Beyond Words: Sylvia’s Diary

I had no idea what I was getting into. I intended to take notes from one slender manuscript journal for a brief article or lecture. Yet somehow I’ve spent the last five years working with the thirty-year diary of Sylvia Lewis Tyler (1785-1851), an early nineteenth-century Everywoman, of Connecticut and Western Reserve Ohio. It’s a research journey that has unearthed artifacts made by, used by, or known to her, and it has taken me from Washington, D.C., to Connecticut and Ohio, stumbling down riverbanks and puttering through graveyards, using research tools and finding aids from vital records to dowsing rods.

I first learned of the diary when organizing a 2001 exhibition on childhood, for the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) Museum in Washington. I’d asked the archivist what the DAR’s Americana collection had that reflected teenagers’ activities in the pre-Victorian era. She suggested Sylvia’s diary, since it was begun at the age of fifteen, and chronicled the many chores and social activities of a Federal-era girl. I scarcely got a glimpse of the pages before the diary went into its exhibition case, but I did notice many references to spinning and sewing. Years later, I thought I’d take another look, hoping for some useful raw data on textile and clothing production in early nineteenth-century New England. I was taken aback when the archivist deposited nineteen manila folders before me, each containing a small, slim, hand-made volume.

I could have abandoned the project. I could have stuck to my original plan of just noting Sylvia’s textile and costume-related activities. I did begin cautiously, focusing on the spinning and knitting that appeared in nearly every entry. I also noted the names of neighbors and nearby towns, since the title page offered the only clue to where she lived: “Sylvia Lewis of Bristol.”

Working upstairs from one of the nation’s best genealogy libraries does help. Having once lived in the town adjacent to Bristol, Connecticut, I recognized some town names as Connecticut ones, but several states have Farmingtons and Hartfords. Just a few minutes spent checking some names in the diary against the 1800 Bristol, Connecticut, census confirmed my theory, establishing Sylvia as a Connecticut girl. A few more minutes with Bristol’s bicentennial history told me that another Bristol girl, Candace Roberts, had started a diary the same year. This was preserved at the Bristol Public Library’s Bristol History Room, and in another few minutes I was on the phone with Jay Manewitz, the librarian in charge of the collection. “Did you know there’s another Bristol teenager’s diary, begun the same year as Candace’s, and that she mentions Candace on the first page?” I tantalized him. “No! Is there a transcript?” he asked eagerly. “No,” I replied, and knew I was crazy to add, “I’m working on it.”

Thus I began to transcribe Sylvia’s diary, begun at age fifteen in 1801 and ending at age forty-six in 1831. (Two years are missing, and there is a gap between 1822 and 1828; the last volume covers 1829-1831 sporadically.) I could get through about three months of the tiny, sometimes smudged, often cramped, erratically spelled entries in a two-hour spurt: that was all I could stand, between eye strain and the archive’s frigid, artifact-friendly temperatures.

Why did I leap into this project—and why did I stick to it? Having spent four happy years in the town next to Sylvia’s Bristol, I have an abiding fondness for the area and interest in its local history. Moreover, Sylvia’s records are richly informative as social history. Since she was compulsive about chronicling her daily doings, I have assembled nearly twenty years of records for spinning, knitting, sewing, quilting, and laundry, and many entries on foodways, socializing, and other aspects of life in federal-era New England (and pioneer Ohio). From these entries, I’ve compiled “activity tallies”—charts and graphs of seasonal patterns in her various chores. (Was wash day always Monday, I wondered, as common understanding has it? Overwhelmingly, but not exclusively, yes.) Her mundane chronicles, over time, gave me a record of an entire community, and every bit of background and context I’ve found in my research has filled in the picture. I’ve found her entries, whether on textile production or fashion, socializing or foodways, travel or churchgoing, immensely useful in my study of the objects and people I research at the museum.

Most of all, Sylvia herself drew me in. Her occasional, restrained outbursts are endearing, from her distress at her father’s death to her raptures on reading her first Gothic novel. No surprise that she found The Children of the Abbey “the most entertaining book I ever read,” after the religious and moral tracts that formed her usual reading diet. Once I knew the cast of characters in the diary, the entries created a narrative, and I kept wanting to know what happens next. Would Sylvia marry Tracy Peck, who walked her home from a quilting? Or Abel Tyler, who nursed her through the spotted fever epidemic? Who would emigrate to Ohio next? Along the way, research became its own reward, and the challenge of finding more and more information to flesh out the spare entries of the diary became engrossing.

Five years later, I am still at it, nearing the end of the 1821 volume. I keep pausing for background research, and to take stock of Sylvia’s data. To go beyond the diary itself, however, I’ve embarked on a research journey that has drawn upon documents, artifacts, and field trips, in an effort to illuminate Sylvia’s written words and reconstruct her world and life.

My first research was biographical—to compile a “who’s who,” to understand who Sylvia was playing with, working for, and visiting. Sylvia’s father, Royce Lewis, was one of ten sons, most of whom grew to adulthood and lived near their father, Josiah, on what is still known as Lewis Street. I needed to sort out the relatives littering the diary. (Sylvia, not writing for an audience, seldom mentioned connections—but “Mrs. Hooker” would reveal herself as an aunt, for example, and Amy and Naomi as cousins as well as playmates.)

Gravestones were most helpful for my biographical summaries. I blessed New Englanders for their habit of inscribing “relict of Reuben,” “daughter of Eli,” etc., on gravestones, connecting children, parents, and spouses. I blessed Bristol’s Katherine Gaylord DAR Chapter, for having transcribed Bristol’s gravestones in the 1920s when they were still legible. Of course, some married daughters, and children who emigrated (whether to the next town or to New York or Ohio), weren’t included in the Bristol record; nonetheless, I had a pretty good Lewis family tree by the end of the first day’s digging, just in the DAR library. For other neighbors, family genealogy books at the DAR were helpful. Like the Lewises, there were often several related families of the same name, and it helped to know which branch of the Cowles or Ives family someone belonged to.

Casting my net a bit wider, I looked at vital records. Town vital records for Bristol are missing, but church records provided marriages and deaths. The Congregationalists’ baptismal habits frustrated me: only children of full members of the church were baptized, and not everyone believed in infant baptism (though Giles Hooker Cowles, Bristol’s pastor, published a treatise in favor of it). Thus, only the July 1805 death record for Sylvia’s niece Minerva, noting her age as 11 months, allows us to name the baby whose birth Sylvia reported in August of 1804.

Death records were often illuminating. Where Sylvia tended to note simply that “Mrs. Bartholomew” had died, the church clerk gave not only full names, but ages and causes of death. During the spotted fever epidemic that struck New England in 1808, Bristol fared better than some towns, but the emotional toll echoes through the clerk’s annotations: “May 3 Polly Wife of Luther Tuttle, aged 29 years Spottd fever Sick about four days very calm” reads a typical record. Sylvia, sick herself, afterwards wrote a day by day account, to the best of her recollection, of news she had heard during her illness. “I heard that Mr Luther Tuttle & his wife was very sick he says O my dear wife, she will die, what shall I do, she will go to heaven, he says—and at night she died and we trust sleep in Jesus,” she wrote for May 3. Luther died the next day. Read in tandem, the church death records and the diary portray a chilling two months in a small, interconnected community.

Despite abundant town and church records, I still found that Sylvia’s private notations were the only source for some biographical events, such as her brother Abraham’s two marriages and the death of his first wife. In October 1814, Sylvia recorded news of the death of “Abraham’s wife,” whose name she never once mentioned. No death record or gravestone survives in Trumbull County, Ohio, where Abraham and his wife had emigrated. And it’s only Sylvia who reported Abraham’s remarriage, on a trip home to Bristol in 1815, to the Widow Plumb. It takes piecing together several more entries’ clues, from 1801 to 1818, to reveal that Abraham’s first wife was Lois Lowry of Bristol and later Ohio. The Lowry family history confirms Abraham as Lois’s husband, but a newspaper obituary that recorded the death of “Mrs. Abraham Lewis” would put Lois’s death in 1837. Only Sylvia’s diary can explain that Lois died in 1814, and it is Rachel Plumb Lewis whose gravestone survives beside Abraham’s in the Vienna (Ohio) Center Cemetery.

Going beyond vital records, I hoped land records and maps would allow me to reconstruct a geography of Sylvia’s Bristol. This proved impossible. Did a single year go by without one or more Lewises buying or selling land, usually between brothers? I don’t believe so. I cursed, too, the New England metes and bounds system. Following English tradition, this method described plots of land as if the people involved were walking around its boundary, using natural and man-made landmarks, the old chains-and-rods measurements, and references to neighbors’ plots. After 200 years, not one of these landmarks or neighbors’ holdings survived, not even the location of the “highways” first laid out in the 1740s. How was I supposed to diagram land that began at a heap of stones at the southwest corner of Widow Cowles’s orchard?

Despite these obstacles, piecing clues from several sources has enabled me to pinpoint some places and people in the diary. For example, Sylvia wrote in 1812 of watching the cotton factory being “raised.” Chris Bailey, then curator of the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, had told me about Sylvia’s brother-in-law’s cotton factory, a relocated church building. But where had it been sited?

Fortunately for my quest, Bristol became a prosperous industrial town after Sylvia’s time and has been extremely well documented, starting with a church history by her old beau Tracy Peck. A 1907 history of the town stated that the cotton factory building had become part of the E. Ingraham clock factory, still in business in 1907. An 1896 map of Bristol showed me exactly where the Ingraham factory was: on a branch of the Pequabuck river that can no longer be seen, thanks to its diversion after a devastating 1955 flood. So there was the cotton factory: a half a mile or less from Sylvia’s house.

Being a curator and therefore object-oriented, I hoped to find some material culture related to Sylvia or her family. Sylvia had attended numerous balls at Uncle Abel Lewis’s tavern, and I knew that the Connecticut Historical Society (CHS) in Hartford had a large collection of tavern signs. Hundreds of towns, thousands of taverns—what were the chances Abel’s had survived? Then again—what if? I was astounded to learn that the CHS not only preserved Abel’s tavern sign, but also a flamboyant red and gold silk dress worn about 1825 by the adopted daughter of Abel’s son Miles and his wife Isabinda Peck. (Sylvia had quilted with “Binda” in 1803 and 1805.)

A few other artifacts have surfaced through my inquiries on genealogy message boards, which reached descendants eager to hear about Sylvia’s diary. Descendants of her daughter, Sylvia Tyler Bushnell, still have Sylvia’s family Bible, our source for her younger children’s names and dates of birth (born after the yearly volumes end), and for the name of her baby who died, age two days, in 1818. “Mr. Tyler held it when it Died which was about SunSet . . . my trials were new & not to be described to those who have not felt the same,” she heartbreakingly recorded in the diary, but with no mention of Susan’s name.

One descendant owns a skein of silk spun by Sylvia, a fantastic companion to a few diary entries in 1801-1802 in which Sylvia reported “pick[ing] silk balls” and spinning silk, and, more broadly, a rare artifact of Connecticut’s early attempts at sericulture. Two cousins treasure linen pillowcases possibly woven, but certainly embroidered, by Sylvia, dated 1828.

The third type of research I’ve conducted is geographical, and it’s been some of the most rewarding. Traveling to towns where Sylvia lived has allowed me to understand the layout of her communities and the distances between her and the neighbors and places she mentioned, and more subjectively, to get a “sense of place” for each locale she inhabited: Bristol before her marriage, nearby New Hartford, Connecticut, in 1809-1817, and the Western Reserve of Ohio from 1817 to her death in 1851.

Bristol was the obvious place to start. Jay Manewitz of the Bristol Public Library, who got me into this project, escorted me on my first visit, back in 2005, to Uncle Abel’s tavern (now an office). We stood in the probable ballroom, where Sylvia had danced at many a Thanksgiving and election-day ball, and then went to Cousin Miles Lewis’s house, now the Clock Museum. The current owners of Candace Roberts’s house, still a private home on the south side of town, welcomed us inside. Here, Sylvia and some other teens visited after church on March 1, 1801, and at least Sylvia and Candace decided to keep diaries, which both begin that same day. Finally, we saw the exterior of the houses of Uncles Roger and Eli, and across the street from them, the “Old North” or Lewis Street Cemetery, where so many Lewises are buried.

Cemeteries are addictive research libraries. I have returned often to both the Lewis Street and Down Street Cemeteries in Bristol. Making diagrams of the placement of Lewises in Lewis Street has shown how tightly knit this family was. In Down Street, I found the grave of Josiah’s first son, Roger, and also a small stone nearby inscribed only “d.L.”—probably David Lewis, the first of Josiah’s sons to die, aged only eight months, in 1752. I doubt anyone had thought to look for David in the tiny graveyard just south of the Pequabuck river, and I take not only a historian’s, but also a sentimental pleasure in finding Roger’s little brother, buried just “behind” him. I’m not sentimental about my own relatives’ graves—we are not a graveyard-visiting family—but locating the physical remains of these people I’ve come to “know” through the diary has been strangely compelling.

The grave I most wanted to find, of course, was Sylvia’s, in Ohio. I’d never have found it without help. The regent of the nearest DAR chapter put me in touch with an incredibly talented genealogist and DAR member, Sally Mazer, who enthusiastically embraced the Sylvia project, doing advance research and insisting I stay with her and her husband during my visit to Trumbull County. We also connected with Rebecca Rogers, a historian who’d published a history of Trumbull County’s wooden clock industry, in which Sylvia’s husband, Abel, and her brothers Abraham and Levi, all worked. Rebecca took us to the riverbank site of the old iron foundry outside of town, where Abel often went for clock parts, which Sylvia sometimes helped assemble. She also introduced us to Chris and Diane Klingemeyer, who shared their collection of Trumbull County clocks, and while none made by Sylvia’s family survive, it was a thrill to see examples made by her neighbors.

Sylvia’s grave was recorded in the Vienna Center Cemetery in the 1920s, but the gravestone had long since disappeared. Sally, however, knew of a 1900 map of the graveyard in the county’s genealogy library, and had narrowed down the area where Sylvia ought to be. As soon as I arrived in Ohio, Sally took me to Vienna (always, inexplicably, pronounced Vye-enna), to the cemetery next to the Presbyterian church in the center of town. There she opened her trunk to reveal her specialized graveyard research equipment: gallons of water, a trowel, scrub brushes, and the most unlikely finding aid I’d ever encountered: dowsing rods.

In addition to finding water, metal dowsing rods apparently will indicate the presence of a grave, by crossing into an X when you walk over one, holding the rods parallel before you. Even spookier, if you hold one rod perpendicular to the ground over a grave, it will move either clockwise or counter-clockwise depending on the sex of the body underneath. Unbelievably, this worked for me in a blind test. Having previously narrowed down the likely area, Sally dowsed for a grave where Sylvia ought to be, and in no time, her rods were magically crossing into an X. Gently using the trowel to pry aside the lawn, we found a flattened gravestone. Scrubbing off some mud and washing off the rest with the water, a name emerged: SYLVIA ….

Finding Sylvia’s final resting place was a highlight of my research journey, although the Ohio trip yielded more conventional research results as well. Back in Washington, I keep working on the diary, filling in gaps both useful and incidental. Sylvia’s life was not remarkable, in any traditional sense; she accomplished no notable feats, she has no prominent offspring. But she is nonetheless both memorable and historically informative—an Everywoman of her time and place, no longer anonymous. By recording her everyday activities and interactions with the people in her communities, she created a rich body of primary evidence that illuminates our understanding of early republican America.

In addition to finding water, metal dowsing rods apparently will indicate the presence of a grave, by crossing into an X when you walk over one, holding the rods parallel before you. Even spookier, if you hold one rod perpendicular to the ground over a grave, it will move either clockwise or counter-clockwise depending on the sex of the body underneath. Unbelievably, this worked for me in a blind test. Having previously narrowed down the likely area, Sally dowsed for a grave where Sylvia ought to be, and in no time, her rods were magically crossing into an X. Gently using the trowel to pry aside the lawn, we found a flattened gravestone. Scrubbing off some mud and was

Further reading:

Sylvia’s diary is unpublished, but transcripts are available to be shared with interested researchers. Sylvia’s diary informs Ann Buermann Wass’s study of Federal era clothing; see Ann Buermann Wass and Michelle Webb Fandrich, Clothing through American History: The Federal Era through Antebellum, 1786-1860 (Santa Barbara, 2010). The diary is also being used in a compilation of names of workers in the American wooden clock industry (ongoing), and by Walter Woodward in his forthcoming study of the Connecticut diaspora of the early nineteenth century. For background reading on some aspects of Sylvia’s life, Bristol’s most recent history is Bruce Clouette and Matthew Roth’s Bristol, Connecticut, a bicentennial history, 1785-1985 (Canaan, NH, 1984). Sylvia’s husband, brothers, and other clockmakers and peddlers mentioned in the diary are discussed in Rebecca M. Rogers’s comprehensive study, The Trumbull County Clock Industry, 1812-1835 (privately printed, n.d.).

This article originally appeared in issue 11.2 (January, 2011).

Alden O’Brien is the curator of costume, textiles, and toys at the DAR Museum in Washington, D.C. Her exhibits have included “The Stuff of Childhood: Artifacts and Attitudes 1750-1900,” “Costume Myths and Mysteries,” and “Something Old, Something New: Inventing the American Wedding.” She is currently working on “Fashioning the New Woman,” an exhibit on women and fashions of the Progressive Era.

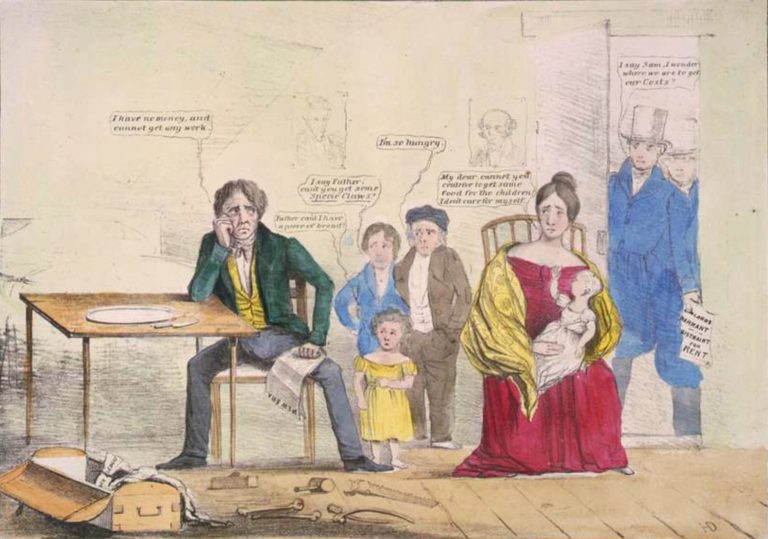

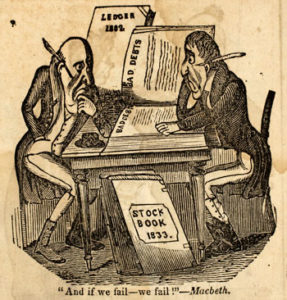

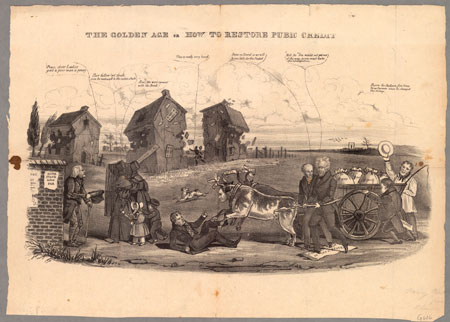

!["The Golden Age Or How To Restore Pubic [i.e. Public] Credit," lithograph (U.S., between 1832 and 1837?). Courtesy of the Political Cartoon Collection, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts. Click image to enlarge in a new window.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1-5-300x215.jpg)