A Bed Sheet in Beinecke

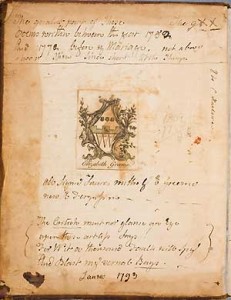

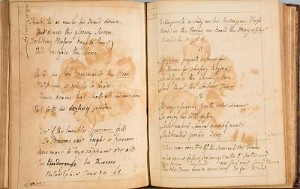

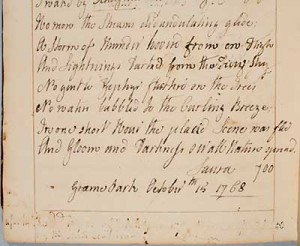

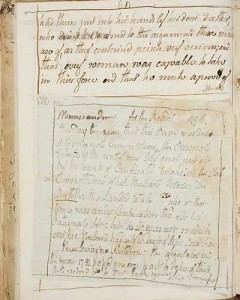

I had come to Yale to give a lecture, but since I had a few hours on my own I decided to check some references in the Beinecke Library, the university’s rare book and manuscript repository. I skimmed through the finding aid to the Jonathan Edwards Papers looking for the letters I wanted when I saw something unexpected listed for Folder 1655 Box 36. Confiding my astonishment to the woman at the desk, I called up the item. A few minutes later she took an acid-proof cardboard box from the library trolley, smiling as she placed it before me. I tenderly lifted the lid. There, cradled in tissue paper, was a handmade linen bed sheet folded to expose the blue cross-stitched letters TEE. A handwritten note sewn to the sheet explained: “This was spun by the Mother of President Edwards who was born in 1703 – It is probably now 155 years old – Nov 1846.”

I had seen lots of sheets like this in New England museums but I never expected to find one in a research library. I was tempted to unfold it to its full length just to see the reaction of the sober scholars seated at the polished tables around me. Instead I concentrated on deciphering the note, which I later discovered had been written by an Edwards descendant named Hannah Whittlesey. I found her note confusing until I figured out that “President Edwards,” not his mother, was the person born in 1703. (Jonathan Edwards had once been the head of the College of New Jersey, now Princeton, but the bed sheet didn’t belong to him but to his parents.) Like many antiquarians before and since, Whittlesey had used fixed landmarks to date an undatable artifact. Knowing that Esther Stoddard married Timothy Edwards in 1694, she concluded that the sheet was “probably” 155 years old in 1846. The date was a guess, but the initials left little doubt of ownership. The elevated E stood for Edwards, the T for Timothy and the E for Esther. The initials confirmed the attribution and gave it a place in the Edwards Papers when they came to Yale in 1900. Yet the sheet had nothing to do with the famous theologian. It had passed from Esther Edwards to her daughter Hannah Wetmore, from Wetmore to her daughter Lucy Whittlesey, and then from Whittlesey to her daughter Hannah, the writer of the note.

A year or so after my visit to Beinecke, I stumbled across another example of Hannah Whittlesey’s preservation work in the registration records of the Connecticut Historical Society. In 1840, she gave the Society a pair of silk shoes “worked by Miss Hannah Edwards daughter of Rev Timothy Edwards, of East Windsor, sister of President Edwards, and wife of Seth Wetmore, Esq of Middletown,” and a fragment of crewel embroidery “wrought by Miss Molly Edwards, daughter of Rev. Timothy Edwards.” Once again she identified the women who “worked” or “wrought” these items in relation to their presumably more distinguished male relatives. At the same time she memorialized their handiwork, claiming that the Edwards sisters had not only spun the thread in their embroidery but had dyed it “with the juice expressed from native plants.” Esther Edwards may or may not have spun the thread in her bed sheet, but her daughters could not have produced the thread in their fancy embroideries. To Hannah Whittlesey, however, there was no distinction between plain linen and high-style crewel. Everything surviving from the colonial period had to have been the product of a woman’s hands.

The embroideries in Hartford, like the bed sheet in Beinecke, exemplify the mythical power of New England’s age of homespun. Whittlesey was not alone in memorializing fabrics she thought had been spun by her ancestors. The image of the colonial dame toiling at her spinning wheel was widely cherished in the nineteenth century–much more so, in fact, than it had been during Esther Edwards’s lifetime. Between 1820 and the Civil War, New England novelists, poets, town historians, and creators of civic celebrations appropriated the spinning wheel as an icon of regional identity, laying the foundation for a complex and often conflicted approach to colonial women’s history.

Five years after Whittlesey labeled her great-grandmother’s bed sheet, the Hartford pastor and reformer Horace Bushnell told an audience at the Litchfield County, Connecticut centennial not to go into burying grounds looking for the monuments of famous men. “It is not the starred epitaphs of the Doctors of Divinity, the Generals, the Judges, the Honourables, the Governors, or even of the village notables called Esquires, that mark the springs of our successes and the sources of our distinctions. These are rather effects than causes; the spinning-wheels have done a great deal more than these.” For Bushnell, the spinning wheel symbolized all that was positive about the preindustrial New England economy–hard work, neighborliness, cooperation between husbands and wives, and patriotism.

By diminishing the public distinctions that Whittlesey cherished in her male ancestors, Bushnell made a place for ordinary people in history. But he also abandoned the individual identities–the succession of names, the embroidered initials, the silk shoes, and the crewel-embellished bed hangings that were part of her heritage. Neither he nor Whittlesey understood the ways in which household manufacturing, commerce, and gentility were entwined in the economy and culture of eighteenth-century New England. Looking back, all they could see was the spinning wheel.

They had illustrious company. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow introduced romance into the mythology of homespun in his 1858 poem “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” This was the story of how Plymouth Colony’s gruff military commander, Miles Standish, asked the handsome, young John Alden to act as a go-between in his courtship of the beautiful Priscilla Mullins and how she, in response, told John to speak for himself. In the climactic scene, Priscilla sits at her spinning wheel with “carded wool like a snow drift/ Piled at her knee.” Longfellow’s legend was so popular that an illustrated guide to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 assumed that a spinning wheel displayed in the “New England Log Cabin” was the “very one which Priscilla, the Puritan maiden, whirled so deftly that poor John Alden could find no way out of the web she wove about him.” By 1885, thrifty collectors could buy plaster casts of John Roger’s sculpture of the famous couple with the immortal words inscribed on the base, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John.” A Boston furniture manufacturer borrowed lines from the poem in an advertisement for parlor chairs made out of the discarded parts of old flax wheels. By the time of the Columbian Tercentenary, Longfellow’s story was so firmly planted in American history that John Alden and Priscilla Mullins appeared in a New York City parade alongside Columbus and Isabella.

The spinning wheel was as deeply entrenched in the American imagination as the Liberty Bell. Spinning entranced academic painters like Thomas Eakins as well as popular writers like Louisa May Alcott, who in Silver Pitchers, published in 1888, imagined a modern-day John beguiled by a costumed spinner at the Philadelphia centennial. Antique wheels salvaged from grandmothers’ attics appeared in undergraduate sitting rooms at Yale, in the mansion of a Montana mining magnate, and in hundreds of civic parades. Jane Addams organized spinning demonstrations at Hull House in Chicago and the Daughters of the American Revolution planted a stylized flax wheel on their insignia.

European institutions boast dazzling textiles left by nobles and the rich, but they offer very little to document ordinary clothing or homemade bedding and linen. New Englanders, in contrast, saved fabrics so humbly homemade that under magnification bits of unprocessed flax still cling to the thread.

The spinning wheel was an attractive emblem because it was so malleable. For patriots it symbolized women’s contributions to the American Revolution, while for sentimentalists it conjured up a timeless domesticity. Craft revivalists saw in it the harmony of labor and art, feminists women’s untapped productive power, and antimodernists the virtues of a bygone age. For Elizabeth Barney Buel, the wheel captured all of these ideals, and more. In The Tale of the Spinning-Wheel, published in Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1903, she attributed the success of the colonial experiment to female industry. “The plough and the axe are not more symbolic of the winning of this country from the wilderness, nor the musket of the winning of its freedom, than is the spinning-wheel in woman’s hands the symbol of both,” she wrote. Colonial wives “spun into thread and yarn the flax and wool that was raised on the farm, and then knitted every pair of stockings and mittens, wove every inch of linen and woolen cloth, and cut and made every stitch of clothing worn by a family which generally numbered ten or a dozen Johns and Hezekiahs and Josiahs and Hepzibahs and Mehitable Anns. No wonder a man could go to the war for his country’s independence, when he left Independence herself at home in the person of his wife.” Although she did not claim to be a feminist, her prose radiated a conviction that women mattered in the past, and that they had not been given their due.

For Buel, the spinning wheel united women across space and time. She laid out her evidence point by point, dropping learned allusions to archaeology, art history, folklore, mythology, opera, and the Bible. “No written page of history, no musty parchment or sculptured stone, is so old that we cannot find upon it some traces of the spindle and distaff with their tale of joys and sorrows spun into the thread by the fingers of patient women whose hearts beat as our own to-day, in tune with the common throb of humanity.” New York artist and Litchfield summer resident Emily Noyes Vanderpoel added authority to the argument with delicate drawings of mummy cloth, Stone Age fishing nets, and medieval distaffs as well as colonial flax wheels. Her frontispiece for the book captures Buel’s notion of a “woman’s sphere” centered in the home. A youthful spinner, dressed in the gauzy costume of the early republic stands in a vine-covered doorway, looking outward but securely planted within. Her enormous wheel, with its hub centered just beneath her slender waist, measures the reach of her arms and the power of her sexuality. She is both productive and potentially reproductive, fitted to her setting yet visible beyond it. “And the home still centres in the woman; the country still centres in the home, and no mere change of womanly occupation can alter God’s fundamental law of human society,” Buel wrote.

Suffragists among Buel’s contemporaries developed a more dynamic sense of women’s place in history without abandoning the wheel. In 1889, the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association mounted a historical pageant in Boston that surveyed women’s history from the landing of the Pilgrims to the present. Organized as a series of “living, moving, speaking tableaux,” it opened with Priscilla Mullins at her wheel, and then moved on to the banishment of Anne Hutchinson in 1638, the hanging of witches, and Hannah Duston’s scalping of Indians in 1692. After a “Home Scene in the Life of Abigail and John Adams” and a demonstration of the minuet, a woman dressed as the Goddess of Liberty watched suffragist orator Mary Livermore read the Declaration of Independence. The nineteenth-century tableaux featured “Garrison printing the Liberator,” followed by a portrayal of a “Women’s Anti-Slavery Meeting Broken Up by [the] Mayor of Boston.” A depiction of the relief work of the Women’s Sanitary Commission during the Civil War preceded Frederick Douglass’s reading of the Emancipation Proclamation. Finally, in the last scene, contemporary female writers and reformers portrayed themselves in “Woman’s Sphere, 1889.”

Where Buel used the spinning wheel to circumscribe a female sphere, the suffragist leaders of the 1889 Historical Pageant integrated it into an explicitly feminist history. In such a context, Priscilla Mullin’s choice of John Alden over Miles Standish represented the ascendancy of youth over age, love over power, New World freedom of choice over Old World convenience. “Was there a spice of feminine coquetry in her famous speech to John Alden?” one writer asked. “Or was it that she understood the dignity and worth of womanhood, and was the first in this new land to take her stand upon it?” For more than a decade, The Woman’s Journal had been criticizing male-centered ceremonials. The men who gathered to celebrate “Forefather’s Day” in April of 1879, wrote a New York correspondent, had forgotten the brave wives of Plymouth colony in a festival limited to male descendants of the Pilgrims. “Only as a sideshow was a handful of well-dressed ladies permitted to look on, while men ate and drank and lauded their male ancestors’ virtues. Thus did ‘the sons of New England honor Forefathers’ Day,’ in the very name of the feast insulting the daughters of New England and the memory of their foremothers.” No festival that included Priscilla and her wheel would be guilty of such an affront.

By embracing Priscilla Alden the mythical colonial spinner, women had found a place, if a circumscribed one, in history. Even Charles Andrews, who had little to say about women in the text of his magisterial history of colonial America, acknowledged their presence by selecting as the frontispiece for his final volume a photograph of a reconstructed “New England Kitchen” from the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts.

All of which helps to explain why a bed sheet was among the Edwards family papers when they came to Yale University in 1900. The surprising thing is that it remained with them. For in the middle of the twentieth-century, the reputation of so-called “pots and pans” history fell as the fortunes of once-forgotten clerics like Jonathan Edwards rose. For those interested in “the New England mind,” it was the letters and sermons of the male Edwardses, not the productions of their wives and sisters, that mattered. Nor did the “new social history” of the 1960s and 1970s show any interest in homespun. Historical demographers and students of sexuality were intensely interested in what went on between bed sheets, but it is safe to say that none of them traveled to Beinecke to study one.

When historians did turn their attention to household production, it was primarily to debunk the colonial revival notion that early American families spun and wove most of their own bedding and clothing. In Good Wives, published in 1982, I explained that between 1670 and 1730 fewer than half of households in northern New England owned spinning wheels and that the few weavers in the region were male. I argued for a new icon for women’s history. “Spinning wheels are such intriguing and picturesque objects, so resonant with antiquity, that they tend to obscure rather than clarify the nature of female economic life, making home production the essential element in early American huswifery and the era of industrialization the period of crucial change.” By then, I knew that Priscilla Mullin’s spinning wheel was a figment of Longfellow’s imagination, that early Plymouth colonists were too busy building farms and cutting timber to engage in household manufacturing, and that even if they had wanted to produce cloth there was little flax or wool to work with. But it wasn’t just a concern for historical accuracy that caused me to question the symbolism of the wheel. I wanted to break apart the nineteenth-century notion of an unchanging and universal “woman’s sphere.”

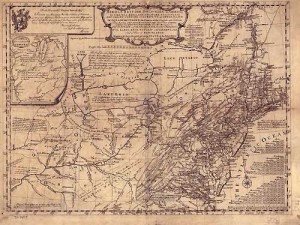

Nobody was more surprised than I when ten years later I began a serious study of New England’s age of homespun. My research for A Midwife’s Tale (published in 1990) told me that women in late eighteenth-century Maine were not only spinning but weaving, and that cloth making was at the center of a system of barter and exchange that I called a “female economy.” I wanted to know if the world of Martha Ballard was unique, or if similar things were happening elsewhere, and I wanted to know when and why women began to weave. So I began a massive study of household inventories that survive in large numbers for the entire colonial period. For my purposes, the key variable turned out to be the ratio of spinning wheels to looms. In commercial cloth making areas of England and the continent and in Pennsylvania, where continuous immigration perpetuated artisan weaving, there were eight to ten households with spinning wheels for every one with a loom. That makes sense, since spinning is more labor intensive than weaving, and it typically took several families to keep one weaver in work. In New England, however, the ratio of looms to wheels began to drop dramatically in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, until in some places there was one household with a loom for every two households with a wheel. The reason was simple. Weaving had become a part-time household task for women and girls. This dispersed system of manufacturing persisted into the nineteenth century, providing a base for an early putting-out system and eventually a labor force for New England’s famous mills.

This discovery turned everything upside down. Spinning wheels turned out to be markers, not of stasis, but of change. The key problem was not when hand production ended but how and why it began. Instead of the familiar evolution from subsistence to market production, I needed to understand how a highly commercial cloth making system in seventeenth-century England became the household production system Horace Bushnell and his contemporaries memorialized as “the age of homespun.” Suddenly, the collecting habits of the nineteenth century became important. If weaving was widely dispersed, then few weavers had much experience or training. What did their cloth look like? Did traditional fabrics change as women took over production? Those questions took me into museums and historical societies looking for surviving fabrics. I was amazed at what I found.

Motivated by a desire to include ordinary people–including women–in history, nineteenth-century antiquarians created what is arguably the world’s largest collection of ordinary household furnishings and fabrics from the preindustrial era. European institutions boast dazzling textiles left by nobles and the rich, but they offer very little to document ordinary clothing or homemade bedding and linen. New Englanders, in contrast, saved fabrics so humbly homemade that under magnification bits of unprocessed flax still cling to the thread. They saved ragged towels, warped bed blankets, cocoons left over from failed experiments in silk culture, and unfinished stockings still looped onto rusted needles. A curator at the Maine Historical Society in Portland recently opened an old trunk and found the bottom two-thirds of a woman’s linen shift with a penciled notation “old Linen for sore rags.” New Englanders saved weaving drafts written on the back of old letters, handmade dye books, and yarn reels carved in some farmer’s dooryard. They saved silk shoes, quilted petticoats, and crewel-work bed hangings, but they also saved stained and faded aprons and the ragged corners of old coverlets.

The artifacts nineteenth-century Americans saved open up many themes in early American social history. The bed sheet in Beinecke suggests two of them–the link between household production and gentility, and the centrality of textiles to the inheritance patterns of women. The initials on the bed sheet signify both themes. In the colonial era, embroidery was an elite accomplishment. The alphabets that embellished schoolgirl samplers signified both a girl’s literacy and her future role as keeper of household textiles, which before industrialization were far more valuable than furniture. Very few women had either the blue silk thread or the skill needed to produce cross-stitched initials like those on Esther Edwards’s sheet.

Objects marked with a woman’s maiden name or initials perpetuated female legacies in a society that gave married women little claim to property.

That a sheet marked in Edwards’s lifetime (if not at her wedding in 1694) survived to become a monument to the age of homespun tells us that the family was wealthy and continued to be so. In most households, sheets were used until they wore into rags and then were recycled into other uses. Those that survived their first owners were passed on to daughters, and if they lasted long enough and the daughters’ themselves had a surplus, might become genealogical relics. Like silver, these “relic sheets” were sometimes marked by more than one generation. Although this sheet bears the joined initials of a couple, probate inventories and other marked objects from the region (including the chests and cupboards that contained textiles) suggest that it was far more common to use the woman’s initials alone. Objects marked with a woman’s maiden name or initials perpetuated female legacies in a society that gave married women little claim to property. By the early nineteenth century a few women became quite bold in marking the bedding they produced. A particularly self-conscious inscription fills the center of a hand-woven coverlet made from factory spun cotton: “The Property of Abigail Bailey, Fletcher, Vermont.” To study household textiles, therefore, is to explore a little known arena for female expression.

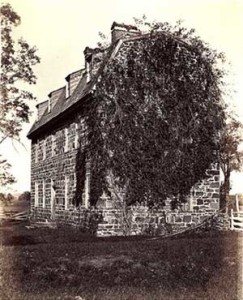

The silk shoes and the crewel panel at the Connecticut Historical Society enlarge the meaning of the bed sheet in the Beinecke. Hannah Whittlesey was wrong in her claim that the Edwards girls spun and dyed the thread in their fancy embroidery, but in a larger sense she was correct in attributing both common linen and ornamental fabrics to the “age of homespun.” New England’s female-centered production system developed in tandem with the aspiration to refinement. When Boston diarist Samuel Sewall visited Northampton, Massachusetts in 1716, he spent several hours with Solomon Stoddard at his parsonage, noting that old “Madam Stoddard, who is lame of the Sciatica . . . yet spins at the Linen-wheel.” Esther Stoddard was Esther Edwards’s mother. Like her descendants, Esther Stoddard was a woman of impeccable piety and genteel accomplishments. Her husband’s probate inventory, taken in 1731, listed both a spinning wheel and “Needle Wrought Cushions.” That combination was common among elite families from the late seventeenth-century through the Revolution. Large households not only had the raw materials and the labor necessary for household production, they had the need. They typically produced common linens, servants’ clothing, aprons, and blankets from their own flax and wool, but relied on imported cloth or artisan-produced fabrics for more refined uses. Esther Edwards–or her servants–might well have spun that linen sheet.

Household production spread beyond elite households in the early eighteenth century. By the eve of the Revolution, eighty to ninety percent of rural households owned spinning wheels, and almost half owned looms. As young men turned their energies to market production–herding, tanning, barrel making, cordwainery, lumbering, cabinetry, and other crafts based on the mixed agriculture, fishing, and timber–women increasingly devoted themselves to spinning and weaving fabrics for household use. As cloth production lost its craft status, it gained in mythic power.

The Revolutionary crisis and the struggle for economic independence during renewed conflict with England before the War of 1812 accentuated the political significance of household production, but neither conflict created the system that sustained it. For ordinary people, the production of cloth was never dissociated from a desire for refinement. Surviving fabrics, taken together with written documents, show the integration of homemade and store-bought fabrics in New England households from the late seventeenth century to the 1830s. The Henry Sheldon Museum in Middlebury, Vermont has an everyday shift, pieced and patched out of homemade linen by a skilled weaver who craved store-bought clothes and once confided in a letter to her son, “my father never bought me but one frock–and yours never but one–I have to worry thro’ thick and thin to get all my clothes, crockery chairs clock, and so on.” The fragmentary diaries and account books of Sarah Weeks Sheldon show that she clothed herself and children through a combination of household manufacturing and local exchange, trading handspun stockings for calico and butter for cloth. She was driven as much by a desire for middle-class refinements as by pure need. Unlike Molly and Hannah Edwards, the rural embroiderers of the early republic did spin and dye their own embroidery thread. Their productions were simple but their vision was clear. They wanted to be both producers and ladies.

The Revolutionary crisis and the struggle for economic independence during renewed conflict with England before the War of 1812 accentuated the political significance of household production, but neither conflict created the system that sustained it. For ordinary people, the production of cloth was never dissociated from a desire for refinement. Unlike Molly and Hannah Edwards, the rural embroiderers of the early republic did spin and dye their own embroidery thread. Their productions were simple but their vision was clear. They wanted to be both producers and ladies. Letters and diaries show the yearning for respectability that glossed even the homeliest of labor. The Henry Sheldon Museum in Middlebury, Vermont has an everyday shift, pieced and patched out of homemade linen by a skilled weaver who craved store-bought clothes and once confided in a letter to her son, “my father never bought me but one frock–and yours never but one–I have to worry thro’ thick and thin to get all my clothes, crockery chairs clock, and so on.” Sarah Sheldon’s diaries and accounts show that she clothed herself and children through a combination of household manufacturing and local exchange, trading handspun stockings and homemade cloth for calico and silk. Her spinning wheel was driven as much by a desire for middle-class refinements as by pure need.

Further Reading:

Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York, 1992); Horace Bushnell, The Age of Homespun, in Work and Play (London, 1864); Karal Ann Marling, George Washington Slept Here: Colonial Revivals and American Culture, 1876-1986 (Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1988); Kenneth P. Minkema, “Hannah and Her Sisters: Sisterhood, Courtship, and Marriage in the Edwards Family in the Early Eighteenth Century,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register 146 (January 1992): 35-56; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Wheels, Looms, and the Gender Division of Labor in Eighteenth-Century New England,” William & Mary Quarterly, 3d. Ser., 55 (1998): 37-38; The history of the Women’s Suffrage Pageant can be traced in The Woman’s Journal XIX (1888): 180; XX (1889): 100, 240, 276, 284, 292, 301, 316, 332, 416. More information on the Edwards Collection is available from from Yale University Library. Further information about The Age of Homespun can be found on the publisher’s Website.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.1 (October, 2001).

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich teaches history at Harvard University where she directs the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History. Her latest book, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth, will be published by Alfred A. Knopf in November 2001.

![Fig. 1. Sarah Franklin Bache. Engraving after John Hoppner [1791] (1863). Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/7.1.Davies.1-249x300.jpg)

The nasty, mendacious creativity of the present, cornered GOP really does seem to know no bounds. The near economic collapse that occurred on their watch, fostered by their ideology and their mismanagement, Republicans have decided

The nasty, mendacious creativity of the present, cornered GOP really does seem to know no bounds. The near economic collapse that occurred on their watch, fostered by their ideology and their mismanagement, Republicans have decided

So, to go historical for a second here, current Republicans apparently want to turn the Paulson bailout plan into the new “Tariff of Abominations,” a policy of theirs that they hope will reflect even worse on their opponents. The fabled Tariff of 1828 was a Democratic-originated bill that their hated enemy President John Quincy Adams signed into law. Adams was then furiously denounced for signing it in the ensuing campaign, which he lost, especially by tariff-hating southerners who had no choice (by their proslavery lights) but to keep supporting Democratic candidate Andrew Jackson whatever his northern allies had done. The

So, to go historical for a second here, current Republicans apparently want to turn the Paulson bailout plan into the new “Tariff of Abominations,” a policy of theirs that they hope will reflect even worse on their opponents. The fabled Tariff of 1828 was a Democratic-originated bill that their hated enemy President John Quincy Adams signed into law. Adams was then furiously denounced for signing it in the ensuing campaign, which he lost, especially by tariff-hating southerners who had no choice (by their proslavery lights) but to keep supporting Democratic candidate Andrew Jackson whatever his northern allies had done. The