote Higginson. “Instead of leaving their homes and families to fight, they are fighting for their homes and families, and they show the resolution and sagacity which a personal purpose gives.” One month later, Attorney General Edward Bates demolished Chief Justice Roger Taney’s racist ruling in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) and declared in an official opinion that African Americans were full citizens of the United States.

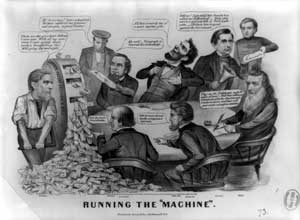

In addition to the Visualizing Emancipation Website, another exercise that allows students to explore the ideas James Oakes raises in Freedom Nationalis to search the text of the Congressional Globe. I found it useful this past term to have my students access the Globeonline, particularly the debate over the First Confiscation Act, via the Library of Congress’ Website. Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson declared: “Our purpose is to save this Government and to save this country … and if traitors use bondmen to destroy this country, the Government should at once convert those bondmen into men” so they could not “be used to destroy our country.” For Wilson, along with many of his colleagues, especially Senator Trumbull, freedom and the war effort went hand in hand.

By focusing on political history, Oakes reminds us of the astounding legislative record of the 37th Congress. Congressional leaders pushed through bills strengthening efforts to prohibit the international slave trade, granted diplomatic recognition to Haiti, and abolished slavery in Washington, D.C. On the military front, thousands of slaves sought refuge behind Union lines after the U.S. Army and Navy took control of the coastal regions of the Carolinas and portions of the Tennessee Valley.

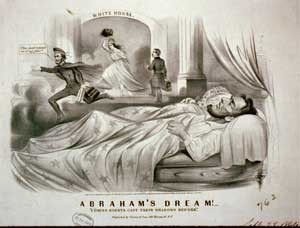

As “emancipation events,” to borrow a phrase from the editors of Visualizing Emancipation, became more prevalent, discussion of colonization also intensified. In the Second Confiscation Act, Congress attached an appropriation for voluntary emigration and authorized the president to implement it. Section 12 of the act reads: “The President of the United States is hereby authorized to make provision for the transportation, colonization, and settlement, in some tropical country beyond the limits of the United States.” In his second annual message to Congress in December 1862, Lincoln went so far as to call for a constitutional amendment authorizing funding for voluntary emigration.

For a long time, Lincoln held fast to the idea of voluntarily removing blacks, though there was only one tiny, privately organized experiment in voluntary exile. The businessman Bernard Kock asked Lincoln to help subsidize a project to send blacks to Île à Vache, a Caribbean island off of the coast of Haiti. Lincoln granted funding, signing off on the ill-conceived scheme on December 31, 1862. At this very moment Lincoln was also putting the finishing touches on the Emancipation Proclamation—something that my students often find shocking. Lincoln personally shut down the disastrous Île à Vache project within a year.

Michael Vorenberg’s research on colonization schemes during the Civil War has helped my students understand Lincoln’s writings concerning the removal of African Americans from the United States. I often use the September 1862 edition of Douglass’ Monthly to demonstrate the profound opposition to colonization within the black community. Douglass was responding to Lincoln’s August 14, 1862 disastrous meeting with a black delegation in Washington, D.C. The president urged the leaders to think about the possibility of mass emigration. “Taking advantage of his position and of the prevailing prejudice against them [African Americans] he affirms that their presence in the country is the real first cause of the war, and logically enough, if the premises were sound, assumes the necessity of their removal,” declared Douglass in response. However, as historian Kate Masur reminds us in a recent article, we need also to keep in mind that since so many “white Americans rejected the idea of a multiracial nation … many black Americans, recognizing the implications of that rejection, took steps to build their lives elsewhere.”

Another question history classes should explore is how mainstream abolitionists fit into this new narrative about the destruction of slavery that focuses heavily on the Republicans, a party of which many abolitionists were leery of trusting. I have found it useful to present my students with copies of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator from July 12, 1861 (accessed via the Early American Newspaper Project) in order to demonstrate the parallel tracks of Republican Party policy and abolitionist doctrine.

That edition recounts that on a warm and sunny July 4th afternoon in 1861 at Framingham, Massachusetts, a large town just west of Boston, more than 2,000 people gathered to listen to abolitionists lecture about the meaning of the war. In his inaugural address as the new president of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Edmund Quincy declared that there was never such an occasion as the one upon them to be “thankful.” The war had created a situation in which slavery could be destroyed. Quincy was greeted with laughter and applause when he told the crowd in Framingham: “The American Anti-Slavery Society has for its Office Agent—who? Abraham Lincoln … and it has for its General Agent in the field—General [Winfield] Scott.” Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase and Postmaster General Montgomery Blair had “not the heart nor the wish to put back into the hell of Virginia slavery one single contraband article in Fortress Monroe.”

During his turn at the podium, Garrison reminded the crowd that Lincoln’s cause was their cause. Both he and Lincoln would be given “a coat of tar and feathers” by the white South, proclaimed Garrison. The Boston editor went on to talk about how the war powers could be used to destroy slavery. The abolitionist editor had long given up on the notion that “moral suasion” could bring an end to the Slave Power. In 1837, he admitted to the British abolitionist Elizabeth Pease that American antislavery advocates were not making nor were they going to make an “impression” upon slaveholders. “I have relinquished the expectation that they [slaveholders] will ever, by mere moral suasion, consent to emancipate their victims. I believe that nothing but the exterminating judgment of heaven can shatter the chains of the slave.” That judgment arrived in 1861 in the form of Lincoln and congressional Republicans.

However, not everyone in the all-star line-up of speakers at Framingham had confidence in the Lincoln administration. Stephen Foster, for example, did not want abolitionists to commit to supporting Lincoln until an emancipation edict had been issued. In Foster’s analysis, the president was not up to the task. Foster declared that the administration was “undeniably the most thoroughly subservient to slavery of any which has disgraced the country.” In the eyes of Sallie Holley, a close friend of Foster’s wife, Abby, Lincoln was a “sinner at the head of a nation of sinners.”

The Fosters, along with the New Hampshire radical abolitionist Parker Pillsbury, quickly found themselves in the minority. For the Garrisonians, the war was going to bring revolutionary changes in the political system that could not be accomplished through moral suasion. Beginning in the summer of 1861, David Lee Child wrote a series of wide-ranging articles in The Liberator on the war powers. The “slave, once freed by the war power, would be free for ever,” declared Child, who drew heavily from an 1836 speech by the venerable John Quincy Adams.

A “defeat, bloody and cruel” was needed in order to “anger” the North into “emancipation,” said Wendell Phillips during his remarks at the Framingham rally. The prominent antislavery attorney and orator got his wish a few weeks later. On July 29, Child wrote to Garrison offering his view on the Battle of Bull Run. According to Child, the massive Union defeat had “done more than a dozen victories” in terms of convincing politicians that using the war powers was absolutely necessary. Former Rhode Island Congressman Elisha Potter Jr. agreed: “We may commence the war without meaning to interfere with slavery; but let us have one or two battles, and get our blood excited, and we shall not only not restore any more slaves, but shall proclaim freedom wherever we go.”

In early August 1861, Congress responded by passing the First Confiscation Act. A month later, Garrison, Phillips, and other Bay State abolitionists organized the Emancipation League, with the purpose being to educate the North on how central the issue of slavery was to the successful prosecution of the war. As historian Stacey Robertson has argued, the League “tried to stimulate abolitionist sentiment by insisting that emancipation would help the North to win the war.”

In January 1862, Garrison gave a number of addresses to huge crowds in Philadelphia and New York. Speaking about the origins of the bitter and bloody conflict the nation found itself embroiled in, Garrison proclaimed:

There is war because there was a Republican Party. There was a Republican Party because there was an Abolition Party. There was an Abolition Party because there was Slavery. Now, to charge the war upon Republicanism is merely to blame the lamb that stood in the brook. To charge it upon Abolitionism is merely to blame the sheep for being the lamb’s mother. But to charge it upon Slavery is to lay the crime flat at the door of the wolf, where it belongs. To end the trouble, kill the wolf. I belong to the party of wolf-killers.

Garrison, who was undoubtedly reveling in the applause from the crowds that came to hear him speak, crowds that would have likely pelted him with rotten apples (or worse) only a year before, also spoke about the war powers: “What the people have provided” to “save their Government, is not despotism.” It “is as much a Constitutional act, therefore, for the President of the United States, Gen. McClellan, or Congress, to declare Slavery at an end in our country.”

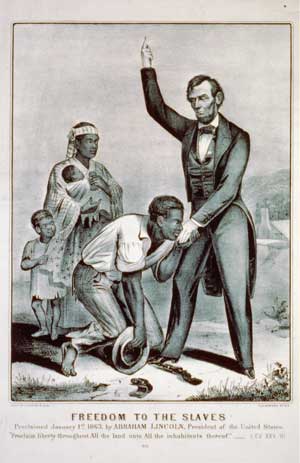

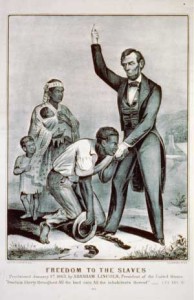

Lincoln made this a reality on January 1, 1863, when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Too often, teachers criticize the Proclamation because it is couched in legalistic, military language, lacking the moral force of a radical antislavery address. However, as Oakes rightly observes, “most Americans at the time associated military emancipation with antislavery radicalism.” Lincoln was moving in lockstep with antislavery constitutionalism. Even Stephen Foster, who never hid his hatred for Lincoln, argued that “emancipation proclaimed by the national government and enforced by the Army” would “effectively destroy the slave power.” Critics might speculate as to Lincoln’s motives, but one important fact remains: no slave was ever returned to bondage. The Emancipation Proclamation also encouraged the enlistment of black freemen. As historian Douglas Egerton has recently argued, black abolitionists “were as anxious to destroy slavery” as “they were to establish a bid for citizenship.”

Shortly after Lincoln was re-nominated at the 1864 Republican Party convention in Baltimore, Garrison traveled to Washington. “There is no mistake about it in regard to Mr. Lincoln’s desire” to “uproot slavery, and give fair play to the emancipated,” wrote Garrison to his wife, Helen. What helped to draw the prominent abolitionist editor even closer to Lincoln in 1864 was the administration’s abandonment of colonization. Abolitionists, according to Sallie Holley, had to work to “explode utterly all ideas of colonization as not only a cruel insult to the colored people, but a miserable national policy.” In this they succeeded. Lincoln made no mention of colonization in the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

In 1864, Garrison risked losing many of his devoted followers when he entered into a battle with his long-time friend Wendell Phillips, who was incensed over Lincoln’s announced reconstruction policy. As historian W. Caleb McDaniel argues in his engaging new book on democratic theory and slavery, Garrison—though unhappy about Lincoln’s unwillingness to commit to political rights for black Americans—still believed that the president deserved another term. In a September 1864 letter to Samuel May, in which he discussed the dangers of voting for John Frémont, the candidate of the Radical Democracy Party, Garrison declared that the “best thing” that the abolitionists could do is “join the mass of loyal men in sustaining Mr. Lincoln and thus save the country from the shame and calamity of a copperhead [Democratic] triumph.” Garrison was pleased with the Republican platform and its call for a constitutional amendment ending slavery. After the votes were tallied, Garrison, the man who had openly despised the American political system for decades, declared that Lincoln’s “re-election” was the “death-warrant of the whole slave system” and indicated that the country was “very near the day of jubilee.” In the final analysis, Republicans and abolitionists surely had their differences when it came to how slavery should be destroyed, but the historic significance lies not in what was different. What mattered most is what Republicans and abolitionists agreed on from the outset.

The author dedicates this article to Lawrenceville History Master Kristina Schulte.

Further Reading

Everyone interested in the destruction of American slavery should begin with Ira Berlin, Barbara Fields, Steven Miller, Joseph Reidy, Leslie Rowland, eds., Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (New York, 1993). The best overview of the abolitionist movement remains James Brewer Stewart’s Holy Warriors (New York, rev. 1996). Students of the 19th century have been waiting anxiously for Manisha Sinha’s forthcoming, The Slave’s Cause: Abolition and the Origins of America’s Interracial Democracy. In addition to Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York, 2013), see also Oakes’ The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York, 2007). Henry Mayer’s All on Fire (New York, 1998) remains the best biography of William Lloyd Garrison. No student of Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War can be without a copy of Eric Foner’s The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York, 2010). Silvana R. Siddali’s From Property to Person: Slavery and the Confiscation Acts, 1861-1862 (Baton Rouge, 2005) is a detailed treatment of these landmark pieces of legislation.Michael Vorenberg’s Final Freedom (New York, 2001) is the definitive account of the Thirteenth Amendment. Kate Masur’s An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill, 2010) details how the nation’s capital became a laboratory for Republican racial policy during and after the Civil War. Janette Thomas Greenwood’s First Fruits of Freedom (Chapel Hill, 2009) chronicles the creation of a network between Massachusetts and the eastern shore of North Carolina after Union troops from Worcester County took control of the area in 1862. For more on Garrison and Phillips in 1864 see W. Caleb McDaniel’s The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery (Baton Rouge, 2013). Douglas R. Egerton’s The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era (New York, 2014) brilliantly chronicles what Frederick Douglass meant when he argued in December 1863 that “the old Union, whose canonized bones we so quietly inurned under the shattered walls of [Fort] Sumter, can never come to life again … We are fighting for something incomparably better than the old Union.”

This article originally appeared in issue 14.3 (September, 2013).

Erik J. Chaput is a History Master at the Lawrenceville School, a college preparatory boarding school in New Jersey. He is the author of The People’s Martyr: Thomas Wilson Dorr and His 1842 Rhode Island Rebellion (2013) and the co-editor with Russell J. DeSimone of the Letters of Thomas Wilson Dorr and the Letters of John Brown Francis (forthcoming summer 2014), which can be found on the Dorr Rebellion Project Site hosted by Providence College.