The Tropical Turn

Los Angeles before the movies

In 1887, the writer Charles Dudley Warner, who had (with Mark Twain) named the late nineteenth century the Gilded Age, visited a booming Southern California and assessed its frenzied appeal. “If the present expectations of transferring half-frozen Eastern and Northern people there by the railway companies and land-owners are half realized,” Warner said, “Southern California, in its whole extent, will soon present the appearance of a mass-meeting, each individual fighting for a lot and for his perpendicular section of climate.” Warner’s projection (his sarcasm aside) was only the latest symptom of a regional identity that had been taking shape since the end of the Civil War—an identity whose characteristic images and themes would be magnified and multiplied through the twentieth century. That we do not readily recognize the nineteenth-century part of this story owes, in a word, to the movies—or, to the wholesale naturalization of the Gilded Age imagery of Los Angeles in the era of the classical Hollywood cinema and beyond—the era of, as it were, mass culture. So strong have the signs and signals of this era been, encompassing not only the movies but also literature, art, and architecture, that we have neglected an entire, earlier way of seeing Los Angeles—and “Southern California.”

But the nineteenth-century invention of Southern California deserves our attention. It resulted in the creation of a mythology and iconography that continues to surround Los Angeles, even as the early origins and full implications of this “L.A. style” continue to escape our notice. In the aftermath of the Civil War, “Southern California” meant something very different than it does today. To the extent that the name signified anything at all, it functioned negatively—a covering term for all that was not San Francisco, a city catapulted into the mental geography of the nation by the Gold Rush. This was a broad and indeed amorphous notion: Southern California as the territory stretching from Stockton in the north to San Diego in the south. When the author Charles Nordhoff wrote of it in his popular 1872 book, California, he meant Stockton (the city due east of San Francisco) and all points south. “Southern California,” he stated, “which includes the San Joaquin Valley and its extensions, . . . as well as the sea-coast counties parallel with these, is the real garden of the State.” Yet by 1890 things had changed, and Southern California as we know it today had emerged—a region centered on Los Angeles and perceived in all of those ways that have seemed, until now, to be the pure product of the twentieth century: of the movies and television, of artists like Ed Ruscha and critics like Reyner Banham. An entire prehistory to such developments lies back in the nineteenth century. Recovering a modest portion of this prehistory’s images and themes—and situating them in their own historical moment—is the purpose of this essay.

That prehistory begins in the turbulent—the industrializing, urbanizing, and diversifying—years after the Civil War, when Los Angeles’s promoters projected the idea that one’s senses rather than one’s mind would be stimulated in their small corner of the tropics, that prospects of things like palm trees would rid the body of the external as well as internal (the spatial as well as subjective) constraints of the Eastern metropolis, relieving the body of too much crowding and divesting the mind of too much thought. It was an idealized picture, leaving out all manner of contradiction and bespeaking the class as well as racial position of its authors, and it took shape against the backdrop of a major trend in the political economy of post-Civil War Los Angeles: the Anglo-American expropriation of Californio land (Californios being the Spanish-speaking people born in California prior to its U.S. annexation) and the subsequent subdivision of that land for commercial purposes. By the 1880s real estate had emerged as a distinct, dominant, and segregating economic sector, a development that coincided with the spread of increasingly visual technologies of communication, especially photography. The result was the onset of a speculative as well as spectatorial habit, a joining of “speculation” and “spectatorship” (both words derive from the Latin for “to see”), as the trade in land and the trade in images now began a peculiarly intimate association in the history of Los Angeles.

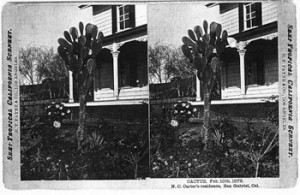

Consider first H. T. Payne, a photographer who displayed nearly one thousand views of Southern California in 1876 at the nation’s Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. In Payne’s views, collected in series like his “Semi-Tropical California,” equatorial plantings at the homes of leading citizens became agents in their own right—carriers of civilization in this latest imperial move westward. Palms and cacti draw the eye, mirroring the built forms of hearth and home and supplying the pictures with their very titles, as with Payne’s “CACTUS, Feb. 10th. 1876” (fig. 1). Here the subtitle names an early subdivider, N. C. Carter, who was developing the L.A. suburb of San Gabriel at the time. Viewed in isolation, the picture seems like an oddity, a strange testament to a lost era bound between tradition and modernity, the familiar and the exotic. But it was more than that: a first statement in a Southern California discourse that invited viewers to imagine their own tropical homesteads and to substitute their own names for N. C. Carter’s, as though transmitting their signatures upon the document (a contractual commitment was, after all, the characteristic goal of subdividers). In the flash of Payne’s camera, then, private property received a new and different look but one that already augured its own repetitive mass market—an early example of Southern California’s emerging tropical identity. Other examples included people themselves, as with Payne’s “Ladies in the Orange Grove” (fig. 2). A stately home presides over this improbable tableau, confirming the arrival of L.A.’s sun-splashed white newcomers in the final quarter of the nineteenth century.

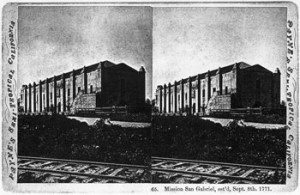

Such images gave no hint of the ugly colonial reality of nineteenth-century California, even if elsewhere Payne acknowledged L.A.’s shabby frontier appearance (see, for example, fig. 3). Ultimately Payne came no closer to the truth than to offer picturesque renditions of the region’s Catholic missions, established by Spanish friars in the late eighteenth century. His stereograph, “Mission San Gabriel,” was one such illustration, setting the monument within a frame of appealing decay (fig. 4). The depicted property was the origin of where, one hundred years later, N. C. Carter’s home would stand (as in fig. l), and where Carter himself would subdivide land as part of the entire area’s then quickening real estate nexus. Significantly, in the image of the San Gabriel Mission, Payne included the date of founding: “est’d, Sept. 8th. 1771,” which reminded the late nineteenth-century viewer that American history had a Pacific, not just Atlantic, component. In this telling, New Spain was to be seen as an ancestral ground prepared by the missionaries while America had carried out a revolution against Britain in the name of freedom. The missionaries, in turn, were to be seen as the progenitors of California landscape design—they had, after all, been the first to bring the palm tree, that most emblematic of tropical plants, into the region. All of this meant that such abuses as the forcible employment of Native Americans on the missions earned no mention, and ignoring the state’s long history of conquest and violence, the varied images of Payne’s “Semi-Tropical California” file thus leapt from the Spanish American past to the Anglo American future with hardly a word for what had come in between—that other geopolitical formation, Mexico, against which recent and bloody battles had been fought. This, finally, made the Spaniards’ acts of transplantation seem like divine favor, garnering the sympathy of promoters such as Benjamin C. Truman, who, in 1874, wrote, “The Anglo-Saxon pioneer found here a pueblo, the site of which had been selected with that almost intuitive recognition of the fitness of locality which seemed to be characteristic of the founders of the early Spanish settlements in the Occident.” For Truman (who had, among other things, reported on the Civil War for the New York Times), the Spanish American missions were “objects of profound interest.”

Projecting the world of the missions as the Romantic precursor to post-Civil War California, H. T. Payne and other promoters were assembling the elements of a new tropical identity for Los Angeles, and in this they were not alone. Indeed, by 1876, a group of promoters had begun to coalesce and to do exactly the same. They cited, if they did not outright copy, each other’s work. They produced imagery not only of palm trees and other decorative plants but also of commoditized things, like citrus fruit. Invariably, too, they found themselves checking their own promotional momentum, as when Benjamin Truman wrote, “No enchanter’s wand summoned up these orange groves, these fruitful vines, these waving fields of grain. Hard work and plenty of it wrought the miracle of transforming grove and thicket into these productive acres.” “Hard work” on the one hand and a “miracle” on the other, Los Angeles mirrored itself—magical and ordinary, artificial and real, blessed and damned—a dialectic of promotion that suited this prototypical culture industry, invoking truth and falsity at once and ultimately extending such values to language itself, which seemed by turns capable and incapable of representing the place.

In 1877, a promoter from Kansas, James De Long, who had been inspired by Charles Nordhoff’s California(1872), published his own short account, Southern California. He told of having toured several citrus groves and vineyards in Los Angeles County, reminiscing that “for several days the beauty of those lovely places haunted me, and I had almost come to the conclusion that what I had seen was merely imagination, and that such sights could not be found in 34 degrees north latitude in the United States, and so to satisfy myself I paid another visit and was fully convinced of the reality.” Reassured, De Long nevertheless insisted that “neither pen, pencil nor painter can describe those lovely places. They must be seen to be appreciated.”

Ironically it was De Long himself who also warned of the dangers of promotional excess, flatly stating, “Thousands of families have been ruined by the inducements held out in the glowing descriptions in hired newspapers, prize essays and stereoscopic views, in the interest of land speculators.” Ruin or not, the conventionalized identity of tropical Los Angeles had emerged in the short span of time since De Long’s source of inspiration, Charles Nordhoff, had published his own book in 1872. And when, in 1878, the travel writer Benjamin F. Taylor wrote of visiting Los Angeles, he expressed nothing but disappointment over the failure of the actual landscape to meet his expectations. “My idea of an orange grove,” he sighed, “was of an orchard where the trees laden with golden fruit sprang up from a smooth, green turf ‘of broken emeralds,’ that invited you to sit down on the dapple of a shadow every few minutes and be happy; of trees with a tropic brightness of foliage that would dispose me to listen to such fowls as the bulbul and sing gay little canzonets in two parts.” Instead he found and gave notice: “When you feel like reposing in a well-weeded onion bed you can take lodgings in an orange grove.”

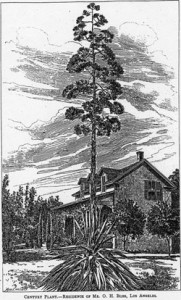

By the 1880s, the outline of the region’s promotional image was set. The publisher of an 1883 guidebook chose to include tropically themed pictures of the sort that others had first put into circulation in the prior decade. His “Century Plant.—Residence of Mr. O. H. Bliss, Los Angeles,” cast the region’s flora as actors in the drama of development—in the subdivision, purchase, and display of private property (fig. 5). “There is a strange mingling,” the guidebook explained, “of mountains and plains, hills and valleys, gardens and deserts; and their unusual and unexpected combinations are ever ready to interest the intelligent observer and to confuse the careless sight-seer. Climate and seasons are unlike anything known in the Eastern States. The weather may be said to ‘let one alone’ physically, but it is always exciting [one’s] wonder and study.” Other guidebooks expressed similar sentiments.

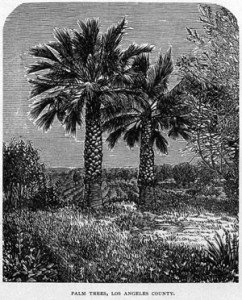

William R. Bentley’s Hand-book of the Pacific Coast (1884), which featured the illustration, “Palm Trees, Los Angeles County” (fig. 6), recommended that a visitor to Los Angeles find “one of the numerous bluffs surrounding the city” in order to take in the view, and in doing so Bentley was merely repeating visual instructions from the previous decade—Benjamin Truman in 1874 saying that “the denizen of Los Angeles, or the stranger within her gates, need only ascend the first eminence north of its business streets, to look out upon a scene which rivals in picturesque variety any vision which ever inspired the poet’s pen, or fascinated the beholder’s eye,” or another promoter, A. T. Hawley, writing in 1876 that “from almost every point of view a splendid panorama of mountain scenery greets the vision, while from the higher lands the view embraces the valley reaching to the ocean,” or James De Long reflecting on “the most beautiful horizon that can be imagined” in 1877.

All of these projections shared literally in the long view—the panoramic form as applied to what was, in truth, a relatively open and modestly settled location. Los Angeles was developing but not in the manner of the walking city (its suburbs emerged before its downtown). This meant, in turn, that vision could be uninterrupted, and promoters made sure that their readers (and viewers) knew this, different as it was from the frenzied visual experience of the “great cities” of the East. When the sociologist Georg Simmel addressed the latter in his seminal essay of 1905, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” he considered it a kind of sensory overload whose discontinuous cycle of rapid-fire “impressions” had trained up the “intellect,” which was necessary in order to safeguard the integrity of one’s inner self. By contrast, the image of tropical Los Angeles sidestepped all such incursions and requisite defenses. “All over this beautiful landscape,” Bentley’s Hand-book resumed, “are dark patches of orange, lemon and lime groves; palms, pepper, eucalyptus, . . . and a multitude of other plants, trees, and shrubs, that have, as if by magic, sprung into existence to adorn a scene beautiful beyond comparison.”

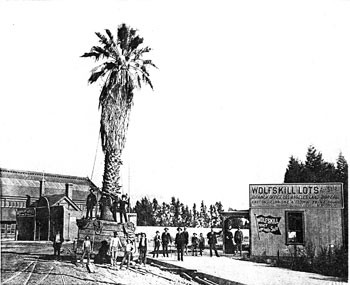

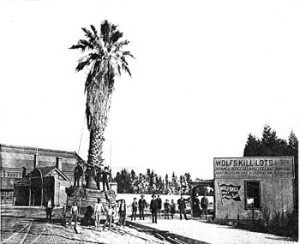

Here again was the dialectic of promotion: tropical Los Angeles had materialized “as if by magic,” but there was, in fact, evidence that reveled in displaying the artifice, as with one promotional photographer’s testament to the human labor and organization involved in transplanting such big plants as Bentley had catalogued (fig. 7). Such an image did not have to be marketed, but that it was marketed indicated a public appetite for it—a popular wish to assemble as well as disassemble such constructed landscapes. Meanwhile, Los Angeles was in the process of becoming an increasingly viewable place—the Atchison, Topeka, and Sante Fe Railroad Company determined, in 1884, to extend its rail lines to the city, leading to a rate war with the Southern Pacific and the onset of a land boom that put Los Angeles on the nineteenth-century map. As a result, more and more publishers of travel literature began to stock Los Angeles subjects.

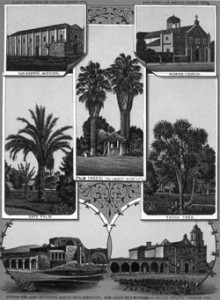

The Ohio-based company, Ward Brothers, which produced an entire catalogue of the period’s typical “souvenir” albums, began a series on L.A. Its 1886 edition featured palm trees in various settings, juxtaposed with the missions where the plants had originally been introduced (fig. 8) or depicted within the grounds where they had more recently been transplanted (fig. 9). Visitors too were arriving in greater numbers, among them a popular writer named Emma H. Adams, whose To and Fro In Southern California appeared in 1887. Adams proposed that “the apparent rapid flight of time” was a “singular feature of life” in the region. “How to account for this influence is difficult,” she admitted. “There seems to exist in the country a something which cheats the senses. Whether it be in the air, the sunshine, in the ocean breeze, or in all these combined, I can not [sic] say. Certainly the climate is not the home-made, common-sense article of the ante-Rocky Mountain States. It is a product of consummate art.” Here again tropical Los Angeles seemed both real and artificial. The weather cast “an unreality around life,” said Adams. “All alike walk and work in a dream.” This was, in short, a senseless landscape. By evening time, Adams insisted, “I find myself unspeakably tired, but have had no appreciation of the passage of the day. Had I been at home, on the southern shore of much maligned Lake Erie, I should have ‘sensed’ the going by of nine honest, substantial hours, though I had been just as busy.” In the accretion of moments like these, the double-sidedness (not to say double-talk) of L.A.’s promotion held out the empty truth, and still people wanted it. “Now,” Adams herself concluded, “I am not finding fault with this state of things. I rather like it. I think all the people do. It is in keeping with every thing [sic] else on this coast. Every thing [sic] is new and peculiar and wonderful.”

Such talk of climate and landscape drew the skepticism of Charles Dudley Warner, who had, again, visited Los Angeles in 1887 amidst the commotion of its railroad-to-real-estate boom. Invoking the Social Darwinian ideas of the time, Warner wrote, “One of the great uses of New England in the world is that of an object lesson, for the devotees of the development hypothesis, of the survival of the fittest.” But “Southern California,” he forthrightly declared, “offers to illustrate the converse.” For Warner, the mammoth migration of Americans animating the Los Angeles land boom constituted “both in quality and volume, the most striking phenomenon of modern times.” Yet, unlike the movement of people tied to the Gold Rush of 1849, the “present emigration is not for adventure at all, and primarily not for gold; it is a pursuit of climate.” It was, in other words, the consequence of a “human desire for dwelling in a place genial and tolerant of human physical weakness.” Warner was pointing to the much advertised healthfulness of the region—but this was the rub. Did not the promotion of a tropical Los Angeles ultimately underwrite the grandest paradox of them all—that a domesticated tropics should entail, in the very act of domestication, a migration of disease and mortality as terrible as anything that promoters and their audience took to characterize the tropics themselves? In this regard, the promotion had been fraught all along. Didn’t Warner now demonstrate the falseness of the commodity once more? As he dryly insisted, “the buyer, amid the myriad signs of ‘Real Estate for Sale,’ ought not to be confronted by so many legends of ‘Undertakers and Embalmers.’ It chills ardor.” In other words, deaths still occurred, despite the city’s happy promotion, and if the publicists of Los Angeles had wanted, they could have further boasted possession of the American West’s first crematorium.

Warner was fascinated by the place all the same. A few years later, in 1891, he published an entire book on Southern California. “It must be confessed,” he wrote at that time, “that there is a sort of monotony in the scenery as there is in the climate,” and he proceeded to judge that “the present occupiers have taken no hints from the natives. In village and country they have done all they can, in spite of the maguey and the cactus and the palm and the umbrella-tree and the live-oak and the riotous flowers and the thousand novel forms of vegetation, to give everything a prosaic look.” Warner did not like this look, but the promotional words and pictures of the previous two decades had projected it consistently, just as a picture presumably taken by the photographer Carleton E. Watkins, titled “Street View in Los Angeles” and published in William Seward Webb’s California and Alaska of 1890 (fig. 10), did nothing so much as evoke H. T. Payne’s earlier tropical take, “CACTUS, Feb. 10th. 1876.” Imitation or, as one guidebook put it in 1886, “emulation” had become the name of the game.

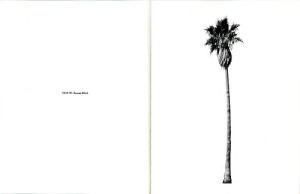

It was the ongoing predicament of tropical Los Angeles—and of a promotion already beginning in 1883, 1886, and 1890 to be exhausted by its own success. The movies, when they arrived, would simply give all of this second life, and in turn we would eventually receive the postmodern estrangements of an artist like Ed Ruscha, whose book of 1971, A Few Palm Trees, took the palm-planted landscape of Hollywood and made it seem unfamiliar once more. See, for example, figure 11, where (as in all of the book’s images) the city receives a literal whitewash, leaving only the trace of isolated palm trees behind and, opposite them, captions that disclose their true locations (in figure 11, the address is “5529 W. Sunset Blvd.”). What is this if not a late twentieth-century take on—and part of—a process begun a century earlier?

Can we, then, truly understand such comments as A Few Palm Trees, such period styles as the classical Hollywood cinema, or such symbolic formations as the twentieth-century “culture industry” itself without stopping to recall the likes of H. T. Payne, Benjamin Truman, and Emma H. Adams, or to review the words and images that they and others disseminated, or to remember their now forgotten views of late nineteenth-century Los Angeles? The answer, if we care to look, lies in the years before Hollywood—in the nineteenth not twentieth century—and in the still not moving pictures of a moment waiting to be seen anew.

Further Reading:

An early survey of the region’s social and cultural history is available in Carey McWilliams’s Southern California Country: An Island on the Land (New York, 1946). McWilliams’s narrative style shares much with that of Kevin Starr, whose Americans and the California Dream (New York, 1973) provides a particularly good introduction to the intellectual history of the state as a whole. David Wyatt masterfully traces what he calls The Fall into Eden: Landscape and Imagination in California (Cambridge and New York, 1986). A different, more workaday aspect of the garden motif is treated in John E. Baur’s The Health Seekers of Southern California, 1870-1900 (San Marino, Calif., 1959). Groundbreaking books in the scholarship of the region’s social history are Leonard Pitt’s The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846-1890 (Berkeley, Calif., 1966) and Richard Griswold del Castillo’s The Los Angeles Barrio, 1850-1890: A Social History (Berkeley, Calif., and London, 1979). Anders Stephanson discusses the entire era’s key expansionary dynamics in the middle chapters of his Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (New York, 1995). For the imperial nexus marking Los Angeles itself, see William Deverell’s state of the art Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of Its Mexican Past (Berkeley, Calif., 2004). The photography of the American West is authoritatively examined in Martha Sandweiss’s Print the Legend: Photography and the American West (New Haven, 2002). Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno’s “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” which appeared as part of their Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments (Amsterdam, 1947), was written (not coincidentally) from their home in exile: Los Angeles.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.4 (July, 2008).

James Kessenides is assistant professor of history at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. This essay grows out of his current project, a cultural history called Before Hollywood: A Prehistory of Los Angeles.

![Portrait, "R[alph] W[aldo] Emerson," mezzotint by John Sartain after Mrs. Hildreth, taken from The Drawing-Room Scrap Book (Philadelphia, 1850). Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.](https://commonplace.online/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/15.3-Beneke-4-222x300.jpg)